Toward understanding the Africaaner.

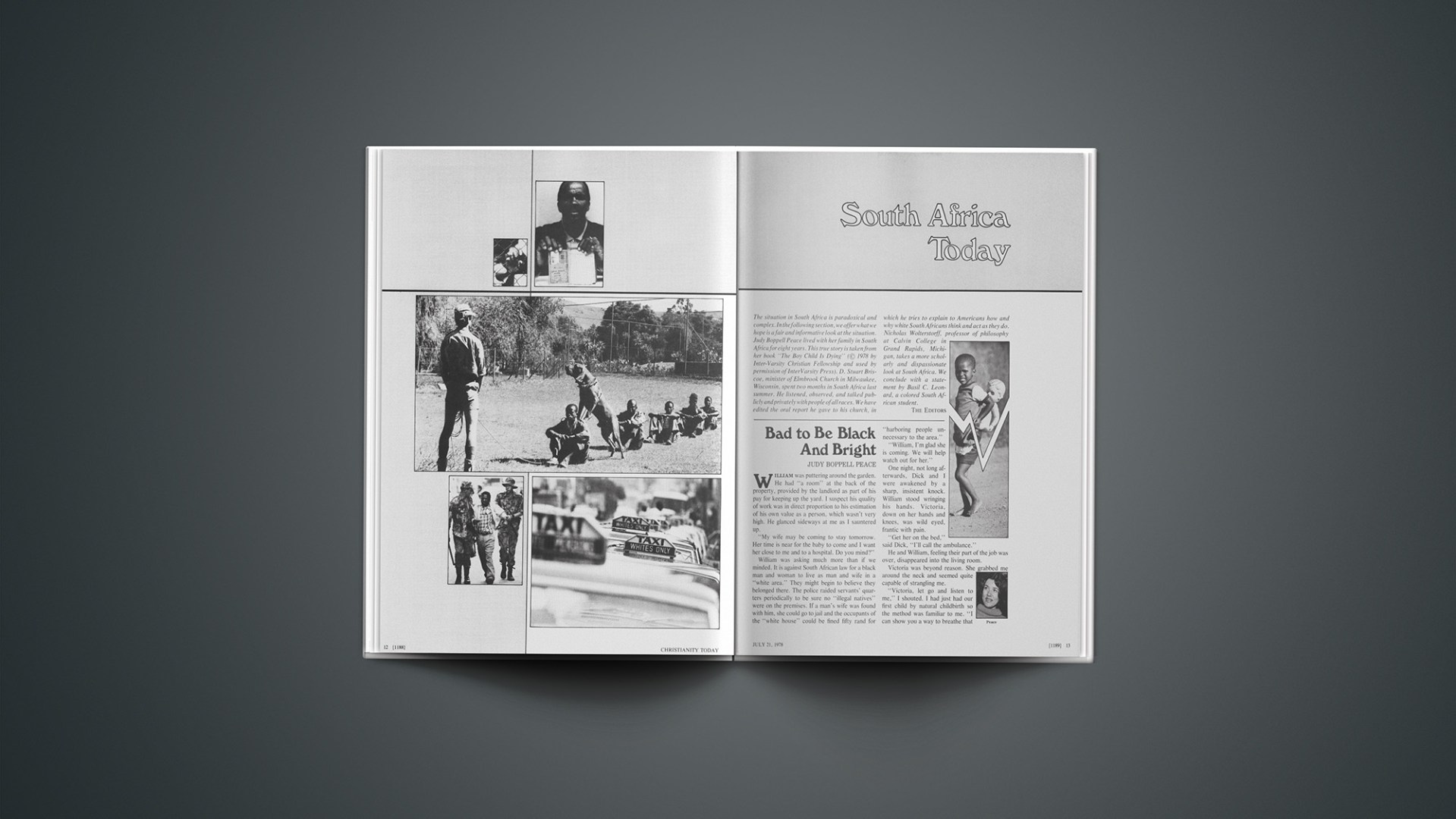

The situation in South Africa is paradoxical and complex. In the following section, we offer what we hope is a fair and informative look at the situation. Judy Boppell Peace lived with her family in South Africa for eight years. This true story is taken from her book “The Boy Child Is Dying” (© 1978 by Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship and used by permission of InterVarsity Press). D. Stuart Briscoe, minister of Elmbrook Church in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, spent two months in South Africa last summer. He listened, observed, and talked publicly and privately with people of all races. We have edited the oral report he gave to his church, in which he tries to explain to Americans how and why white South Africans think and act as they do. Nicholas Wolterstorff, professor of philosophy at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan, takes a more scholarly and dispassionate look at South Africa. We conclude with a statement by Basil C. Leonard, a colored South African student.

THE EDITORS

Bad to Be Black And Bright

JUDY BOPPELL PEACE

William was puttering around the garden.

He had “a room” at the back of the property, provided by the landlord as part of his pay for keeping up the yard. I suspect his quality of work was in direct proportion to his estimation of his own value as a person, which wasn’t very high. He glanced sideways at me as I sauntered up.

“My wife may be coming to stay tomorrow. Her time is near for the baby to come and I want her close to me and to a hospital. Do you mind?” William was asking much more than if we minded. It is against South African law for a black man and woman to live as man and wife in a “white area.” They might begin to believe they belonged there. The police raided servants’ quarters periodically to be sure no “illegal natives” were on the premises. If a man’s wife was found with him, she could go to jail and the occupants of the “white house” could be fined fifty rand for “harboring people unnecessary to the area.”

“William, I’m glad she is coming. We will help watch out for her.”

One night, not long afterwards, Dick and I were awakened by a sharp, insistent knock.

William stood wringing his hands. Victoria, down on her hands and knees, was wild eyed, frantic with pain.

