[This article is also available in Dutch.]

Imagine yourself as Indiana Jones, traversing the narrow, nearly mile-long Siq gorge, with mountain cliffs towering on either side. Turning a corner then reveals the vast expanse of the ancient city of Petra and its majestic Treasury, the first-century rock-carved tomb of an ancient Nabatean king. You pass by the 121-foot-tall structure and its statues of Roman and Egyptian gods, making your way up a steep 800-step ascent to the equally impressive Monastery.

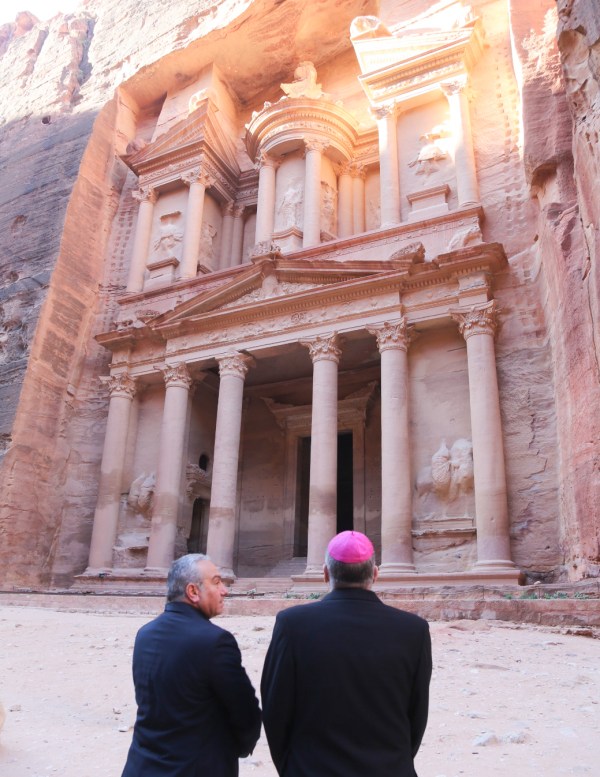

But before reaching Petra’s largest monument, you turn off the path into a different sort of ruin, mosaics lining the floor around half-sized recycled columns as incense wafts through the air. But unlike in the Harrison Ford movie, you do not meet an 11th-century knight preserved by the Holy Grail. Instead, the Greek Orthodox metropolitan of Jordan passes you a cup of Holy Communion.

In January, he offered the first Christian prayers in Petra in 1,400 years.

Other generations of film aficionados may prefer The Mummy Returns, Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, or even Mortal Kombat: Annihilation. While onsite Hollywood productions provide revenue for Jordan, this is dwarfed by the $5.3 billion the country earns from its tourism industry. In 2022, Petra received 900,000 visitors, nearly one-quarter of the national total.

But now, the Hashemite kingdom is adding a religious component.

“It is a great blessing to be in this holy place in Petra,” said Archbishop Christoforus, before proceeding to offer the bread and wine. “We are not thinking of what surrounds us in stone, but of the saints and spiritual identity in its heritage, history, and civilization—and our great and blessed [Jordanian] homeland.”

In 2021, Jordan launched a five-year national tourism strategy with an emphasis on religious sites, including the Vatican-endorsed pilgrimage locations of Jesus’ baptism at Bethany-beyond-the-Jordan; Mount Nebo, from which Moses viewed the Promised Land; and Mukawir, home to a Herodian palace where John the Baptist may have been beheaded at the biblical Machaerus. Approximately 85 percent of tourists come for cultural and heritage purposes, and one-quarter of baptism site visitors travel from the United States.

With such tourists likely to visit Petra already, Jordan would like to extend their stay.

“Unfortunately, Petra is known mostly for its Treasury and Siq,” said Fares al-Braizat, chief of the Board of Commissioners of the Petra Regional Authority. “There is plenty more it can offer, and the churches are an additional discovery.”

Ten have been discovered so far, with excavations ongoing. But the fifth-century Byzantine cathedral was only discovered in 1990 and fully unearthed eight years later. Restoration has proceeded sufficiently not only to inspire Braizat to add Petra to Jordan’s list of Christian historical sites but also to revive the ancient city’s religious heritage. It only adds to the nation’s reputation as an open-air museum, he said.

Jordan’s evangelical community is appreciative.

