Every other night, the shrapnel-scarred S.S. Victory leaves its port in Larnaca, Cyprus, and at a leisurely pace steams southeast for the port of Junieh just north of Beirut and about two kilometers from the famed Casino Lebanon. On this particular night, the captain, a leather-faced Greek who knows the eastern Mediterranean as if it were his own private pond, sets the engines at half-speed and sips from a mug of strong, black coffee.

“Don’t worry, my friend,” he laughs, sensing my uneasiness. “She is a strong ship.”

A few weeks before this voyage, a sister ship took a direct hit. Several crew members and passengers were injured, and one passenger died. Since then, the Victory has sailed to a spot in international waters just out of reach of artillery fire and transferred passengers and cargo to wood-hulled launches. Radar has a harder time reflecting off wooden boats.

A cabin boy—probably 16 years old—stops to chat. He is tall and thin, so I ask him if he plays basketball and then inwardly cringe at my cultural imperialism. “Larry Bird!” he exclaims, his eyes brightening. “He’s my favorite; but I hate Magic Johnson.” We chat for a few minutes about American basketball, and I am amazed that he already knew my very own Detroit Pistons were battling toward a second championship. For a moment, I have forgotten my fear, and we are two strangers in Chicago discussing the NBA.

Too soon, we drop basketball. He wants to know why an American would go to Beirut. I tell him I am a Christian and that I am interested in how Lebanese Christians practice their faith in conditions of war. In this part of the world, it is so much easier to talk about religious belief since everyone in the Middle East belongs to one of the three major faith groups: Christian, Muslim, or Jewish. Belief is assumed, though not always practiced.

The cabin boy laughs too cynically for a boy his age. He tells me I am crazy. He explains that he used to be in one of the militias but was injured and allowed to quit. He shows me a scar on his arm and another on his stomach. Now, he says, he just wants to leave. Would I take his name and when I return to the States, ask our immigration office to let him in?

I begin to explain how private citizens like myself have very little influence on our government, but he interrupts: “I hate this war!” He spits the words at me, then smiles weakly, embarrassed, perhaps, at his emotion. “Keep your head down, my American friend.” He walks down the hallway laughing. It is the last I see of him.

After several days of waiting in Cyprus, I have finally been given permission to enter Beirut. My traveling companion is Leonard Rodgers, who lived in Beirut from 1963 to 1974, then moved back again in 1982 and did relief work during the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. Later that year American missionaries and other U.S. citizens were asked by the U.S. government to leave. Most moved to Cyprus, where they continue to supervise the work of Lebanese associates via radiotelephone. They are a defiant lot, these missionaries to Lebanon. Absolutely forbidden by their mission boards to return to Lebanon, many of them make annual or quarterly visits. In fact, sneaking Americans into the country gives the Lebanese no small measure of satisfaction.

I would soon learn that news of my arrival had triggered a protective network of Christians and Muslims whose only interest is in getting word back to the Western world that the average Lebanese citizen is not a terrorist and, in fact, has a particular fondness for Americans. They remember the days in the 1950s and 1960s when thousands came to “the Paris of the Middle East” to swim, ski, and gamble. And they long for a return to peace and prosperity, believing only America can broker such a deal.

A Dirty Business

Although we have booked sleeping cabins, we spend most of the night in the ship’s dining room, where we talk with the few fellow travelers who sift in and out. Most of those traveling to Beirut these days are agents of the two staples demanded by this civil war’s huge appetite: drugs and money. Drugs keep the boys fighting, and money buys weapons. Drug trading also brings in much-needed hard cash to keep the war machine going. War, Leonard reminds me, is a very dirty business. “There are high-rolling businessmen sunning themselves on the Riviera who last night handed one of these guys a suitcase full of thousand-dollar bills in exchange for a small package of pure heroin,” he explains.

Most of the passengers are men, and when they are not in the dining room, they go to the ship’s casino. Occasionally someone takes out a cellular phone and places a call. A lively conversation, spiced with laughter, follows in Arabic. For four nights I have not slept well, and I am not ashamed to admit it was pure, raw fear that kept me awake. These guys, however—many sporting weapons, and perhaps a few hours from combat—are playing blackjack and calling friends in Beirut where rocket shelling has interrupted regular phone lines.

This cavalier approach to tragedy is important to understand, because it helps illustrate how the church in Lebanon—indeed, how anything in Lebanon—can survive. Despite the nearness of death, the Lebanese know how to live. Within minutes after a seven- or eight-day round of shelling stops, the streets are busy, stores are open, and the entrepreneurial spirit kicks into high gear. Even as the shelling continues, pastors and lay leaders meet in bunkers to plan the next worship service. The moral tragedy is that everyone plays by his or her own rules—or none at all. One of the major challenges for the church is how to return honesty and virtue to the Lebanese moral vocabulary.

Adaptation. Ingenuity. Resourcefulness. Fifteen years of civil war—the most sinister of conflicts pitting like-minded citizens against one another—has exploited both the best and worst of the Lebanese: their will to live and their resolve to avenge even the smallest intrusion on honor and family.

It is in this setting that the church finds itself struggling to survive. Lebanon has seen the gates of hell: artillery fire for days on end at the rate of 20,000 shells a day; drug-crazed teenage militiamen emptying their M-16s and Kalishnikovs on playgrounds, in hotel lobbies, and at busy intersections; gardens booby-trapped with land mines at harvest time in villages where food is scarce; an infrastructure of roads, phones, electricity, water, and sewers shut down for much of the war’s 15 years; hyperinflation worsened by payoffs and protection rackets.

All this in a land where the people were once known for their sophistication, their elan. Once the center of the ancient Phoenician empire, this land was chosen by King Solomon to supply raw materials for his temple. Invading armies have come and gone, but monastery outposts still dot the mountainous landscape, a physical testimony to the 1,600-year presence of the church. The proud steeples can almost be heard to shout: “Battered we may be, but we are still here.” But many wonder if that same cry will be heard at the end of this final decade of the twentieth century. Since 1975, more than 300,000 Christians have left Lebanon; 100,000 live now in the United States.