“Get her on the bed,” said Dick, “I’ll call the ambulance.”

He and William, feeling their part of the job was over, disappeared into the living room.

Victoria was beyond reason. She grabbed me around the neck and seemed quite capable of strangling me.

“Victoria, let go and listen to me,” I shouted. I had just had our first child by natural childbirth so the method was familiar to me. “I can show you a way to breathe that will help the pain. You can control yourself and make this a lot easier!”

We both felt desperate enough to try anything and before long she was huffing and puffing regularly.

The baby arrived as the ambulance pulled up. We were greatly relieved, for the baby was born still encased in the sack and neither Victoria nor I were sure of what to do.

“Thank God you’re here,” I said to the two white men at the door. “The baby has been born, but something is wrong. We need your help.”

“If the baby is born, we’ll be leaving, lady. Our orders were just to pick up a woman in labor!”

“Do you know how to save that baby?” I asked.

“That’s not the question, lady. You see, legally, we were called to take a black woman in labor to the hospital and—”

“I don’t care about legalities. If you don’t get in there and help that baby, I’ll have it in every paper in South Africa and America that you two are murderers.” This I said very quietly, as I blocked the door with my arm.

Once the baby was out of danger, the men agreed to take Victoria and the baby to the hospital where the cord would be cut, as they did not see this as their responsibility. I wrapped the baby up for protection against the night air. The men refused to touch her once they had dealt with the sack. As they carried the stretcher out, one of the men turned to me and said, “You must be new to this country, lady. Your attitudes will change!”

I sat deep in thought for a long time after they left. It was hard for me to believe what had just happened. I think I had always felt it was instinctive to save a baby’s life if you could, but these men had not wanted to.

Late in the morning I answered a knock at the door to find Victoria standing there with her baby.

“What are you doing here?” I asked.

“The hospital was too crowded. I was lying on the floor in the hall. I was hungry and no one had fed me, so I walked home,” she said. The black hospital was about a half hour’s drive from our house.

A year later I again opened the door to discover Victoria standing there. She had come to show us Tandi, a beautiful bright one year old.

“Victoria, she is so bright,” I said.

“Yes, isn’t that a shame,” she replied. Victoria knew that to grow up bright and black in South Africa is to live a life of perpetual pain and frustration.

It All Goes Back to The Battle of Blood River

D. STUART BRISCOE

As I see it, South Africa is startlingly unique among all nations of the world. It claims boldly to be a Christian nation.

That’s not unique, you say. America makes the same claim.

No, America doesn’t. America claims only to be a godly nation. On our coins we engrave the words “In God We Trust” but not “In Jesus Christ We Trust.” And there’s a big difference between claiming to be a God-trusting nation (without even defining God), and claiming to be a Christian nation.

To give you a little idea of other sorts of things you experience in South Africa, consider this. They got television only two years ago. And when they watch TV, the first half of an evening’s programming is in English; the second half is in Afrikaans. That’s the night. The next night they reverse the order.

Here’s another, more interesting fact. Every day the first item televised is Bible reading and prayer. And the last thing on at night is an epilogue presented usually by a thoroughly evangelical minister of the Gospel. Thus, each day of nationally controlled television presents the Gospel.

Not only that. South African schools have compulsory religious education. I grew up in England under a system in which I suffered from such a practice, where it doesn’t matter whether the teacher is an atheist or a Buddhist or nothing at all; he teaches religion because it’s his job. At best he gives an inane talk on comparative religion; at worst he gives something that destroys the tenets of the Christian faith. But not in South Africa. There the stipulated objective of the compulsory religious education courses is “that young people may come to know Jesus Christ as their Lord and Saviour.”

I also learned to my utter amazement that young men drafted into the South African Army are taught that in order to lead a disciplined life they must make time for daily prayer and Bible study. Quiet time is built into the South African soldier’s daily schedule.

I doubt that you’ve read or heard these things. But this nation, which is experiencing tremendous social problems, does all of them. I don’t know of another nation that does.

It seems to me that if there is a professedly Christian nation in the world, and if the rest of the world is taking a long, hard look at that nation for whatever reasons, every Christian ought to do the same. Any Christian might have to answer some tough questions about such a nation.

I spent two months in South Africa. During that time I spoke to thousands of people. I found white South Africans eager to discover more of what the Word of God says. I found them deeply concerned about the situation of their country. And I found that they feel deeply hurt by the attitudes of Westerners toward them and their nation. Frankly, they just don’t understand our attitude.

“Why is it,” they ask, “that America and Britain and many other Western powers are so friendly to the Communist nations with whom they have nothing in common and so hateful toward those with whom they have so much in common?”

Despite their bewilderment, they were eager to find out what God might be saying. I tried to examine just what Scripture really is saying, and sought to apply it to the contemporary situation.

At this stage, it’s painful for white South Africans to examine their situation in the light of Scripture. It’s far easier to examine Scripture in the light of your own prejudices. But it’s a much nobler thing to examine your prejudices in the light of what Scripture says. By and large, I found my listeners ready to engage in this more difficult kind of examination.

During my visit I had access to all racial groups. The meetings were integrated. If that had not been the case, I would not have gone. But before I went they made it clear that every person would be free to attend; throughout the weeks there was absolutely no problem with apartheid.

Now let me try to give you some details about the South African situation. First, the political. You can’t talk with anybody without getting political within twenty-three seconds. With the best will in the world you say to yourself that you’re not going to talk politics, but there’s absolutely no way to avoid it.

White South Africans say, “Listen, we were here first. This is not a colonizing situation. We were in South Africa long before the black people ever came.