“How can you have a historic church site and not bless it with prayer?” said David Rihani, president of the Jordanian Assemblies of God. “Petra shows that the government cares about the history of Christianity in this land.”

The biblical history is even longer. Petra may have been inhabited as early as 7000 B.C. and became the capital of the Nabatean Kingdom around the fourth century B.C. The Jewish historian Josephus and the Septuagint translators connected the Arab tribe to Ishmael’s firstborn son Nebaioth, and some identify Petra as the biblical Kadesh where Moses struck the rock that gushed water in Numbers 20.

The Iron Age Edomites then refused the Hebrews passage along the King’s Highway—located in Jordan—and Aaron thereafter died and was buried at Mount Hor. Local tradition, Josephus, and the Christian historian Eusebius place this in Petra, where a mountaintop shrine is said to cover his tomb.

Herod the Great, supported by Cleopatra, plundered Nabataea in 32 B.C., but his son Herod Antipas married the daughter of the Nabatean king Aretas IV, whom he divorced in A.D. 27 in favor of Herodias, his brother’s wife, causing the controversy with John the Baptist.

Petra’s initial Christian history is quite contested. After conversion, Paul says in Galatians 1 that he immediately went to “Arabia,” which scholars identify with the Nabatean Kingdom, which included Syria. Many believe this three-year sojourn was a time of contemplation. But noting that Paul’s Damascus Road experience was accompanied by his call to apostleship, Martin Hengel argues that this was actually Paul’s first missionary journey.

Jewish Targums relate that Abraham’s wife Hagar settled in the area, and Paul speaks of her in Galatians 4. A Jewish community is known to have existed in Hegra, the second most important city of the Nabatean Kingdom, located not far from Petra. Isaiah 60 mentions the “rams of Nebaioth” offered on Jerusalem’s altar, and Hengel speculates Paul may have been motivated by this vision of the messianic kingdom.

Such explanation provides context to the 2 Corinthians 11 account of Paul’s escape from Damascus, lowered in a basket from the city wall. Acts 9 attributes the trouble to Jewish leaders, but Paul specifically names the governor of Aretas, the only mention of a contemporary ruler in his epistles. It would not be hard to imagine that the apostle’s preaching disturbed his Hellenistic brethren and that the local leader stepped in to calm the scene.

But there is no archaeological evidence that Paul visited Petra, or that the apostle otherwise features in the conversion of the Nabatean people, said Pearce Paul Creasman, executive director of the American Center of Research (ACOR), recognized as a “genius” by National Geographic. Based in Amman, ACOR was founded in 1968 and excavated the Byzantine Church in Petra in 1992. Over the next several years, three other ecclesial sites were unearthed, chronologically descending the mountain.

The late fourth-century Ridge Church is understood to be the oldest, with the Blue Church—named after its colored Egyptian granite construction—likely slightly preceding the originally named “Petra Church,” to which the fourth structure, a baptistry, was later attached. All are easily accessible to tourists today.

The church father Athanasius mentioned a Bishop Asterius of Petra, who denounced Arianism as a heresy and was sent into exile before being restored to his position by Emperor Julian in A.D. 362. Archbishop Christoforus stated there were seven dioceses in Petra, jurisdictionally under the church of Jerusalem. And a set of about 140 papyruses discovered in the Byzantine Church in 1993 show a flourishing community as late as the sixth century. The Greek script depicts a type of proto-Arabic and describes how Emperor Justinian’s edicts were applied locally within only one year of issuance.

But current research, Creasman said, cannot determine how Christianity came to the city. Tombs marked the deification of Nabatean kings, while temples facilitated the worship of the local god Dushara and his three female cohorts al-Uzza, Allat, and Manat. Petra lost its independence to the Romans in A.D. 106, and an earthquake in 363 sealed a decline from its golden era as a regional caravan hub, displaced by Syria’s Palmyra and emerging sea routes.

Yet history is replete with examples of how new religious ideas took hold in trading cities, and Petra was then a lush green center in a regional desert that at one time attracted a population of over 20,000 people. All currently discovered Christian sites, however, date after the earthquake, as the new landscape afforded the opportunity to recast the city in its Christian identity.

Some scholars believe that Petra continued as majority pagan, and while some temples were repurposed—or at least marked with crosses—others maintained their original function. The famous Monastery, originally dedicated to King Obodas I, was transformed into a church at an unknown date, while the Treasury also features later Christian carvings.

“Views and beliefs change,” Creasman said, “even as populations stay the same.”

