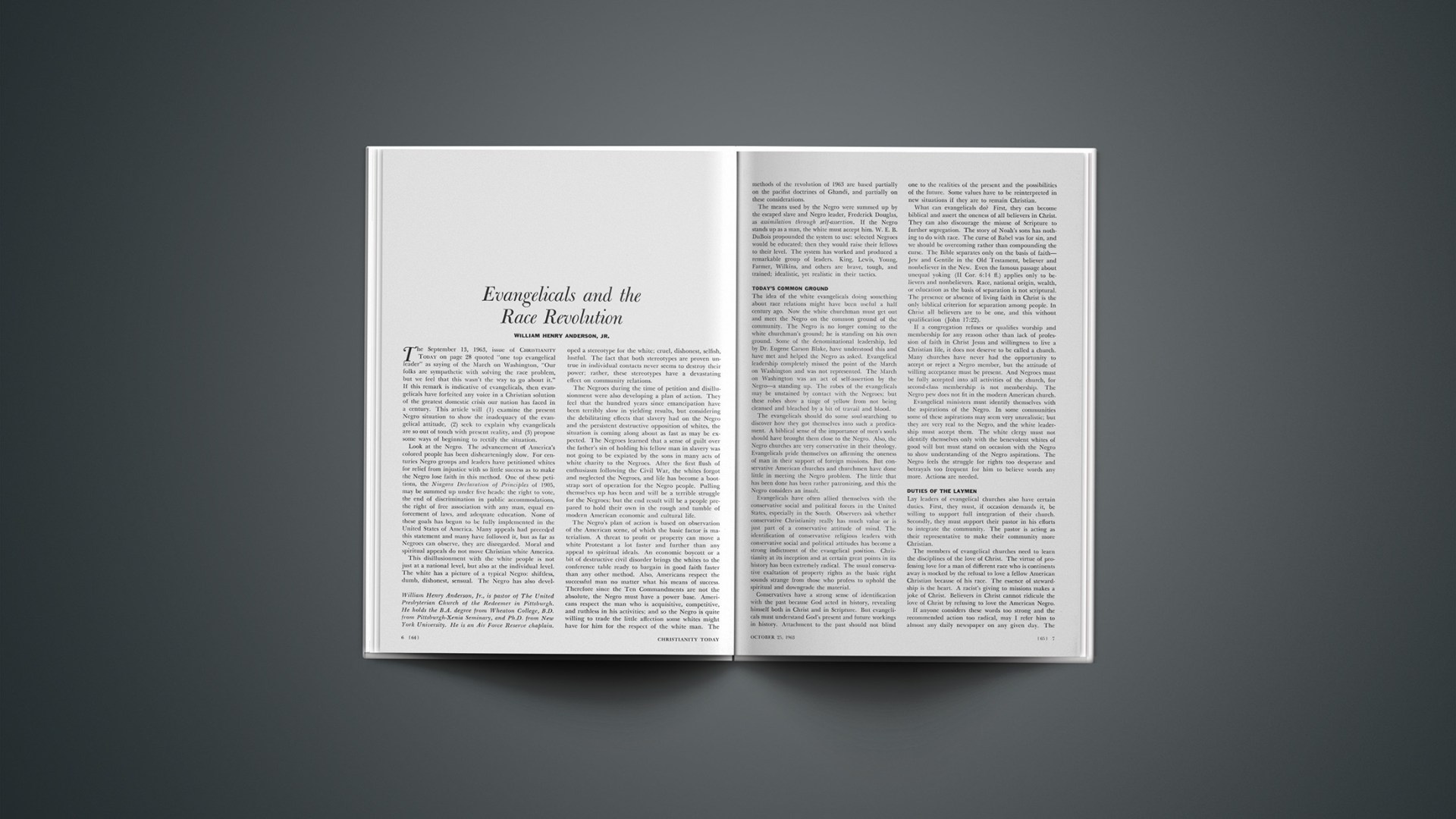

The September 13, 1963, issue of CHRISTIANITY TODAY on page 28 quoted “one top evangelical leader” as saying of the March on Washington, “Our folks are sympathetic with solving the race problem, but we feel that this wasn’t the Way to go about it.” If this remark is indicative of evangelicals, then evangelicals have forfeited any voice in a Christian solution of the greatest domestic crisis our nation has faced in a century. This article will (1) examine the present Negro situation to show the inadequacy of the evangelical attitude, (2) seek to explain why evangelicals are so out of touch with present reality, and (3) propose some ways of beginning to rectify the situation.