Christian Versus Christian

At precisely 9:00 on the morning of May 19, I step onto Lebanese soil in the port city of Junieh. We are told that other than the hostages in West Beirut, we are the only American citizens in Lebanon at the time.

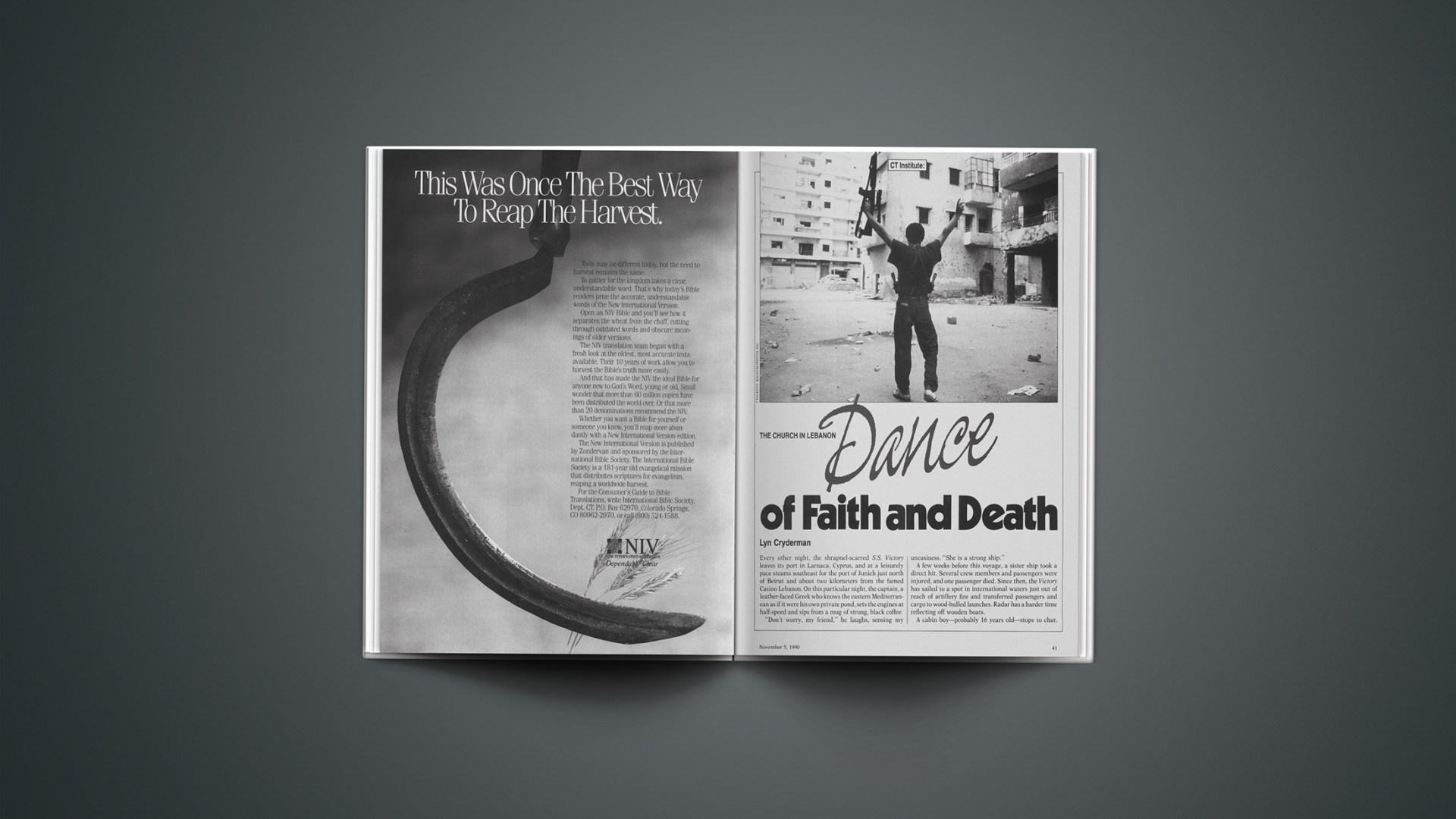

We are also told to be careful. Recent fighting has been the fiercest of the 15-year civil war. Since January 29, more than 1,000 people have been killed, 3,000 wounded, and 300,000 have left the country. Although we arrive during a cease-fire, it is one of hundreds that have been announced and promptly violated. I ask a machine gun-wielding dock worker how long he thinks this one will last, and he just laughs.

The port city of Junieh is controlled by the Lebanese Forces, a private militia loyal to Dr. Samir Geagea. Their enemies for now are members of the Lebanese Army, loyal to Gen. Michel Aoun, who has not left the heavily besieged presidential palace since launching a “war of liberation” last year against the 30,000 Syrian troops occupying Lebanon.

Both men are Maronite Catholics. Both claim to read the Bible daily, to pray, to trust God for strength and wisdom. And it is not hard to find zealous Protestants and evangelicals on both sides of this particular battle who would claim both men are true believers. All of this underscores the difficulty of trying to view the church in Lebanon through Western eyes. For although religion appears to be the driving force behind the years of fighting, one can never be exactly sure where religion ends and culture begins. As historian Michael Hudson wrote in The Precarious Republic, Lebanon is “a collection of traditional communities bound by the mutual understanding that other communities cannot be trusted.” Unfortunately, the glue that holds each of those communities together is a fervent, if politicized, religious faith.

That lack of trust is palpable. Upon entering the heavily fortified bunker that serves as a makeshift immigration office, our interrogators asked us not only our religion, but whether we are loyal to Doctor Geagea or General Aoun. In a Western context, alignment with a particular political party is a matter of personal (and private) conviction. In Lebanon, it could be the difference between life and death. There have been stories of roadblocks set up by Muslims who checked the religious identification card of every citizen who approached. If cardholders were Christian, they were shot. Muslims have been similarly martyred. One of the many factors contributing to this apparently never-ending war is the Arab sense of the propensity to vengeance embedded in the culture of the region. If a Christian village is destroyed by Muslim militia, the only question is how long it will take Christians to respond in kind. That is why allowing Arab leaders to save face is the diplomatic skill of preference for any negotiator assigned to Middle East crises.

