The basic fact of biblical religion is that God pardons and accepts believing sinners (cf. Ps. 32:1–5; 130; Luke 7:47 ff.; 18:9–14; Acts 10:43; 1 John 1:7–2:2). Paul’s doctrine of justification by faith is an analytical exposition of this fact in its full theological connections. As stated by Paul (most fully in Romans and Galatians, though also in 2 Cor. 5:14 ff.; Eph. 2:1 ff.; Phil. 3:4 ff.), the doctrine of justification determines the whole character of Christianity as a religion of grace and faith. It defines the saving significance of Christ’s life and death by relating both to God’s law (Rom. 3:24 ff.; 5:16 ff.). It displays God’s justice in condemning and punishing sin, his mercy in pardoning and accepting sinners, and his wisdom in exercising both attributes harmoniously together through Christ (Rom. 3:23 ff.). It makes clear what at heart faith is—belief in Christ’s atoning death and justifying resurrection (Rom. 4:23 ff.; 10:8 ff.), and trust in him alone for righteousness (Phil. 3:8 f.). It makes clear what at heart Christian morality is—law keeping out of gratitude to the Saviour whose gift of righteousness made law keeping needless for acceptance (Rom. 7:1–6; 12:1 f.). It explains all hints, prophecies, and instances of salvation in the Old Testament (Rom. 1:17; 3:21; 4:1 ff.). It overthrows Jewish exclusivism (Gal. 2:15 ff.), and provides the basis on which Christianity becomes a religion for the world (Rom. 1:16; 3:29 f.). It is the heart of the Gospel. Luther justly termed it articulus stantis vel cadentis ecclesiae: a church that lapses from it can scarcely be called Christian.

The Meaning Of Justification

The biblical meaning of “justify” is to pronounce, accept, and treat as just, as, on the one hand, not penally liable, and, on the other, entitled to all the privileges due to those who have kept the Law. It is thus a forensic term, denoting a judicial act of administering the Law—in this case, by declaring a verdict of acquittal, and so excluding all possibility of condemnation. Justification thus settles the legal status of the person justified. (See Deut. 25:1; Prov. 17:15; Rom. 8:33 f. In Isa. 43:9, 26, “be justified” means “get the verdict.”) The justifying action of the Creator, who is the royal Judge of his world, has both a sentential and an executive, or declarative, aspect: God justifies first by reaching his verdict, and then by such sovereign action which makes his verdict known, and secures to the person justified the rights which are now his due. What is envisaged in Isaiah 45:25 and 50:8, for instance, is specifically a series of events which will publicly vindicate those whom God holds to be in the right.

The word is also used in a transferred sense for ascriptions of righteousness in nonforensic contexts. Thus, men are said to justify God when they confess him just (Luke 7:29; Rom. 3:4; Ps. 51:4), and themselves when they claim to be just (Job 32:2; Luke 10:29; 16:15). The passive can be used generally of being vindicated by events against suspicion, criticism, and mistrust (Matt. 11:19; Luke 7:35; 1 Tim. 3:16). In James 2:21, 24, 25, its reference is to the proof of a man’s acceptance with God which is given when his actions show that he has the kind of living, working faith to which God imputes righteousness.

James’ statement that Christians, like Abraham, are justified by works (vs. 24) is thus not contrary to Paul’s insistence that Christians, like Abraham, are justified by faith (Rom. 3:28; 4:1–5); rather it is complementary to it. James himself quotes Genesis 15:6 for exactly the same purpose Paul does—to show that it was faith which secured Abraham’s acceptance as righteous (vs. 23; cf. Rom. 4:3 ff.; Gal. 3:6 ff.). The justification which concerns James is not the believer’s original acceptance by God, but the subsequent vindication of his profession of faith by his life. It is in terminology, not thought, that James differs from Paul.

There is no lexical ground for the view of Chrysostom, Augustine, the medievals, and Roman theologians that “justify” means, or connotes as part of its meaning, “make righteous” (sc. by subjective spiritual renewal). The Tridentine definition of justification as “not only the remission of sins, but also the sanctification and renewal of the inward man” (Sess. VI, chap. vii) is erroneous.

Paul’S Doctrine Of Justification

The background of Paul’s doctrine was the Jewish conviction, universal in his time, that a day of judgment was coming in which God would condemn and punish all who had broken his laws. That day would terminate the present world order and usher in a golden age for those whom God judged worthy. This conviction, derived from prophetic expectations of “the day of the Lord” (Amos 5:19 ff.; Isa. 2:10–22; 13:6–11; Jer. 46:10; Obad. 15; Zeph. 1:14–2:3) and developed during the inter-testamental period under the influence of apocalyptic, had been emphatically confirmed by Christ (Matt. 11:22 ff.; 12:36 f.). Paul affirmed that Christ himself was the appointed representative through whom God would “judge the world in righteousness” in “the day of wrath and revelation of the righteous judgment of God” (Acts 17:31; Rom. 2:16). This, indeed, had been Christ’s own claim (John 5:27 ft.).