“Our history,” they say, “is not like America’s. What happened in America? The British went in and practically exterminated the American Indians—and then brought in slaves. But we never exterminated anyone or brought in any slaves.”

As with everything else, it just depends on who’s writing the history. In certain South African caves archeologists have discovered wall paintings and carvings of Negroid people that date back to the fifth century. Some people are happy to know that. Others don’t want to know it at all.

There is no question that black people had not arrived down in the Cape when the Dutch settlers first arrived in 1652. Yet at the same time I have no doubt that black people were in the northern areas of Transvaal, possibly in the Orange Free State and parts of Natal before the whites ever got there. So the argument of who came first is deadlocked.

In 1688 the French Huguenots arrived. (Perhaps their greatest contribution to South Africa was showing how to plant vineyards.) But 115 years later, in 1803, a momentous occasion took place: The British took over. Now, while the Dutch were farming and having their problems with the Hottentots, and while the British were busy taking over, something else was happening—a tremendous migration from the north of the Zulu tribe.

Among the Zulus was a warrior called Chaka. Chaka was a remarkable man. Chaka was able to round up the Zulus and make them a mighty nation of mighty warriors.

The Dutch couldn’t get along with the English. The Dutch, of course, resented the fact that though they had arrived first the English had not come in and taken over. In 1835 what’s known as the Great Trek took place. In the Great Trek, one-fifth of the population of the Cape Province headed north to escape the hassle.

Others who had already headed north ran into a black tribe whose name is spelled X-h-o-s-a (pronounced O-cl-sa. The first record of those white migrants’ contacts with the Xhosas says, “We met some black people who cluck like hens”). The trekkers ran into the Xhosas, the Zulus—and into fierce battles. This may seem irrelevant, but it’s very important in deed. In 1838 a tremendous turning point came in South African history: the Battle of Blood River took place.

A group of the Dutch (Afrikaans) trekkers moving up from Cape Province, feeling hurt that they had to leave what they felt was theirs, and looking for new territories ran straight into the Zulus. The Zulus came against them by the thousands, but the trekkers positioned their ox wagons in a circle, a laager. Within the laager, their women loaded the guns and the men kept firing. The result: Thousands of Zulus were massacred, and three—only three—trekkers were killed.

The trekkers’ explanation for their action was that the Zulus had earlier massacred a little group of their people. The river near there became known as Blood River because, according to reports of that 1838 battle, Zulu blood made the river run red.

Neither the blacks nor the whites have ever forgotten the Battle of Blood River. In South Africa today there is terrible distrust. In many areas there’s bitter hatred between the two. And it stems from the atrocities of blacks on whites and whites on blacks.

I am convinced that you can adequately understand South Africa’s present situation only if you take time to read its history. You need to know, for example, that in 1860 the British brought in some natives of India to work in sugar cane plantations and factories. Those Indians were 83 per cent Hindus, 12 per cent Muslims, 5 per cent Christians. Since then, these Indians have multiplied to 700,000. And today they’re 83 per cent Hindus, 12 per cent Muslims, 5 per cent Christians.

In 1899 the Boer War took place. Boer is the Afrikaans word for farmer. Those farmers were rough-tough characters, who fought to their dying days. Remember that, because it is from the Boers that the Afrikaans mentality comes. In one of the Boers’ fights with the British, one of their prisoners was a fellow named Winston Churchill. Churchill managed to escape to a place called Pietermaritzburg.

The Union of South Africa came into being in 1910. Immediately the government decided to have two official languages, English and Dutch. No tribal languages. To keep both the English and the Dutch happy they decided to make Cape Town the seat of parliament, Pretoria the seat of government, and Bloemfontein the seat of the Supreme Court. The Dutch and the English had little time for each other. Neither was going to learn the other’s language. And the four provinces had always an uneasy alliance with each other. From the beginning, deep-rooted differences have separated the people of South Africa.

As soon as the Union was formed, more developments began to take shape. In 1913 the Native Land Act proclaimed that a certain large portion of the land was “inalienable Bantu land.” Bantu is the word the whites use for the blacks. Since then, those areas of South Africa have remained the possession of the Bantus. The Labor Act (1926) defined two kinds of labor: civilized and uncivilized. Civilized labor was that done by people who conformed to European standards. And uncivilized labor was done (I quote) “by people who are barbarous.”

In 1948 the National Party came to power, and it’s remained in power. When they call a new election the only question is, By how much will they increase their majority? The official policy of the Nationalist Party is what they call apartheid—an Afrikaans word meaning apartness or separateness. The man who propounded the theory of apartheid above all others was Dr. Daniel Malan, who eventually became prime minister. According to Malan, “Apartheid is the only way that justice can be done for all the peoples of South Africa.” In a nutshell you can describe the apartheid policy like this: “There are white people and black people. The whites will govern the whites; and when the whites can allow the blacks to govern the blacks, they will. But blacks must never govern whites.”

The most puzzling thing about that policy is that it stems, according to those who propound it, from calvinistic theology! God is free to do whatever he chooses to do. The apartheid people’s twisted application of this is that God in his infinite wisdom chose to make white people and black people and that each is totally different. Therefore, to try to make the two races anything but totally different is to fight against the sovereignty of God.

They go even further. They tell you that God made the whites superior to the blacks. Using Scripture passages about God’s establishing the bounds of man’s habitation and about how a particular race should be to Israel the drawers of water and the hewers of wood, they say that egalitarian nations are going against the plan of God.

The National party encountered no difficulty establishing apartheid in 1948. In 1949 it disen franchised the Indians, who previously had had voting rights. In 1950 it passed an act saying that any sexual activity between whites and nonwhites was illegal and punishable by immediate imprisonment. And that year they also passed legislation to classify whites, blacks, coloreds (those of mixed races), and Asian people. Everybody was registered. At the same time they passed the Group Area Act, which assigned certain regions for the people of each racial group.