I explained to our interrogators that I was not after a political story, but wanted to understand more about Christianity in Lebanon. I soon learned that neutrality is not acceptable in Lebanon, so Leonard and I were placed under the custody of Lebanese Forces Intelligence and politely invited to watch propaganda films for four hours. After that, we were allowed to go, along with a warning that it would not be wise to try to move into any areas controlled by General Aoun.

Beirut and its suburbs stretch about 20 miles along a coastal strip of land approximately 5 miles wide, squeezed between the sea and the mountains. The city itself is divided along the infamous “Green Line” separating East (Christian) from West (Muslim). In both sectors, rival militias control various suburbs, the boundaries changing with each round of fighting. Imagine traveling from the south side of Minneapolis to its northern suburbs, having to stop and show your passport at each suburb’s border. At some border crossings, there are nothing but warning signs, machine gun pillboxes, and a hundred feet of “no man’s land.” Travel across such areas amounts to providing bored soldiers with target practice, which explains why Lebanese have learned to take the longer, more circuitous mountain routes.

The Gospel in a Bomb Shelter

Like most 14-year-old girls, Zena (pronounced Zay-nah) likes to roller-skate, go to the movies (“Patrick Swayze is gorgeous”), listen to rock music (“do you know ‘Wind Beneath My Wings’?”), and talk about boys (“my mommy won’t let me date until I am eighteen!”).

Zena also loves to go to church. “Even if my mommy sleeps in, I get up on Sunday morning and go. And if my church cannot hold services that morning because of damage in the night, I go to another church. Any church.”

Why? “That’s where I learned about Jesus.”

Zena is a child of war. Not once in her lifetime has her country been at peace. Like other Lebanese children, she has learned to tell incoming or outgoing artillery by the sound of the shells passing overhead. She has learned the rhythm of shelling—somehow knowing when it is safe to leave the shelter to play rather than use the time to help restock the bunker before another pounding begins.

Zena has also learned about prayer. One time she was riding with her mother across the Green Line that separates Christian East Beirut from the Muslim West—a barren no man’s land lined with machine-gun nests. As they started to cross, snipers began firing on them. The car bogged down in loose sand and Zena’s mom screamed. “I prayed to Jesus, and we made it across without getting shot,” Zena says in a seriousness that hides her youth.

For almost two years now, Zena has not attended school: the schools are closed, though you can’t fault Lebanese educators for not trying. Earlier this year, 250 children were trapped in a school during 15 days of constant shelling. Parents did not know if their sons and daughters were safe. Food and water were scarce. When the shelling stopped, the principal sent the children home and closed the school.

Though Zena understands, she wishes the schools were open. “It’s boring to have to stay inside all the time. I read or play with my toys, but I would rather go to school.” If the shells are not falling too close to their home, Zena and her parents try to put at least two walls between them and the outside. But when they hear the cluster bombs exploding nearby (devices designed to spray thousands of tiny, razorsharp scraps of metal in every direction, and making a noise much like glass breaking), they go to their underground shelter. Always they are joined by neighbors who do not have shelters. They sit in the semi-darkness and wait.

“Sometimes I read. Sometimes I play cards. But I know Jesus is with me in the shelter.”

By Lyn Cryderman.

Two Naughty Boys

Late in the afternoon, Doctor Geagea’s bodyguard takes us up the mountain to Bekerke, site of the Maronite Patriarchate. The M-16 at my feet and the photograph of the Virgin Mary taped to the dashboard of the Land Rover add to the perpetual dissonance of our surroundings. Here is another one: because we have arrived during the Patriarch’s rest time, I take a short walk along a winding mountain road. About a half-mile from the church grounds, I hear the unmistakable sound of gunfire coming from around a curve just ahead. I leave the road and peer through the brush toward the shooting—only to see a couple of hunters shooting at small birds overhead. Leonard explains that bird hunting is the Lebanese national pastime. After days in a shelter trying to avoid incoming artillery, a cease-fire sends the men and boys into the countryside with shotguns and shooting vests. To a young banker wearing an Orvis vest, I try to point out the irony of innocent birds surviving 15 days of constant shelling, only to fly into a pattern of No. 6 lead shot on their first day of peace. All he can do is smile and say, “I know, I know.”

Back at the patriarchate, we pass some time with the Patriarch’s personal secretary, Michel Awit, who has written several excellent studies of the Gospels that are used in adult Christian education. We learn that it was a phone call from Awit to the Lebanese Forces that allowed us to be released from their custody. When I thank him, he seems a bit embarrassed to be linked so closely to the militia. We are surprised when he tells us he is familiar with CT, but has never been able to subscribe. He taught himself to speak English by reading David Copperfield, and the Gospels through three times.

His scholarly industriousness is not atypical. Most of the schools in Lebanon are sponsored by the churches. In addition to regular small study groups and a fairly popular teaching ministry on Sundays, the Maronites operate numerous elementary and secondary schools. To the basics, they add a strong dose of Maronite doctrine, ensuring political dominance in future generations.

We are soon escorted to a large, narrow room lined with leather chairs and beautiful, ancient tapestries. His Beatitude Nasrallah-Peter Sfeir is a small man, with deep, intense eyes and a ready, though weak, smile. He appears tired, and speaks barely above a whisper. I ask him why two reportedly devout members of his church would take up arms against each other, killing hundreds of civilians in the process. He says they are like “two naughty boys who wanted to get their way.” Then I ask him why the most powerful religious official in the land cannot take the two boys to the woodshed. “I have tried to get them to reconcile, but they do not have ears to hear.”

The Patriarch is much more comfortable talking about how the war has strengthened the faith of his flock. “When the fighting was between Christians and Muslims, our people put their trust in money and houses,” he explains. “But now they see that the fighting may be caused by things deeper than religion. It scares them, and many are turning to God.” Other reports confirm this view. Church attendance is at an all-time high, according to several sources, and the supply of priests in training has church officials encouraged.

