When one broaches the topic of “women in missions,” heroic icons like Mary Slessor, Amy Carmichael, Lottie Moon, and Helen Roseveare come immediately to mind. One does not form a picture of Jane Biles, an ordinary homemaker, who sensed a call to mission in 1699. In the book Wilt Thou Go On My Errand? author Margaret Hope Bacon recounts how Jane felt the Lord calling her to return to her native England as a Quaker missionary, but her husband William resisted the idea. Jane submitted to him, but her sense of calling persisted. She sought guidance from the General Meeting of the Ministry of Friends, which told her to pray about it. Months passed and her husband continued to resist. She eventually convinced him to go before the General Meeting with her and the board encouraged them both to wait “for further assurance of the mind of the Lord in it.”Jane waited another six months. When the board members met again, they grew convinced that her calling was legitimate and that William’s resistance was not, so they gave Jane their blessing to proceed. The next day, William agreed to “give up” Jane to her calling and decided, in fact, that he would join her. This decision seemed spur of the moment to board members, who told him to wait another six months. Jane waited with him. They finally set sail in 1701. The ship’s scribe recorded their passage in the log as that of “William Biles and his wife.”The story of Jane Biles captures the picture of women in missions today in several respects. First, she was an ordinary homemaker who heard a call. Second, she faced a culture of resistance that pulled her, like gravity, away from the sphere of missions service. Third, while honoring her husband, she did not give up and allowed God to pave the way for her to answer her God-given calling.If there has ever been an arm of evangelicalism where women have been given a wide berth to express their gifts, it has been the missionary arm. Many were cut from the cloth of the heroic “matriarchal” missionary pioneer (like Slessor or Carmichael) who paved the way for generations of like-minded female (and male) servants to answer a similar call. But the days of the heroic missions matriarch are over. The picture of missions is changing generally; no longer does an authoritative Western icon who introduces Western sensibilities to an indigenous context. The days of the heroic “patriarch” are similarly obsolete.Still, other forces are shaping the missions picture and, in some cases, are creating obstacles for women who hear the call. It isn’t that women are intentionally excluded as much as a blind spot in the largely male-run evangelical subculture. In other cases, missions are being redefined in a way that de facto squeezes women out of active service.Susan Perlman, associate executive director of Jews for Jesus and president of the board of the Interdenominational Foreign Mission Association of North America (IFMA), once asked Billy Graham, “If a woman feels the call to mission, is gifted for ministry and leadership and comes up against a solid wall of resistance, what advice would you give her?”He said, “If God is leading her, she shouldn’t take no for an answer.”Therein lies the good news in this otherwise troubling picture. Lots of women are refusing to take no for an answer. And where front doors are being shut, they are walking around to the back and finding another point of entry. As a result, the picture of missions is changing today, and those women who seek will find that the opportunities to serve have never offered more excitement or challenge.

