Amid charges of mismanagement, intolerance, and adultery, The Way International—considered a cult by some—appears to be deteriorating. Over the past year contributions have dropped by one-third, college enrollment has plummeted, attendance at their annual conference has declined, and at least three factions have splintered from the church. Many former members attribute the declines to current president L. Craig Martindale and the board of trustees.

Growth, Then Trouble

Starting in 1967 with a handful of people and the family farm, Victor Paul Wierwille founded and parlayed his new church into a multimillion-dollar empire, operating two colleges, two ranches, and a publishing concern. In recent years the group has shown a net profit of at least 26 million dollars. The Way’s phenomenal growth is traced, in part, to the Power for Abundant Living (PFAL) discipleship course developed by Wierwille. Over 100,000 people in all 50 states and 40 foreign countries have taken PFAL.

However, since the installation of Martindale as president and the subsequent death of Wierwille, The Way International has experienced setbacks. In 1985 the Internal Revenue Service revoked their tax-exempt status for engaging in political campaigns (it was regained this past October). The following year questions about the leadership began to surface when Chris Geer, ordained by The Way, presented a paper to The Way leadership and to The Way Corps (the missionary arm of the movement). The paper, called The Passing of the Patriarch, effectively established Geer’s spiritual authority, which, in turn, challenged Martindale’s leadership.

Damage Control

Because of this and other similar actions, resentment of the leadership quickly escalated to such an extent that Martindale held a special clergy meeting to discuss Geer’s criticisms. He confessed in a newsletter that “Situations needing to be addressed in the ministry have deteriorated.”

By January 1987, letters were circulating in The Way Corps calling for either the restoration or dismissal of the board, which includes Martindale. Fragmentation became inevitable the next month when four highly respected leaders of The Way—John Lynn, Ralph Dubofsky, Thomas Reahard, and Robert Belt—coauthored a letter to Martindale challenging the legitimacy of the current leadership.

As with a previous paper, everyone who signed the 37-page letter was dismissed or put under pressure to resign. In an attempt to control damages, Martindale met with Geer, won his political support, and had him renounce the four dissenters.

After being dismissed, Lynn openly accused the leadership of endorsing adultery and forced tithing, and negating the divinity of Christ. This marked the first open criticism of leadership on the specific issue of adultery.

Breaking Rank

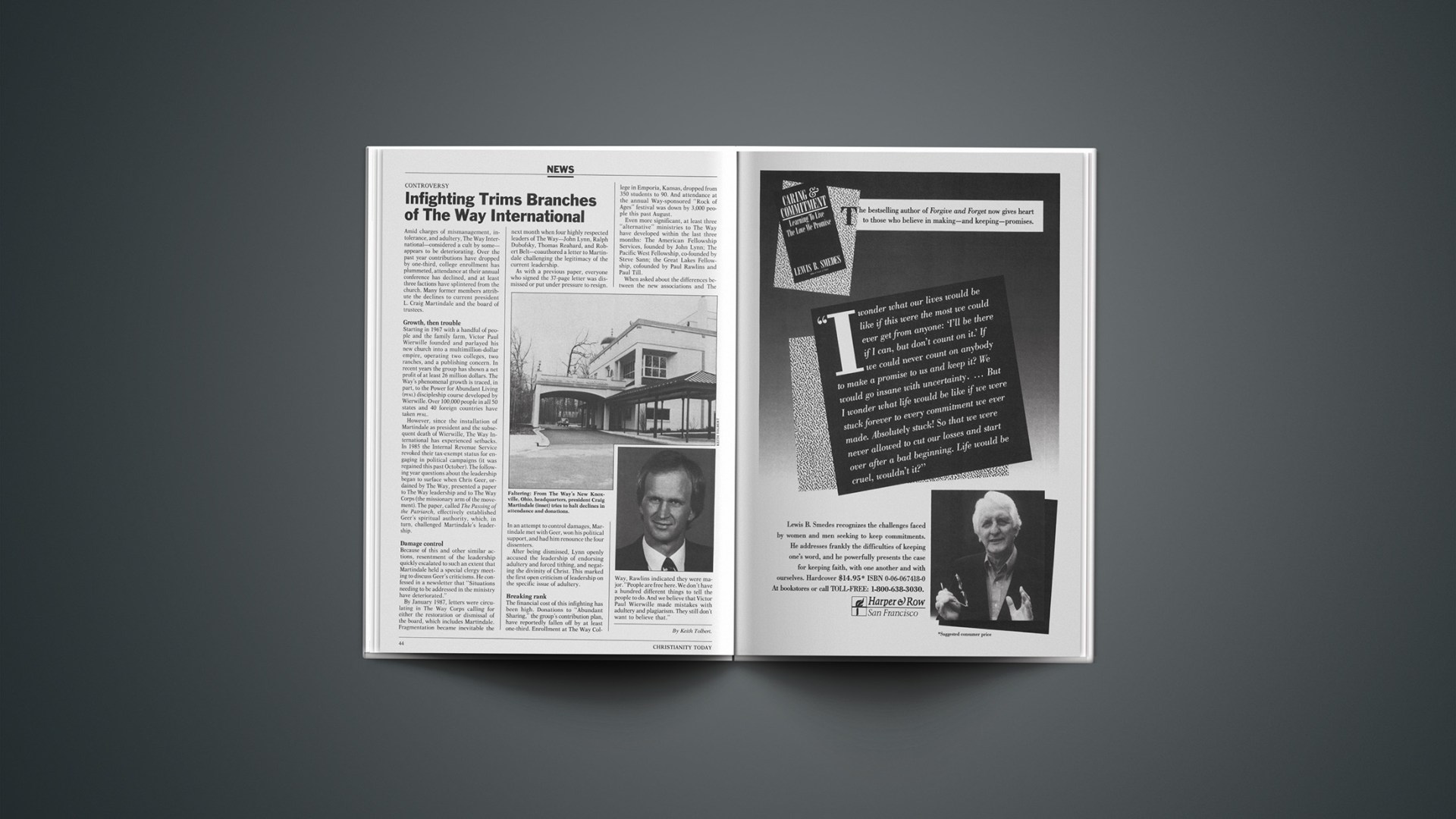

The financial cost of this infighting has been high. Donations to “Abundant Sharing,” the group’s contribution plan, have reportedly fallen off by at least one-third. Enrollment at The Way College in Emporia, Kansas, dropped from 350 students to 90. And attendance at the annual Way-sponsored “Rock of Ages” festival was down by 3,000 people this past August.

Even more significant, at least three “alternative” ministries to The Way have developed within the last three months: The American Fellowship Services, founded by John Lynn; The Pacific West Fellowship, co-founded by Steve Sann; the Great Lakes Fellowship, cofounded by Paul Rawlins and Paul Till.

When asked about the differences between the new associations and The Way, Rawlins indicated they were major. “People are free here. We don’t have a hundred different things to tell the people to do. And we believe that Victor Paul Wierwille made mistakes with adultery and plagiarism. They still don’t want to believe that.”

By Keith Tolbert.