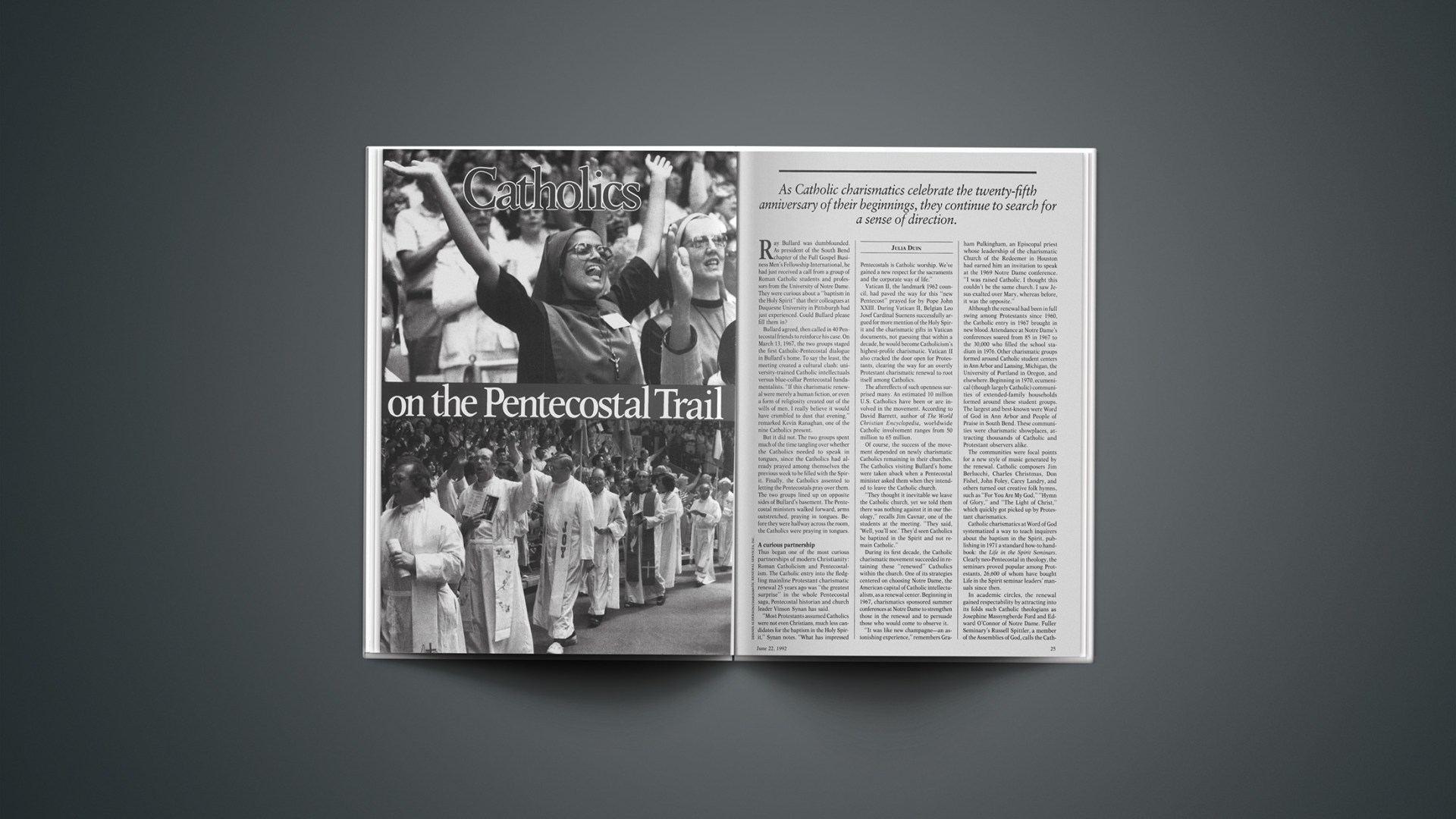

As Catholic charismatics celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of their beginnings, they continue to search for a sense of direction.

