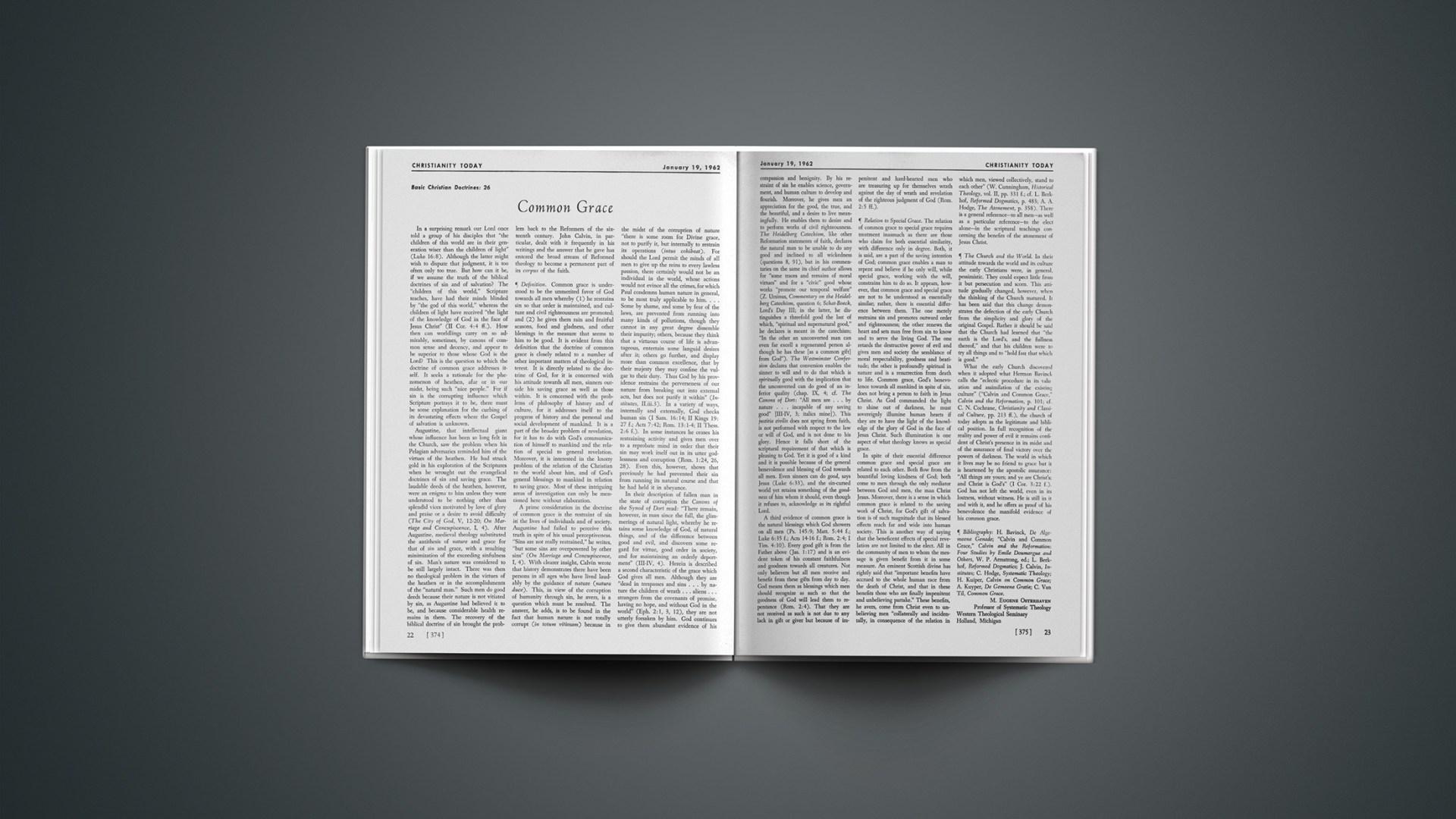

In a surprising remark our Lord once told a group of his disciples that “the children of this world are in their generation wiser than the children of light” (Luke 16:8). Although the latter might wish to dispute that judgment, it is too often only too true. But how can it be, if we assume the truth of the biblical doctrines of sin and of salvation? The “children of this world,” Scripture teaches, have had their minds blinded by “the god of this world,” whereas the children of light have received “the light of the knowledge of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (2 Cor. 4:4 ff.). How then can worldlings carry on so admirably, sometimes, by canons of common sense and decency, and appear to be superior to those whose God is the Lord? This is the question to which the doctrine of common grace addresses itself. It seeks a rationale for the phenomenon of heathen, afar or in our midst, being such “nice people.” For if sin is the corrupting influence which Scripture portrays it to be, there must be some explanation for the curbing of its devastating effects where the Gospel of salvation is unknown.

