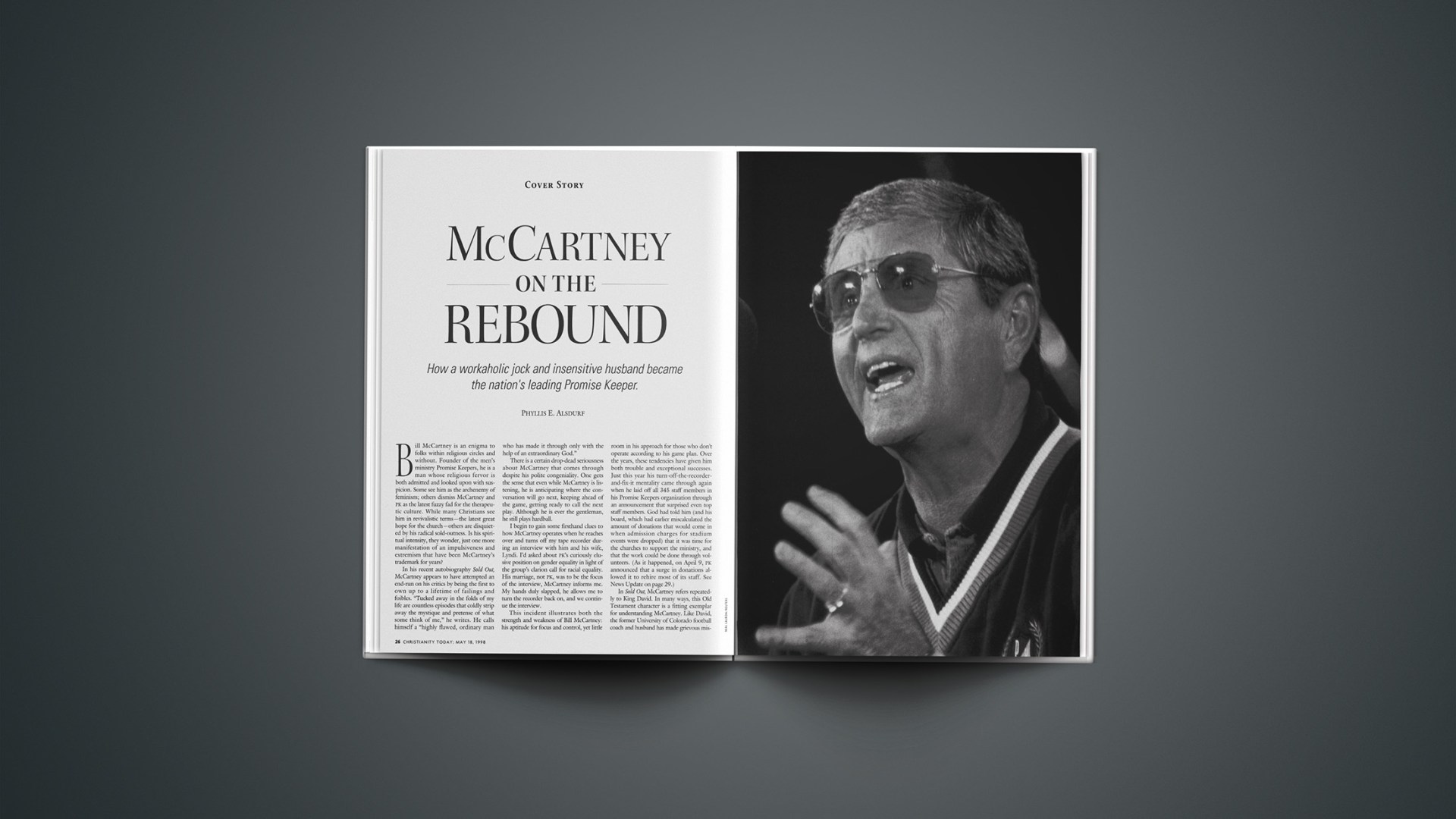

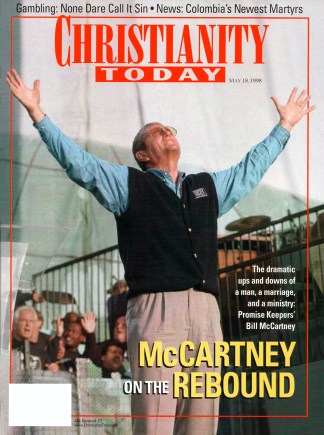

Bill McCartney is an enigma to folks within religious circles and without. Founder of the men’s ministry Promise Keepers, he is a man whose religious fervor is both admitted and looked upon with suspicion. Some see him as the archenemy of feminism; others dismiss McCartney and PK as the latest fuzzy fad for the therapeutic culture. While many Christians see him in revivalistic terms—the latest great hope for the church—others are disquieted by his radical sold-outness. Is his spiritual intensity, they wonder, just one more manifestation of an impulsiveness and extremism that have been McCartney’s trademark for years?