Ray Bullard was dumbfounded. As president of the South Bend chapter of the Full Gospel Business Men’s Fellowship International, he had just received a call from a group of Roman Catholic students and professors from the University of Notre Dame. They were curious about a “baptism in the Holy Spirit” that their colleagues at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh had just experienced. Could Bullard please fill them in?

Bullard agreed, then called in 40 Pentecostal friends to reinforce his case. On March 13, 1967, the two groups staged the first Catholic-Pentecostal dialogue in Bullard’s home. To say the least, the meeting created a cultural clash: university-trained Catholic intellectuals versus blue-collar Pentecostal fundamentalists. “If this charismatic renewal were merely a human fiction, or even a form of religiosity created out of the wills of men, I really believe it would have crumbled to dust that evening,” remarked Kevin Ranaghan, one of the nine Catholics present.

But it did not. The two groups spent much of the time tangling over whether the Catholics needed to speak in tongues, since the Catholics had already prayed among themselves the previous week to be filled with the Spirit. Finally, the Catholics assented to letting the Pentecostals pray over them. The two groups lined up on opposite sides of Bullard’s basement. The Pentecostal ministers walked forward, arms outstretched, praying in tongues. Before they were halfway across the room, the Catholics were praying in tongues.

A Curious Partnership

Thus began one of the most curious partnerships of modern Christianity: Roman Catholicism and Pentecostalism. The Catholic entry into the fledgling mainline Protestant charismatic renewal 25 years ago was “the greatest surprise” in the whole Pentecostal saga, Pentecostal historian and church leader Vinson Synan has said.

“Most Protestants assumed Catholics were not even Christians, much less candidates for the baptism in the Holy Spirit,” Synan notes. “What has impressed Pentecostals is Catholic worship. We’ve gained a new respect for the sacraments and the corporate way of life.”

Vatican II, the landmark 1962 council, had paved the way for this “new Pentecost” prayed for by Pope John XXIII. During Vatican II, Belgian Leo Josef Cardinal Suenens successfully argued for more mention of the Holy Spirit and the charismatic gifts in Vatican documents, not guessing that within a decade, he would become Catholicism’s highest-profile charismatic. Vatican II also cracked the door open for Protestants, clearing the way for an overtly Protestant charismatic renewal to root itself among Catholics.

The aftereffects of such openness surprised many. An estimated 10 million U.S. Catholics have been or are involved in the movement. According to David Barrett, author of The World Christian Encyclopedia, worldwide Catholic involvement ranges from 50 million to 65 million.

Of course, the success of the movement depended on newly charismatic Catholics remaining in their churches. The Catholics visiting Bullard’s home were taken aback when a Pentecostal minister asked them when they intended to leave the Catholic church.

“They thought it inevitable we leave the Catholic church, yet we told them there was nothing against it in our theology,” recalls Jim Cavnar, one of the students at the meeting. “They said, ‘Well, you’ll see.’ They’d seen Catholics be baptized in the Spirit and not remain Catholic.”

During its first decade, the Catholic charismatic movement succeeded in retaining these “renewed” Catholics within the church. One of its strategies centered on choosing Notre Dame, the American capital of Catholic intellectualism, as a renewal center. Beginning in 1967, charismatics sponsored summer conferences at Notre Dame to strengthen those in the renewal and to persuade those who would come to observe it.

“It was like new champagne—an astonishing experience,” remembers Graham Pulkingham, an Episcopal priest whose leadership of the charismatic Church of the Redeemer in Houston had earned him an invitation to speak at the 1969 Notre Dame conference. “I was raised Catholic. I thought this couldn’t be the same church. I saw Jesus exalted over Mary, whereas before, it was the opposite.”

