MARC issues the twelfth edition of its mission handbook.

The North American overseas missionary force is growing at an adjusted annual rate of 6.8 percent—almost three times that of the United States population. But financial support in real terms (adjusted for inflation) grew only half as fast, at an annual rate of 3.4 percent. These strong vital signs emerged as the missionary enterprise based on this continent got a reading on its pulse for the first time in four years.

This encouraging overall picture emerged from a study of the twelfth edition of the Mission Handbook, due for distribution early next month. Prepared and edited by the Missions Advanced Research and Communication Center (MARC), a division of World Vision International, the handbook has earned its niche as the directory and statistical sourcebook in its field: North American Protestant ministries overseas. The new edition documents the shifts that have occurred since the 1975 survey (on which the eleventh edition was based) and late 1979, when mission agencies were surveyed for tabulation in the new volume.

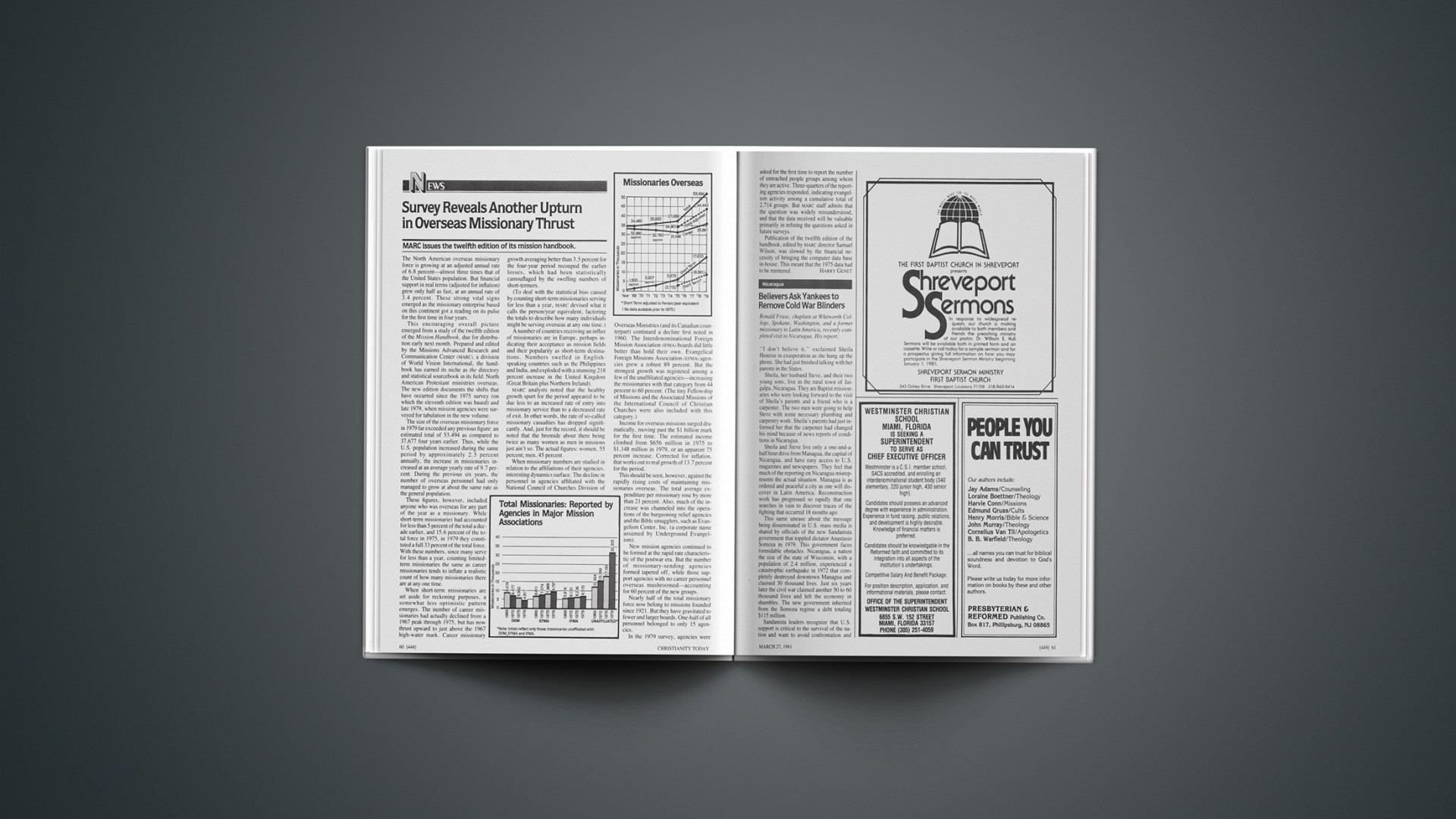

The size of the overseas missionary force in 1979 far exceeded any previous figure: an estimated total of 53,494 as compared to 37,677 four years earlier. Thus, while the U.S. population increased during the same period by approximately 2.3 percent annually, the increase in missionaries increased at an average yearly rate of 9.7 percent. During the previous six years, the number of overseas personnel had only managed to grow at about the same rate as the general population.

