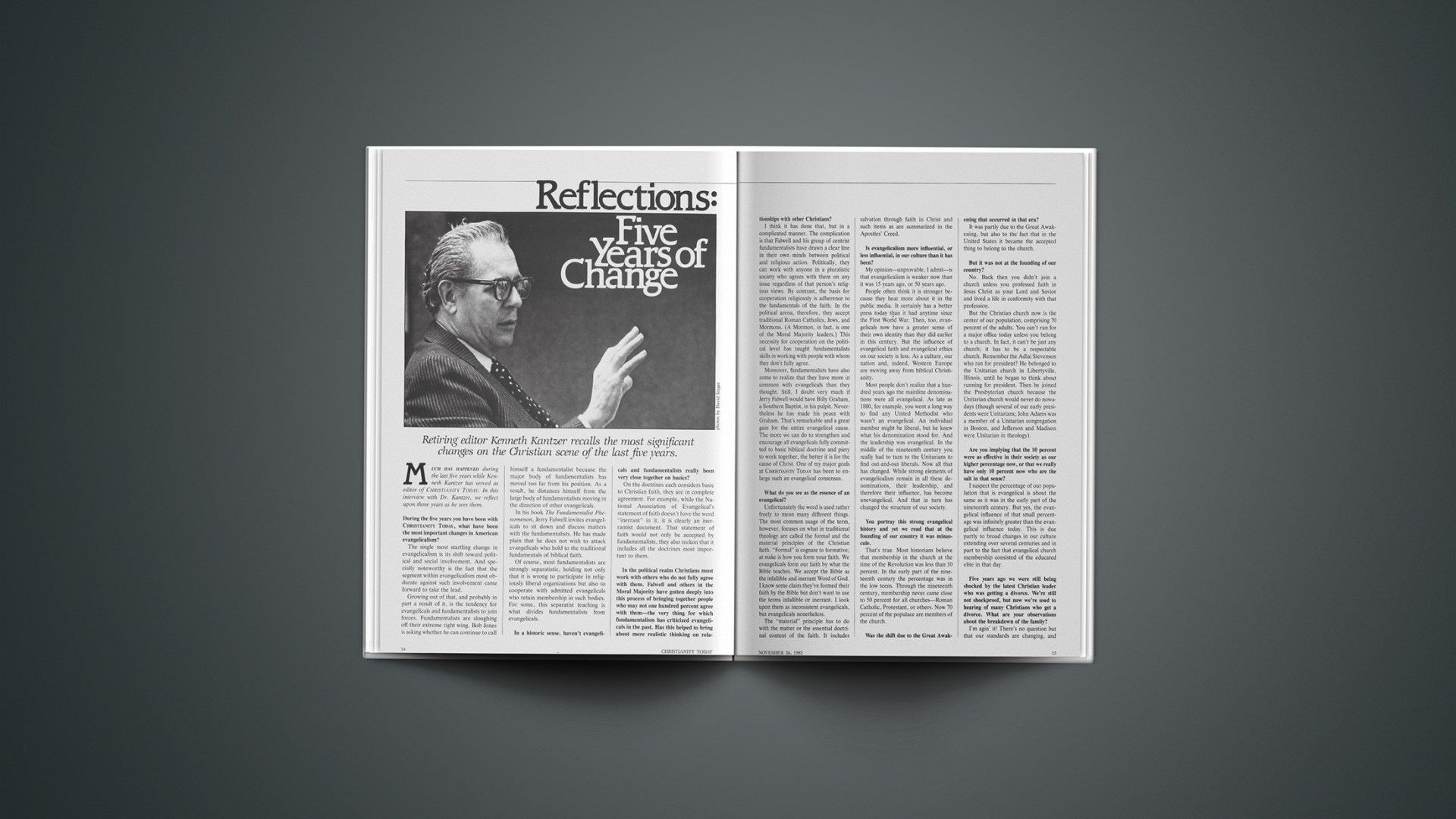

Retiring editor Kenneth Kantzer recalls the most significant changes on the Christian scene of the last five years.

Much has happened during the last five years while Kenneth Kantzer has served as editor of CHRISTIANITY TODAY. In this interview with Dr. Kantzer, we reflect upon those years as he sees them.

During the five years you have been with CHRISTIANITY TODAY, what have been the most important changes in American evangelicalism?