Paul sets out his doctrine of the judgment day in Romans 2:5–16. The principle of judgment will be exact retribution (“to every man according to his works,” vs. 6). The standard will be God’s Law. The evidence will be “the secrets of men” (vs. 16); the Judge is a searcher of hearts. Being himself just, he cannot be expected to justify any but the righteous, those who have kept his Law (Rom. 2:12, 13; cf. Exod. 23:7; 1 Kings 8:32). But the class of righteous men has no members. None is righteous; all have sinned (Rom. 3:9 ff.). The prospect, therefore, is one of universal condemnation, for Jew as well as Gentile; for the Jew who breaks the law is no more acceptable to God than anyone else (Rom. 2:17–27). All men, it seems, are under God’s wrath (Rom. 1:18) and doomed.

Against this black background, comprehensively expounded in Romans 1:18–3:20, Paul proclaims the present justification of sinners by grace through faith in Jesus Christ, apart from all works and despite all demerit (Rom. 3:21 ff.). This justification, though individually located at the time at which a man believes (Rom. 4:2; 5:1), is an eschatological once-for-all divine act, the final judgment brought into the present. The justifying sentence, once passed, is irrevocable. “The wrath” will not touch the justified (Rom. 5:9). Those accepted now are secure forever. Inquisition before Christ’s judgment seat (Rom. 14:10–12; 2 Cor. 5:10) may deprive them of certain rewards (1 Cor. 3:15), but never of their justified status. Christ will not call in question God’s justifying verdict; he will only declare, endorse, and implement it.

Justification has two sides. On the one hand, it means the pardon, remission and nonimputation of all sins, reconciliation to God, and the end of his enmity and wrath (Acts 13:39; Rom. 4:6 f.; 2 Cor. 5:19; Rom. 5:9 ff.). On the other hand, it means the bestowal of a righteous man’s status and a title to all the blessings promised to the just, a thought which Paul amplifies by linking justification with the adoption of believers as God’s sons and heirs (Rom. 8:14 ff; Gal. 4:4 ff.). Part of their inheritance they receive at once. Through the gift of the Holy Spirit, whereby God “seals” them as his when they believe (Eph. 1:13), they taste that quality of fellowship with God which belongs to the age to come and is called “eternal life.” Here is another eschatological reality brought into the present. Having in a real sense passed through the last judgment, the justified enter heaven on earth. Here and now, therefore, justification brings “life” (Rom. 5:18), though this is merely a foretaste of the fullness of life and glory which constitutes the “hope of righteousness” (Gal. 5:5) promised to the just (Rom. 2:7, 10), to which God’s justified children may look forward (Rom. 8:18 ff.). Both aspects of justification appear in Romans 5:1–2 where Paul says that justification brings, on the one hand, peace with God (because sin is pardoned) and, on the other, hope of the glory of God (because the believer is accepted as righteous). Justification thus means permanent reinstatement of favor and privilege as well as forgiveness of all sins.

