A year from now, readers may already have reached their limit in what promises to be a nonstop year-long barrage of chatter in anticipation of the new millennium. We would like to get in a word before you are thoroughly jaded.

It is not given to humans to know the future, but as long we are mindful of our limited vision we can construct probable scenarios. Here is a forecast for the twenty-first century: More than any previous era, the century to come will demonstrate the awesome extent to which God has granted to his creatures the power to create, to manipulate, and to destroy.

We are made in God’s image and likeness; we are, as J. R. R. Tolkien said, “sub-creators.” That theme has long been a staple of Christian anthropology—so, we say, J. S. Bach was imitating his Maker when he composed great cantatas, and so is every artist and architect and storyteller, every human maker, whether or not he acknowledges the source of his gift.

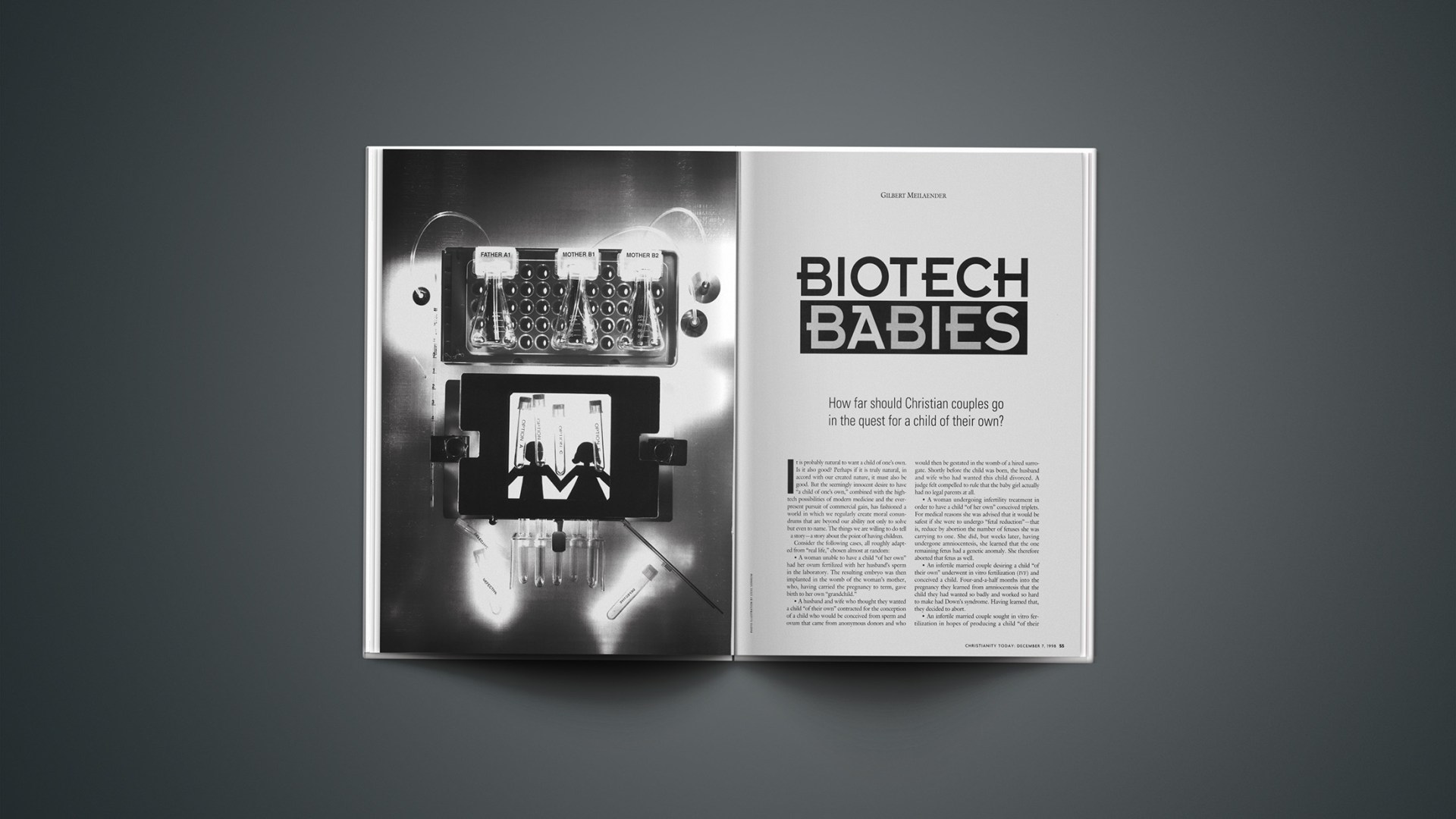

But in the century to come, “sub-creator” will take on a new intensity. We are likely to see, within the next hundred years, the cloning of human beings. We are likely to see artificial intelligences that are not merely—merely!—supremely good at specialized tasks such as chess or blackjack but rather are able to interact intelligently with the blooming, buzzing, category-crossing Real World. We are certain to see widespread and diverse approaches to genetic enhancement, not only of potatoes, but also of people; human enhancement via neural implants is also likely. We are certain to see reproduction divorced from the human setting in which it has always taken place; many children, to be sure, will enter this world the old-fashioned way, but many others will not (see “Biotech Babies,” p. 54).

None of this should startle anyone who has read a newspaper in the last year. All of these prospects and many more have been duly reported and analyzed. Occasionally a group of academics will gather to discuss the ethics of cloning or the new reproductive technologies. Some good books by Christian scholars have addressed these questions and related ones. But what has not gotten started yet is a sustained conversation within the church about the Brave New World we are about to enter: a world rich with new possibilities for good and evil.

In the world of the twenty-first century, age-old assumptions about what it means to be human will be proclaimed obsolete. On the one hand, humans will be able to exercise a control over their own making that encroaches on what have always been regarded as divine prerogatives. (Not a few scientists are saying, Listen, we are as gods; we’d better get on with it.) On the other hand, so we will be told, the development of ever more intelligent machines will give the lie to notions of human specialness. After all, as the MIT artificial-intelligence guru Marvin Minsky likes to say, we are just machines made out of meat.