Fueling the missionary movement

The so-called golden era of missions began in the early 1800s, and one could safely say that women drove it. They had the benefit of neither theological training nor even higher education, but female pioneers created a groundswell of missions energy that galvanized the modern missionary movement in its first hundred years.”Early nineteenth-century women. … wrote letters and kept journals that reveal a rich thought world and set of assumptions about women’s roles in the missionary task,” writes Boston University professor Dana Robert in her American Women in Mission (Mercer University Press, 1997). “The activities of missionary wives were not random: they were part of a mission strategy that gave women a particular role in the advancement of God’s kingdom.”Whether by nature or by default, women’s work focused on the tangible and relational aspects of the gospel message, what Robert calls the “social and charitable side of mission.” Women met physical needs, emphasized education, and innovated—taking on everything from medical ministries and Bible teaching to orphan relief, language studies, and literacy training. Women’s “close involvement in the daily lives of people” had two positive effects, says Robert. First, it “soften[ed] the effects of cultural imperialism” that tarnished much of the early missionary movement. Second, it created a model for gender-based missions (i.e., women ministering to women) for subsequent generations.By the late 19th century, more women than men filled the missionary ranks. Women began to develop an informal network that came to be known as the “women’s missionary movement.” This network helped develop over 45 women’s mission agencies (both independent and denominational) that promoted women’s missions, raised funds, and mobilized women to minister overseas to other women and their children. “Thousands of women were sent out from the women’s missionary movement,” says Calvin Seminary missiologist Ruth Tucker, “while millions on the home front supported that.”Reaching women stood at the center of the mandate. The women’s missionary movement was “a gender-separatist movement that was concerned about women and children and analyzed how to reach them,” says Robert. It followed the model of the Woman’s Union Missionary Society, a multidenominational organization established in 1861 that appointed single women to go to “heathen lands” and specialize in outreach to women.From all this arose a score of heroic figures who have remained missions icons. Amy Carmichael heard the words “Go ye—to those dying in the dark—50,000 of them every day.” She left her native England in 1890 at the age of 23. She made her way to India, where she rescued girls from temple prostitution and established a home and school for them called Dohnavur Fellowship. She dreaded a life of singleness and was afraid of growing old alone. She once asked the Lord, “What can I do? How can I go on to the end?”The Lord comforted her: “None of them that trust in me shall be desolate.” She lived in singleness, serving in India for 50 years.Women also pioneered in missions in ways that did not necessarily involve ministry to women. Mary Slessor, inspired by the British explorer David Livingston, was a Scottish Presbyterian mill worker when she heard the call to serve in Africa. At the age of 27, in 1876, she entered Africa and made it to the interior of Calabar (present-day Nigeria), where her male predecessors had been unable to gain a foothold. She served for 38 years as a circuit preacher, winning over both men and women among indigenous peoples.Dwight L. Moody was a key advocate for women’s frontline ministry in newly developing city missions, which shaped women’s roles in his many ministries for decades after his death in 1899. “Moody and other evangelists experienced a chronic shortage of qualified Christian workers with a Bible education to assist in the inquiry room connected with revivals,” writes Janette Hassey in her book No Time for Silence (Zondervan/Academie, 1986). Moody recruited men and women to meet the intense demands of urban ministry, and invited Frances Willard, founder and president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, to assist him in his evangelistic work in Boston.She hesitated, fearing a female presence in a leadership role “might hinder the work among the conservatives.” Moody responded that it was just what they needed.Catherine Booth, Frances Nasmith, and Fanny Crosby (to name a few) also had a huge impact on city missions.Helen Sunday, the wife of the itinerant evangelist Billy Sunday, took her husband’s mantle after his death. Her story is told in Women Who Changed the Heart of the City (Kregel, 1997) by Delores T. Burger. After Sunday died in 1935, by his wife Helen’s account, “I went and knelt down in front of the bed; I put my head on Billy’s forearm as he lay there dead, and I said, ‘Lord, if there’s anything left in the world for me to do. … I promise you I’ll try to do the best I know how.'”After Billy was buried next to their three sons and daughter, his bereaved widow began a speaking ministry and served in rescue missions. “I love them because that’s where my Billy was saved,” she said. From 1935 to 1957, notes Burger, Helen Sunday became a “mother” to “thousands of rescue-mission workers and converts.”

Changing picture

The picture of women’s roles in missions began to change when two phenomena converged in the 20th century. First, mainline denominations grew in strength and influence, and eventually their national bureaucracies took over the agencies previously staffed and funded by the women’s missionary movement.”In each case, women fought and resisted the mergers but they were. … powerless to defend themselves because they had no laity rights in the church. … and no voice in the councils of their churches,” writes Robert.Second, the fundamentalist/modernist controversy erupted over the nature of Scripture, creation and evolution, and eschatology. As fundamentalists fought liberals who challenged the authority of Scripture, they increasingly limited women’s roles along the lines outlined in Paul’s two controversial passages (1 Corinthians 14 and 1 Timothy 2).The controversy “struck at the heart of the women’s missionary movement because it pitted the Bible against the ministry of women,” notes Robert. “The women’s missionary movement up to 1910. … was characterized by a holism that both affirmed women’s ministry and believed passionately in the evangelical mandates of the Bible. Missionary women spread the Good News to women and children through their teaching, medical work, and itinerant evangelism.”However, says Robert, “The resulting polarization helped destroy the balance between personal and social that was a key to the success of the women’s movement.”The energy and vision of the women’s missionary movement were lagging by the 1950s, and women’s roles in evangelical circles underwent a reversal. Women were no longer viewed as equal partners with men in ministry and service, as in the days of Moody and Willard. Postwar prosperity and the baby boom created a new paradigm that defined women as keepers of the domestic front.This, in turn, spurred a backlash: the feminist movement of the 1960s that challenged conventional definitions of women’s roles. Feminists raised the banner of individual rights, personal expression, and freedom from moral constraints. In its most radical expression, feminism ridiculed domesticity. This had catastrophic consequences for American culture, families, and, ironically, women. The evangelical church rightly took a strong stand against many of these misguided assumptions. But this response has also spawned what Ruth Tucker calls “neofundamentalism,” a movement that has imposed strict limits on how a woman can function in the kingdom of God. This, in turn, inevitably is affecting how women can function in missions.