Although the renewal had been in full swing among Protestants since 1960, the Catholic entry in 1967 brought in new blood. Attendance at Notre Dame’s conferences soared from 85 in 1967 to the 30,000 who filled the school stadium in 1976. Other charismatic groups formed around Catholic student centers in Ann Arbor and Lansing, Michigan, the University of Portland in Oregon, and elsewhere. Beginning in 1970, ecumenical (though largely Catholic) communities of extended-family households formed around these student groups. The largest and best-known were Word of God in Ann Arbor and People of Praise in South Bend. These communities were charismatic showplaces, attracting thousands of Catholic and Protestant observers alike.

The communities were focal points for a new style of music generated by the renewal. Catholic composers Jim Berlucchi, Charles Christmas, Don Fishel, John Foley, Carey Landry, and others turned out creative folk hymns, such as “For You Are My God,” “Hymn of Glory,” and “The Light of Christ,” which quickly got picked up by Protestant charismatics.

Catholic charismatics at Word of God systematized a way to teach inquirers about the baptism in the Spirit, publishing in 1971 a standard how-to handbook: the Life in the Spirit Seminars. Clearly neo-Pentecostal in theology, the seminars proved popular among Protestants, 26,600 of whom have bought Life in the Spirit seminar leaders’ manuals since then.

In academic circles, the renewal gained respectability by attracting into its folds such Catholic theologians as Josephine Massyngberde Ford and Edward O’Connor of Notre Dame. Fuller Seminary’s Russell Spittler, a member of the Assemblies of God, calls the Catholic contribution to charismatic theology “substantial.” In 15 years, he says, the volume of Catholic charismatic literature equaled that produced over 75 years by Pentecostal theologians. The South African charismatic and Reformed theologian Henry Lederle agrees that Catholic theologians made a persuasive case for the renewal. “O’Connor’s 1971 book, The Pentecostal Movement in the Catholic Church, was the most influential book for the charismatic movement in South Africa,” says Lederle, who now teaches at Oral Roberts University in Tulsa. “It was that book that influenced [Capetown Anglican Archbishop Bill] Burnett to become charismatic.”

Unlike leaders of many Protestant denominations, the Catholic hierarchy swiftly endorsed the movement. Within eight years of its inception, Pope Paul VI called it “a chance for the church” while addressing 10,000 charismatics gathered in Rome in 1975. Considering the glacial speed at which Rome normally operates, the Catholic church’s imprimatur on the renewal caught the attention of theologically conservative Protestants who had written off the charismatic renewal as pure emotion and experience, Lederle argues. “Pentecostals have been saying for a long time that Spirit baptism was normative, but now reputable Catholic scholars were saying that. When Catholic scholars began breaking down theories of dispensationalism, the Reformed Church in America in 1973 and 1975 put out synodical documents that said they couldn’t limit the gifts of the Spirit to the time of the apostles. They decided God was sovereign enough to move today if he wanted to.”

Pulling Out The Stops

By the mid-1970s, Protestant and Catholic charismatic leaders had known each other for almost a decade. Confident that the charismatic movement was here to stay, they combined forces in 1977 to stage the first Conference on Charismatic Renewal in the Christian Churches. Held in Kansas City, the conference pulled out all the stops by bringing together about a dozen denominations, many of which had never worked together. The conference committee was chaired by Ranaghan, a Catholic. Plenary speakers included Suenens, black Pentecostal James Forbes, and Southern Baptist Ruth Carter Stapleton. About 45,000 people attended the four-day conference, half of them Catholics. Nearly as impressive was a conference in June 1982 in Strasbourg, France, where charismatic Protestant and Catholic Europeans worshiped together not all that far from where Martin Luther pinned his 95 theses to the Wittenberg church door. For the first time, Protestants and Catholics joined the same renewal movement.

Even before Kansas City, American Lutherans were welcoming Catholics. Starting in 1971, they planned a “Catholic night” at each of their yearly charismatic conferences in Minneapolis to bring in speakers such as Suenens and Dominican priest Francis MacNutt.