The Ground Of Justification

Paul’s deliberately paradoxical reference to God as “justifying the ungodly” (Rom. 4:5)—the same Greek phrase as is used by the LXX in Exodus 23:7; Isaiah 5:23, of the corrupt judgment that God will not tolerate—reflects his awareness that this is a startling doctrine. Indeed, it seems flatly at variance with the Old Testament presentation of God’s essential righteousness as revealed in his actions as Legislator and Judge—a presentation which Paul himself assumes in Romans 1:18–3:20. The Old Testament insists that God is “righteous in all his ways” (Ps. 145:17), “a God … without iniquity” (Deut. 32:4; cf. Zeph. 3:5). The law of right and wrong, in conformity to which righteousness consists, has its being and fulfillment in him. His revealed Law, “holy, just, and good” as it is (Rom. 7:12; cf. Deut. 4:8; Ps. 19:7–9), mirrors his character, for he “loves” the righteousness prescribed (Ps. 11:7; 33:5) and “hates” the unrighteousness forbidden (Ps. 5:4–6; Isa. 61:8; Zech. 8:17). As Judge, he declares his righteousness by “visiting” in retributive judgment idolatry, irreligion, immorality, and inhuman conduct throughout the world (Jer. 9:24; Ps. 9:5 ff., 15 ff.; Amos 1:3–3:2). “God is a righteous judge, yea, a God that hath indignation every day” (Ps. 7:11, ERV). No evildoer goes unnoticed (Ps. 94:7–9); all receive their precise desert (Prov. 24:12). God hates sin and is impelled by the demands of his own nature to pour out “wrath” and “fury” on those who complacently espouse it (cf. Isa. 1:24; Jer. 6:11; 30:23 f.; Ezek. 5:13 ff.; Deut. 28:63). It is a glorious revelation of his righteousness (cf. Isa. 5:16; 10:22) when he does so; it would be a reflection on his righteousness if he failed to do so. It seems unthinkable that a God who thus reveals just and inflexible wrath against all human ungodliness (Rom. 1:18) should justify the ungodly. Paul, however, takes the bull by the horns and affirms, not merely that God does it, but that he does it in a manner designed “to shew his righteousness, because of the passing over of the sins done aforetime, in the forbearance of God; for the shewing, I say, of his righteousness at this present season: that he might himself be just, and the justifier of him that hath faith in Jesus” (Rom. 3:25 f., ERV). The statement is emphatic, for the point is crucial. Paul is saying that the Gospel which proclaims God’s apparent violation of his justice is really a revelation of his justice. So far from raising a problem of theodicy, it actually solves one; for it makes explicit, as the Old Testament never did, the just ground on which God pardoned and accepted believers before and since the time of Christ.

Some question this exegesis of Romans 3:25 f., and construe “righteousness” here as meaning “saving action,” on the ground that in Isaiah 40–55 “righteousness” and “salvation” are repeatedly used as equivalents (Isa. 45:8, 19–25; 46:13; 51:3–6). This eliminates the theodicy; all that Paul is saying, on this view, is that God now shows that he saves sinners. The words “just, and” in verse 26, so far from making the crucial point that God justifies sinners justly, would then add nothing to his meaning and could be deleted without loss. However, quite apart from the specific exegetical embarrassments which it creates (for which see Vincent Taylor, The Expository Times, 50,295 ff.), this hypothesis seems groundless for these reasons: (1) Old Testament references to God’s righteousness normally denote his retributive justice (the usage adduced from Isaiah is not typical), and (2) these verses are the continuation of a discussion that has been concerned throughout (from 1:18 onward) with God’s display of righteousness in judging and punishing sin. These considerations decisively fix the forensic reference here. “The main question with which Paul is concerned is how God can be recognized as himself righteous and at the same time as one who declares righteous believers in Christ” (Vincent Taylor, art. cit., p. 299). Paul has not (as is suggested) left the forensic sphere behind. The sinner’s relation to God as just Lawgiver and Judge is still his subject. What he is saying in this paragraph (Rom. 3:21–26) is that the Gospel reveals a way in which sinners can be justified without affront to the divine justice which condemns all sin.

Paul’s thesis is that God justifies sinners on a just ground, namely, that the claims of God’s Law upon them have been fully satisfied. The Law has not been altered, or suspended, or flouted for their justification, but fulfilled by Jesus Christ, acting in their name. By perfectly serving God, Christ perfectly kept the Law (cf. Matt. 3:15). His obedience culminated in death (Phil. 2:8); he bore the penalty of the Law in men’s place (Gal. 3:13) to make propitiation for their sins (Rom. 3:25). On the ground of Christ’s obedience, God does not impute sin, but imputes righteousness to sinners who believe (Rom. 4:2–8; 5:19). “The righteousness of God” (i.e., righteousness from God: cf. Phil. 3:9) is bestowed on them as a free gift (Rom. 1:17; 3:21 f.; 5:17, cf. 9:30; 10:3–11). That is to say, they receive the right to be treated, and the promise that they shall be treated, no longer as sinners, but as righteous by the divine Judge. Thus they become “the righteousness of God” in and through him who “knew no sin” personally, but was representatively “made sin” (treated as a sinner, and punished) in their stead (2 Cor. 5:21). This is the thought expressed in classical Protestant theology by the phrase “the imputation of Christ’s righteousness,” namely, that believers are righteous (Rom. 5:19) and have righteousness (Phil. 3:9) before God for no other reason than that Christ their Head was righteous before God, and they are one with him, sharers of his status and acceptance. God justifies them by passing on them, for Christ’s sake, the verdict which Christ’s obedience merits. God declares them to be righteous because he reckons them to be righteous; and he reckons righteousness to them not because he accounts them to have kept his Law personally (which would be a false judgment), but because he accounts them to be united to the One who kept it representatively (and that is a true judgment). For Paul, union with Christ is not fancy but fact—the basic fact, indeed, in Christianity; and the doctrine of imputed righteousness is simply Paul’s exposition of the forensic aspect of it (cf. Rom. 5:12 ff.). Covenantal solidarity between Christ and his people is thus the objective basis on which sinners are reckoned righteous and justly justified through the righteousness of their Saviour. Such is Paul’s theodicy regarding the ground of justification.