The problem with world evangelism

In another irony, the urgency to get the gospel to every corner of the earth by the year 2000 has had a negative effect on women’s roles in missions, according to Catherine Allen. Allen worked for 25 years with the Southern Baptist Woman’s Missionary Union, finishing her stint as associate executive director in 1989, and served as president of the Baptist World Alliance’s women’s department from 1990 to 1995. Because of this new emphasis, she notes, some sending agencies have limited or eliminated “practical” ministries, usually staffed by women, in deference to “proclamation” ministries, usually staffed by men. Dana Robert shares Allen’s concern. “When mission gets redefined as ‘proclamation evangelism,’ and if you say women can’t be preachers, that de facto eliminates women’s work in mission,” Robert said in an interview.The Southern Baptist International Mission Board (IMB) stands as a case in point, according to Allen. Historically the Southern Baptists have been famous as a major force in missions, and today they have more appointed missionaries on the field than most mission agencies (approximately 5,000). As recently as 1991, she says, the IMB was “strongly recruiting women as missionaries and was encouraging women already there to take a proactive role in strategizing.” But since about 1993, the focus has been so narrowed to proclamation and church planting (the domain of men in the Southern Baptist Convention) that “many women have been displaced from productive roles.” Support for institutions and practical ministries, where women have excelled and flourished, has been reduced to the point of near-elimination.David Garrison, the IMB’s associate vice president for strategy coordination, agrees with Allen that the new mission strategy focuses on “evangelism that results in indigenous churches.””We would like to see communities of faith emerge. We help them get started and then leave them to the Lord. We’re always drawn to the frontiers,” Garrison says. He also concedes that practical ministries have been cut. But he says this is due less to the changing role of women than to the changing picture of missions.”We are in the age of having to go to a country and say, ‘What do you want?’ They aren’t saying, ‘We can’t take care of ourselves.’ They have great national pride,” he says. In other words, host countries aren’t pinpointing practical ministries as a point of need.Whatever the reasons, Allen expresses alarm at the decline in the percentage of women serving in the IMB’s ministries. “Baptist women in many countries are grieved at the loss of missionary coworkers,” she says.Brazil, before the early 1990s, saw phenomenal success in the IMB’s women’s ministries. Nine women, sent and funded by the IMB, worked full time in institutions (called Good Will Centers) that helped women. Today only one missionary and two Good Will Centers survive, “and these are weakened and imperiled,” she says.Even where the obstacles for women are not as pronounced, in most evangelical mission agencies women are not in the upper echelons of leadership where priorities are drawn and decisions made. “Women in their 30s, 40s and 50s, who are moving up the ladder, are having difficulty securing responsible positions in mission agencies,” notes Paula Harris, associate director of Urbana 2000. She described a planning retreat for the board of EFMA (Evangelical Foreign Missions Association) that consisted mostly of CEOs. Only one woman was listed among the plenary speakers. Her topic: “What Mission Leaders’ Wives Need To Know.””We focus on prayer, and the men are happy that women are praying. … But women can do a lot more,” says Lorry Lutz, international coordinator of the AD2000 women’s track. Lutz sees it less as an intentional effort to stifle women and more as a blind spot: “Men just don’t think of the fact they’re hurting women. A lot of these fellows get so gung-ho about what they’re doing, they forget to include the women.””By limiting half of the evangelical force that have legitimate spiritual gifts, we’re not hurting the cause of women so much as the cause of Christ,” says Jim Plueddemann, general director of SIM. “Let’s quit fighting the liberals and the radical feminists and get back to the task at hand.”