The single most startling change in evangelicalism is its shift toward political and social involvement. And specially noteworthy is the fact that the segment within evangelicalism most obdurate against such involvement came forward to take the lead.

Growing out of that, and probably in part a result of it, is the tendency for evangelicals and fundamentalists to join forces. Fundamentalists are sloughing off their extreme right wing. Bob Jones is asking whether he can continue to call himself a fundamentalist because the major body of fundamentalists has moved too far from his position. As a result, he distances himself from the large body of fundamentalists moving in the direction of other evangelicals.

In his book The Fundamentalist Phenomenon, Jerry Falwell invites evangelicals to sit down and discuss matters with the fundamentalists. He has made plain that he does not wish to attack evangelicals who hold to the traditional fundamentals of biblical faith.

Of course, most fundamentalists are strongly separatistic, holding not only that it is wrong to participate in religiously liberal organizations but also to cooperate with admitted evangelicals who retain membership in such bodies. For some, this separatist teaching is what divides fundamentalists from evangelicals.

In a historic sense, haven’t evangelicals and fundamentalists really been very close together on basics?

On the doctrines each considers basic to Christian faith, they are in complete agreement. For example, while the National Association of Evangelical’s statement of faith doesn’t have the word “inerrant” in it, it is clearly an inerrantist document. That statement of faith would not only be accepted by fundamentalists, they also reckon that it includes all the doctrines most important to them.

In the political realm Christians must work with others who do not fully agree with them. Falwell and others in the Moral Majority have gotten deeply into this process of bringing together people who may not one hundred percent agree with them—the very thing for which fundamentalism has criticized evangelicals in the past. Has this helped to bring about more realistic thinking on relationships with other Christians?

I think it has done that, but in a complicated manner. The complication is that Falwell and his group of centrist fundamentalists have drawn a clear line in their own minds between political and religious action. Politically, they can work with anyone in a pluralistic society who agrees with them on any issue regardless of that person’s religious views. By contrast, the basis for cooperation religiously is adherence to the fundamentals of the faith. In the political arena, therefore, they accept traditional Roman Catholics, Jews, and Mormons. (A Mormon, in fact, is one of the Moral Majority leaders.) This necessity for cooperation on the political level has taught fundamentalists skills in working with people with whom they don’t fully agree.

Moreover, fundamentalists have also come to realize that they have more in common with evangelicals than they thought. Still, I doubt very much if Jerry Falwell would have Billy Graham, a Southern Baptist, in his pulpit. Nevertheless he has made his peace with Graham. That’s remarkable and a great gain for the entire evangelical cause. The more we can do to strengthen and encourage all evangelicals fully committed to basic biblical doctrine and piety to work together, the better it is for the cause of Christ. One of my major goals at CHRISTIANITY TODAY has been to enlarge such an evangelical consensus.

What do you see as the essence of an evangelical?

Unfortunately the word is used rather freely to mean many different things. The most common usage of the term, however, focuses on what in traditional theology are called the formal and the material principles of the Christian faith. “Formal” is cognate to formative; at stake is how you form your faith. We evangelicals form our faith by what the Bible teaches. We accept the Bible as the infallible and inerrant Word of God. I know some claim they’ve formed their faith by the Bible but don’t want to use the terms infallible or inerrant. I look upon them as inconsistent evangelicals, but evangelicals nonetheless.

The “material” principle has to do with the matter or the essential doctrinal content of the faith. It includes salvation through faith in Christ and such items as are summarized in the Apostles’ Creed.

Is evangelicalism more influential, or less influential, in our culture than it has been?

My opinion—unprovable, I admit—is that evangelicalism is weaker now than it was 15 years ago, or 50 years ago.

People often think it is stronger because they hear more about it in the public media. It certainly has a better press today than it had anytime since the First World War. Then, too, evangelicals now have a greater sense of their own identity than they did earlier in this century. But the influence of evangelical faith and evangelical ethics on our society is less. As a culture, our nation and, indeed, Western Europe are moving away from biblical Christianity.

Most people don’t realize that a hundred years ago the mainline denominations were all evangelical. As late as 1880, for example, you went a long way to find any United Methodist who wasn’t an evangelical. An individual member might be liberal, but he knew what his denomination stood for. And the leadership was evangelical. In the middle of the nineteenth century you really had to turn to the Unitarians to find out-and-out liberals. Now all that has changed. While strong elements of evangelicalism remain in all these denominations, their leadership, and therefore their influence, has become unevangelical. And that in turn has changed the structure of our society.