By that act, if you’re black you must carry your certification of blackness with you at all times, and you can never live in a nonblack area. If you’re white, of course the white areas are open to you. But you cannot live in any other area, nor would you want to, because the areas reserved for whites are far superior to the others.

In 1961, when the British government pressured South Africa to change the policy the country left the British Commonwealth. Two years later it passed a number of acts that give the South African minister of justice authority to detain anybody suspected of “Communist activity” for a period of up to 170 days without any charges and without letting anybody know where he was. Thousands of people have been imprisoned under this act. Nobody knows just how many, but the Encyclopedia Britannica uses a figure of three quarters of a million people.

In addition to this power, the minister of justice can place under house arrest whomever he feels is endangering the State. He can also place a five-year ban on any such person. Under it, the person may receive no visitors; he cannot be quoted; and he must report to police at least once a week. The rationale behind all this is that anyone considered subversive to the state must not be allowed to threaten the State. So any suspect is whipped off, put under ban, or put under house arrest.

An aspect of the Nationalists’ grand plan is what they call the homeland policy. According to this, apartheid will achieve its glorious fulfillment when all black people have been put into their own tribal areas, given total rights to those areas with freedom to govern their own affairs, and finally given their independence there. When that has happened the independent black nations in the prescribed areas will be free to join in some kind of federation if they so desire. To date, two homelands have arrived at that stage of independence, Transkei and Bophuthatswana. Nobody else has recognized their nationhood yet, except the South Africans, and considerable confusion surrounds the whole situation. But they’re going ahead with the policy.

Probably the next in line is Ciskei. I visited Ciskei. I found a number of believers there who were working carefully with the leadership of that emerging nation (or whatever you may want to call it) and were firmly convinced that independence is the way to go. So the idea of separate development is that the only way blacks can really have a chance in South Africa is to be given their own areas and to go their own way. If you try to integrate them with whites, they just can’t compete.

It’s difficult to shake white South Africans in that belief, or to get them to admit that if the blacks had equal opportunity and encouragement, maybe they could function better. The whites will not listen to such talk. I think many of them are absolutely sincere in their belief that it’s in everyone’s best interest to live peacefully but always separately. Tragically, it isn’t working.

A second reason for South Africa’s apartheid legislation is their inordinate fear of communism. That nation says, “If you’re going to be a Christian you’ve got to be anti-Communist.” To a certain extent they are rather like extreme right-wingers in America who seem to want to prove their Christianity by their anticommunism. South Africa emphasizes that it is a Christian, anti-Communist country. They see Communists all over the place. With some justification they say, “What on earth are the Western powers playing at? Can’t they see what happened in Angola and in Mozambique? You sit in the United Nations and debate, but the Communists are taking over Mozambique on one of our borders. And what are they trying to do in Southwest Africa? Don’t you understand that as soon as we pull out of west Africa the Communists will be on both our east border and on our west? Look at Europe. Europe’s gone. Look at North America. It’s going. We are the last bastion of anticommunism. We’re the last bastion of those who will stand for Christian truth. We’ve got to stand firm against communism.”

Third, there’s no question that the Nationalists, the Afrikaaners, take great pride in their history. Any nation should take pride in some parts of its history. But in South Africa you find what is known as the laager mentality. They say, “Please go back to America and tell those two prize idiots, Carter and Young, that they’re going exactly the wrong way about things. Because the more they close in on us the more we’re going to go into our laager; and the more we go into our laager the tougher we’ll be. We’ll fight to the last drop of blood. We’ll never accept anything other than separate development.”

Notice the statistics. South Africa has 4.6 million whites. It has 2.4 million coloreds. It has 8 million Indians. The Nationalist Party is now taking steps to get the coloreds and the Indians to join them on apartheid policy. If that should happen, they would add up to more than 7 million. But how many blacks are there? Eighteen million.

The people in power are outnumbered and they know it. Projections for the year 2000 indicate 35 million blacks, 6 million whites, 6 million coloreds, and perhaps 2 million Indians. That’s 14 million against 35 million. But the whites say, “Yes, Africa is against us, the world is against us, but we’ll not allow those Communists to infiltrate our situation.” Just recently the foreign minister said, “We’ll fight them like cornered, trapped animals.” That’s the mentality of South African whites.

What about the blacks there? A delightful black believer with whom I had fellowship said, “I loathe and detest apartheid. It is contrary to everything I know about God. It is in flat opposition to everything I know of Jesus Christ. It’s in complete opposition to what the Church of Jesus Christ stands for. I hate it as much as I hate violence.”

That man lives in Soweto. Now the very name Soweto is demeaning. It’s an abbreviation for South-West Township, an allotted area for blacks near Johannesburg. Soweto is where that man and (by government statistics) 1.5 million other blacks are required to live. Residents of the area say that nearly 3 million make their “homes” in that area.

The urban blacks are understandably restless. “Even supposing that the practice of apartheid might work for people who still live out in the rural tribal areas,” they say, “what on earth do the authorities think they are going to do with the 6 million blacks who are crowded into the city areas, who have never even seen the rural areas? Are they going to try to ship us out there?” Proponents of apartheid have never really addressed their theories to the plight of the urban blacks.

Talk to whites about this and they simply say, “Well, it’s the Communists. The Communists are stirring up trouble.” The whites seem unable to understand that while unquestionably Communists are active, they can be active only where there are areas in which to act. Whites don’t seem to understand how they are humiliating the blacks. Nor do they seem to understand that most blacks are not like their stereotypes. It almost seems that the whites don’t want to know.

