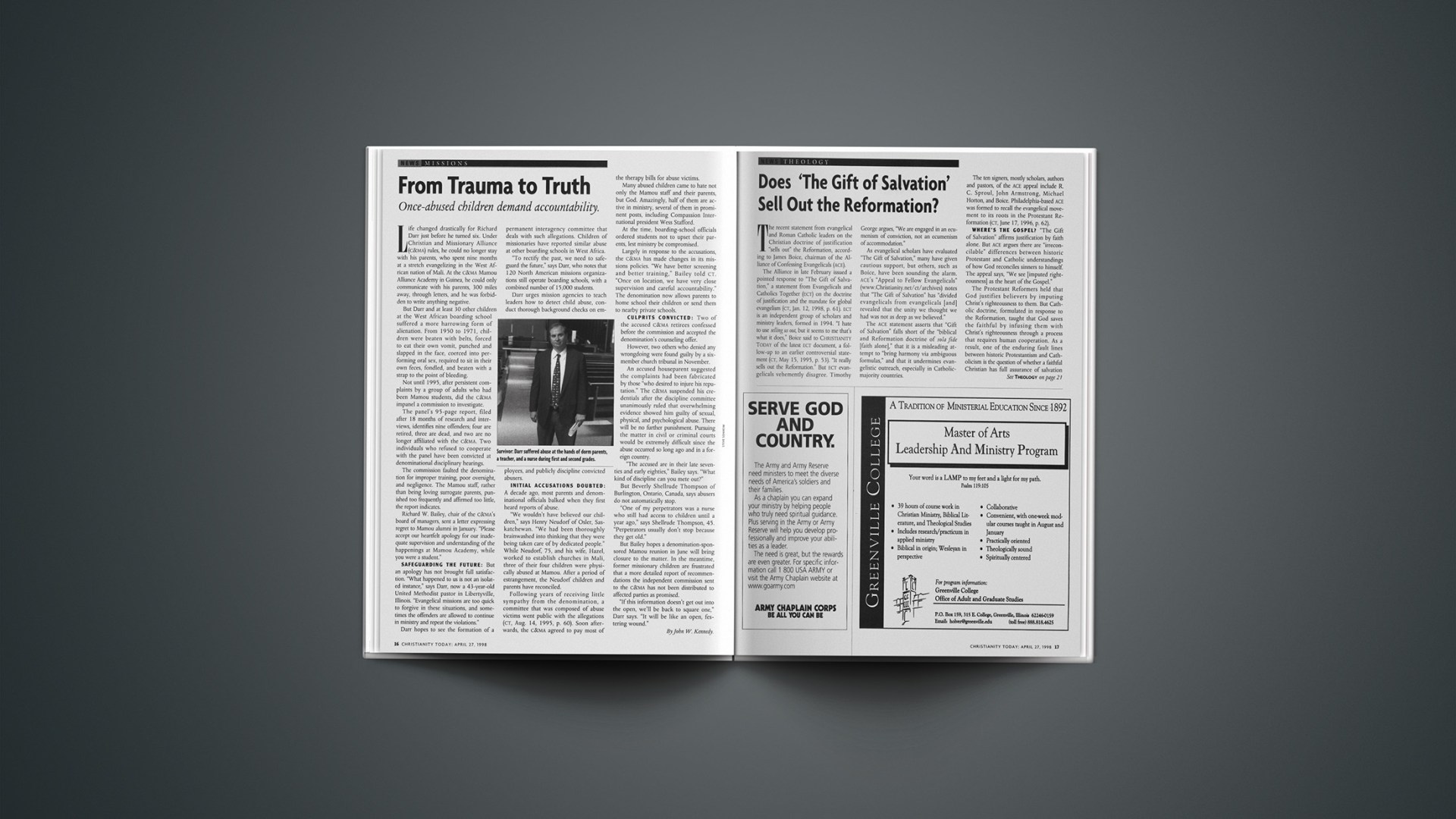

Life changed drastically for Richard Darr just before he turned six. Under Christian and Missionary Alliance (C&MA) rules, he could no longer stay with his parents, who spent nine months at a stretch evangelizing in the West African nation of Mali. At the C&MA Mamou Alliance Academy in Guinea, he could only communicate with his parents, 300 miles away, through letters, and he was forbidden to write anything negative.