These figures, however, included anyone who was overseas for any part of the year as a missionary. While short-term missionaries had accounted for less than 5 percent of the total a decade earlier, and 15.6 percent of the total force in 1975, in 1979 they constituted a full 33 percent of the total force. With these numbers, since many serve for less than a year, counting limited-term missionaries the same as career missionaries tends to inflate a realistic count of how many missionaries there are at any one time.

When short-term missionaries are set aside for reckoning purposes, a somewhat less optimistic pattern emerges. The number of career missionaries had actually declined from a 1967 peak through 1975, but has now thrust upward to just above the 1967 high-water mark. Career missionary growth averaging better than 3.5 percent for the four-year period recouped the earlier losses, which had been statistically camouflaged by the swelling numbers of short-termers.

(To deal with the statistical bias caused by counting short-term missionaries serving for less than a year, MARC devised what it calls the person/year equivalent, factoring the totals to describe how many individuals might be serving overseas at any one time.)

A number of countries receiving an influx of missionaries are in Europe, perhaps indicating their acceptance as mission fields and their popularity as short-term destinations. Numbers swelled in English-speaking countries such as the Philippines and India, and exploded with a stunning 218 percent increase in the United Kingdom (Great Britain plus Northern Ireland).

MARC analysts noted that the healthy growth spurt for the period appeared to be due less to an increased rate of entry into missionary service than to a decreased rate of exit. In other words, the rate of so-called missionary casualties has dropped significantly. And, just for the record, it should be noted that the bromide about there being twice as many women as men in missions just ain’t so. The actual figures: women, 55 percent; men, 45 percent.

When missionary numbers are studied in relation to the affiliations of their agencies, interesting dynamics surface. The decline in personnel in agencies affiliated with the National Council of Churches Division of Overseas Ministries (and its Canadian counterpart) continued a decline first noted in 1960. The Interdenominational Foreign Mission Association (IFMA) boards did little better than hold their own. Evangelical Foreign Missions Association (EFMA) agencies grew a robust 89 percent. But the strongest growth was registered among a few of the unaffiliated agencies—increasing the missionaries with that category from 44 percent to 60 percent. (The tiny Fellowship of Missions and the Associated Missions of the International Council of Christian Churches were also included with this category.)

Income for overseas missions surged dramatically, moving past the $1 billion mark for the first time. The estimated income climbed from $656 million in 1975 to $1,148 million in 1979, or an apparent 75 percent increase. Corrected for inflation, that works out to real growth of 13.7 percent for the period.

This should be seen, however, against the rapidly rising costs of maintaining missionaries overseas. The total average expenditure per missionary rose by more than 21 percent. Also, much of the increase was channeled into the operations of the burgeoning relief agencies and the Bible smugglers, such as Evangelism Center. Inc. (a corporate name assumed by Underground Evangelism).

New mission agencies continued to be formed at the rapid rate characteristic of the postwar era. But the number of missionary-sending agencies formed tapered off, while those support agencies with no career personnel overseas mushroomed—accounting for 60 percent of the new groups.

Nearly half of the total missionary force now belong to missions founded since 1921. But they have gravitated to fewer and larger boards. One-half of all personnel belonged to only 15 agencies.

In the 1979 survey, agencies were asked for the first time to report the number of unreached people groups among whom they are active. Three-quarters of the reporting agencies responded, indicating evangelism activity among a cumulative total of 2,714 groups. But MARC staff admits that the question was widely misunderstood, and that the data received will be valuable primarily in refining the questions asked in future surveys.

Publication of the twelfth edition of the handbook, edited by MARC director Samuel Wilson, was slowed by the financial necessity of bringing the computer data base in-house. This meant that the 1975 data had to be reentered.

Nicaragua

Believers Ask Yankees To Remove Cold War Blinders

Ronald Frase, chaplain at Whitworth College, Spokane, Washington, and a former missionary to Latin America, recently completed visit to Nicaragua. His report:

“I don’t believe it,” exclaimed Sheila Heneise in exasperation as she hung up the phone. She had just finished talking with her parents in the States.