You portray this strong evangelical history and yet we read that at the founding of our country it was minuscule.

That’s true. Most historians believe that membership in the church at the time of the Revolution was less than 10 percent. In the early part of the nineteenth century the percentage was in the low teens. Through the nineteenth century, membership never came close to 50 percent for all churches—Roman Catholic, Protestant, or others. Now 70 percent of the populace are members of the church.

Was the shift due to the Great Awakening that occurred in that era?

It was partly due to the Great Awakening, but also to the fact that in the United States it became the accepted thing to belong to the church.

But it was not at the founding of our country?

No. Back then you didn’t join a church unless you professed faith in Jesus Christ as your Lord and Savior and lived a life in conformity with that profession.

But the Christian church now is the center of our population, comprising 70 percent of the adults. You can’t run for a major office today unless you belong to a church. In fact, it can’t be just any church; it has to be a respectable church. Remember the Adlai Stevenson who ran for president? He belonged to the Unitarian church in Libertyville, Illinois, until he began to think about running for president. Then he joined the Presbyterian church because the Unitarian church would never do nowadays (though several of our early presidents were Unitarians; John Adams was a member of a Unitarian congregation in Boston, and Jefferson and Madison were Unitarian in theology).

Are you implying that the 10 percent were as effective in their society as our higher percentage now, or that we really have only 10 percent now who are the salt in that sense?

I suspect the percentage of our population that is evangelical is about the same as it was in the early part of the nineteenth century. But yes, the evangelical influence of that small percentage was infinitely greater than the evangelical influence today. This is due partly to broad changes in our culture extending over several centuries and in part to the fact that evangelical church membership consisted of the educated elite in that day.

Five years ago we were still being shocked by the latest Christian leader who was getting a divorce. We’re still not shockproof, but now we’re used to hearing of many Christians who get a divorce. What are your observations about the breakdown of the family?

I’m agin’ it! There’s no question but that our standards are changing, and not by any means in just the liberal churches. Our thorough-going evangelical churches are changing, too. I think in part this is a corollary of the fact that 70 percent of the populace are church members. A century ago many of these people would not have been church members. But the situation today also has its good side. The church has got to recognize that it’s not a body of well people. It is under orders from Christ to receive sick people into membership—so long as they are spiritually alive. The church, in fact, is a body of sick people trying to apply to each other the medicines provided by Christ so they may become better and stronger. As our society becomes sicker, we are naturally going to have more sick people in the church.

Are we more biblical in being open and compassionate?

Part of the maturity of a church comes in recognizing that it is a healing body that accepts those who haven’t arrived. But that has got to bring tension, because if you accept those that haven’t arrived, then in the minds of many it isn’t so bad not to have arrived. We’re going to have to live with that kind of problem. Biblical instruction is the key to meeting it. Biblical instruction won’t fully solve it, of course, but it’s the way to tackle the problem. The ideal lifestyle for the Christian must be clearly taught and modeled, but part of that lifestyle is to embrace those who are falling short.

What about the fracas over inspiration?

Five years ago I was fearful that evangelicalism would split into two factions: one with a relatively loose view of biblical authority and the other adhering to a very rigid understanding of biblical inspiration. I think that danger is now receding. Today there is a growing consensus of what I believe to be a more sane understanding of what the church has always meant by the inerrancy and infallibility of Scripture.

On the other hand, those pushing for a looser view of biblical authority have not been able to sway any large segment of the evangelical community in their direction. And some of those on the outer fringe of evangelicalism are beginning to see that things are not so green over on the other side as they had thought. They have discovered that they are not moving out onto a field of broader opportunity but are approaching the edge of a cliff.

How about new movements in the Catholic church?

One of the most significant developments in our time is what has happened in the Roman Catholic church; everybody knows its major outlines. The Catholic church is now becoming like the Protestant church: a mixture of everything. You have traditional Catholics who accept all the dogmas in typical nineteenth-century form including a distinctive Roman Catholic ethics. At the opposite end, you have liberals who are uneasy about believing in God, let alone in a divine Christ.