Look at the Negro. The advancement of America’s colored people has been dishearteningly slow. For centuries Negro groups and leaders have petitioned whites for relief from injustice with so little success as to make the Negro lose faith in this method. One of these petitions, the Niagara Declaration of Principles of 1905, may be summed up under five heads: the right to vote, the end of discrimination in public accommodations, the right of free association with any man, equal enforcement of laws, and adequate education. None of these goals has begun to be fully implemented in the United States of America. Many appeals had preceded this statement and many have followed it, but as far as Negroes can observe, they are disregarded. Moral and spiritual appeals do not move Christian white America.

This disillusionment with the white people is not just at a national level, but also at the individual level. The white has a picture of a typical Negro: shiftless, dumb, dishonest, sensual. The Negro has also developed a stereotype for the white; cruel, dishonest, selfish, lustful. The fact that both stereotypes are proven untrue in individual contacts never seems to destroy their power; rather, these stereotypes have a devastating effect on community relations.

The Negroes during the time of petition and disillusionment were also developing a plan of action. They feel that the hundred years since emancipation have been terribly slow in yielding results, but considering the debilitating effects that slavery had on the Negro and the persistent destructive opposition of whites, the situation is coming along about as fast as may be expected. The Negroes learned that a sense of guilt over the father’s sin of holding his fellow man in slavery was not going to be expiated by the sons in many acts of while charity to the Negroes. After the first flush of enthusiasm following the Civil War, the whites forgot and neglected the Negroes, and life has become a bootstrap sort of operation for the Negro people. Pulling themselves up has been and will be a terrible struggle for the Negroes; but the end result will be a people prepared to hold their own in the rough and tumble of modern American economic and cultural life.

The Negro’s plan of action is based on observation of the American scene, of which the basic factor is materialism. A threat to profit or property can move a white Protestant a lot faster and further than any appeal to spiritual ideals. An economic boycott or a bit of destructive civil disorder brings the whites to the conference table ready to bargain in good faith faster than any other method. Also, Americans respect the successful man no matter what his means of success. Therefore since the Ten Commandments are not the absolute, the Negro must have a power base. Americans respect the man who is acquisitive, competitive, and ruthless in his activities; and so the Negro is quite willing to trade the little affection some whites might have for him for the respect of the white man. The methods of the revolution of 1963 are based partially on the pacifist doctrines of Ghandi, and partially on these considerations.

The means used by the Negro were summed up by the escaped slave and Negro leader, Frederick Douglas, as assimilation through self-assertion. If the Negro stands up as a man, the white must accept him. W. E. B. DuBois propounded the system to use: selected Negroes would be educated; then they would raise their fellows to their level. The system has worked and produced a remarkable group of leaders. King, Lewis, Young, Farmer, Wilkins, and others are brave, tough, and trained; idealistic, yet realistic in their tactics.

Today’S Common Ground

The idea of the white evangelicals doing something about race relations might have been useful a half century ago. Now the white churchman must get out and meet the Negro on the common ground of the community. The Negro is no longer coming to the white churchman’s ground; he is standing on his own ground. Some of the denominational leadership, led by Dr. Eugene Carson Blake, have understood this and have met and helped the Negro as asked. Evangelical leadership completely missed the point of the March on Washington and was not represented. The March on Washington was an act of self-assertion by the Negro—a standing up. The robes of the evangelicals may be unstained by contact with the Negroes; but these robes show a tinge of yellow from not being cleansed and bleached by a bit of travail and blood.

The evangelicals should do some soul-searching to discover how they got themselves into such a predicament. A biblical sense of the importance of men’s souls should have brought them close to the Negro. Also, the Negro churches are very conservative in their theology. Evangelicals pride themselves on affirming the oneness of man in their support of foreign missions. But conservative American churches and churchmen have done little in meeting the Negro problem. The little that has been done has been rather patronizing, and this the Negro considers an insult.

Evangelicals have often allied themselves with the conservative social and political forces in the United States, especially in the South. Observers ask whether conservative Christianity really has much value or is just part of a conservative attitude of mind. The identification of conservative religious leaders with conservative social and political attitudes has become a strong indictment of the evangelical position. Christianity at its inception and at certain great points in its history has been extremely radical. The usual conservative exaltation of property rights as the basic right sounds strange from those who profess to uphold the spiritual and downgrade the material.

