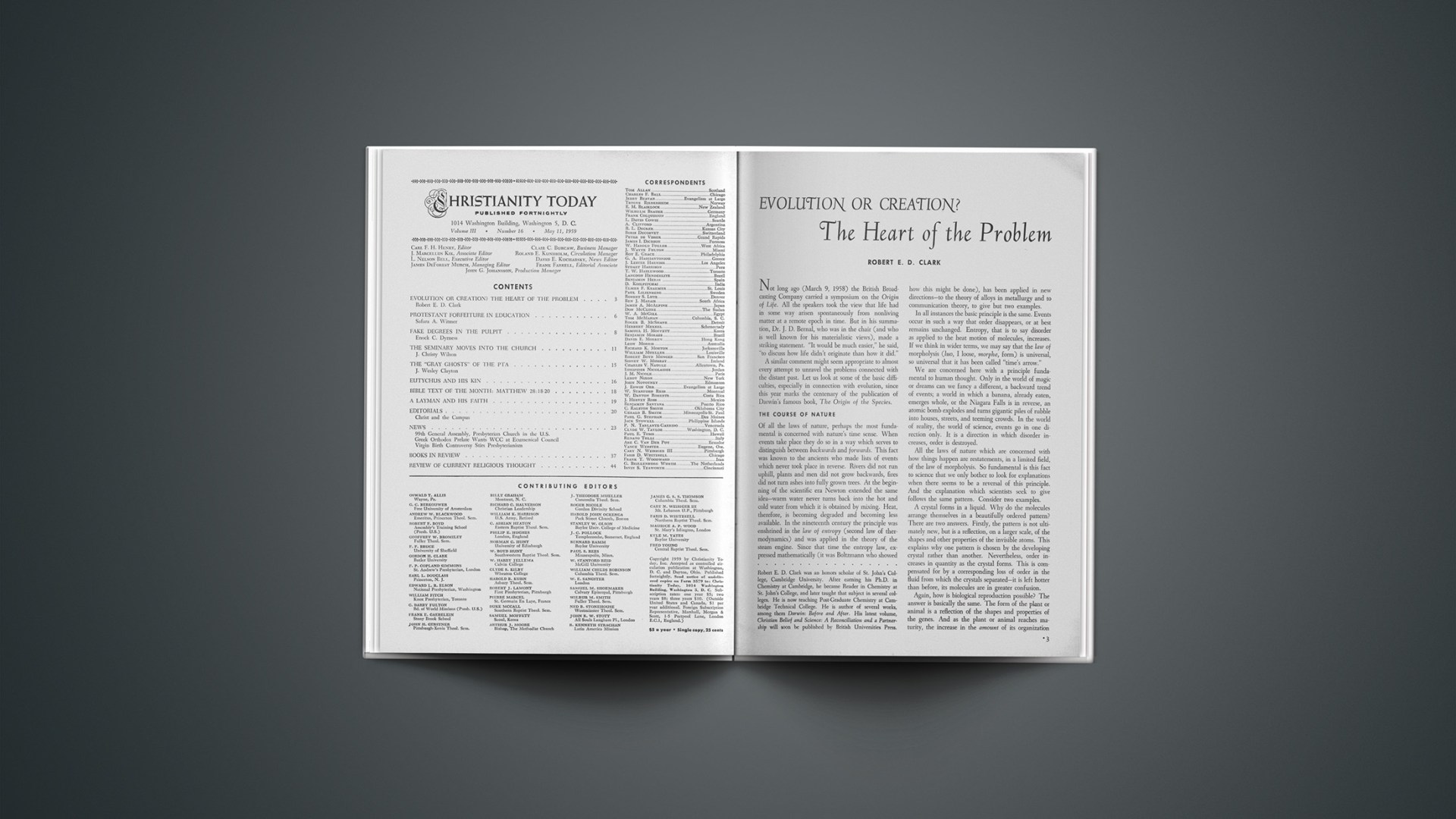

Not long ago (March 9, 1958) the British Broadcasting Company carried a symposium on the Origin of Life. All the speakers took the view that life had in some way arisen spontaneously from nonliving matter at a remote epoch in time. But in his summation, Dr. J. D. Bernal, who was in the chair (and who is well known for his materialistic views), made a striking statement. “It would be much easier,” he said, “to discuss how life didn’t originate than how it did.”