Sheila, her husband Steve, and their two young sons, live in the rural town of Juigalpa, Nicaragua. They are Baptist missionaries who were looking forward to the visit of Sheila’s parents and a friend who is a carpenter. The two men were going to help Steve with some necessary plumbing and carpentry work. Sheila’s parents had just informed her that the carpenter had changed his mind because of news reports of conditions in Nicaragua.

Sheila and Steve live only a one-and-a-half hour drive from Managua, the capital of Nicaragua, and have easy access to U.S. magazines and newspapers. They feel that much of the reporting on Nicaragua misrepresents the actual situation. Managua is as ordered and peaceful a city as one will discover in Latin America. Reconstruction work has progressed so rapidly that one searches in vain to discover traces of the fighting that occurred 18 months ago.

This same unease about the message being disseminated in U.S. mass media is shared by officials of the new Sandanista government that toppled dictator Anastasio Somoza in 1979. This government faces formidable obstacles. Nicaragua, a nation the size of the state of Wisconsin, with a population of 2.4 million, experienced a catastrophic earthquake in 1972 that completely destroyed downtown Managua and claimed 30 thousand fives. Just six years later the civil war claimed another 50 to 60 thousand lives and left the economy in shambles. The new government inherited from the Somoza regime a debt totaling $115 million.

Sandanista leaders recognize that U.S. support is critical to the survival of the nation and want to avoid confrontation and isolation at all costs. In an interview, Carlos Chamorro Coronel, chief of the cabinet for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, expressed this concern by displaying some clippings from the U.S. press which, in his view, significantly distorted events and reflected an alarmingly hostile attitude.

Many Nicaraguans believe the strategy of the new administration in Washington is to identify Nicaragua as a lackey of Russia and Cuba and as a principal conduit of arms to the rebels of El Salvador. It therefore discredits the revolution by implying that the present government has sold out to Communism and that it is only a matter of time before Nicaragua becomes a totalitarian state that will suppress freedom even more effectively than Somoza did. This strategy, if it succeeds, will justify cutting off U.S. aid to Nicaragua and force it into the arms of the Soviet Union, repeating the Cuban scenario of 20 years ago.

Such charges frustrate Nicaraguans on at least two scores. First, the Nicaraguan revolution, unlike the Cuban one, has a strong Christian presence. Chamorro declared that he is not a Sandanista, although he actively supported their struggle, and that he is not a Marxist but a Christian. He recognizes the presence of Marxism in the government but said, “I believe that the revolution is more a Christian revolution than a Marxist revolution.” He went on to explain that Nicaraguan Christians do not share the North American fear of Marxism. The nine-member Sandinista directorate, the real power behind the five-man governing junta, published an official communique on religion last October 7. It stated that religious freedom is “an inalienable human right guaranteed by the government” and recognizes the right to propagate one’s religious belief publicly.

Nicaraguans also resent the implication that the revolution has been “stolen” by a small, elite group of radicals. The revolution, they argue, was a popular uprising that witnessed the participation of virtually the entire population and is fiercely nationalistic. The new government will remain friendly to Cuba, and to the rebels in El Salvador who have strongly supported its struggle, but it will chart its own course.

(Nicaragua’s Sandinista leadership has been closely linked to the flow of arms to Salvadoran guerrillas. One member, Bayardo Arce Castaño, has been singled out as particularly involved.—Ed. note)

Opposition press, radio, and political parties function in Nicaragua, but the very strong presence of the Sandinistas has raised fears about the future of pluralism. Chamorro says that a strong military organization is required because the neighboring governments are not friendly and harbor approximately six thousand of Somoza’s national guard who fled there after the revolution.

On the morning of Chamorro’s interview, word was received in his office that six Nicaraguan soldiers had been ambushed on the Honduran frontier by ex-guardia.Chamorro pointed out that the young North American colonies created a militia for protection against Indians and the British. He expressed the opinion that the U.S. can afford a great deal of pluralism today because its government is so strong that no internal group even dreams of overthrowing it. He argued that this has not been the case in Latin America, and that as the new government becomes stronger and more secure, the degree of pluralism will increase.

Chamorro admitted that elements of the private sector had become disenchanted with the new government because it had consciously chosen “the option of the poor.” The old elite had lost its position of privilege and was faced with the prospect of paying taxes it had avoided under Somoza. The government had cut rents in half and placed curbs on profits. The Nicaraguan business community still controls about 60 percent of the economy, and Chamorro made clear that the junta intends to support a market economy, allocating 64 percent of the long-delayed U.S. loan to the private sector.