The charismatic Catholics form a middle group. Here you find the largest number of those we might call evangelical Catholics, who understand the gospel and draw their spiritual guidance directly from the Bible. Charismatic Catholics do not form a neatly evangelical group, however. Some are also traditional Catholics who would like to roll the church back to the nineteenth century. Others are quite pietistic but fairly liberal in their theology. While some feel comfortable in the doctrinal framework of the Roman church, others reject distinctive Roman doctrines or, at best, sit very lightly on them. For all practical purposes they have become Protestants who remain within the Roman Catholic church because it’s a great mission field.

Some see a religious realignment from Catholic versus Protestant to conservative Catholics and Protestants versus liberal Catholics and Protestants. Do you think that is on target?

Yes. That sort of alignment has been evident ever since liberalism struck the Roman Catholic church at the end of the nineteenth century. Roman Catholics have tended to think that liberals are always Protestant liberals. But they are coming to realize that liberals may also be Catholic liberals. Then, of course, both Catholics and evangelical Protestants are fighting the secularism that looms so large and takes so many different forms today. In self-protection, therefore, conservative Catholics have pulled together with conservative Protestants against common enemies.

What changes do you see on the international scene?

In the last five years the leadership of the church has shifted dramatically from the missionary to Third World nationals. No more than ten years ago, control of the overseas mission lay in the hands of the North American missionary—or worse, in the mission headquarters at a continent’s distance from the field. But today leadership has transferred to the national church. The missionaries are there with resources, education, finances, and particular skills. But they aren’t running the show; they’re waiting until the national church tells them where they can function.

Of course, this has created all sorts of problems. But it has also brought immense good. One side effect is that the new Third World leadership is touchy about doing things the North American way. It has to prove that behind the scenes missionaries are not pulling the strings, but that they themselves are exercising genuine independent leadership.

What do you feel will be the results of this theologically 25 or 50 years down the road? Do you see distinct African and Asian theologies emerging?

When Christianity penetrates an established society, all sorts of new sects spring up. That has proved true in the United States even though American churches are European churches made up of descendents of Europeans. Yet native American sects sprang up. We have our Mormons, our Jehovah’s Witnesses, and especially in Southern California, our 750 varieties of heresy. But all the major denominations remain basically orthodox in their official confessions of faith.

The church in Africa also will surely be molded by its African heritage. But in Africa and Asia, the local homegrown heresies and sects will be multiplied because there the church is adapting to alien cultures. In time, it will develop a more mature and consistent African or Asian theology, and some of the oddities around the fringe will disappear. On the other hand, we who stand more solidly in the stream of Western Christianity cannot reject out of hand the possibility of learning new truth from the Third World churches. God is always free to shed new light on his Word, and we must beware of the pride that closes our minds to fresh insights that can enlarge our understanding of God and his world.

Mainline denominations overseas tend to be relatively conservative, and there is broader acceptance of the ecumenical agenda. Do you see that as changing?

Overseas churches are both more conservative and more ecumenical. That sounds contradictory, doesn’t it? It certainly doesn’t follow our pattern in the West where the more conservative a church is, the less it is likely to be interested in the ecumenical movement. But what seems odd to us in the West makes good sense from the viewpoint of the mission field. Missionaries tend to represent the theologically conservative element in the mainline denominations, and therefore daughter churches tend to be more conservative. At the same time, the mother church is perceived differently by the Third World churches for they tend to see it as reflected in the conservative missionaries. Also, small differences in doctrine don’t seem quite so important in the midst of a pagan society where the church is struggling for its very existence. National churches, therefore, are generally more open to ecumenical movement and less critical of some things that bother us very much. But eventually, I believe they will have to come to grips with the same sort of problems we have had to face.

Do you believe the World Evangelical Fellowship (WEF) and the Lausanne Committee will merge fairly soon?

I think that’s a foregone conclusion. WEF has tied together evangelicals around the world, but it’s been dominated by the Third World group. David Howard’s election as general secretary and the move of the WEF offices to the NAE building are symbolic of what’s going to happen. Perhaps WEF would have preferred a Third Worlder as general secretary, but Howard is very capable and highly trusted by almost everyone. Third World leaders revere Billy Graham and respect NAE. But they don’t want to be told what to do.

In any case, David Howard’s election and the move of WEF to the NAE office building are significant straws in the wind. Both worlds will profit. We can contribute resources and experience to the Third World churches; they, in turn, have much to offer us. There are some very bright Third World leaders around the world. They know what needs to be done, and they are not bashful in saying what they have to say. We can learn much from them.