The Maronite Catholic Church is the largest Christian body in Lebanon. Slightly less than 500,000 members (17% of the total population) attend one of the 850 parishes in the country. They are clearly the most influential and privileged religious group in modern Lebanon, staunch defenders of a “Christian Lebanon.” They were more or less given a head start in that task when Lebanon declared its independence in 1943. At that time, all religious groups agreed to an unwritten National Pact, which, among other things, divided power according to religious affiliation, with the most power going to the predominant religious group. Thus, the president must always come from the Maronite community, the prime minister from the next most-populous group—Sunni Muslims—and so on. That was fine in 1943, since most agreed that the last official census, taken in 1932, accurately reflected the religious makeup of the country. But by 1975 it was generally recognized that Muslims held a clear majority. With tensions already high over the presence of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, civil war broke out and has continued ever since.

Living It Up At The Hotel Aquarium

The Patriarch provides an elderly driver to take us down the mountain back to Junieh where we drive along the waterfront looking for the hotel with the fewest broken windows. We settle on the Aquarium, a 12-story, modern hotel that once was booked solid with patrons of the nearby Casino Lebanon, but which is currently empty. Again, we are confronted with the incongruities of war. Six young men live in the hotel because they have lost their homes. All can be described as professionals—engineers, bankers, educators—but they have not worked at their professions for several years. Bright, handsome, and articulate, they are perhaps the most tragic victims of the war. “We are finished and we know it,” one of them says with a pathetic smile. He spreads a linen tablecloth on a credenza in the hotel lobby and sets a television on a lamp table beside me. Someone fires up the diesel generator, and with the flick of a switch, Bill Cosby and his TV family entertain us while we wait for the hotel manager to scout out some food.

After dinner, we talk with our new friends until late into the night. They introduce us to a line of conversation we will hear often. “We are Christians. We have lived with our Muslim neighbors for centuries. The problem is with the outsiders. Your nation is Christian. They could stop the fighting here if they wanted to. Why don’t they?”

It is a simplistic argument, and flawed at some levels. But for these average Lebanese Christians, it is their analysis of current reality. They do not understand why fellow believers in the West look to the only Arab Christian nation with either indifference or outright hostility. And they also wonder why American Christians, especially, seem to have more concern for their southern neighbor, Israel.

No Time For Division

Mack Sacco has a message for his Southern Baptist Convention (SBC). He would deliver it personally, but he’s cooling his heels in Larnaca, Cyprus, temporary headquarters of the SBC mission in Lebanon. Mack and his colleagues joined the forced exodus of Americans from Lebanon in 1987, though the Southern Baptists and missionary work of other American-based denominations continues under Lebanese leadership.

Mack speaks Arabic with an Oklahoma accent—sort of like a Gomer Pyle impression of Yasir Arafat. But the Lebanese don’t seem to mind. They love Mack. At least, most of them do. Once, in West Beirut, some Lebanese Muslims kidnaped him, roughed him up, then told him to get ready to die. They had him place his head between his knees and shoved the barrel of a Kalishnikov assault rifle against the base of his skull. “I waited for the shot, but it never came,” Mack recalls. Instead of killing him, they took his wallet, his brand-new tennis racket, and the groceries he had just bought, then drove off in his car.

To the SBC folks back home, Mack has this to say: When you lose sight of your mission, you get sidetracked on all the wrong issues. And then the church can’t do what it was called to do—bring the light of Christ to a darkened world. Since 1948, Southern Baptist missionaries to Lebanon have tried to do just that. They are part of a small cadre of American denominations that began sending missionaries to this region in the middle of the century, ostensibly to reach Muslims. In effect, they represent a second wave of American-inspired evangelistic activity in Lebanon, with the first occurring in the 1890s through efforts associated with the United Presbyterian Church.

Most of the soul winning done by these missions-minded groups could be considered sheep stealing, as the main outreach is to disenchanted members of the ancient or traditional churches (Orthodox and Maronite). “Very little evangelism is done among Muslims in Lebanon,” admits John Sagherian, director of Youth for Christ—Lebanon. “It is not necessarily by design, but simply a reality. For a Muslim to convert to Christianity almost certainly means being disowned by family and friends. In this part of the world, it is dangerous to leave the Muslim faith.”

So YFC and other evangelical groups work primarily with the general population in Christian East Beirut. The chances of a Muslim attending one of the Christian schools where YFC visits is slim. Still, evangelistic work in Lebanon is not easy. “The traditional churches understandably become skeptical of our motives,” Sagherian says. Evangelicals number less than 1 percent of the Christian population, and members of the traditional churches do not always understand why a new church is needed. Sometimes, the evangelicals are confused with cult-like groups like the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Sagherian concedes that sometimes evangelicals working with members of traditional churches amounts to proselytizing. But he does not believe it is always intentional. “One time I was holding a Bible study for a group of new teenaged converts, and one of the boys’ mothers walked in and begged me not to turn her son into a Protestant because they were a strong Maronite family. I told her I just wanted to help him be a good Christian, whether he was Maronite or Protestant. When we have a chance to explain it like that, people are usually very understanding and support our work.”

Still, relations between the newer evangelicals and the traditional churches have been strained. Gabriel Habib is general secretary of the Middle East Council of Churches (MECC). A World Council of Churches-related organization, the MECC has had tremendous success in nurturing ecumenism throughout the Middle East. In fact, they have done something the WCC has been unable to do: In 1988, the Vatican-related Maronites joined the MECC—an unprecedented move in Catholicism.

Habib was the motivating force behind the acceptance of Catholics by the MECC, and he has also taken the lead in improving relations between evangelicals and the traditional churches. One of the concerns the MECC has with evangelicals, he says, is their identification with the West. “If Christianity is to have a witness within the Islamic ethos—particularly in an Arab setting—we must project an image of Christianity that is culturally more authentic,” Habib says. “Increasingly, Muslims see Christianity as a Western religion; therefore, it is the religion of the enemy. I have no problem with the evangelicals’ missionary motivation. In fact, that is quite respectable. But what concerns me is that their sense of history is not great enough. Most of these groups make a huge jump from the early church to the Reformation, ignoring the documented, physical presence of Christianity in this region—often at great sacrifice—for several hundred years. It makes it seem as if they are saying from the day of Pentecost until now, Christianity has never existed, and so now they have to bring it here. In fact, we hear them speak of us as nominal Christians and tell us that because we are not converting people, they will come and do it for us. That seems insensitive to many in the MECC churches.”