Conservatives have a strong sense of identification with the past because God acted in history, revealing himself both in Christ and in Scripture. But evangelicals must understand God’s present and future workings in history. Attachment to the past should not blind one to the realities of the present and the possibilities of the future. Some values have to be reinterpreted in new situations if they are to remain Christian.

What can evangelicals do? First, they can become biblical and assert the oneness of all believers in Christ. They can also discourage the misuse of Scripture to further segregation. The story of Noah’s sons has nothing to do with race. The curse of Babel was for sin, and we should be overcoming rather than compounding the curse. The Bible separates only on the basis of faith—Jew and Gentile in the Old Testament, believer and nonbeliever in the New. Even the famous passage about unequal yoking (2 Cor. 6:14 ff.) applies only to believers and nonbelievers. Race, national origin, wealth, or education as the basis of separation is not scriptural. The presence or absence of living faith in Christ is the only biblical criterion for separation among people. In Christ all believers are to be one, and this without qualification (John 17:22).

If a congregation refuses or qualifies worship and membership for any reason other than lack of profession of faith in Christ Jesus and willingness to live a Christian life, it does not deserve to be called a church. Many churches have never had the opportunity to accept or reject a Negro member, but the attitude of willing acceptance must be present. And Negroes must be fully accepted into all activities of the church, for second-class membership is not membership. The Negro pew does not fit in the modern American church.

Evangelical ministers must identify themselves with the aspirations of the Negro. In some communities some of these aspirations may seem very unrealistic; but they are very real to the Negro, and the white leadership must accept them. The white clergy must not identify themselves only with the benevolent whites of good will but must stand on occasion with the Negro to show understanding of the Negro aspirations. The Negro feels the struggle for rights too desperate and betrayals too frequent for him to believe words any more. Actions are needed.

Duties Of The Laymen

Lay leaders of evangelical churches also have certain duties. First, they must, if occasion demands it, be willing to support full integration of their church. Secondly, they must support their pastor in his efforts to integrate the community. The pastor is acting as their representative to make their community more Christian.

The members of evangelical churches need to learn the disciplines of the love of Christ. The virtue of professing love for a man of different race who is continents away is mocked by the refusal to love a fellow American Christian because of his race. The essence of stewardship is the heart. A racist’s giving to missions makes a joke of Christ. Believers in Christ cannot ridicule the love of Christ by refusing to love the American Negro.

If anyone considers these words too strong and the recommended action too radical, may I refer him to almost any daily newspaper on any given day. The Negro revolution is on its way and must be a revolution in the name of Christ. Read James Baldwin’s collection of essays under the title Nobody Knows My Name to understand present Negro attitudes. Read the New York Times’s résumé (August 29, 1963) of the speeches at the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington to learn the Negro’s goals. Read A Documentary History of the Negro People in the United States to learn why the Negro distrusts the benevolence and good will of the whites.

We may find it impossible to become unconscious of race. We may never be able to rid ourselves of the consciousness that the man to whom we are speaking is a Negro. But we can stop hurting our fellow in Christ. We have to love him as ourselves. We have to make sure his life is realized in its potential alongside ours. At best we communicate little with our fellow Christians and walk so lonesomely. But if we shut a fellow believer in Christ out of what we can give to one another in love, denying fullness of life as it might be ours to give, we deny our Christian profession.

The Church in the national crisis of the Revolution did quite well; in the national crisis of the Civil War it brought up the rear post facto; but in the present national crisis the Church has not distinguished itself. Some clergymen have distinguished themselves as heroes of faith, and some denominational agencies have testified of the love of Christ. The United Presbyterian Church has done better than others, though largely as a leadership project, not at the level of the rank and file.

Evangelicals have developed a habit of bland disregard of the social questions which have excited our nation. As it turned out in the past, they got away with it. But this integration question is a different matter. The twentieth century, as DuBois said at its beginning, is the century of race. Disregard of this problem could so discredit the evangelical cause as to bring it to disrepute and oblivion. The evangelicals have adopted a pooh-pooh, hands-off, none-of-our-business attitude. The Negro has gotten this far without any vigorous evangelical help, and so he probably will not need it in the future. Therefore the evangelicals are hurting only themselves. The conservative Protestant church had better get involved in this Negro revolution or face inevitable judgment by the Negroes and youth of today and the historians of tomorrow.

William Henry Anderson, Jr., is pastor of The United Presbyterian Church of the Redeemer in Pittsburgh. He holds the B.A. degree from Wheaton College, B.D. from Pittsburgh-Xenia Seminary, and Ph.D. from New York University. He is an Air Force Reserve chaplain.