In his recent autobiography Sold Out, McCartney appears to have attempted an end-run on his critics by being the first to own up to a lifetime of failings and foibles. “Tucked away in the folds of my life are countless episodes that coldly strip away the mystique and pretense of what some think of me,” he writes. He calls himself a “highly flawed, ordinary man who has made it through only with the help of an extraordinary God.”

There is a certain drop-dead seriousness about McCartney that comes through despite his polite congeniality. One gets the sense that even while McCartney is listening, he is anticipating where the conversation will go next, keeping ahead of the game, getting ready to call the next play. Although he is ever the gentleman, he still plays hardball.

I begin to gain some firsthand clues to how McCartney operates when he reaches over and turns off my tape recorder during an interview with him and his wife, Lyndi. I’d asked about PK’s curiously elusive position on gender equality in light of the group’s clarion call for racial equality. His marriage, not PK, was to be the focus of the interview, McCartney informs me. My hands duly slapped, he allows me to turn the recorder back on, and we continue the interview.

This incident illustrates both the strength and weakness of Bill McCartney: his aptitude for focus and control, yet little room in his approach for those who don’t operate according to his game plan. Over the years, these tendencies have given him both trouble and exceptional successes. Just this year his turn-off-the-recorder-and-fix-it mentality came through again when he laid off all 345 staff members in his Promise Keepers organization through an announcement that surprised even top staff members. God had told him (and his board, which had earlier miscalculated the amount of donations that would come in when admission charges for stadium events were dropped) that it was time for the churches to support the ministry, and that the work could be done through volunteers. (As it happened, on April 9, PK announced that a surge in donations allowed it to rehire most of its staff. See News Update on page 29.)

In Sold Out, McCartney refers repeatedly to King David. In many ways, this Old Testament character is a fitting exemplar for understanding McCartney. Like David, the former University of Colorado football coach and husband has made grievous mistakes, but also like David, he has humbled himself and mended his ways as the Holy Spirit has convicted him of particular sins. While not always pretty, McCartney’s story, like David’s, is ultimately about growing obedience and big flaws redeemed by a radical, even heroic, faith.

Through Lyndi’s eyesSold Out is presented as McCartney’s story, but the book also contains nine sections written by Lyndi. They provide a good window into McCartney’s spiritual journey, and they helped him write a book that was “closer to the truth,” he says. Lyndi reveals the monumental price she paid as McCartney’s “trophy wife,” a woman who for years stood on the sidelines while McCartney coached the University of Colorado’s football team to a national championship. They also help underscore what brought their never-great marriage to a crisis in 1993, when Lyndi says she found herself in “an emotional deep-freeze.”

That year began in soap-opera fashion when, on New Year’s Day, Bill came clean to Lyndi about an affair he had had with another woman two decades earlier in their marriage. That confession, which the McCartneys chose not to put in the book but which was reported by the New York Times last fall, left Lyndi devastated. At the time, McCartney was at the pinnacle of his coaching career and riding high with PK involvements. In a manner typical of the way McCartney operated at the time, he confessed his adultery just moments before walking out the door to coach a Fiesta Bowl game.

In the months that followed, Lyndi’s emotional and physical health reached the breaking point. To cope, she rarely left the bedroom of their home in Boulder, Colorado. There she contemplated taking her own life. For more than seven months she vomited every day, losing 80 pounds. McCartney, busy with football and with managing the burgeoning Promise Keepers movement, remained oblivious.

“I thought she was just exercising discipline,” McCartney told the New York Times. “I saw her losing weight, but I didn’t see it as a bad thing. You know how ladies are concerned about the pounds. I saw that she was losing weight, and I was proud of her.”

While Lyndi had no intention of leaving her marriage, she says she began building “emotional siege walls” between herself and Bill. “The Lord was the only one I felt I could trust.”