“It’s a common experience that opens the way to unity,” said Lutheran renewal leader Larry Christenson. “With that comes an adherence to Scripture as the final authority. I’ve never heard an argument about the Virgin Birth or the divinity of Christ at charismatic conferences. We’re very keenly aware of theological differences, but we don’t see that as hindering places where we have agreement.”

Where they did not agree included inter-Communion. Francis MacNutt remembered attending a Notre Dame conference where one out of ten persons present was Protestant. Yet, after a sermon on John 6, where Jesus speaks of being the Bread of Life, Protestants were reminded that they were not allowed to share the Eucharist. MacNutt and a few others walked out.

“It was an awful way to handle it, especially after that gospel,” he said. “If you have an ecumenical service, then don’t have Communion. Have something else.” MacNutt himself was excommunicated from the Catholic church in 1980 when he married after John Paul II refused to laicize him. “Most Catholics say [disunity] pains them,” MacNutt says, “but it doesn’t pain them that much.”

On the grassroots level, Protestants and Catholics were enjoying an informal unity through a network of prayer meetings and nondenominational groups such as Women’s Aglow and the Full Gospel Business Men’s Association. Catholic charismatic prayer meetings attracted more liturgically minded Protestants who disliked boisterous Pentecostal worship.

“Before we experienced charismatic Catholics, there weren’t deep silences in our worship services,” reflects Graham Pulkingham. “There wasn’t a sense of awe or quietness.”

Yet, the cross-fertilization resulted in many Catholics defecting to Protestant churches, beginning in the late 1970s. Many a nondenominational charismatic church today owes at least a third of its membership to disaffected Catholics.

“It caused great problems for the Catholic charismatic leadership,” Synan recalls. “The bishops said you get these people all excited and then they leave. A lot of Catholic charismatics thought their movement would change the church. But it’s never gotten into the Sunday masses. So they gave up, disillusioned, and joined all kinds of Protestant churches, especially nondenominational charismatic ones.”

Doubts About Ecumenism

Ecumenically speaking, the Catholics arrived late—and left early. Despite a spate of prophecies at the Kansas City conference warning against disunity, several denominations withdrew into themselves after 1977 and the ecumenical impetus was lost. Later conferences in New Orleans and Indianapolis tried to recapture this unity, but charismatic Catholics had splintered among themselves in the early 1980s, and things were never the same again.

Presbyterian theologian J. Rodman Williams, who teaches theology at Regent University in Virginia Beach, Virginia, doubts that Catholics were serious about ecumenism: “They’re interested in unity in the sense of us uniting with them; us returning to the mother church. [While] they’ve come a long way since they called us ‘separated brethren,’ one thing that bothers me and others is the increased emphasis put on Mary by the Catholic charismatic renewal. It seems to diminish good relations between us.”

Catholics may not have realized what ecumenism would cost them, but the decision to withdraw from it may have crippled their renewal, Synan believes: “[Pentecostal pioneer David] DuPlessis felt that if you ceased to be ecumenical, you ceased to be charismatic. You dried up. You lost your power.”

“A lot of the Catholic charismatic renewal may be muting its voice to appease the church,” argues church historian Richard Lovelace, “but the Ann Arbor folks [at Word of God] are deeply committed to working with Protestants.” Word of God has included Protestants in its membership and has produced an ecumenical magazine, Pastoral Renewal, recently renamed Faith and Renewal.

Catholic theologian and ecumenist Peter Hocken admits the disunity has agonized Catholics. “Ecumenism is the most difficult area of the renewal for the Catholic church,” he believes. “There aren’t any quick-fix solutions.”

Catholic charismatic renewal, he adds, has roots in “an event that happened to people. [The renewal] is potentially more powerful but also more vulnerable because it’s not a thought-out system of methodology and ideas.”