A similar comment might seem appropriate to almost every attempt to unravel the problems connected with the distant past. Let us look at some of the basic difficulties, especially in connection with evolution, since this year marks the centenary of the publication of Darwin’s famous book, The Origin of the Species.

The Course Of Nature

Of all the laws of nature, perhaps the most fundamental is concerned with nature’s time sense. When events take place they do so in a way which serves to distinguish between backwards and forwards. This fact was known to the ancients who made lists of events which never took place in reverse. Rivers did not run uphill, plants and men did not grow backwards, fires did not turn ashes into fully grown trees. At the beginning of the scientific era Newton extended the same idea—warm water never turns back into the hot and cold water from which it is obtained by mixing. Heat, therefore, is becoming degraded and becoming less available. In the nineteenth century the principle was enshrined in the law of entropy (second law of thermodynamics) and was applied in the theory of the steam engine. Since that time the entropy law, expressed mathematically (it was Boltzmann who showed how this might be done), has been applied in new directions—to the theory of alloys in metallurgy and to communication theory, to give but two examples.

In all instances the basic principle is the same. Events occur in such a way that order disappears, or at best remains unchanged. Entropy, that is to say disorder as applied to the heat motion of molecules, increases. If we think in wider terms, we may say that the law of morpholysis (luo, I loose, morphe, form) is universal, so universal that it has been called “time’s arrow.”

We are concerned here with a principle fundamental to human thought. Only in the world of magic or dreams can we fancy a different, a backward trend of events; a world in which a banana, already eaten, emerges whole, or the Niagara Falls is in reverse, an atomic bomb explodes and turns gigantic piles of rubble into houses, streets, and teeming crowds. In the world of reality, the world of science, events go in one direction only. It is a direction in which disorder increases, order is destroyed.

All the laws of nature which are concerned with how things happen are restatements, in a limited field, of the law of morpholysis. So fundamental is this fact to science that we only bother to look for explanations when there seems to be a reversal of this principle. And the explanation which scientists seek to give follows the same pattern. Consider two examples.

A crystal forms in a liquid. Why do the molecules arrange themselves in a beautifully ordered pattern? There are two answers. Firstly, the pattern is not ultimately new, but is a reflection, on a larger scale, of the shapes and other properties of the invisible atoms. This explains why one pattern is chosen by the developing crystal rather than another. Nevertheless, order increases in quantity as the crystal forms. This is compensated for by a corresponding loss of order in the fluid from which the crystals separated—it is left hotter than before, its molecules are in greater confusion.

Again, how is biological reproduction possible? The answer is basically the same. The form of the plant or animal is a reflection of the shapes and properties of the genes. And as the plant or animal reaches maturity, the increase in the amount of its organization (but not the type of organization—why this corresponds, say, to a sheep rather than a buttercup) is compensated for by loss in the order of its surroundings: energy stored in food or sunlight is degraded.

The answers we have given in these two examples are typical of the answers which science must give to every problem that is posed. Only when an answer can be given along these lines is it even possible to begin to tackle the thousand and one questions of detail which must arise if a full understanding is to be reached. If we cannot start to answer a question at this level, then we may just as well invoke magic. We are demanding that an explanation should be sought in terms which are inconsistent with scientific thought.

The Question Of Origins

Now the startling point emerges that whenever we look into the question of origins we find that, at some stages at least, events must have taken place to which answers of the kind considered cannot be given.

The energy of the universe was “wound up” at the beginning; in all subsequent events it has become less and less available. The chemical elements came into existence endowed from the start with astonishingly “ordered” potentialities. Was it chance that gave hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and the rest their remarkable properties, many of which are so fundamental to life? Our planet also came to be placed at the right distance from the sun, with oceans to keep its temperature even, with tilted axis to give the seasons, with its weight correct to allow of the escape of hydrogen but the retention of oxygen, and so on.