So black believers find themselves in a very tricky situation. If they stand up and speak for what they believe Christ wants them to say, they’re branded by many whites as Communists. And if they do not stand up and speak in the name of Christ they are rejected by other blacks who say, “Jesus Christ would not have tolerated such a situation. Jesus said he came to preach deliverance to captives. Jesus Christ said he came to emancipate the oppressed. What’s happened to your Jesus? What’s happened to your church?”

South Africa’s black believers are caught in a vise. They desperately need our prayers. They desperately ask for our prayers. I spent a lot of time with those believers and I want to tell you they’re not Communists. I want to tell you they’re not stupid. They’re brave and beautiful believers in Jesus Christ.

Did you read about the crackdown in Soweto? Did you read how all the black newspapers were closed down? Did you read how many people were banned? And did you read how many churches and Christian organizations were raided at dawn? Every one of the believers with whom I spent time and had beautiful fellowship most likely were under surveillance by the secret police. Even while I was there a number of believers told me quite frankly, “We know our phones are tapped. We know as soon as we have a visit from a certain person that immediately afterwards we’ll have a visit from the security police. They track our every move.”

Getting away from all the ideologies, and getting down to the human level, you find prejudice, distrust, hatred. And I haven’t even talked about the coloreds or the Indians. In many ways those people are in an even more pitiful position than the blacks, because there’s no homeland for them. The British brought the Indians over from their Asian homeland, but the British aren’t about to take them back there. And there’s no homeland for the coloreds because the coloreds are an absolute embarrassment. You see, the coloreds are products of the good old calvinistic burgers doing some things they should not have done with the young women of Malaya and Singapore, whom they brought to South Africa to work, and with the Bushmen, Hottentots, and Bantu.

Where does the church fit in all this? The church is supposed to be a unique society. It is supposed to build bridges where the rest of society erects barriers. The church is to be a place of repentance and faith—a society in which people who have come to the foot of the cross and called sin sin, have repented of it, and have been forgiven by the blood of Christ are one.

You find all sorts of people kneeling at the same cross—black ones, white ones, colored ones, yellow ones. All have two things in common: they are sinners, they are redeemed. How can you kneel at the foot of the cross to receive redemption from sin and then have nothing to do with the sinner next to you, who is experiencing the same redemption?

Although I understand the immense problem confronting the nation of South Africa, and although I have no easy answers, one thing I do know is that the church needs to be in the midst of this appalling confusion. The church needs to be a living witness to what it is to be a community of redeemed sinners—a community that in its love for Jesus Christ loves all others who love him. I met many believers of all races who are committed to this concept of the church and who are endeavoring to make it work even when it sometimes leads them into danger.

It’s time for all God’s people to say honestly and genuinely, “I am your brother; you are my brother.” And not just to say it, but to engage in activities that demonstrate it.

I suspect that if our own situation in America ever gets as much pressure upon it as theirs has, we’re going to be much like they are. Then it’s going to become evident to a secular, cynical, hostile society that we Christians are really not much different from anybody else.

The church is intended to be the mouthpiece of God. Well, God’s Word speaks of justice and righteousness. When the church sees injustice on its doorsteps, it had better speak out.

Curiously, the church in South Africa is just now experiencing a remarkable renewal movement, charismatic in nature. Churches that had been quite cold and dull are now popping. Some of the people like the popping and others can’t stand it, but popping they are. Some churches feel threatened by this development. Others welcome it.

The young and older believers are also divided. One older believer said he was certainly going to vote for the Nationalists; and I heard that man’s two young sons say, “Father, we are shocked beyond understanding. We cannot understand how under any circumstances you can live with your Christian conscience if you do such a thing.” Totally divided. This is the story of South Africa. It’s a nation divided, with a church divided, in desperate need of a mighty touch of God.

Can Violence Be Avoided?

NICHOLAS WOLTERSTORFF

Early on the morning of last October 19 the police and security officers of South Africa, under orders from Minister of Justice James T. Kruger, fanned out across the country, banning some eighteen black organizations, banning the country’s largest black newspaper, The World, arresting its editor, arresting some fifty other people, banning the editor of The Daily Dispatch, banning the Christian Institute and its courageous leader, Dr. C. F. Beyers-Naude—with none of these actions being at any point whatever subject to judicial review.

This all happened two months and a day after Steve Biko, the gentle and sensitive leader of a black consciousness movement called the Black People’s Convention, had been arrested without warrant and detained without charge, and a month later was found dead in his cell. After offering a series of other explanations for Biko’s death, the government eventually admitted that he died of massive brain damage, supposedly self-inflicted. At the subsequent trial it was revealed that Biko had been chained naked in his cell for days on end.

What is going on in South Africa? What accounts for these gross travesties of justice, inflicted by a government that calls itself Christian?

People in South Africa often talk about the “complexity” of their problems, sometimes using this “complexity” to justify inaction on their part toward the solution of those problems. And the situation is indeed complex. In particular, it cannot be understood simply as a case of racism such as we experience in this country. We can grasp the essence of the problem, however, if we can understand something of the nature of the Afrikaaner character, something of why the Afrikaaner has implemented the policy of apartheid, something of how that policy is implemented, and then something of the current mood among the blacks.

The original white settlement in South Africa occurred in 1652, when Jan van Riebeeck and some followers settled on the tip of southern Afica as representatives of the Dutch East India Company. The Afrikaaners are descendents of those original Dutch settlers, plus later Dutch immigrants, and later Huguenot immigrants. Thus the Afrikaaners can trace their ancestry back in South Africa almost as far as Americans can trace their ancestry back in the United States. The Afrikaaners are colonialists in Africa no more and no less than Americans are colonialists in America.