How do you view the Third World tension between liberation theology and evangelicals? Do you see a healthy intermixing of major dangers?

Let me back up a bit in answering that question. Throughout the entire nineteenth century, evangelicals (especially Puritan evangelicals) were involved in all sorts of social causes. In some ways Prohibition represented the high-water mark of evangelical and Puritan impact on American morals. But when Prohibition failed, evangelicals felt the bottom had dropped out. They had fought for a cause and lost. At the same time they were squeezed out of leadership roles and places of influence in all the major old-line denominations and religious institutions. Their response was to wash their hands of involvement in political and social activity. My father-in-law, a wonderful Christian man, never voted in his life—for conscience’ sake. He didn’t want to waste his time and energies in a fruitless endeavor. His reaction may have been extreme, but it was a reflection of the attitude of many evangelicals from 1920 through 1960. I think the current tendency of evangelicals to move back into social and political action is good. Of course, it also opens the door to many dangers, but basically I think it means we are simply being Christian in our society. After all, our Lord commanded us to be salt to the earth.

Do you see the socially involved Third World leaders maintaining their orthodoxy theologically?

Yes, I do. And influencing Americans along the direction in which the American church is beginning once again to move. Of course, not all are evangelical. I understand and sympathize with the so-called liberation theologians even though I heartily disapprove of their attempts to synthesize biblical Christianity and Marxism. Fifteen years ago in Chile, it was really very, very difficult to maintain a Christian conscience, with a proper regard for humanity, and not want to be a revolutionary. The same is true today in many other parts of the world. Evangelical concern about human justice, human dignity, and basic human rights (including the rights of the unborn) is growing and so is the determination to do something about these matters.

The June consultation on the Relationship between Evangelism and Social Responsibility, sponsored by WEF and the Lausanne Committee, was a major move in the right direction. The sponsors chose the participants wisely. They included not just Third World and mission leaders who would politely agree with one another. They brought in those with sharp edges in their thinking in the hope that evangelicals could find common agreement while still protecting those sharp edges so important to each.

And it happened! By no means were evangelicals as far apart as some had thought. Art Johnston didn’t really think all social action is bound to be sinful. And Ron Sider never did believe the gospel is primarily trying to improve the society in which you live. Grand Rapids was a significant milestone for the evangelical cause. John Stott, with a great deal of help from others, wrote the resulting statement, and it’s a remarkably balanced document.

How do you feel about parachurch organizations?

On the whole I’m sympathetic with parachurch organizations. After all, CHRISTIANITY TODAY is one.

Parachurch structures are usually set up by individual Christians to do what denominations or the local churches have been unable to do. While I would prefer to have such structures directly accountable to the churches, I am grateful that they are doing a job that wasn’t getting done. So I’m willing to put up with poor control that leaves possibilities for any wild-eyed person to do almost anything. Parachurch organizations are getting good things done. And I don’t see any diminishing of the parachurch role in the foreseeable future.

Another recent phenomenon has been the electronic church.

I have mixed feelings about the electronic church. I know the common charge that they are speaking only to themselves. To a considerable extent they are talking only to people who already agree with them and their theology. But that’s not all bad. The saints need instruction and exhortation, too. My own father, though a professing Christian all his life, first found a really vital faith and living hope in Christ by listening to a radio preacher—and not the best one at that.

But the electronic church also reaches a great many who aren’t churched, and so it is an effective evangelistic tool. My grandmother (my mother’s mother) for the first 70 years of her life adhered faithfully to the religion of good “Americanism”: Do your best and in the end everything will come out all right. Then she began listening over the radio to the gravelly voice of Dr. M. R. DeHaan. Through his “electronic church” she came into a wonderful acquaintance with Jesus Christ, the Lord and Savior of sinners.

The bad part of the electronic church is that it often fosters a private Christianity with no obligation to others. This denies a fundamental aspect of Christian faith: We are a body—a body of human beings united in Christ. All too often the electronic church encourages people to warp biblical Christianity out of shape by turning it into a privatized faith. Yet some in the electronic church do encourage their viewers to get involved in local churches. As a result, many have done so.