Needed: women for women

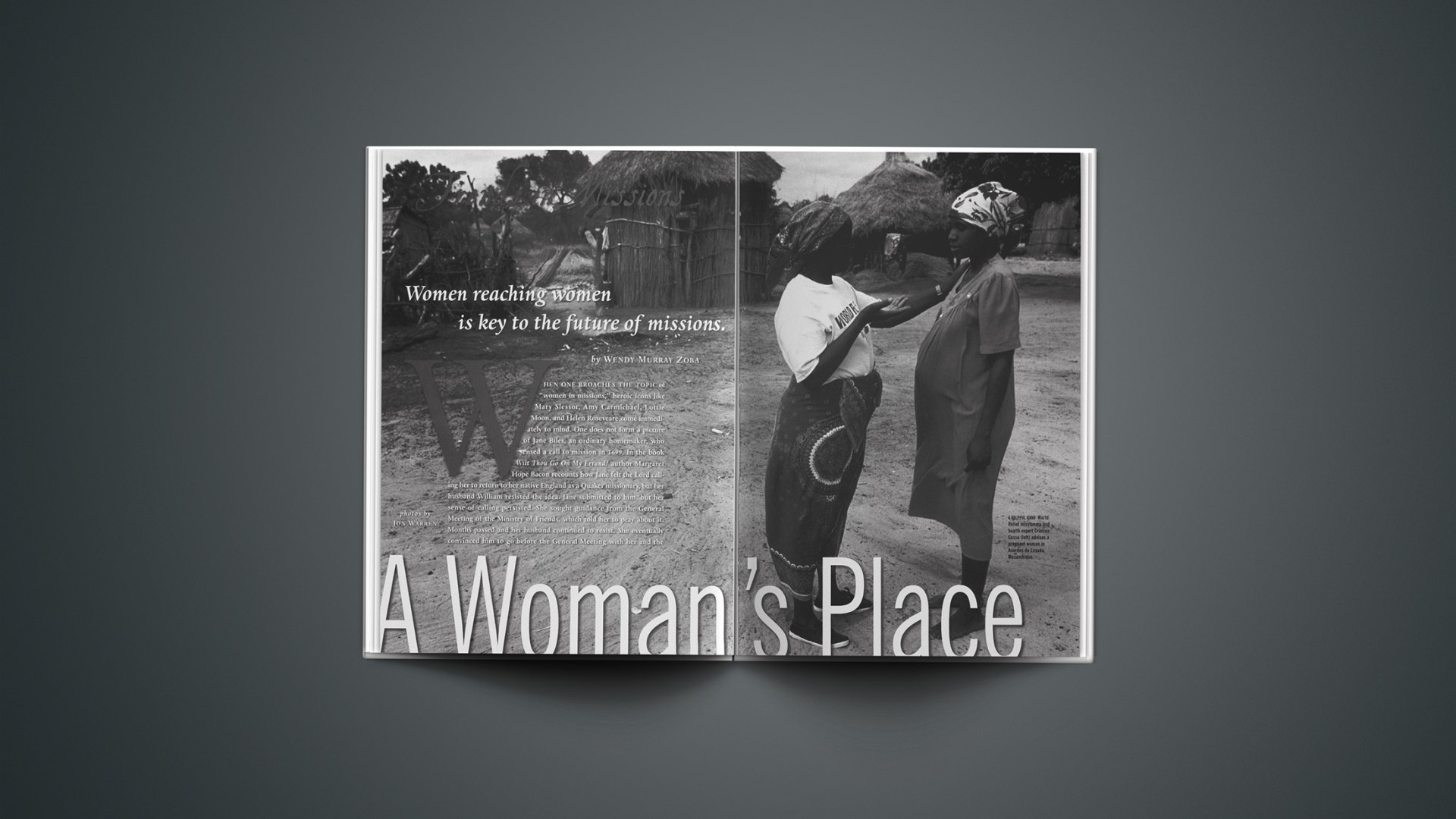

While these in-house battles are going on, stadiums in the U.S. are being packed with women trying to “renew the heart” and “bring back the joy.” Likened to a female version of Promise Keepers sprinkled with “gynecological humor” (Ruth Tucker’s term), these stadium gatherings are trying to help women find greater purpose and meaning in their often mundane middle-class lives. “There are a lot of women in a lot of pain who probably need to feel good about themselves,” says Lutz of ad2000. “But this undersells what a woman can do, and women settle for less than what God has gifted women to do. We don’t have to settle for floral arrangements and cake decorating.”What gave meaning and satisfaction to women in the past was “a call to mission and service,” says Allen. “Women are best helped by taking a big view of the world instead of wallowing in their own misery—by looking up, not in.”And when women do that, they’ll discover that there is a desperate need for women who will minister to other women (and their children) worldwide. “Women are the largest unreached people group in the world,” says Allen.Mission Frontiers points out that one in four of the world’s women is Muslim and 75 percent of those “live under restrictive governments where they are separated from access to education, healthcare services, and basic human rights.” There is a strong correlation between women’s education levels and child mortality rates and economic development, and 68 percent of female children worldwide reach only the fifth grade, according to the 1998–2000 Mission Handbook. The Red Cross estimates that women make up 70 percent of the world’s agriculture workforce, many as unpaid laborers. Furthermore, according to a United Nations report released in late May, “Violence against women and girls continues to be a global epidemic that kills, tortures, and maims—physically, psychologically, sexually, and economically.”As many as 20 to 50 percent of women worldwide have suffered either from neglect as a child or abuse from a husband or other relative. Many countries do not take the violence seriously because they view it as a private matter, the report said. The types of violence women face include incest, female circumcision, forced marriages, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, dowry beatings, general beatings, and domestic violence. Abuse cuts across economic lines, but poor women who are uneducated are more vulnerable. At the same time, women worldwide are “the growth points of the church.” According to Robert, women compose 80 percent of the members of house-churches in China; 70 percent in Latin American Pentecostal churches; and 70 to 80 percent of African churches. The largest church in Seoul, South Korea, has 700 pastors (most of them women), plus 52,000 neighborhood cells, which are led almost entirely by women.”Any time there is a church meeting in a home means women are leading there,” says Robert. SIM’s Plueddemann says, “In Africa, the most spiritual-minded people are the women. The women’s fellowship in one of their Nigerian communities is financially supporting their Nigerian missions.”Throughout the history of missions, women have become Christians as a result of other women who have touched them at their point of need—as teachers, health workers, reading tutors, or visiting neighbors. Women can reach the heart of other women and connect on a level that is closed to men.”It is impolite for men to be too much involved with women in the majority of international contexts, especially trying to meet their intimate needs,” Plueddemann says. And when the women find the Lord, the men often aren’t far behind. “The reason so many women flock to the church is because it’s good for their home,” says Robert. “If women can bring men into the church, they have a better home life. A woman with a Christian husband is better off than with a non-Christian husband who drinks or beats her.”