Faith And Justification

Paul says that believers are justified dia pisteos (Rom. 3:25), pistei (Rom. 3:28), and ek pisteos (Rom. 3:30). The dative and the preposition dia represent faith as the instrumental means whereby Christ and his righteousness are appropriated; the preposition ek shows that faith occasions, and logically precedes, our personal justification. That believers are justified dia pistin, on account of faith, Paul never says and would deny. Were faith the ground of justification, faith would be in effect a meritorious work, and the gospel message would, after all, be merely another version of justification by works—a doctrine which Paul opposes in all forms as irreconcilable with grace and spiritually ruinous (cf. Rom. 4:4; 11:6; Gal. 4:21–5:12). Paul regards faith, not as itself our justifying righteousness, but rather as the outstretched empty hand which re-receives righteousness by receiving Christ. In Habakkuk 2:4 (cited Rom. 1:17; Gal. 3:11) Paul finds, implicit in the promise that the godly man (“the just”) would enjoy God’s continued favor (“live”) through his trustful loyalty to God (which is Habakkuk’s point in the context), the more fundamental assertion that only through faith does any man ever come to be viewed by God as just, and hence as entitled to life at all. The apostle also uses Genesis 15:6 (“Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned unto him for righteousness,” ERV) to prove the same point (cf. Gal. 3:6; Rom. 4:3 ff.). It is clear that when Paul paraphrases this verse as teaching that Abraham’s faith was reckoned for righteousness (Rom. 4:5, 9, 22), all he intends us to understand is that faith—decisive, wholehearted reliance on God’s gracious promise (vs. 18 ff.)—was the occasion and means of righteousness being imputed to him. There is no suggestion here that faith is the ground of justification. Paul is not discussing the ground of justification in this context at all, only the method of securing it. Paul’s conviction is that no child of Adam ever becomes righteous before God save on account of the righteousness of the last Adam, the second representative man (Rom. 5:12–19); and this righteousness is imputed to men when they believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God.

Theological Misconceptions

Theologians on the rationalistic and moralistic wing of Protestantism have taken Paul to teach that God regards man’s faith as righteousness (either because it fulfills a supposed new law, or because, as the seed of all Christian virtue, it contains the germ and potency of an eventual fulfillment of God’s original Law, or else because it is simply God’s sovereign pleasure to treat faith as righteousness, though it is not righteousness); and that God pardons and accepts sinners on the ground of their faith. In consequence, these theologians deny the imputation of Christ’s righteousness to believers in the sense explained, and reject the whole covenantal conception of Christ’s mediatorial work. The most they can say is that Christ’s righteousness was the indirect cause of the acceptance of man’s faith as righteousness, in that it created a situation in which this acceptance became possible. (Thinkers in the Socinian tradition, believing that such a situation always existed and that Christ’s work had no Godward reference, will not say even this.) Theologically, the fundamental aspect of all such views is that they do not make the satisfaction of the Law the basis of acceptance. They regard justification, not as a judicial act of executing the Law, but as the sovereign act of God who stands above the Law and is free to dispense with it or change it at his discretion. The suggestion is that God is not bound by his own Law: its preceptive and penal enactments do not express immutable and necessary demands of his own nature, but he may out of benevolence relax and amend them without ceasing to be what he is. This, however, seems a wholly unscriptural conception.

The Doctrine In History

Interest in justification varies according to the weight given to the scriptural insistence that man’s relation to God is determined by Law, and sinners necessarily stand under his wrath and condemnation. The late medievals took this more seriously than any since apostolic times. They, however, sought acceptance through penances and meritorious good works. The Reformers proclaimed justification by grace alone through faith alone on the ground of Christ’s righteousness alone, and embodied Paul’s doctrine in full confessional statements. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were the doctrine’s classical period.

Liberalism spread the notion that God’s attitude to all men is one of paternal affection, not conditioned by the demands of penal law; hence interest in the sinner’s justification by the divine Judge was replaced by the thought of the prodigal’s forgiveness and rehabilitation by his divine Father. The validity of forensic categories for expressing man’s saving relationship to God has been widely denied. Many neo-orthodox thinkers seem surer that there is a sense of guilt in man than that there is a penal law in God, and tend to echo this denial, claiming that legal categories obscure the personal quality of this relationship. Consequently, Paul’s doctrine of justification has received little stress outside evangelical circles, though a new emphasis is apparent in recent lexical works, the newer Lutheran writers, and the Dogmatics of Karl Barth.