Of course, vigorous objections against the electronic church are also raised because it drains money from other Christian organizations. It is true that Christians are contributing hundreds of millions of dollars to the electronic church. We cannot help but wonder if those same resources wouldn’t produce immensely greater benefits in the long run if channeled into colleges, seminaries, missions, and evangelism through the local church. Yet relative values like these are hard to assess. And who can set the price of a soul’s salvation?

How do you assess the boom in Protestant elementary and secondary schools?

Oddly, just at the time the Catholic church is abandoning its schools, Protestants are starting them. Are we evangelicals Johnny-come-latelys or just perverse? I think there is a valid explanation for this dramatic reversal. The Catholic church is becoming more like the populace; it has become Americanized. When someone runs for Congress, you don’t ask if he’s a Roman Catholic—but 20 or 30 years ago you did. Remember the John Kennedy campaign? Today Roman Catholics are an accepted part of society, so separate schools are not as important to them. That’s why they are no longer willing to lay out the immense amounts of money necessary to finance private schools.

Though they don’t realize it, in the past evangelicals greatly influenced what our schools were like. It was the King James Bible that was read in most schools throughout our land. When prayers were offered they may not have been good, warm, evangelical prayers, but they were influenced by the evangelical tradition. The schools also cooperated with evangelical churches. But with the decline in evangelical influence upon our society, and with the shift in mainline religious leadership away from evangelicalism, evangelicals now sense keenly their minority position. They want to educate their children in schools where they can protect their evangelical heritage, which is now under greater pressure than it was even 20 years ago.

The 1962 Supreme Court decision that barred the Board of Regents from formulating a prayer for New York schools triggered the boom. In the minds of many, that ruling eliminated prayer from our public schools. Of course, the decision didn’t really do that, but that’s the way many interpreted it. According to the popular version, it pushed God out of our public schools. Certainly that decision had tremendous impact in encouraging people to start schools.

Incidentally, the charge that private schools were started to foster racism is a red herring. Such schools were infinitesimal, and the great growth of private schools has come primarily because of the desire for Christian education, and secondly, to secure a better quality of education than public schools provided.

What overall quality of education are these kids getting?

On the whole, students in private schools do better on their standardized tests than students in the public schools. Part of the explanation is that they’re a somewhat select group of children with better-heeled and better-educated parents. But that doesn’t explain the significant improvement in test scores for students who transfer from public to private schools. More important is the fact that most who patronize these private schools want their children to learn the three Rs. They don’t look upon school as just a baby-sitting affair or a state requirement. Across the board, private schools are doing the better academic job. What they lack is a great many fringe benefits that cost a lot of money. But some of these, such as music programs and sports, have been curtailed or dropped in some public school districts for lack of funds.

How are our Christian colleges faring?

Many Christian liberal arts colleges are cutting back in quality in order to survive. In my judgment this is tragic since we mortgage the church of the future by providing poor quality college training for our youngsters. I recognize that if Christian people don’t support them, they have to do something. And I deeply regret that evangelicals don’t see the importance of Christian college education. To me, that should be one of the great priorities of the evangelical movement. But it isn’t.

How are we going to finance Christian higher education in view of the staggering costs projected for the decade ahead?

Unless we make a radical change in educational finances, more and more of our students will have no choice but to go to state schools. Some find an easy solution to all our financial troubles in government subsidies. But the old adage is still true: he who pays the piper calls the tune. Unless we can find a way for government to support higher education without controlling its educational philosophy, government supports would prove a curse instead of a blessing.

Most agree that the kind of governmental aid showing most promise is that of indirect grants to students who then would be free to choose their own schools—public or private. Such aid is now available and it does not seem as yet to have brought excessive governmental control. But it needs to be greatly expanded if private colleges are to compete on an equal basis with our public universities.

Do you think more support from the churches is feasible?

By all means! Academic institutions can never support themselves adequately. Even in the unlikely possiblity that indirect government aid to students increases significantly, our Christian institutions will continue to need heavy support. And few evangelical investments could ever bring greater spiritual profit to our churches.

You are personally very much interested in seminary education. What has happened there in the last five years?

Evangelical seminaries continue to grow in size and influence. They are now pouring graduates into the churches in sufficient number to change the whole complexion of the North American clergy. The most conservative and most thoroughly evangelical ministers in the United States are to be found in the under-30 crowd.

Have you changed in the last five years?