The history of the Afrikaaner, from the eighteenth century onward, is the history of a long series of painful, often brutal, entanglements—with the British, who for centuries were determined to have South Africa as part of their colonial empire, and with the blacks, whom the Afrikaaners met and battled at various points as they kept traveling north to escape the British. It was in the crucible of this often painful history that the character of the Afrikaaner people was forged.

Here is not the place to attempt a full description of that character. A few features are crucial, though, for understanding the present situation. Most important is the intense Afrikaaner sense of peoplehood, of folk-identity. The Afrikaaners are bound together by a more intense bond of folk-identity than almost any other people on the face of the globe today. They are, if you will, a “tribe.” Nothing in our experience enables us North Americans to understand their deep and passionate sense of identity. So intense are their feelings on this matter that those who depart significantly from the convictions of the Afrikaaner people are first ostracized, and then eventually branded as traitors. I have already mentioned Beyers-Naude, the courageous leader of the Christian Institute. Beyers, though an Afrikaaner who can trace his Afrikaaner ancestry back for centuries, has for more than a decade now publicly opposed the policy of apartheid. I shall never forget another Afrikaaner, sitting in my living room in Grand Rapids, discussing Beyers with me, and at the end of the discussion saying, with intense passion, “Beyers is a traitor.”

Secondly, the Afrikaaners as a whole have a fierce sense of independence. Having fought off the British for centuries they are determined that no one will tell them what to do—no foreigner, but also no one in South Africa. They are determined that they and they alone will determine their destiny. They are determined that they and they alone will identify their country’s problems, that they and they alone will decide what the solutions will be, and that they and they alone will decide when and how those solutions are to be implemented. Their government frequently adds, “All grievances will be investigated and will be eliminated where justified.” But what it means thereby is that it will decide which grievances to investigate, and that it will decide which grievances to eliminate.

Thirdly, the Afrikaaner has a passionate love of order, a passionate fear of disorder. This appears, for example, in the structure of Afrikaaner society, which is profoundly hierarchical, from the top down, with old people having enormous power. And there is great attention to ceremony and ritual. The structure is like that of Northern European society up to, say, seventy-five years ago. Those near the bottom of the hierarchy are regarded, in paternalistic fashion, as children who must be shaped and formed and developed until some of them are one day capable of filling the top slots. And all the blacks together are explicitly spoken of as children, with the “father” of these “children” being thought of as one of those old-fashioned parents who rarely thinks in terms of the rights of the child but only in terms of the need to mold and form the child. I have before me the October 19 text of Justice Minister Kruger, in which he attempts to justify the bannings and jailings. Here the word “justice” nowhere occurs, nor any synonym thereof. By contrast, references to law and order occur five times: “endanger the maintenance of law and order,” “endanger the maintenance of public order,” and so forth.

Fourth, the Afrikaaner is a deeply religious people, and more specifically, he is deeply attached to the Christian religion. He is a faithful church-goer, he naturally thinks along theological lines, his public television closes the broadcast day with devotions, and he sees himself, as did our own early Puritans, as a people called by God.

This is by no means a full description of the Afrikaaner character. I have said nothing, for example, of the Afrikaaner’s passionate love for the wide-open prairies, rather like that of the American pioneer of a century ago. But let me move on now to a bit of history.

In the 1930’s some progressive thinkers among the Afrikaaners, as well as some conservative ones, began to reflect along the following lines. They were vividly aware of the general policy of the English, when confronted with diverse languages and cultures, of trying to impose the English language and Anglo-Saxon culture on that diversity. They had painfully experienced that policy themselves when, for example, they had been forbidden to use their own Afrikaans language in their schools. They were, in short, aware of how oppressive a policy of forced “integration” can be. So they began to say to themselves: Wouldn’t it be more liberating to protect and encourage linguistic and cultural diversity rather than flatten it out? Wouldn’t it be more liberating to have a multi-national society in which distinct cultures live side by side? Distinct cultural identity was of course what the Afrikaaner had all these years fought for on his own behalf in the face of the English. But confronted with the sizeable diversity of black tribes within South Africa these intellectuals now envisioned a multi-national society as liberating for the blacks as well. Why not allow each tribe to preserve its own cultural identity? And why not even allow them to dwell on their ancestral land, if that is possible?

Thus was born the vision of separate development, or apartheid, and the vision of the homelands. I do not wish to suggest that its original motivations were entirely idealistic. But I think it important to see that, in its beginnings, it was in some measure idealistic. It was seen as an attractive alternative to the oppressive character of the Anglo-Saxon strategy of forced integration. And it was customarily given a religious grounding: It was said that God, who over the course of history had created many distinct peoples, surely did not want these all destroyed but instead wanted his kingdom to consist of a rich mosaic of diverse peoples, each with its distinct culture living in obedience to the Lord.

Then in 1948, to everyone’s surprise, the dominantly Afrikaaner Nationalist party came into power. It forthwith proceeded to implement this visionary ideology, engaging in a social reconstruction more massive than anything we have seen in our century except for that which has taken place in various countries seized by Communists. In a massive outpouring of legislation the Nationalist Party enacted into law the visionary ideal of separate development, which was first sketched out by Afrikaaner intellectuals in the 1930’s.

Now one can adopt varying responses to this vision of separate cultural development. While recognizing its dangers, and the confusions in the arguments for it, I myself have a good deal of sympathy for it. It seems to me that the policy of forcing one language and one culture on a linguistically and culturally diverse populace has in fact often been profoundly oppressive and humiliating. But what any of us may think of this visionary ideal has by now become by and large irrelevant. For what we are now confronted with in South Africa is a situation in which, ironically, the distinct cultures are all being rapidly destroyed by South Africa’s Western capitalism; and a situation in which the visionary ideal is being implemented with appalling injustice. For what is crucial to see is that the policy in its implementation does not so much encourage the distinctness of various cultures but forces their separateness. Let me be specific concerning some of the injustices.