Augustine, that intellectual giant whose influence has been so long felt in the Church, saw the problem when his Pelagian adversaries reminded him of the virtues of the heathen. He had struck gold in his exploration of the Scriptures when he wrought out the evangelical doctrines of sin and saving grace. The laudable deeds of the heathen, however, were an enigma to him unless they were understood to be nothing other than splendid vices motivated by love of glory and praise or a desire to avoid difficulty (The City of God, V, 12–20; On Marriage and Concupiscence, I, 4). After Augustine, medieval theology substituted the antithesis of nature and grace for that of sin and grace, with a resulting minimization of the exceeding sinfulness of sin. Man’s nature was considered to be still largely intact. There was then no theological problem in the virtues of the heathen or in the accomplishments of the “natural man.” Such men do good deeds because their nature is not vitiated by sin, as Augustine had believed it to be, and because considerable health remains in them. The recovery of the biblical doctrine of sin brought the problem back to the Reformers of the sixteenth century. John Calvin, in particular, dealt with it frequently in his writings and the answer that he gave has entered the broad stream of Reformed theology to become a permanent part of its corpus of the faith.

Definition. Common grace is understood to be the unmerited favor of God towards all men whereby (1) he restrains sin so that order is maintained, and culture and civil righteousness are promoted; and (2) he gives them rain and fruitful seasons, food and gladness, and other blessings in the measure that seems to him to be good. It is evident from this definition that the doctrine of common grace is closely related to a number of other important matters of theological interest. It is directly related to the doctrine of God, for it is concerned with his attitude towards all men, sinners outside his saving grace as well as those within. It is concerned with the problems of philosophy of history and of culture, for it addresses itself to the progress of history and the personal and social development of mankind. It is a part of the broader problem of revelation, for it has to do with God’s communication of himself to mankind and the relation of special to general revelation. Moreover, it is interested in the knotty problem of the relation of the Christian to the world about him, and of God’s general blessings to mankind in relation to saving grace. Most of these intriguing areas of investigation can only be mentioned here without elaboration.

A prime consideration in the doctrine of common grace is the restraint of sin in the lives of individuals and of society. Augustine had failed to perceive this truth in spite of his usual perceptiveness. “Sins are not really restrained,” he writes, “but some sins are overpowered by other sins” (On Marriage and Concupiscence, I, 4). With clearer insight, Calvin wrote that history demonstrates there have been persons in all ages who have lived laudably by the guidance of nature (natura duce). This, in view of the corruption of humanity through sin, he avers, is a question which must be resolved. The answer, he adds, is to be found in the fact that human nature is not totally corrupt (in totum vitiosam) because in the midst of the corruption of nature “there is some room for Divine grace, not to purify it, but internally to restrain its operations (intus cohibeat). For should the Lord permit the minds of all men to give up the reins to every lawless passion, there certainly would not be an individual in the world, whose actions would not evince all the crimes, for which Paul condemns human nature in general, to be most truly applicable to him.… Some by shame, and some by fear of the laws, are prevented from running into many kinds of pollutions, though they cannot in any great degree dissemble their impurity; others, because they think that a virtuous course of life is advantageous, entertain some languid desires after it; others go further, and display more than common excellence, that by their majesty they may confine the vulgar to their duty. Thus God by his providence restrains the perverseness of our nature from breaking out into external acts, but does not purify it within” (Institutes, II.iii.3). In a variety of ways, internally and externally, God checks human sin (1 Sam. 16:14; 2 Kings 19:27 f.; Acts 7:42; Rom. 13:1–4; 2 Thess. 2:6 f.). In some instances he ceases his restraining activity and gives men over to a reprobate mind in order that their sin may work itself out in its utter godlessness and corruption (Rom. 1:24, 26, 28). Even this, however, shows that previously he had prevented their sin from running its natural course and that he had held it in abeyance.

In their description of fallen man in the state of corruption the Canons of the Synod of Dort read: “There remain, however, in man since the fall, the glimmerings of natural light, whereby he retains some knowledge of God, of natural things, and of the difference between good and evil, and discovers some regard for virtue, good order in society, and for maintaining an orderly deportment” (III–IV, 4). Herein is described a second characteristic of the grace which God gives all men. Although they are “dead in trespasses and sins … by nature the children of wrath … aliens … strangers from the covenants of promise, having no hope, and without God in the world” (Eph. 2:1, 3, 12), they are not utterly forsaken by him. God continues to give them abundant evidence of his compassion and benignity. By his restraint of sin he enables science, government, and human culture to develop and flourish. Moreover, he gives men an appreciation for the good, the true, and the beautiful, and a desire to live meaningfully. He enables them to desire and to perform works of civil righteousness. The Heidelberg Catechism, like other Reformation statements of faith, declares the natural man to be unable to do any good and inclined to all wickedness (questions 8, 91), but in his commentaries on the same its chief author allows for “some traces and remains of moral virtues” and for a “civic” good whose works “promote our temporal welfare” (Z. Ursinus, Commentary on the Heidelberg Catechism, question 6; Schat-Boeck, Lord’s Day III; in the latter, he distinguishes a threefold good the last of which, “spiritual and supernatural good,” he declares is meant in the catechism; “In the other an unconverted man can even far excell a regenerated person although he has these [as a common gift] from God”). The Westminster Confession declares that conversion enables the sinner to will and to do that which is spiritually good with the implication that the unconverted can do good of an inferior quality (chap. IX, 4; cf. The Canons of Dort: “All men are … by nature … incapable of any saving good” [III–IV, 3; italics mine]). This justitia civilis does not spring from faith, is not performed with respect to the law or will of God, and is not done to his glory. Hence it falls short of the scriptural requirement of that which is pleasing to God. Yet it is good of a kind and it is possible because of the general benevolence and blessing of God towards all men. Even sinners can do good, says Jesus (Luke 6:33), and the sin-cursed world yet retains something of the goodness of him whom it should, even though it refuses to, acknowledge as its rightful Lord.