The daughter of a southern California screenwriter father, she says her childhood dreams were “to sing, to dance, to act, to write.” Her home was a place where the arts were emphasized and celebrities were entertained. “The glitz, glitter, and romance of Hollywood greatly influenced my life,” she says. “I believed in ‘happily ever afters.’ “

While a student at Stephens College, a prestigious women’s school in Columbia, Missouri, she met Bill, a football player for the University of Missouri. They married when Bill was 22 years old and Lyndi only 19. Lyndi quickly learned that she would have to adjust to Bill’s destructive drinking binges, from which he often returned drunk. She also learned she would need to adapt to the many spur-of-the-moment, unilateral decisions he made.

For example, early in the marriage, McCartney uprooted his nine-month-pregnant wife without consulting her when a better coaching position became available—and then left her for a weekend of hunting with his newfound coaching buddies an hour after they had arrived at their new home. A year after that, he interpreted a phone call about another coaching job as God’s direction that it was time to move again. The call came just minutes after he’d returned to his pregnant wife and eight-month-old son from a weekend away from home. McCartney had the family in the car headed for his new job within 20 minutes.

Lyndi claims she wasn’t bothered by Bill’s lack of attention during their 30-year marriage “most of the time.” And she stayed reasonably happy with her responsibilities as a mother of four “most of the time.” But she also admits that they lived separate lives. As her husband soared to the pinnacle of his career, “I just felt like I was getting smaller and smaller and smaller,” she recalls.

The recent renewal within the McCartneys’ marriage to a large degree has been about Lyndi recovering her voice and regaining a sense of who she is. Describing herself as “bolder, stronger, and not nearly so intimidated as I once was,” Lyndi says she “needed to be heard” by Bill. “I feel like I’m even recovering my personality, which had kind of disappeared too,” she notes.

For his part, Bill says he is learning to listen to Lyndi. The result has been “sweeter and sweeter harmony” between them, he claims. To fulfill what he sees as his God-given responsibility to bring Lyndi “to splendor,” Bill now budgets his time “to give the Lord and my wife top priority.”

God’s drunken zealot McCartney has never done anything halfway. Raised in a blue-collar Michigan family that was sold out to all things Irish, Catholic, Democrat, and Marine Corps, McCartney says lukewarmness or indifference were “foreign concepts” to him. He distinguished himself early not only for his athletic abilities but also for his knowledge of sports. As a young boy, he also had an “insatiable zeal to know God,” which translated into a disciplined commitment to the Catholic church. “I attended mass every day,” McCartney remembers. “I literally went ten years without missing daily Communion.”

Sold Out describes early manifestations of McCartney’s religious fervor. As a seven-year-old at a Catholic school Christmas party in Trenton, Michigan, he began to beseech God when he learned that a new wallet would be included in a grab bag of gifts for the children. When his turn came, he reached into the bag with his eyes obediently closed and promised God he would do anything for him if he would just allow him to pull out the wallet. When he did, young Bill began to reason, “If I could call on God for something like a five dollar wallet, what else could I pray for?

“It confirmed everything I’d been hearing in catechism and already strongly suspected: There really is a God,” McCartney remembers thinking. “He really does love me. I could actually talk to the God of the universe and expect him to hear.”

By the time he entered college, his zeal had grown dogmatic. McCartney once warned his college roommate—the son of a Protestant minister—that “he was going to hell because he was not Catholic.” During a summer break of corresponding with Lyndi, his girlfriend, he carefully printed the initials JMJ on the top of each letter. Standing for Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, the insignia was one that McCartney had been using faithfully since his Catholic grade-school days.

An even more telling example of McCartney’s spiritual disposition occurred at a sorority party his senior year. He was drinking beer with other jocks when, from across the room, he overheard Lyndi, his new girlfriend, casually use God’s name in vain. “Using God’s name in vain at all, much less around my teammates, for heaven’s sake, was like committing the unpardonable sin,” he writes. “Never mind that I was obnoxiously ignoring my own drunken stupor. I clamped down on her innocent slip with all the irrational fury of a pit bull. I exploded. To her shock, I turned mean and berated her for her careless blasphemy.”

Lyndi tried to apologize, but McCartney hustled her out to the car and drove her recklessly to her dorm. Arriving in a drunken fury, he skidded into the side of an occupied police car parked there. Before a crowd of Lyndi’s dormmates who had heard the crash, McCartney boisterously resisted the arresting officer. Even when handcuffed, McCartney wrestled free just long enough to return to Lyndi, hug her as best he could, and announce loudly, “Oh Lyndi, I love you!”

The incident cost him his football scholarship, but not his girlfriend, who had been dreaming of the day McCartney would express his love for her for the first time—even if not quite in this manner. In Sold Out, Lyndi wryly observes that “Bill first told me he loved me while he was handcuffed to a police officer. … The next time he told me he loved me, he got my name wrong. He used his old girlfriend’s name. That was perhaps my first clue that Bill was a paradox.”