1. Only the whites in South Africa are given a voice in the implementation of the policy of separate development. One would have thought that if distinct cultures were to be encouraged, then representatives of the distinct cultures would each be given a voice in the formation of the policy. No such thing has happened. Whites, and whites alone, have political voice in the formation of national policy. The blacks have systematically been deprived of all their political rights. For they have been regarded as children, not capable of wise decisions.

2. Secondly, the homelands are in the main not contiguous units of land, but disconnected parcels sprinkled about within white South Africa. One would have thought that if distinct cultures were to be given their ancestral homelands, then at least those lands would be contiguous units.

3. Thirdly, the policy known as “job reservation”—a policy whereby a great many jobs are reserved exclusively for whites—results in grievous inequity. Certain positions are just closed to blacks, regardless of their training and competence. As one might expect, these are by and large the upper echelon jobs. It’s true that certain positions are open to both blacks and whites. But then one comes across another appalling inequity. Almost invariably the blacks are paid substantially less for the same work in the same job than whites. The supervisor of one of the gold mines that I visited told me that for the same work in the same position whites are paid up to ten times as much as blacks. When asked to explain this policy he replied that blacks don’t need as much to live on. The Afrikaaner thinks of his wealthy capitalist culture as built by himself. The truth is just as much that it has been built on the backs of cheap black labor. And what may be added is that in spite of the Afrikaaner’s devotion to the family, the “pass laws” in South Africa are such that often a black laborer has to be separated from his family for months and months at a time. Systematically the laws destroy the black family.

4. The so-called “coloreds” in South Africa are mulattoes, mainly descendents of the children resulting from interbreeding between the original Dutch and Huguenot settlers, and blacks. Most of these coloreds have been Afrikaaner in culture and language for centuries. Yet, while earlier they had the right to vote on national affairs, they too have now been deprived of that right. Thereby the racism that is mixed-in with the visionary ideal is revealed. For though the culture of the coloreds is “right,” being Afrikaaner, their skin color is wrong.

5. Lastly, a word must be said about the detention laws in South Africa. In the “Terrorism Act,” for example, one finds first an extremely broad definition of “acts of terrorism,” including actions that none of us would ever dream of regarding as acts of terrorism. And then there is a provision that says that a police officer of the rank of lieutenant-colonel or above may arrest without warrant for purposes of interrogation anyone whom he suspects of violating the terrorism act. The person may be held incommunicado for as long as the police and security officers wish, without a charge ever being filed against him, without the public ever being notified where he is being held, without the prisoner ever being given access to an attorney, and without any of these actions at any point being subject to judicial review. It was under such a detention provision that Steve Biko was detained. These provisions are not part of some special legislation to be put into effect in declared states of emergency. They are part of the normal legislation in South Africa. What one sees at this point is one of the characteristic signs of a police state.

My list could go on. But my point has been made. Whatever one thinks of the vision of separate development and distinct homelands, the policy has been implemented with appalling injustice. And that is the situation confronting us today.

It is regularly said in reply, by Afrikaaners and even by Americans, to charges such as these that the blacks “have it better” in South Africa than anywhere else in Africa. And it is added that even the blacks know this, as is evidenced by the fact that they are continually coming in from other African countries to work in the gold mines and other enterprises. My answer is two-fold. How could the fact that the blacks have it better in South Africa than elsewhere in Africa possibly be a justification for wreaking these appalling injustices upon them? Can one ever excuse injustice by observing that other people are still worse off? And secondly, how can a Christian possibly adopt the materialist notion that the criterion for “having it better” is having more pay? When the black man’s family is destroyed but his paycheck is larger, is that “having it better” by any defensible Christian standard? When his leaders are arrested without warrant but he makes more money, is that “having it better” by any defensible Christian standard? Would the Afrikaaner himself ever regard that as “having it better”? Has he himself not been willing historically to put up with great hardship for the sake of his rights?

I have talked so far about Afrikaaners, their character and their policies. And I have talked about them at length, for it is difficult for an American to understand them. But what is of equal importance in the dynamics of contemporary South Africa is the rapidly increasing phenomenon of black consciousness. More and more the blacks are beginning to think of themselves not primarily as members of separate tribes but as united in their blackness. And more and more they are refusing to feel humiliated on account of their blackness. More and more they are beginning instead to feel proud of being black. And more and more there is rising among them a steely determination to secure their rights, if possible peacefully, if necessary with violence—as indeed the Afrikaaner has historically fought violently for his rights. Although their articulate leaders are systematically banned and arrested, yet this black consciousness grows apace. And whereas five years ago the blacks might have been willing to settle for something less than majority rule, in the judgment of most observers majority rule is now the least of their demands. I think there is no chance whatsoever of this black consciousness diminishing; all it can do is increase.

And so the nature of the conflict is starkly clear. The Afrikaaner is determined that he and he alone will decide the future course of South Africa, and at this point he is determined that that future will include apartheid. In particular, he is trying by every means to avoid granting full political rights to the urban blacks. Improve the conditions of the urban blacks, yes. Grant certain rights to the homeland blacks, yes. But political rights to the urban blacks? Never. At the same time the urban blacks are more and more determined to secure their political rights and to have a voice in South Africa’s future. Thus there are now in South Africa two immense forces on collision course.