Habib says the traditional churches also have a problem with the fragmented nature of evangelicalism. That’s the criticism that really hurts, and Lebanese evangelicals reluctantly admit to a fair degree of factionalism. “I’m afraid some of the pastors have a reputation for not cooperating with each other,” says YFC director Sagherian. The same could be said of the historic relationships within the traditional churches, however, though Habib stresses that the current spirit of unity is absolutely necessary for Christianity to have any credibility with Muslims.

Into Beirut

Finding a driver to make the run across the no man’s land separating the two warring Christian factions is like asking David Duke to deliver phone books in Harlem. But after negotiating, we convince a cab owner to take us across the Dog River as far as the Lebanese army checkpoint, where we hope someone will meet us. Someone turns out to be Elias, a young Lebanese who rushed us to the Contact Resource Center, one of the brightest lights among Christian ministry in Lebanon. Founded in 1977 by the late Dennis Hilgendorf, CRC works primarily with the handicapped victims of the war. Originally affiliated with the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, CRC is now an independent relief-and-rehabilitation ministry, with a U.S. office in Milwaukee. After Hilgendorfs untimely death in 1989, the leadership duties were handed over to Dr. Agnes Wakim, a diminutive Lebanese woman who challenges staff and clients alike to model Christ’s love. Many of the handicapped are Christians who were shot by Muslims. “We tell them they cannot hate the Muslims, that they must forgive them; and we really believe that,” she says.

CRC does not intentionally set out to evangelize Muslims, but because the ministry does not screen patients on the basis of religion, the Muslim community has noticed. “Before we say anything about our faith, we must show the Muslim Christianity in action,” explains Wakim. One of their workers, in fact, is Suha (not her real name), a young Muslim girl paralyzed from the waist down by shrapnel from a bomb. She attends the mandatory devotions, takes her turn reading from the Bible, and occasionally leads a prayer of thanks before group meals. Although her injury came from a Christian attack on her home, she harbors no bitterness. “The bombs come from the leaders on both sides,” she says. “As a Muslim, I am also taught to forgive and to try to live peacefully. And I know the Christian is taught the same thing. If other countries would leave us alone, we could once again live in peace.” I have been told all along by Lebanese Christians that the typical Muslim and Christian have always lived comfortably together. Suha’s presence among a group of Christians begins to add credibility to those statements.

Wakim has invited us to her home in the mountains overlooking Beirut, where approximately 30 Lebanese Christians have gathered. One of them is Lucien Accad, director of the United Bible Society of Lebanon, and one of the leading evangelicals in the nation. Earlier this year, a shell exploded outside his home, crashing a wall down on him. The blast left him deaf in one ear. The next day, a family of five next door was killed. A Church of God (Anderson, Ind.) minister, he could step into the senior pastorate of practically any evangelical church in America and fit right in. And because his wife is Swiss, he could leave at any time. When he spoke at the Lausanne Congress on World Evangelism in Manila, he called Christians living in difficult places around the world to stay and be salt and light. I ask him if he still feels that way.

“I am always tempted to leave. It is just so frightening here. Someone must stay. But I am not sure what to do.” He sounds as if some of his resolve is gone, but in a moment his face brightens as he begins recounting experiences that, to him, confirm his decision to stay.

“People are coming to the Lord every day. Because so many homes have been destroyed, you open your home to whoever needs a place to sleep. Once we had four young men move in with us. They were not believers, and it wasn’t long before I got sick of them. They stayed up all night, keeping us awake, using bad language. It was terrible. Then I remembered the parable of the Good Samaritan. So we tried to be patient. By the time they left, two of the boys came to the Lord.”

He has begun to sound like the Lucien Accad who boldly addressed 4,000 Lausanne delegates in Manila.

“We are discovering more and more that strength comes from praising the Lord. In the past we haven’t been a praising church. But when the shelling begins now, we sing and praise God, and it gives us strength and courage. And we are learning more and more about the parable of the Good Samaritan. We constantly ask ourselves why we are here, and then we just look around us. The problem with most Christians is that we don’t know who our neighbor is.”

Lucien worries that the West—especially America’s evangelical community—has forgotten Lebanon. “How can we blame them, really? We are a small country, and it must seem as if we are trying to self-destruct.”

The younger members of our party disagree. “Mr. Bush could stop this war tomorrow. Your country lets Israel occupy our southern region. You allowed the Syrians to enter and stay. And you sell weapons to both sides.”

It is a crash course on Lebanese culture, its politics, and its religion.

A young architect speaks for all young professionals: “Most of my life I have known nothing but war. I have trained as an architect, but I must work 16 hours a day just to make enough money to get by. It is my generation that suffers the most because we are at the prime of our lives and yet we can do nothing. And unless we know somebody outside, we can’t leave; so we must stay here. The only thing that sustains us is our faith in God. Everything else has failed us.”

An accountant and his wife are expecting their first child any day. They have mixed feelings about bringing a child into the war. “We would leave if we could, but your country will not accept us.”

It is not easy listening, and during a break I walk out onto a balcony overlooking the valley into Beirut. The calm is broken by an occasional explosion and the hum of a hundred thousand generators. From a balcony above and to my right, a voice calls out in the darkness.

“Is this your first time in Lebanon?”

“Yes, and I wish I could stay longer.”

“It was a beautiful country once.”

“It can be beautiful again.”

“I don’t think so.”

The Getaway

Our last day begins with a visit to the headquarters of the National Evangelical Synod of Syria and Lebanon—Lebanon’s Presbyterian Church, which was the fruit of Presbyterian missionary endeavors dating back to the 1820s. The first church was established in Beirut in 1848. Today there are roughly 4,000 members representing approximately 50 churches. Exact figures are hard to come by, but two years ago, there were 60 Presbyterian churches in Lebanon. The exodus is ecumenical, and the synod’s executive secretary, Dr. Salim Sahiouny, is concerned.