Bill remained a paradox to her in marriage. He rose quickly through high-school coaching positions to more lucrative college contracts—all the while giving Lyndi and the four children less and less time. But even as he put in 16-hour days six days a week and continued drinking compulsively during the noncoaching season, he remained passionate in his desire to serve God. Often he would rise at four or five in the morning and go to early mass to confess his drunkenness and other sins from the day before.

“Society told me I was doing the right thing,” McCartney says about his long work hours. “I got compensated commensurate with somebody who was doing something important. In reality [coaching] had stolen the first place in my life from what should have been there, what I thought was there, and what I told people was there.”

Promise procrastinator To this day, people are amazed to learn that the McCartneys’ marriage was floundering even after he started Promise Keepers. It also continues to amaze the sports world that Coach McCartney abruptly resigned in December 1993, following another stellar season at the University of Colorado. Both facts reflect on McCartney’s spiritual pilgrimage.

When he began Promise Keepers in 1990, McCartney truly believed that his marriage and family life were fine. But, he now acknowledges, he was out of touch. If he was busy with coaching before starting Promise Keepers, he was even busier afterward. His all-or-nothing commitment to both coaching and PK, McCartney says, allowed him to camouflage the hypocrisy of his personal life. “It may sound unbelievable,” he writes, “but while Promise Keepers was spiritually inspiring to my core, my hard-charging approach to the ministry was distracting me from being, in the truest sense, a promise keeper to my own family.”

God used two events to turn McCartney around. One was a PK rally where men were told to write down the number their wives would give their marriages if rating them on a scale of one to ten. He had to admit with embarrassment to the other men on the platform that Lyndi—the wife of the founder of Promise Keepers—would probably only give their marriage a six.

Then, in the fall of 1994, a guest speaker at the Vineyard Fellowship church the McCartneys attended in Boulder pointedly stated: “If you want to know about a man’s character, then look into the face of his wife. Whatever he has invested in or withheld from her will be reflected in her countenance.” That word did to McCartney what the prophet Nathan’s story about the rich man’s stealing a poor man’s sheep did to King David. Literally turning to face his wife, McCartney saw in his wife’s haunted, empty eyes his own sinful neglect staring back at him. “Escorting my wounded wife out to the church parking lot,” McCartney writes, “I began to pray about the timing of my resignation from the University of Colorado.”

“God told me … “ One of Bill McCartney’s strengths is that he will act when he believes God has told him to do something—regardless of the consequences. Determined that rebuilding his marriage would require drastic action, in November 1994, he announced that he was retiring from coaching in order to spend time with Lyndi. To do so, he gave up the ten years remaining on his $350,000-a-year contract. Sports Illustrated called it “un-American.”

“I thought he would wind up hating me,” Lyndi says. In actuality, it marked a turning point in their marriage. “It was symbolic to me because he was giving up something he loved very much for us. He gave it up for the Lord, but it was for us, too, for our relationship.”

McCartney, who took his family from the Catholic church in 1988 to join the Boulder Valley Vineyard, speaks the language and world-view of the charismatic Vineyard fellowship of churches. For example, he writes that God drove the nail into the coffin of his football aspirations through “a word” from Randy Phillips, then president of Promise Keepers. “Mac,” McCartney says Randy told him, “first of all I’m coming to you as a brother in Christ. I’m not here on my own accord. What I’m going to share with you, I truly believe is from the Lord. … I’m not saying you should quit coaching at Colorado. I believe the Lord would have me tell you that you’re not supposed to coach anywhere next year.”

McCartney continues: “I could tell Randy had heard from the Lord and had tested it long in prayer. It was new territory for me. … I closed my eyes for a moment and sensed the Holy Spirit’s soft, calming confirmation. Then I looked Randy square in the eye. ‘Phillips, I’m accepting what you’ve told me on faith. I receive it as a word from the Lord.’ “

McCartney’s slow journey out of the Catholic church had begun in 1974 when he was “born again” at a Campus Crusade for Christ event that one of his players had invited him to attend. As Christian athletes at the meeting shared their testimonies, McCartney says in his autobiography, “I suddenly understood that while I loved God, knew Jesus Christ was His Son, and certainly considered myself saved, I needed to make the simple request, ‘Jesus Christ, please save me.’ … I needed God’s healing power to fight off the craving of alcohol. Instead, I was pinning my hopes on a program. A static routine. A passive ritual. What I needed was a relationship.”