Women going forward

Some mission boards are making conscious attempts to include women in regional leadership positions and to empower them on the field. Interserve was started by women in the 1960s and has women in regional leadership positions throughout the world. Frontiers has sponsored conferences (including an upcoming one at Eastern College) to promote missions focusing specific ally on ministries to Muslim women.Plueddemann says that SIM has been intentional about placing women in leadership roles in its missions. Single women serve as directors of India and Ghana, and a married woman (and pastor) is director of Sudan. “We’ve got all kinds of opportunities, and we desperately need more women to do them,” he says.Mary Hawthorne serves with SIM in Bolivia with her husband, Steve, working with Quechuan women in the Bolivian highlands. One third of Bolivia’s population is Quechuan, and 94 percent of Quechuans live in rural settings cut off from basic services like healthcare, education, and housing. Women feel the brunt of this. Young uneducated girls fall prey to pregnancy by their teen years, typically have more children than they can care for, and often die young. They are illiterate and depend for their sustenance upon often abusive husbands or fathers.Mary holds weekly Bible studies in Quechuan for women “who have never heard that [they] share with men the glory and dignity of being created in God’s own image.” Over 40 women attend her Thursday-night gathering. Feliciana is one of them.Feliciana never attended school and bore 12 children by an abusive husband. She contracted tuberculosis, and it was only when she was near death (and her husband feared he’d be left alone to take care of the kids) that he took her to a doctor. When Feliciana first came to Mary’s Bible study, she insisted she was too stupid to learn the Bible verses or color the pictures. The other women encouraged her, and it wasn’t long before she was interacting on the same level as the other women.In addition to some agencies consciously recruiting women, two other trends in the missions picture bode well for women. The recent surge in short-term missions (one- to two-year assignments) has offered a plethora of service opportunities for women. Short-term projects often include teaching English, running vacation Bible schools, organizing literacy campaigns, doing medical stints, teaching high school, leading drama and mime—all of which require a hands-on approach that resonates with many women. (Many short-term assignments are volunteer posts for which the appointee pays all or most expenses.)Single women applicants for short-term assignments far outnumber single men across the board, including among Southern Baptists. Ruth Dougherty says that of the 179 short-term missionaries sent by TEAM last year, nearly 75 percent were women. “We don’t have very many single men,” she says.”We have many couples and many single women,” says Latin America Mission’s Susan Loobie, editor of The Evangelist. (She could think of only one single male missionary.)Plueddemann says that of the 2,000 active missionaries (including short-termers) with SIM, 75 percent are married and nearly all of the remaining 25 percent are women.