“We used to very strongly urge our pastors and members to stay, but what can I tell them? The war drags on, and even the strongest are giving up. They sit in bomb shelters for days on end, and when they come up, their homes are destroyed. How can I tell them to stay?”

Sahiouny also serves as president of the Supreme Council of the Evangelical Community in Syria and Lebanon, of which there are 11 member denominations. Although small in number, the evangelicals have traditionally held a position of influence in Lebanese society. That seems to be changing, as morale in the evangelical community plummets.

“The spirit of our pastors is not so high,” says Sahiouny. “Salaries are nothing, and since our money has been so devalued, what little they earn buys next to nothing. Right now, material needs are the critical issue facing the church. That, and fear. Almost every day I have pastors come to me saying they cannot stay in their neighborhoods because of the militias. These are brave men who simply cannot take it anymore.” As he speaks, two men outside his window are using the cease-fire to fill sandbags.

Generally, the evangelicals are less critical of the American approach to Middle East politics, yet they would like to see American Christians be more understanding of their plight as Arab Christians. “It is our understanding that American Christians tend to be satisfied with their daily lives,” Sahiouny explains. “We feel as if they are not concerned about us.”

Time is running out. Our boat leaves at 5:00 P.M., and there is much to do. On our way to Baabda Palace, we pass within two kilometers of an area where it is generally acknowledged the American hostages are being held. One look across the bleak Green Line into the eerie maze of wrecked buildings and burned-out cars dashes any thoughts that a well-orchestrated commando raid could rescue them.

As we weave our way toward the heavily bunkered palace, I recognize a repeated staccato on car and truck horns and ask Elias, my driver, what it means. He smiles and hits his own horn: ba-da-da-da-DAAAA. It is a rhythmic message that announces loyalty to “The General”: Michel Aoun. When the Syrians invaded in 1989, he barricaded himself in the palace and vowed never to come out until the enemy left. More than 40,000 Lebanese marched to the palace and formed a human barricade around the General’s residence. The General is a popular man in this part of Beirut, but now the shells hitting the palace come from the cannons of his fellow Maronite, Samir Geagea.

My interview with Aoun was arranged by a group of Christians. He is clearly the more popular of the two fighting leaders, but some of the more thoughtful Christians are getting impatient with the power struggle. I am reluctant to go to the palace, knowing that it could keep me from getting out of Lebanon.

We enter the heavily damaged palace and are escorted to a dark inner chamber where the General waits. He is a small man who speaks barely above a whisper. I ask him about his faith, and he tells me his daily time of prayer and Bible reading are important to him. He is careful in his criticism of Doctor Geagea (Geagea does not have the support of the Christians), and he offers to negotiate a peaceful settlement “in the Christian spirit of indulgence and tolerance.” But only on his terms. The General objects to my calling the current conflict a war between Christians, preferring to call it a “war made by Christians for political aims.” He is technically correct.

When the Syrian-brokered Taif Agreement declared the Lebanese government of General Aoun invalid and sponsored the election of Elias Harawi, the Lebanese Forces militia of Doctor Geagea began a frightening bombardment of the palace, ostensibly to chase Aoun from power. As commander of the Lebanese army, General Aoun feels it is his duty to protect all of Lebanon from a political solution that would favor Syria. To preserve Lebanon’s sovereignty, he dissolved the Parliament and thus regards Harawi’s election as invalid. This cease-fire is the longest to date, but both sides are stalemated.

From the palace we race toward the checkpoint at the Dog River, only to learn that we have not been cleared to enter Geagea land. Our boat leaves in 45 minutes, but the soldiers won’t budge.

What occurs next is a fitting finale to this story of a church in a nation of religious people at war. A Christian woman, who must remain anonymous, has accompanied us for just such a situation. She walks up to the command tent and demands to use the phone “to call General Aoun.” I cannot understand what she says, but it works. The officer politely waves us through.

We flag down a passing motorist and persuade him to take us to Junieh in his Mercedes. On our way, he learns we are American Christians and asks if we know Jimmy Swaggart. It is clear he has not heard as much about Swaggart as my cabin boy had heard about the Pistons. Every month, he sends Swaggart a check. “I love that man,” he says as he drops us at the dock.

As I pay an extortionary fare to get out of Lebanon, I recall the words of the gentle Lucien Accad. “Please tell your readers not to forget about us. You will never know how good it makes us feel to know that Christians in America pray for us.”

After a very busy period of ministry in Galilee, Jesus went to the seacoast of Phoenicia (part of which is Lebanon today), whose seaports of Tyre and Sidon were bustling centers of trade. Following the martyrdom of Stephen, some of the Christians moved to Phoenicia for several years. Later we find Paul visiting with believers in Sidon. Christianity is no newcomer to Lebanon.

But to understand the present situation in Lebanon, it is necessary to understand factors that are wholly foreign to Christians in the United States. To us, a church is an association of persons who have grouped together of their own volition. The organization of each church is totally separate from the government of the United States. This is not the case in the Arab world, where Islam predominated for 13 centuries. The Qur’an says the Torah and the Gospels were revealed by God, and their followers must be dealt with accordingly. Over the centuries of Muslim rule, a system developed to put this belief into practice. Under the Ottoman Turks it was known as the “Millet System.”

This system treats Christians and Jews as privileged minorities. They were allowed to exist in Muslim areas as long as they paid a special tax. They could raise their children in their own schools. Each minority community—Maronite, Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and so forth—lived its own life, but was responsible to the ruling power through its leader. Each faith group had its own court system. And at birth, children were registered not as being Lebanese, but as belonging to one of these communities. Thus, each of these religious communities is a nation without territorial boundaries. For example, each Lebanese carries an identity card designating which “nation” he belongs to, thus which religious leader is responsible for his actions, and thus to whom he should owe his allegiance: patriarch, president of the synod, or chief rabbi.

It is within this context that all religious groups in Lebanon must operate. We will begin our brief look at those groups by tracing the origins of the Christian presence in Lebanon.