His conversion began to transform some areas of his life. After reading that John Wesley had fasted every Wednesday and Friday from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., he began a similar fasting pattern, and he quit a three-pack-a-day cigarette habit. Eventually, he and his family began attending a “Spirit-filled” Catholic church.

His struggle with the bottle, however, would last off and on another 16 years, until July 1990, when he pledged himself to abstinence. It was the only approach that truly allowed him to kick the habit, Lyndi writes, since “once he took one drink, he was out of control again.” As McCartney became serious about kicking his drinking habit, he “immediately, perhaps even callously, cut ties with some very good friends of ours” who drank, he recalls in Sold Out. “I didn’t take into account how this might strike [Lyndi]. There was no discussion to it.”

The foreword to Sold Out reveals another example of McCartney’s on-a-mission-from-God outlook. Just as McCartney would consecrate his football program to Jesus Christ on the day he was hired by the University of Colorado, and just as he would hear God telling him before one important game, Do not fear, for I will go before you. … This battle belongs to Me!, so too the very writing of Sold Out is considered a work of great spiritual importance by all involved. In the foreword, literary agent and lawyer Sealy Yates states that “McCartney told David Halbrook [McCartney’s writer] and me that it was imperative for us to diligently seek God’s will regarding whether we should join with McCartney to write and publish this book … because God has such a purpose for them with respect to the delivery and distribution of that book, Satan and his armies intend to do all they can to attack and defeat them and all God has for them to do in that regard.” The foreword ends with a list of spiritual attacks Yates believes did indeed occur during the publishing process.

McCartney’s a the-buck-stops-here kind of guy with years of practice at being in charge.

When it came to my own interview with them, Bill informs me, I was granted it on CHRISTIANITY TODAY’s behalf only because the Holy Spirit had cleared my name through the publicist. Other interview requests, he lets me know, had been denied.

Ever the coach, McCartney will always remain comfortable with hierarchical structures in which he is calling the shots, taking responsibility, directing the game plan. He’s a the-buck-stops-here kind of guy with years of practice at being in charge.

In Sold Out, Lyndi notes that the concept of a man “seeing his wife as a teammate is a recent revelation for Bill. You’d have to find another analogy to fit how he viewed our relationship during most of our thirty-four years of marriage. He may have seen me as a loyal cheerleader, which I was; or perhaps he saw himself as the coach and me as someone desperately trying to make his team. … “

She concludes cautiously: “I must admit that while the Lord is showing Bill that I am his teammate, we’re still growing into this reality, little by little. I think it’s hard for Bill to see himself as anything other than the coach.”

McCartney says there is no turning back for him on this issue. “Now that I’m tasting and experiencing the relationship that God always intended in our marriage, it’s thrilling! I mean, I think about it during the day. It’s on my heart. It’s not just a passing thought before I walk in the door. We’ve entered into that kind of really rich relationship that has the love, the respect, the unity. It’s a real honoring process.”

Whatever McCartney’s “blinders,” which he admits he still has, his childlike craving to serve God and his willingness to be corrected set McCartney apart from lukewarm Christians. Describing himself as “theologically unbending,” McCartney recognizes that his passionate pursuit of his life goals—spiritual and otherwise—has not made him popular with some Christians. “There are many who are within the Kingdom family who are ashamed of me,” he writes. “They want to apologize for me. They want to disassociate from me.”

This is a man who, in 1996, in preparation for a PK pastors conference, fasted 40 days, dropping from 206 to 184 pounds. On day 39, he writes, God “told me specifically why He had called me to such an extensive fast. Reading John 4:34, in which Jesus says, ‘My food is to do the will of him who sent me,’ I suddenly knew. That’s it! … He awoke me to the fact that my food, my sustenance, literally, is to do His will. That’s where the power lies in a Christian’s life. Do His will.” Like Sonny Dewey, that engaging Pentecostal evangelist portrayed in Robert Duvall’s The Apostle, McCartney’s evangelistic zeal in the present is still haunted by the sins and excesses of the past. As McCartney well knows, “sold-outness” to a goal can quickly become a drivenness that all but destroys those caught in its wake. “A thin line separates ‘sold out’ from ‘sell out,’ ” McCartney concludes in his autobiography. But that does not diminish the urgency he feels to make God’s will his sustenance. And indeed, as he puts John 4:34 into practice—especially the part about remembering where true power lies—it’s enough to make McCartney a man after God’s own heart.

Phyllis Alsdurf is a doctoral student in journalism and mass communication at the University of Minnesota.

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.