Evangelical theologian J. I. Packer, who has spoken at Word of God conferences for years, echoes this concern. While he believes Catholic charismatics are closer to Protestants in their theology than is commonly known, he also believes their emphasis on personal experience needs balancing. “It’s a weakness of the renewal,” he says, “to be so experience oriented and so little theologically oriented.”

New Controversies, New Strategies

The 1980s were a decade of slow decline in the Catholic renewal. By 1990, the number of charismatic Catholic prayer groups dropped 23 percent from 6,400 to 5,000. Circulation of the Catholic charismatic magazine New Covenant also declined, prompting its recent sale to the Catholic magazine giant Our Sunday Visitor, Inc. Attendance at Notre Dame conferences leveled off in the eighties at 8,000, and sales of the Life in the Spirit leaders’ manuals dropped. Then, in 1990 and 1991, controversies over authority and teachings rocked some of the charismatic communities. The hardest hit were Word of God and a related community, Servants of Christ the King, in Steubenville, Ohio. Both suffered substantial membership losses and splits among leaders over disagreements that had been simmering for years. Word of God leaders publicly backtracked from many of their apocalyptic positions on world events and publicly repented for exercising too much control over members’ private lives. There were allegations that a misuse of prophetic gifts led to the leaders’ hubris.

“I think a seed entered in,” senior coordinator Ralph Martin told community members in October 1990. “We perhaps took what was prophetic hyperbole and thought it was ‘us.’ We had it all together. We were the best. We were special.”

Ironically, it was Martin who delivered a stunning prophecy beginning with “Mourn and weep, for the body of my son is broken” at the 1977 conference—a prophecy many observers said was a watershed for ecumenical unity.

“We had a special pride in the area of our unity,” Martin says now. “[We felt we had] the recipe for overcoming what the Christian churches experienced through the years. Pride and arrogance got us right in the area of our unity. I believe that is why God is allowing us to experience failure in it right now.”

Leaders in the renewal are also dogged by another problem: Most bishops and priests—key players in renewing parishes—are not charismatic. Renewal leaders have come up with a new approach to persuading them to integrate the renewal into parish life. It comes in the form of a 354-page book, Christian Initiation and Baptism in the Holy Spirit, published in 1991 by theologians Kilian McDonnel and George Montague. The book attempts to prove that spiritual gifts and the baptism in the Spirit were normative in the first eight centuries of the church.

McDonnell claims they have discovered texts in Tertullian, Hilary of Poitiers, Cyril of Jerusalem, John Chrysostom, Basil of Caesarea, Gregory Nazianzus, and several early Syrian theologians who are overtly charismatic. “The baptism in the Spirit doesn’t belong to private piety but to public liturgy,” he believes. “It belongs to the rites of initiation and the Eucharist. It’s not just for special people. It’s normative for the life of the church.”

Several charismatic Protestant theologians have named McDonnell and Montague’s book as the most thought-provoking current work on the renewal. Lovelace, a professor at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, applauded their work and said that some redefinition of the baptism in the Spirit is long overdue. “They’re rewriting Pentecostal theology,” he said.

McDonnell hopes their Catholic scholarship can put a fresh light on the baptism of the Spirit to make it more accessible to those outside the renewal. Not until Spirit-baptism penetrates the institution of the church will the charismatic movement have succeeded as a renewal, he believes.

“The charismatic movement has been looked on as essentially peripheral, a private matter identified with conservatism,” he asserts. “We want the church to appropriate the baptism as her own.”

For the Catholic charismatic renewal to surpass the accomplishments of its first 25 years or move again toward unity with Protestants, much retooling needs to be done. Renewal leaders agree that reflection and refueling is needed; they have titled their twenty-fifth anniversary conference, being held this month in Pittsburgh, as “Return to the Upper Room.” The name refers to more than the first Pentecost: the Catholic renewal began in the upper room of a diocesan center just outside Pittsburgh. How far the effects of that initial gathering will reach in the next 25 years remains to be seen, but Catholic renewal leaders seem convinced that the movement the meeting spawned has not begun to disappear.