A Church Divided

In the fourth century, Constantine moved the capital of the Roman Empire to Constantinople. Soon he established a theocracy where it was assumed that all subjects were Christian and that both church and state were branches of one and the same divine government on earth. At this time the area we now call Lebanon was still under the rule of the Roman Empire.

To have one church throughout the empire, there would have to be an agreement on the dogma to be enforced by the emperor. In many parts of the empire, however, there were leaders of substantial groups of Christians who refused to accept the official dogma. These groups are still in existence today, and those in Lebanon include the Gregorian (Armenian) Church, the Syrian Orthodox Church, and the Nestorian Church. Over the centuries these groups were not recognized by the Imperial Church in Constantinople. The churches that were recognized by Constantinople came under the authority of the Five Patriarchates: Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, Rome, and Constantinople. These showed allegiance to the emperor.

Centuries passed, and bitter competition developed between the leadership in Rome and the leadership in Constantinople. By then the patriarchates of Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria were under the rule of Muslim governments, but still kept contacts with the patriarch at Constantinople. In A.D. 1054, the patriarch in Rome decided to break with the other four patriarchs. Congregations loyal to these four patriarchs exist to this day in the Middle East and are known as the Eastern Orthodox churches. They are still organized under the patriarchs of Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria. Eastern Orthodoxy also includes churches under the archbishop of Cyprus and the abbot of Sinai. The Eastern Orthodox patriarchs are considered equals, but when they meet in assembly, the patriarch of Constantinople is considered to be the “first among equals.” Thus the Eastern Orthodox churches have no supreme authority, such as the authority the pope of Rome asserts over the Roman Catholic churches. In Lebanon, the Eastern Orthodox churches make up approximately one-fourth of the Christian population, and about 10 percent of the total population.

One community of Christians in Lebanon stands out numerically over all the others. The Maronite church traces its beginning to the followers of Christ in Antioch—those who were the first to be called “Christians.” At some time, probably during the Persian invasion of the mid-500s, Christians from Antioch and the coastal regions fled into the mountains of Lebanon near Tripoli. Here at Beshara, near the cedars of Lebanon, the Maronite patriarch of Antioch still holds sway over the Maronite church. These people were not conquered during the Arab invasion in the seventh century, nor were they conquered by the Ottoman Turks who overran the area in A.D. 1516—a fact of which they are understandably proud.

Following the Crusades, when the coastal areas were controlled by Western Europeans for nearly two centuries, the Maronites enjoyed a close relationship with the French through Raymond of Tolouse and his successors, who ruled the Latin kingdom of Tripoli. With the recapture of the area by the Arabs around A.D. 1200, the various heads of the Christian communities tried to retain connection with Western rulers. The Maronites succeeded at this, especially in keeping contact with the most powerful ruler in Western Europe—the pope of Rome.

In A.D. 1515, the Maronite patriarch of Antioch accepted the authority of the Roman pope, and thus the Maronites became one of the Uniate churches—churches that acknowledge the authority of Rome but retain their Eastern rites and their liturgies in the old languages. Other Uniate groups in Lebanon are the Greek Catholic, Armenian Catholic, and Syrian Catholic, as well as Christians under the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem.

With the coming of the French Mandate in 1923, one significant change occurred: the Muslims no longer enjoyed the same position they had held under the Arab and Ottoman empires. They now were considered one of the religious nations, or “communities.” At first the two Muslim groups—Sunni and Shi‘a—were considered under one “Higher Council,” as the religious organizations became known. But as the Shi‘ites increased in number and influence, the Higher Shi‘a Islamic Council came into being.

The spread of the nineteenth-century Western missionary movement added still another piece to Lebanon’s religious mosaic. Under the Comity Plan of the International Missionary Council, it was agreed the Presbyterian church would enter Lebanon, while the Congregational church would focus its efforts on Turkey. Between the wars, only one or two other missionary groups began work in Lebanon; but after World War II, more groups, especially from America, sent workers to the region. To be represented before the Lebanese government, and to hold legal title to church property, these groups had to belong to some higher council. What developed became known as the Higher Evangelical Council, under whose umbrella some 11 groups stand as a religious nation. The use of the word evangelical in this sense is quite different from the way the term is used in American churches. In Lebanon, the converts of the early missionaries did not like the derisive term Protestant, which the Catholics and Orthodox groups applied to them. They preferred the word Injiliyya (now translated evangelical). The Arabic word Injil is used in the title of the four Gospels. The Injiliyya, then, would be those who carried the good news, the gospel. Thus the Presbyterian church in Lebanon is officially known as the National Evangelical (Injiliyya) Synod of Syria and Lebanon. It is but one of the 11 “evangelical” churches under the Supreme Council of the Evangelical Community in Syria and Lebanon. Over the years, these “evangelicals” have been integrated into the cultural structure of Lebanon, and the children born to the early converts are registered at birth as belonging to such and such an “Evangelical Community.”

How different it is for us—who consider a church as a group of people freely associating together—to think of churches as political-religious groupings into which one finds himself by fact of birth. And how strange it seems, at least to our American ears, to use the word evangelical to denote those people and institutions that are not Catholic or Orthodox.

A Muslim Majority?

When the last census was taken under the French Mandate in 1932, the official figures showed that 51 percent of the population came under the Christian heading and 49 percent under that of Muslim. Since that time the figures have changed dramatically. One estimate places one-third of the population as Christian, one-third as Sunni Muslim and Druse, and the remaining one-third as Shi’a Muslim.

If it is sometimes difficult for Westerners to grasp the complexities of Lebanon’s Christian community, understanding Lebanon’s Muslims is even more of a challenge. Twenty-four years after the death of Muhammad (A.D. 632), Islam, young and vigorous, faced a critical decision that would bitterly divide it to this day. The first three successors (or “caliphs”) had been elected by close companions of Muhammad. Ali, the son-in-law and nephew of Muhammad, was proclaimed the fourth caliph. His two rivals would not accept Ali’s election and were defeated at a battle near Basrah in Iraq. Ali then set up his capital at Kufah in Iraq. Ali was treacherously killed in A.D. 661 on his way to the mosque in Kufah. Mu’awiyah, the governor of Damascus, assumed the title of caliph and set up the first dynasty of Islam, the ’Umayyid, with its capital at Damascus.