But Darr and at least 30 other children at the West African boarding school suffered a more harrowing form of alienation. From 1950 to 1971, children were beaten with belts, forced to eat their own vomit, punched and slapped in the face, coerced into performing oral sex, required to sit in their own feces, fondled, and beaten with a strap to the point of bleeding.

Not until 1995, after persistent complaints by a group of adults who had been Mamou students, did the C&MA impanel a commission to investigate.

The panel’s 95-page report, filed after 18 months of research and interviews, identifies nine offenders; four are retired, three are dead, and two are no longer affiliated with the C&MA. Two individuals who refused to cooperate with the panel have been convicted at denominational disciplinary hearings.

The commission faulted the denomination for improper training, poor oversight, and negligence. The Mamou staff, rather than being loving surrogate parents, punished too frequently and affirmed too little, the report indicates.

Richard W. Bailey, chair of the C&MA’s board of managers, sent a letter expressing regret to Mamou alumni in January. “Please accept our heartfelt apology for our inadequate supervision and understanding of the happenings at Mamou Academy, while you were a student.”

SAFEGUARDING THE FUTURE: But an apology has not brought full satisfaction. “What happened to us is not an isolated instance,” says Darr, now a 43-year-old United Methodist pastor in Libertyville, Illinois. “Evangelical missions are too quick to forgive in these situations, and sometimes the offenders are allowed to continue in ministry and repeat the violations.”

Darr hopes to see the formation of a permanent interagency committee that deals with such allegations. Children of missionaries have reported similar abuse at other boarding schools in West Africa.

“To rectify the past, we need to safeguard the future,” says Darr, who notes that 120 North American missions organizations still operate boarding schools, with a combined number of 15,000 students.

Darr urges mission agencies to teach leaders how to detect child abuse, conduct thorough background checks on employees, and publicly discipline convicted abusers.

INITIAL ACCUSATIONS DOUBTED: A decade ago, most parents and denominational officials balked when they first heard reports of abuse.

“We wouldn’t have believed our children,” says Henry Neudorf of Osler, Saskatchewan. “We had been thoroughly brainwashed into thinking that they were being taken care of by dedicated people.” While Neudorf, 75, and his wife, Hazel, worked to establish churches in Mali, three of their four children were physically abused at Mamou. After a period of estrangement, the Neudorf children and parents have reconciled.

Following years of receiving little sympathy from the denomination, a committee that was composed of abuse victims went public with the allegations (CT, Aug. 14, 1995, p. 60). Soon afterwards, the C&MA agreed to pay most of the therapy bills for abuse victims.

Many abused children came to hate not only the Mamou staff and their parents, but God. Amazingly, half of them are active in ministry, several of them in prominent posts, including Compassion International president Wess Stafford.

At the time, boarding-school officials ordered students not to upset their parents, lest ministry be compromised.

Largely in response to the accusations, the C&MA has made changes in its missions policies. “We have better screening and better training,” Bailey told CT. “Once on location, we have very close supervision and careful accountability.” The denomination now allows parents to home school their children or send them to nearby private schools.

CULPRITS CONVICTED: Two of the accused C&MA retirees confessed before the commission and accepted the denomination’s counseling offer.

However, two others who denied any wrongdoing were found guilty by a six-member church tribunal in November.

An accused houseparent suggested the complaints had been fabricated by those “who desired to injure his reputation.” The C&MA suspended his credentials after the discipline committee unanimously ruled that overwhelming evidence showed him guilty of sexual, physical, and psychological abuse. There will be no further punishment. Pursuing the matter in civil or criminal courts would be extremely difficult since the abuse occurred so long ago and in a foreign country.

“The accused are in their late seventies and early eighties,” Bailey says. “What kind of discipline can you mete out?”

But Beverly Shellrude Thompson of Burlington, Ontario, Canada, says abusers do not automatically stop.

“One of my perpetrators was a nurse who still had access to children until a year ago,” says Shellrude Thompson, 45. “Perpetrators usually don’t stop because they get old.”

But Bailey hopes a denomination-sponsored Mamou reunion in June will bring closure to the matter. In the meantime, former missionary children are frustrated that a more detailed report of recommendations the independent commission sent to the C&MA has not been distributed to affected parties as promised.

“If this information doesn’t get out into the open, we’ll be back to square one,” Darr says. “It will be like an open, festering wound.”

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.