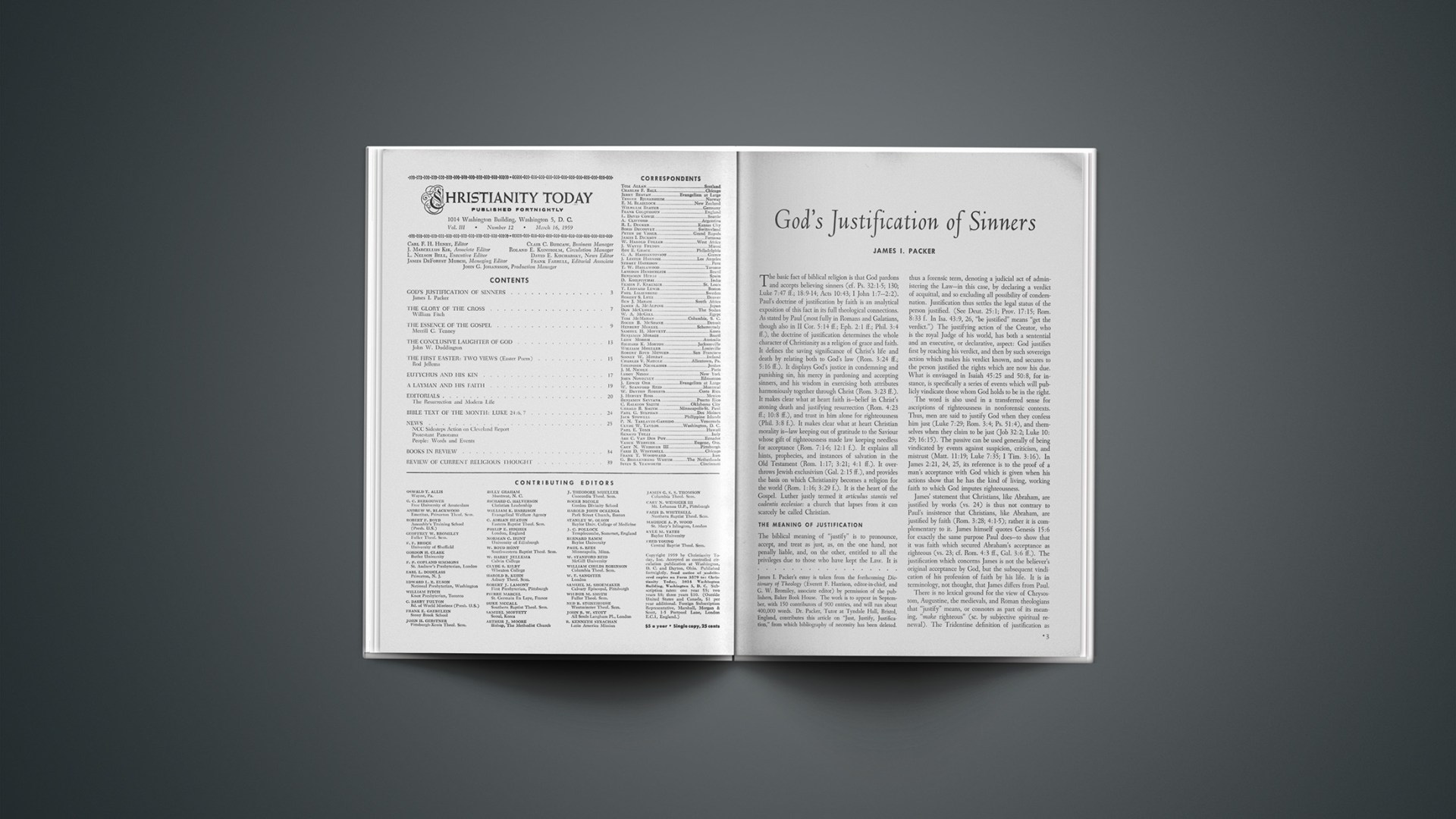

James I. Packer’s essay is taken from the forthcoming Dictionary of Theology (Everett F. Harrison, editor-in-chief, and G. W. Bromiley, associate editor) by permission of the publishers, Baker Book House. The work is to appear in September, with 150 contributors of 900 entries, and will run about 400,000 words. Dr. Packer, Tutor at Tyndale Hall, Bristol, England, contributes this article on “Just, Justify, Justification,” from which bibliography of necessity has been deleted.