The two sons of Ali, Hasan and Husayn, became the rallying point for an Iraqi party named the Shi’a, or partisans. The spiritual leadership, imamship, through the family of Ali, became as important to the Shi’a creed as the prophethood of Muhammad to the Sunni Muslims. This concept of the imam is the central difference between the two Muslim groups.

Lebanese Shi’a Muslims are located primarily in the country’s southern mountains. Historically, they have had close ties with Iran. Some think they are among the descendants of Persian and Iraqi tribes brought in during the early years of the Muslim occupation to fill the void left by fleeing Byzantines. Though the Shi‘ites agree on the authority of the imam, they are deeply divided as to how many there were before the last one went into a state of occultation, or suspended levitation, to return at some future date. There are those who believe the twelfth imam was the last. These “Twelvers” are strongest in Iran and Iraq and are by far the largest of the Shi’a sects. Another group considers Isma’il, the seventh, as the last imam, and thus they are known as the “Seveners.” They are also known as Isma’ilites. From the Seveners have sprung several other Shi’a sects. These Seveners teach that the Qur’an is only a veil for an inner, esoteric meaning. It must be interpreted allegorically to ascertain religious truth.

In the sixteenth century, the shah of Iran brought many Shi’a teachers from Lebanon. Today, quite a few of the great clerical families of the Shi’a Twelvers have members in both countries. The Iranian government today tries to influence affairs in Lebanon through contacts with Shi’a leaders and by sponsoring extremist groups, such as the Hezbollah.

Sunni Islam, which claims more than 90 percent of Muslims worldwide, bases its beliefs on the Qur’an, the revelation they believe God dictated to Muhammad from the original in heaven. Muhammad is thus the messenger who carries the revelation of God to the world. In this book, God outlines how people should live in their religious, social, economic, and political aspects of life—in fact, in all affairs of life.

Using the Qur’an as the source, Shari’ah law has developed so that a Muslim may ascertain how he may conduct every aspect of his life, according to the will of God. Sunni Muslims worldwide, desiring to do the will of God, seek out Muslim judges to obtain decisions based on this law.

The Druse—a group with Muslim roots (see “The Mysterious Druse,” p. 52)—are fiercely independent and will play the game of politics so as to maintain this independence. The concentration of Druse around the foot of Mount Hermon has played into the hands of the Israelis so as to fend off their bitter enemies, the Sunnis of Syria and the Shi‘ites of Lebanon. They are also concentrated in the mountains behind Beirut and Sidon.

The bitter rivalries between Lebanon’s varied religious groups perpetuate conflict. They stem from an inability to think in terms of a political state in which each religious group is free of the political factor, and in which the political factor is based on a one-person, one-vote ideology.

The concept of being Lebanese is not strong enough to overrule the “I am a Maronite” or “I am a Sunni” sentiment that has been so firmly ingrained into the culture. Even the seats in Parliament are allocated according to religious communities, as are the three highest officials in the land—the president, the prime minister, and the leader of Parliament.

One cries out, “How long, O Lord? How long before peace can come to the people of Lebanon who have suffered so long?”

In the jumble of mountains with their deep ravines that spread out from the base of Mount Hermon are villages peopled, some believe, by descendants of Iranian and Iraqi tribes. These tribes were settled there to fill the void left by the Byzantines who fled the Muslim onslaught in the seventh and eighth centuries.

Early in the ninth century, Darazi, a zealous preacher, along with Hamza, his right-hand man, appeared in these villages. He gathered a close-knit band of men, and together they proclaimed that al-Hakim, a caliph in Cairo, was an emanation from God.

Hamza soon became the proxy for the divine al-Hakim, and his proclamations and the writings of his associates became the fundamental beliefs of the Druse. The Qur’an was not rejected, but it was interpreted as being an outer shell with an inner, esoteric meaning. The Five Pillars of Islam required of all Muslims were abolished, and thus the Druse have been excluded from the fold of Islam.

The Druse have kept their beliefs and their practices to themselves. However, enough manuscripts have fallen into outside hands to gain some insight into their major beliefs. The Druse concept of God is very much like the neo-Platonic one, with various levels emanating from the primal force. The agent of creation seems to be Ali. God and each of the descending beings has an opposer, much as in Manichean thought. There are seven major prophets, among them Adam; Abraham; and Jesus, son of Joseph. Each of these prophets had seven minor prophets, each with 12 disciples. Among these can be found Daniel, Plato, and other biblical and Greek characters. The Druse believe in predestination and in one God, who has manifested himself in human form, the last time being in al-Hakim. They offer protection and mutual aid to other members of the Druse community, and they renounce all forms of Muslim worship.

At the death of Baha al-Din in A.D. 1031, the door to this monotheistic religion was closed. Thereafter, no one was admitted to the Druse fold and no one was permitted to leave. The followers and their descendants became a distinct religious nation from that time on.

The Druse worship in places of seclusion. In fact, all their official gatherings are held in secret. They practice monogamy, though divorce is fairly prevalent. Their belief in transmigration eliminates the need for a concept of heaven and hell. For each soul that dies, another is born; thus, the created number of souls is a constant.

The Druse practice of “dissimulation” makes it difficult to gain knowledge about them. They are encouraged to appear publicly as members of a dominant religion so that they will not be known as Druse. This makes them difficult to distinguish from the Shi’a Muslims of southern Lebanon, the Sunni Muslims of the coastal plains, and even from the Maronites in the southern mountainous reaches. Currently, they reside in the towns and villages of the mountains to the southeast of Beirut and near Sidon, around the base of Mount Hermon just inside the northern border of Israel, and in the Golan Heights.

The Druse are a proud, fiercely independent people. Over the centuries they have maintained their distinctive differences, and have continued as a separate nation despite the repeated upheavals in Syria, Lebanon, and Israel.

By Kenneth L. Crose.