And somehow or other life came: three dimensional structures of atoms, arranged in shapes of bewildering complexity, blueprinted with instructions for self-reproduction! With the passing of time new and yet more intricate structures came into being: elaborate mechanisms for flight; equipment for detecting position relative to surroundings by picking up reflected electromagnetic rays; fantastic gadgets for effecting orientation in gravitational fields; pumps, complete with valves and elaborate timing mechanisms, for pumping fluids; mechanisms for detecting and relaying information about touch, heat, cold and injury; mechanisms for picking up and interpreting rhythmic atmospheric disturbances at fastastically low energy levels and yet capable of responding without injury to levels a thousand billion times as great; objects like gigantic telephone exchanges connected with subscribers by the billion … and so we might continue, indefinitely, for new mechanisms are continually coming to light.

That all this happened there is no doubt. We ourselves are part of the story. But how did it happen? Can we even begin to answer the question along the lines that we employ when we commence to tackle every other problem that science poses? It seems not. We can understand how a new type of order, once established, can multiply by degrading chemical compounds and quanta of light, but how do thousands of new kinds of order arise?

How Did It All Begin?

A century ago Darwin suggested that chance variations, followed by the survival of the fittest, would, in the end, give rise to the appearance of design. Perhaps he was right—within the limits of the very simple. Yet few suppose that Darwin’s theory goes to the heart of the problem.

Survival of the fittest could not explain the ordered nature of the energy of the universe, nor the properties of the chemical elements, nor the origin of the first forms of life which must have possessed great complexity in order to be alive at all. And although the idea had been a commonplace for a century, it has as yet done nothing to solve major biological difficulties, though it has done a good deal to solve minor ones.

Biological structures, like all functional structures, must be all there at once or they serve no purpose. A car without its wheels or a tape recorder without its tape will, in terms of natural selection, be rejected as useless. Yet highly specialized organs are found in nature and it is hard, indeed, to suppose that they could all have arisen gradually. In some cases suggestions have been made as to the uses which uncompleted structures might have had. But common sense revolts against the suggestion that all cases can be explained along these lines. As well might one expect an enormous sale of wheelless automobiles on the ground that, by an off-chance, they would prove useful as rabbit hutches.

Even more basic is the difficulty afforded by size. It is a principle in engineering that one cannot, simply, imitate a small machine on a much larger scale. There comes a time when mere modification will not do; a basic redesign is called for. This fact arises from the consideration that weight increases as the cube of dimensions, but surface area and forces, which can be transmitted by wires, tendons, or muscles, vary only as the square. For this reason a fly the size of a dog would break its legs and a dog the size of a fly would be unable to maintain its body heat. So if evolution started with very small organisms there would come a time when, as a result of size increase, small naturally-selected modifications would no longer prove useful. Radically new designs would be necessary for survival. But by its very nature, natural selection could not provide for such redesign.

From all this and much more besides, it becomes increasingly clear that it would be easier to show by science that evolution is impossible than to explain how it happened. The difficulties are, in fact, so great that we may well wonder why they are not more often recognized. But perhaps they are. In the nineteenth century scientists hoped to discover truth about nature. Today, many say that not truth but the creation of theories which will stimulate discovery and thought is the aim of science. Darwin’s theory of evolution is certainly of this kind. So the biologist will sometimes say, quite blandly, that for him it is a choice between something he does not really believe in or nothing at all. “No amount of argument or clever epigram, can disguise the inherent improbability of orthodoxy (orthodox evolutionary theory),” writes Professor Gray of Cambridge (England), “but most biologists think that it is better to think in terms of improbable events than not to think at all” (Nature, 1954, pp. 173, 227).

Science And Magic

Facing the evidence fairly, it is clear that no matter where we look we find confirmation of the biblical doctrine that “the things which are seen were not made of things which do appear.” But if we say that God created the world, or life, or did this or that, are we not resorting to explanations of the magical kind? Are we not turning our backs on science?