She changed a nation

The other encouraging trend is the shift away from the “imperialistic” missions model to one that is more indigenous and relational. Relief agencies are filling a gap here and many women are gravitating to this mode of service, and the agencies are thrilled to have them. Most are parachurch agencies and so can sidestep denominational policies that sometimes complicate possibilities for women.World Relief’s (WR) Joke van Opstal is a model for missions that points the way forward. Joke (pronounced “Yoka”—”It is not a ‘joke,'” she says), is a registered nurse who has served with WR in Cambodia’s killing fields since 1993. Cambodia has the highest death rate among children in East Asia; 17 percent of its children do not make it to their fifth birthday. Women are 64 percent of Cambodia’s population.WR went into squatter slums of Phnom Penh with its microenterprise development ministries (training women to run their own small businesses) but found that moms were distracted by the need to care for their children. To help women learn and grow, van Opstal began a puppet ministry to keep the kids occupied. But she has accomplished a lot more than babysitting.Through puppet stories, she dramatizes the need for better hygiene and tells children about a God who loves them. Rather than point a nagging finger warning children to wear shoes (so they won’t get worms), she’ll create a story about a little boy who runs faster and jumps higher because he wears shoes. “We go to communities and villages, basically wherever there is shade—under a tree or in front of somebody’s house, or under somebody’s house (if it’s on stilts). You want to be in a central place where everybody can see it. We do half healthcare stories and half evangelism,” she says.Over 15,000 of Cambodia’s children have been led to Christ through Joke’s puppets. This has brought their mothers to Christ, which has resulted in fathers and brothers also coming to Christ. Joke’s ministry alone has resulted in five church plants.Says WR president Clive Calver, “Microenterprise development means child survival. Child survival means Kids Clubs. Kids Clubs mean evangelism. Evangelism means church planting. Joke has pioneered in a unique and fantastic way with very little resources.”Van Opstal tells the story of one little girl in a church there who became a Christian and was later abducted, along with two friends, to be sold into prostitution. “A foreigner gave them a gas or something to make them drowsy and then took them to a room and told them to take everything off,” she says. “This little girl got scared and said, ‘I want to pray to Jesus. Do you want to pray with me?’ The other two girls were not Christians, but they told her that if she was going to pray, she better do it quickly.”They were praying,” she says, “and the girl told me it was like a wind blowing. Then, as soon as she said ‘Amen,’ somebody came into the room and realized he was in the wrong room. He said, ‘What are you doing here?’ The girls started crying, and he brought them back to their school and to safety.”Van Opstal’s puppet ministry reaches approximately 16,000 children a week through a staff of 56 Cambodians. In addition, she trains the staff of 56 Cambodians in Bible study, leadership, discipleship, and “walking in faith and the Spirit.” These leaders, in turn, take their training back to their churches. Joke’s coworkers have started 84 home churches.”Some of my heroes of the faith around the world are women,” Calver says. “Joke is one of them. She is changing a nation.”It may require the tenacity of Jane Biles, but if a woman seeks, she will find the opportunities to serve in a world of desperate need. “It is true that it’s a man’s world around the world,” says David Garrison of the SBC’s International Mission Board. “But it’s the women who show up.”

Wendy Murray Zoba is a senior writer for Christianity Today.

Related Elsewhere

To read more about some of the women who shaped the golden age of missions, visit the following sites:The city council of Dundee’s site has a biography of Mary Slessor ‘s life, with links to the mills where she worked, the churches she attended, and a recording of her voice speaking a tribal language. Slessor’s letters from Africa to Charles Partridge are available here, as well.Amy Carmichael wrote more than 35 books, including this short excerpt from Things as They Are. For a list of books by or about Carmichael ‘s life of service in India, click here.Lottie Moon is one the most famous Southern Baptist missionaries of all time. Read a short biography of Moon , or visit this list of links that describe the ministries that continue in her honor.The Sudan Internal Mission, commonly recognized as SIM, has its own homepage including the organization’s history and future outreach targets.There are separate pages for the Southern Baptist International Mission Board and the Southern Baptist Womens Mission Union . To read more about either organization you can contact the Southern Baptist Historical Society .Elizabeth Elliot’s biography of Amy Carmichael, A Chance to Die , and Bacon’s Wilt Thou Go On My Errand , and Robert’s American Women in Mission are all available from amazon.com.

Copyright © 2000 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.