A third evidence of common grace is the natural blessings which God showers on all men (Ps. 145:9; Matt. 5:44 f.; Luke 6:35 f.; Acts 14–16 f.; Rom. 2:4; 1 Tim. 4:10). Every good gift is from the Father above (Jas. 1:17) and is an evident token of his constant faithfulness and goodness towards all creatures. Not only believers but all men receive and benefit from these gifts from day to day. God means them as blessings which men should recognize as such so that the goodness of God will lead them to repentance (Rom. 2:4). That they are not received as such is not due to any lack in gift or giver but because of impenitent and hard-hearted men who are treasuring up for themselves wrath against the day of wrath and revelation of the righteous judgment of God (Rom. 2:5 ff.).

Relation to Special Grace. The relation of common grace to special grace requires treatment inasmuch as there are those who claim for both essential similarity, with difference only in degree. Both, it is said, are a part of the saving intention of God; common grace enables a man to repent and believe if he only will, while special grace, working with the will, constrains him to do so. It appears, however, that common grace and special grace are not to be understood as essentially similar; rather, there is essential difference between them. The one merely restrains sin and promotes outward order and righteousness; the other renews the heart and sets man free from sin to know and to serve the living God. The one retards the destructive power of evil and gives men and society the semblance of moral respectability, goodness and beatitude; the other is profoundly spiritual in nature and is a resurrection from death to life. Common grace, God’s benevolence towards all mankind in spite of sin, does not bring a person to faith in Jesus Christ. As God commanded the light to shine out of darkness, he must sovereignly illumine human hearts if they are to have the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ. Such illumination is one aspect of what theology knows as special grace.

In spite of their essential difference common grace and special grace are related to each other. Both flow from the bountiful loving kindness of God; both come to men through the only mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus. Moreover, there is a sense in which common grace is related to the saving work of Christ, for God’s gift of salvation is of such magnitude that its blessed effects reach far and wide into human society. This is another way of saying that the beneficent effects of special revelation are not limited to the elect. All in the community of men to whom the message is given benefit from it in some measure. An eminent Scottish divine has rightly said that “important benefits have accrued to the whole human race from the death of Christ, and that in these benefits those who are finally impenitent and unbelieving partake.” These benefits, he avers, come from Christ even to unbelieving men “collaterally and incidentally, in consequence of the relation in which men, viewed collectively, stand to each other” (W. Cunningham, Historical Theology, vol. II, pp. 331 f.; cf. L. Berkhof, Reformed Dogmatics, p. 483; A. A. Hodge, The Atonement, p. 358). There is a general reference—to all men—as well as a particular reference—to the elect alone—in the scriptural teachings concerning the benefits of the atonement of Jesus Christ.

The Church and the World. In their attitude towards the world and its culture the early Christians were, in general, pessimistic. They could expect little from it but persecution and scorn. This attitude gradually changed, however, when the thinking of the Church matured. It has been said that this change demonstrates the defection of the early Church from the simplicity and glory of the original Gospel. Rather it should be said that the Church had learned that “the earth is the Lord’s, and the fullness thereof,” and that his children were to try all things and to “hold fast that which is good.”

What the early Church discovered when it adopted what Herman Bavinck calls the “eclectic procedure in its valuation and assimilation of the existing culture” (“Calvin and Common Grace,” Calvin and the Reformation, p. 101; cf. C. N. Cochrane, Christianity and Classical Culture, pp. 213 ff.), the church of today adopts as the legitimate and biblical position. In full recognition of the reality and power of evil it remains confident of Christ’s presence in its midst and of the assurance of final victory over the powers of darkness. The world in which it lives may be no friend to grace but it is heartened by the apostolic assurance: “All things are yours; and ye are Christ’s: and Christ is God’s” (1 Cor. 3:22 f.). God has not left the world, even in its lostness, without witness. He is still in it and with it, and he offers as proof of his benevolence the manifold evidence of his common grace.

Bibliography: H. Bavinck, De Algemeene Genade; “Calvin and Common Grace,” Calvin and the Reformation: Four Studies by Emile Doumergue and Others, W. P. Armstrong, ed.; L. Berkhof, Reformed Dogmatics; J. Calvin, Institutes; C. Hodge, Systematic Theology; H. Kuiper, Calvin on Common Grace; A. Kuyper, De Gemeene Gratie; C. Van Til, Common Grace.

Professor of Systematic Theology

Western Theological Seminary

Holland, Michigan