One can easily see the strategy that the government is following. The government is willing to allow blacks and whites to talk as much as they want—to chatter. “Talk is cheap.” And so it says that South Africa has a free press. But as soon as a movement arises that bears the promise of developing in such a way that the situation in South Africa will be significantly reshaped, the government will do all it can to snuff out that movement. That is what accounts for the arrests and the bannings. The government believes that apartheid is a God-ordained, liberating, policy, and that the blacks in South Africa have it good and know they have it good. Consequently it sees unrest as due to Communist and anarchist agitators, or “dupes” of these. And it does whatever it deems necessary to snuff out such unrest and to restore “law and order.” It is willing to postpone justice to that indefinite day in the future when all is nicely in order.

Those Who Are Left Behind

It is winter time and it is raining heavily in one of the most picturesque cities of the world—Cape Town.

Three people stand at a bus stop, all getting soaked. A bus comes along, but unfortunately the upper deck is already full. The white traveler gets on and leaves two people stranded, even though the bus has half of the lower deck empty.

We who are left behind don’t say a word. We have grown so accustomed to it that it doesn’t bother us any longer; anyway, we speak different languages. The silence continues.

In the articles on South Africa in this issue much has been said about the whites and the blacks, with the coloreds mentioned briefly. This is a sure reminder of treatment received in South Africa. So much is done to keep the white in power and the black out of the ruling quarters; the colored finds himself ignored.

Americans love to talk about their heritage. Yet the colored population has not had this chance. There are several theories about their origin. A white South African will accept Stuart Briscoe’s explanation: Dutch plus women from Malaya and Singapore, whereas another group would claim it to be Dutch plus black (with Bushmen and Hottentots as well). South African whites reject the latter because it ties them in too closely with a people they are unwilling to accept.

Most of the factory workers, mechanics, carpenters, general tradesmen, and artisans come from the colored population. Realizing the abilities of the coloreds, the “very kind” government has been making available jobs that before were only for whites. All of these changes are usually widely broadcast. But no one mentions the vast differences in wages and salaries between whites and coloreds who hold the same jobs. The government justifies its position by the absurd argument that the cost of living of the nonwhite population is lower and yet we have to buy from the same stores and fill up at the same gas stations.

Why is the colored squeezed into this position of helplessness? The reasons are many and deep-rooted, but can be summarized as follows.

Many coloreds are fair-skinned and would definitely not be recognized as colored in the United States, whereas others have darker complexions and would be called black by Americans. The former group finds it much easier to identify with the whites, but they are rejected; the latter group would identify more easily with South African blacks, and yet they too are rejected as not being truly black. The third section of the colored group does not identify with either side, but yet has to live with both groups. This makes people hesitate to trust each other. Economically and educationally coloreds have been granted more opportunities than any of the other minority groups in South Africa, but we have been denied political rights.

Politically, the Vorster party has organized a Colored Representative Council (CRC). This play-parliament lets some great colored politicians come together and discuss the future of their people. And that’s all they do. This organization has little or no power.

The colored people are greatly divided among all mainline denominations as well as many independent churches. The biblical teaching in many of these churches is shallow since their ministers have not had the opportunity of a seminary education.

Where do you begin to explain the social situation of South Africa to a nation like America that has been endowed with so much freedom?

BASIL C. LEONARD

Basil C. Leonard is a member of the colored group in South Africa. Presently he is a student at Trinity seminary and is preparing for a ministry in South Africa. The hope of the South African church lies in the hands of talented young evangelicals like Basil—colored, white, and black.

I do not know whether South Africa can avoid conflagration. Its chances of doing so are steadily diminishing, for reasons I have tried to explain. What slim hopes there are for avoiding conflagration seem to me mainly to lie in the Christian consciousness of the religiously conservative of the Afrikaaners. These are people of the Bible. And its prophetic liberating message still speaks to them, albeit in heavily muffled fashion. Especially some of the younger intellectuals among the religiously conservative Afrikaaners are at this point intensely anguished. They are now being pulled in two between their loyalty to Christ and their loyalty to their people. Their anguish is the anguish that St. Paul felt when he had to choose between Christ and his ancestral people.

Last November a remarkably courageous document called “The Koinonia Declaration” was issued, signed by some blacks, some English whites, and some of these religiously conservative, young Afrikaaner intellectuals. The main points of the declaration were printed in the January 27, 1978, issue of CHRISTIANITY TODAY. In characteristic fashion, sufficient pressure was applied to these signers to destroy any possibility of a movement arising from the issuance of this declaration. And yet my guess is that the agonized alteration of consciousness that is taking place among these young Afrikaaner intellectuals is something that cannot any longer be reversed. I think the question now is when they will be granted courage sufficient to express their convictions and suffer the profound alienation from their people that is bound to come their way.

What can we as North American Christians do? Not much, other than to speak clearly the call of the Gospel. Remind the Afrikaaner of God’s call for justice. Call his attention to the grievous injustices that he is wreaking and the rampant statism that he is practicing, and pronounce God’s work of judgment upon them. Insist that American corporations either leave South Africa or treat their nonwhite employees with dignity and equity, in defiance of the practices of apartheid. And stand on the side of that suffering mass of humanity in South Africa—the blacks. Listen to them. Speak on their behalf. And never forget that millions and millions of them are fellow Christians who along with us are part of Christ’s body. Painful as it is to see, what we are witnessing in South Africa today is not white Christian pitted against black pagans. We are witnessing white Christians oppressing black Christians. We are witnessing Christ’s body engaged in internal strife, torn and bleeding.

Identify the infection. Speak the healing word. Bind up the wounds. And pray that the Lord who came to bring freedom to the captives and light to those who sit in darkness in the shadow of death may send his Spirit upon this beautiful land, with its multitude of immensely vigorous, generous, and likeable persons, so that the agony of its people may be lifted—the agony of the blacks who suffer at the hands of the whites, and the agony of the whites who suffer at the hands of their own desperate fear of what would happen if.…