How will Christians respond to such developments? One scenario calls for a wholesale rejection of science and all its works. This is a favorite of science-fiction writers such as the novelist William Gibson, who often gives Christians distinctly unflattering bit parts as Luddite terrorist fundamentalists. That would surely be a tragically mistaken response. We need more Christians on the frontlines of research—like Francis Collins, who directs the Human Genome Project—and we need thoughtful, informed critiques, not apocalyptic rants.

Another scenario, one that is starting to be played out in some quarters, is blandly accommodationist, refusing to recognize the extent to which the vast and far-flung networks of science and the biotech industry are already moving willy-nilly into that Brave New World. Sometimes reality is apocalyptic.

Neither of these responses will do. To begin with, we must affirm that, disturbing as they are, these prospects do not undercut our faith. Cloning, artificial intelligence, genetic enhancement: all these are evidence of our nature as subcreators. They suggest that we have not previously realized how deep in us the image of God goes.

And, yes, all these prospects reveal our God-given freedom, the implications of which theologians and artists need to wrestle with more than ever before. The God who gave us the freedom to create cities and cathedrals has not prevented us from enslaving other human beings, raping and murdering, annihilating our fellow subcreators with the ruthless efficiency of the gas chambers or with the intimacy of a Hutu mob beating their Tutsi neighbors and former friends to death. God has also given us the freedom to sit in the kingdom of our living room with a second helping of fat-free ice cream and the tv droning on while the world about us comes apart. Yet we may not opt out of the responsibilities that creative power brings.

Will God permit human creativity to bring forth the Brave New World that seems to be taking shape? Will he see a second Tower of Babel rising and once again sow confusion among the arrogant builders? We don’t know. But until Christ returns, we must use our powers as he has called us to. We are in part responsible for the way that world will look. We need to begin preparing for it now—not with the desperate tactics of survivalists but with the equanimity modeled by Jesus, wise as serpents, gentle as doves.

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.