Frustration over the image of Nicaragua being projected in the U.S. mass media is shared by many sectors of the evangelical community, which supports the new government with varying degrees of commitment. The annual convention of the Nicaraguan Baptist Church, meeting in late January, invited one of the Sandinista comandantes to address a session. He spoke in a forthright manner and the messengers (delegates) appeared satisfied with his answers.

Many pastors and lay people are actively supporting the process of national reconstruction made necessary by the devastation of the civil war. Gustavo Parajon, a U.S.-educated medical doctor and Baptist layman, has played a critical role as founder of the interdenominational Evangelical Committee for Help and Development, CEPAD, an organization created in response to the 1972 earthquake. During the civil war it organized refugee centers across the country, with food, medicine, and shelter.

The current CEPAD director is Baptist layman Gilberto Aguirre. He explained that he supports the new government because it has made the poor its first priority and has taken concrete measures to improve their lot. He referred to the rent reduction and pointed out that food is cheaper in Nicaragua than in any other Central American country, and that education is free at all levels. The government also has sponsored a massive literacy campaign that saw many evangelical young people move into remote rural areas for several months as teachers. The presence of the gospel in Nicaragua today is seen in Scripture verses and slogans on walls, billboards, and public buses. One such billboard promoting the literacy campaign showed a young boy writing a letter: “Jesus, I can write your name.”

Aguirre is also a member of the National Commission on the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights. He points with pride to the restraint the Sandinistas have demonstrated toward the captured members of Somoza’s National Guard, deeply hated for their indiscriminate lawlessness. He acknowledges that there were some regrettable human rights violations in the days immediately following Somoza’s defeat. But it is remarkable that they were not more widespread. In December, in honor of the United Nations Human Rights Day, 503 prisoners were released; 200 more are to be released soon. Both the International Commission of Jurists and Amnesty International give the government high marks for its human rights record.

Aguirre believes the government’s policies are designed to secure a wider measure of freedom and justice for all members of the society. They believe that this is consonant with the values of the gospel and that the church should support the government at this crucial stage against its critics, both internal and external. The future of the nation, confronted by staggering economic and political problems, is in doubt, and it is too early to trace the shape Nicaraguan society will take. They are willing to run the risks presented by evangelical community involvement in this struggle.

World Scene

Colombian guerrillas killed Chester Bitterman III, the 28-year-old Wycliffe Bible translator they had held hostage for a month and a half. His body, with a bullet lodged in the heart, was located in Bogotá on March 7. A full report is scheduled for next issue.

Believers within the Catholic charismatic movement in Colombia are under intense pressure to break off their associations with evangelicals or leave the movement. At least in the department (state) of Cordoba, the local hierarchy is leading a drive directed against Manuel Meneses, pastor of the evangelical church in the capital city of Montería that belongs to the Association of Churches of the Caribbean (related to the Latin America Mission). Pastor Meneses was instrumental in introducing aspects of renewal to Roman Catholics in the region.

Ireland is not so monolithically Roman Catholic as feverish Ulster orators would have their audiences believe. (Militant Protestant Ian Paisley, in a political rally in Northern Ireland last month, called Ireland a “priest-ridden banana republic.”) A case in point: Baptists opened a new 120-seat church building in Letterkenny recently—the first building to be erected by Baptists in the Republic since 1904. Some 300 gathered to celebrate the event with pastor Clive Johnson and his 16-member congregation.

A third church building belonging to evangelicals has been burned down in the French city of Lyon. Correspondent Noreen Vajko (who reported the first two attacks in CT. March 13, p. 64) says these acts of violence have for the first time built a general awareness that evangelicals are not merely a cult. She quotes one newspaper that even declared. “It is very hard to understand what motivated those who burned down the churches of such dynamic believers.”

A remarkable growth of unofficial church activities in Czechoslovakia is leading to countermeasures by the authorities. Secret agents in the eastern (or Slovak) half of the country have been trained to track down clandestine gatherings such as Bible study groups or retreats for young people. The West German Catholic Information Agency, KNA, reports that 30 such agents operate in Bratislava University alone. Reports suggest that 200 secret police have been recruited from the western (or Czech) half of the country to help comb the mountainous Slovakian countryside for prayer meetings and discussion groups inspired by the “Oasis” youth renewal movement in Poland.