I’ve changed in some superficial ways. I’m immensely more conscious about my vocabulary when I write. I strive for a fog index of ten [tenth grade]. If I move back into writing theology, I wonder how my colleagues will respond to theological articles written at that level.

How do you think these five years may have changed the impact of your ministry for the balance of your life?

Six years ago my goal was to get out of administration so I could bury myself in a library and spend the rest of my life writing a systematic theology and erudite books on theology and related topics. As editor of CHRISTIANITY TODAY, I’ve written for a wholly different kind of reader.

Do you think this will make you more or less effective?

I shall be less effective with professional theologians. I have held serious administrative posts for over 30 years, and I have always given them my best. I am now 65. At my age it is physically impossible to pick up what I might well have been able to pick up six or more years ago. In a way, therefore, my stint at editing CHRISTIANITY TODAY is responsible for a redirecting of my life. I now plan to write primarily for the pastor and the lay person—the same person I’ve been writing for in my CHRISTIANITY TODAY editorials.

Do you feel this is for the good?

Only God knows the answer to that. I think it’s wise for me, given the factors that have molded me across the years. I certainly have no regrets. I teach others that Christians should be servants available for whatever ministries Christ has for them. So I’d better practice what I preach.

If you could remain out there leading the troops, where would you take Christianity and CHRISTIANITY TODAY in the next five years?

CHRISTIANITY TODAY should be a flagship. It should carry the evangelical banner high for all to see. And in setting forth the evangelical faith it should avoid the temptation to settle for a tasteless pabulum concocted from the least-common denominator of all who call themselves evangelical. It should hold forth a full-blooded Christianity. Only thus can evangelicalism be seen for what it really is—an exciting, gutsy faith important for living on planet Earth, and beautifully attractive to the needy soul. Only thus can it serve as a rallying point for evangelicals of all sorts. From time to time, of course, evangelicals will disagree with the articles published in its pages and even with its editorials. But CHRISTIANITY TODAY ought to be the kind of magazine with which the broad spectrum of evangelicals can identify. They need to be able to say: “That’s my magazine. On the basics it represents my kind of Christianity. It faithfully sets forth a truly biblical Christianity, and it does so with honesty and vitality. It makes mistakes, as we all do, but it’s headed in the right direction.” CHRISTIANITY TODAY should carry the flag for biblical evangelicalism.

But CHRISTIANITY TODAY has an even more important role than serving as the flagship of evangelicalism. It is to create an effective leadership for the church of Christ. The evangelical church today desperately needs good leaders. By contrast with the nonevangelical churches, our leadership is not educated. We have zeal and commitment, but we are not well trained with skills for effective leadership. We surrendered that in the early part of this century, and we’re now living in the shadow of that defeat. No doubt, if we had to choose between spiritually committed leaders with zeal for Christ’s kingdom and educated leaders well equipped for their tasks, we should without hesitation choose the former. But neither alone is adequate. Both are essential if the church of Christ is not to suffer.

In the decade ahead, I believe CHRISTIANITY TODAY’S major role is to help equip leadership for the evangelical churches. It must do this in many different ways. Most evangelicals, including its leadership, haven’t really thought through their evangelicalism. The evangelical lay person can’t define evangelical teaching with precision. He certainly can’t articulate biblical doctrines with clarity; sometimes he can’t even list them. Therefore biblical and evangelical teaching do not really shape his ongoing lifestyle and daily thinking. They don’t determine how he reacts when he reads the newspaper or carries on his daily business or pulls the lever in his polling booth or writes his monthly checks to spend his income. CHRISTIANITY TODAY must provide Christian leaders with resources to enable him to shape his conscience. We have no right to play God. But we do have full warrant to explicate the Word of God and what it means to think Christianly according to the Scripture and what it means to live out the Christian life in our world in obedience to the Lord of the church.

CHRISTIANITY TODAY is in an exceptional position to carry out this task. When it was launched, nobody knew what CHRISTIANITY TODAY would amount to, and many were quite suspicious of it. Thorough-going evangelicals were grateful for it, but didn’t realize how influential it was to become. Now we know that three times as many minsiters read it and look to it for leadership as any other magazine. That’s why I have reckoned it a great privilege to be its editor. And that’s why a heavy responsibility lays upon Dr. V. Gilbert Beers, its new editor. He needs the earnest prayers of all of us.