There are two answers to this. First, it is easy to postulate magic without realizing the fact. This is, in effect, just what theories of evolution do. While paying lip service to science, they postulate something opposed to the basic principle of all scientific thought—they postulate the creation, spontaneously, magically, in complete absence of observers, of radically new types of organization: the actual reversal of the law of morpholysis! If, then, when we say that God created the world, we are resorting to magic as an explanation, we do no worse than the materialistic evolutionist. Indeed, our attitude is to be preferred to his, for we do not disguise magic behind high-sounding words which are intended to sound scientific.

But, secondly, we must not forget that there is within the experience of each of us a nonmagical principle which is able to reverse the law of morpholysis. By thinking, by putting forth creative effort, we can create the very order that may so easily and so spontaneously be destroyed. Now this principle of creativity in the mind of man is not magic. Magic works without effort. You mutter abacadabra and the thing is done. But the man who spends years writing a book or designing a bridge knows that “power is gone out of him.” He creates by faith and by effort, not by magic.

When we think of the ultimate origins of nature we see many evidences of plan—or what looks like plan. It is as if the major (though not all the minor) instances of organization are the product of a Mind, of a kind not unlike our own, though unimaginably greater and more competent. It seems natural and sensible to take the evidence at its face value; to believe that God created the heaven and the earth. But there is no need to think of God as an almighty magician. The Bible speaks often of the forethought and care which God put into the creation (we even read that he rested from his labors), and in science we see vindication of its teaching. We ourselves, made in the image of God, are not magicians, and there is no need to think of God as a magician either.

END

We Quote:

WILLIAM FITCH

Minister of Knox Presbyterian Church, Toronto

The great halcyon days of the Christian Church have been days of Spirit-energized praying. Pentecost was granted to a church at prayer. New continents opened before the apostolic church as the church prayed. Revival times have always been marked by the ministry of men who “prayed without ceasing.” But tragically we live in a day when the program of the church is exalted and the prayer meeting forgotten. Everywhere mer look for new methods, new techniques, new presentations. Organization is on the throne. But the inspiration is lacking and the spirit of conviction does not fall upon men. Designs, projects, plans, promotions crowd our calendars; but we have forgotten that it is in quietness and in confidence we find strength. Our preaching is powerless because it is prayerless. Our lives are not saintly because they are not saturated with supplication. Our churches are not living fellowships, vibrant with the joy and assurance of eternity; and a great part of the reason is that we have lost the holy art of “being still and knowing that God is God.” And the result? Our generation passes by and they hear not the word of the Saviour. Here is the agony and the dilemma of the church today.—In a sermon during the recent jubilee of Knox Presbyterian Church, Toronto.

WILLIAM S. LASOR

Professor, Fuller Theological Seminary

What really makes me grit my teeth is the use of “Reverend” as a title. If you will take the trouble to look in your dictionary, you will discover that “Reverend” is not a title (like “Doctor”), but an adjective (like “Honorable”). The use of “Reverend” before the last name (“Reverend Ladd”) is as rude as using the last name alone. You might as well say, “Skinny Jones” or “Sloppy Johnson” as “Reverend Rasmussen.” Several correct ways of using “Reverend” are possible: “the Reverend George Smith,” “the Reverend Doctor Booth,” “the Reverend Professor Harrison.” It is just as correct to omit the word, and present the speaker as “Mister Jones,” or “Professor Longbeard.” A good method is to give the full title when first introducing the speaker (“Our guest speaker this morning is the Reverend Professor I. M. Longwinded, Ph.D.”), tell where he is from, and then present him by the simplest form (“Professor [or, Doctor] Longwinded”). Above all, be sincere—whether you mean it or not!—In Theology News and Notes, October, 1958.

Robert E. D. Clark was an honors scholar of St. John’s College, Cambridge University. After earning his Ph.D. in Chemistry at Cambridge, he became Reader in Chemistry at St. John’s College, and later taught that subject in several colleges. He is now teaching Post-Graduate Chemistry at Cambridge Technical College. He is author of several works, among them Darwin: Before and After. His latest volume, Christian Belief and Science: A Reconciliation and a Partnership will soon be published by British Universities Press.