There were 307 Christian prisoners in the Soviet Union at the beginning of the year. The computation comes from Keston College, the research center in England that gathers and disseminates information on the condition of religious believers in Communist lands. The largest groupings were Baptists, with 94, Adventists, 53, Orthodox, 36, Pentecostals, 35.

Christians in Jos, Nigeria, gave a cash offering of nearly $100,000 at a service launching new seminary. The January offering was for an initial construction phase to accommodate 40 students for the seminary, sponsored by the Evangelical Churches of West Africa (churches of Sudan Interior Mission origin). “We must forget foreign aid!” admonished ECWA treasurer Bala Angbazo. “Not the government, not the missionaries—ECWA will finish this seminary in one year!” The ECWA Women’s Fellowship sang a song composed for the occasion, beating on clay pots and shaking bead-covered gourds.

South Africa’s Dutch Reformed Church (NGK) has officially rebuked nine of its prominent theologians for their indictments of the denomination’s defense of apartheid. Best known of the critics is F. E. O’Brien Geldenhuys, who resigned his position as director for ecumenical affairs at the end of last year because he found it virtually impossible to establish ties with other churches. In an interview with Rapport magazine, he charged that the NGK is “in a moral crisis and is internally paralyzed,” leading it to isolation. A regional synodal commission replied that Geldenhuys’s statement was “unbrotherly and irresponsible.” It reiterated its belief that racial separation is justified by Scripture, and that the primary task of the church is reconciliation between God and man, not man and man.

The Anglican Church will no longer be allowed to function in Iran. That was the announcement made by Iranian Prosecutor General Ali Qoddousi last month at the same time he announced the release of the three Anglican missionaries wrongly held for six months. This latest anti-Western move by Iran would appear to have limited effect, since most Anglican churches had already closed during the course of the revolution. Back in England, Jean Waddell revealed that her captors had choked her unconscious and then shot her in the arm. The three said they were treated well in confinement, and John Coleman said of himself and his wife Audrey, “Our feelings toward the Iranians have not changed one iota, and our great desire is to return eventually.”

Election last month of a Jordanian to be the Greek Orthodox patriarch of Jerusalem carried strong overtones for church jurisdiction and politics. The Greek Orthodox church is the largest Christian church among the Arab population of the region. Israeli officials favored Archbishop Vasilios of Caesaria for the post, made vacant last December by the death of Benedictos I. But election of the Jordanian Archbishop Deodoros was expected to stem pressures in Jordan to separate the Greek Orthodox community from the patriarchate in Israeli-controlled Jerusalem and to join the patriarchate in Damascus.

Transcendental Meditation’s claim that it is not a religion is a deliberate falsehood designed to give TM entrance into public institutions in the West. That is the conclusion of a study group of Christian students of neo-Hindu movements that met recently in India. The leader of TM, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, was in India, they reported, with some 3,000 of his followers to establish work there. In the programs conducted in Delhi, Hindu rites were followed and Indian staff was seen worshiping fire, the phallic symbol, and a photograph of the Yogi. A Western TM disciple was quoted by the Indian magazine Onlooker as saying, “The entire purpose of this enterprise [the inauguration of full-scale work by TM in India] is to push back the demon of Christianity.”

Christianity is flourishing in India. Some specifics, reported at the Evangelical Fellowship of India’s thirtieth annual conference in January at Mudurai, Tamil Nadu: The Friends Missionary Prayer Band has 163 Indian missionaries and forms new churches at the rate of one every 15 days. Churches in Northeast India have now sent out 352 missionaries (not including wives). The EFI Commission on Relief supplied drinking water to villages in South India by drilling 86 wells. As an indirect result of such efforts, 145 families were baptized in those villages.

Pope John Paul II hewed a moderate line in his visit to the Philippines, the Asian country with the most Roman Catholics. He let President Ferdinand Marcos know that even in exceptional situations, there is no justification for violating human rights. And he called on sugar plantation owners to provide just and fair wages instead of exploiting workers in order to compete and accumulate wealth. But he also reminded antigovernment priests and nuns that their main duty is to serve the gospel and not to engage in social work. In a country where many men keep “minor” or “second” wives, the Pope came down hard on polygamy. He also disclosed that the Vatican is exploring recognition of the independent Catholic church in China and establishing diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic.

Government aid to private schools in Australia has been vindicated by its high court. The 6-to-1 ruling last month rebuffed an eight-year effort by a coalition of groups that favor strict separation of church and state. It argued that such tax support violated the constitution by “establishing” religion. The chief justice replied that a law which may “indirectly enable a church to further the practice of religion is a long way from a law to establish religion.”