Petra thereafter fades from history, with little known about the region’s Islamic transformation. There is a 12th-century Crusader castle, and evidence of Muslim curiosity when the Egyptian Mameluke sultan visited a century later. Petra was not rediscovered by Western exploration until 1812, receiving UNESCO World Heritage Site designation in 1985. In 2007, it was voted one of the new seven wonders of the world.

But it is Petra’s status as an “icon of the Arabs” that gives it special significance to Jordanian Christians, said Chris Dawson, a British assistant professor of historical theology at Jordan Evangelical Theological Seminary (JETS). Author of Travel Through Jordan, which he calls a brief guide for Bible students, he has led tour groups to Christian sites for decades and describes 60 locations that shed light on the Scriptures.

“There is an idea that to be authentically Arab you have to be Muslim,” Dawson said. “Putting Petra on the map as an authentically Arab Christian city—however pluralistic it was—is an opportunity to show otherwise.”

But there are other locations as well. Pella is the Decapolis city to which Christians fled after the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70. Madaba, in addition to its famous mosaic map of the Holy Land, has a nearby church clearly depicting an Arab identity. And Jerash, one of the world’s best-preserved Greco-Roman cities, allows modern-day believers to imagine a civic life permeated by paganism.

With a previous temple to Zeus built by a surely unrelated “son of Zebedee,” Jerash hosted incense altars to gods, along with what archaeologists have identified as an oracle, an idol-making factory, and a meat market once stocked with the remains of sacrifices. Considering Paul’s teaching in 1 Corinthians 8, how might Christians have navigated their diet and otherwise culturally related to their surroundings?

“Go not so much for pilgrimage,” Dawson said, “but to put yourself in the shoes of the early believers. It helps us understand their pressures.”

But while Christianity faded from Petra and other Jordanian cities with the advent of Islam, there is an enduring link between them and the followers of Jesus today. Dawson cited how early Arab Christians took the third-century Roman persecuted Cosmas and Damian as patron saints and named churches after them throughout the region—including in later day Jerash. And the Arab Ghassanid tribe adopted same-era Sergius, a Syrian soldier decapitated for his faith.

Dawson’s colleague at JETS is a Ghassanid descendant.

Haidar Hallasa, a 76-year-old faculty member and pastor in the church of the Nazarene, has dedicated the latter half of his life to studying Arab Christian history. Author of Arabic titles translated Jordan’s Biblical Geography and Our Forgotten History, he said many modern Christians throughout the Levant descend from the ancient tribe—which originated in fourth-century Yemen.

His great-grandfather, a Bedouin Muslim, came to the Transjordan region in 1735, fleeing from his crimes in the Bethlehem area. Describing himself as an Egyptian Copt, he took a job as a shepherd, developing a reputation for honesty that eventually led to a marriage with the one-eyed daughter of a tribal leader.

Hallasa’s resulting subtribe, he said, boasts 10,000 people today.

But the Ghassanids were not the only Christian tribe with influence. During the early Islamic era, the first Umayyad caliph, ruling from Damascus, married a daughter of the Benu Kalb tribe and appointed her Christian relative as the ruling prince of Tiberias. Many members eventually converted to Islam and others fled to Constantinople, so Hallasa sometimes tells open-minded Muslims that their personal religious identity may stem not from faith but from poverty. While intermarriage is a sign of fluctuating good relations, Arab Christians were assessed sometimes exorbitant jizya taxes that designated them as second-class citizens.

In hope that greater knowledge of history might encourage some to ponder the gospel, Hallasa has chronicled an additional 52 tribes from the Arabian Peninsula with Christian origins. But his primary message is for social tolerance.

Though it has been challenging, he has won such acceptance in his native Karak, 75 miles south of Amman—a city once belonging to Moabites, Nabateans, and Christians but that is overwhelmingly Muslim today.

“Radical Islamists want to divide us,” said Hallasa. “I say the opposite: You were Christians, we stayed Christians, but we are all one people.”

Also a Ghassanid, Rihani believes that evangelicals have a special role to play in relating Jordan to global Christianity. Tourists not only bring economic benefit for a struggling economy but interaction with their faith. And those who come to the Holy Land and extend their stay in Jordan further promote an exchange of peace.

Christian prayers in Petra can only help.

Vaguely aware of this history before the announcement, Rihani said it highlights how Jordan had a role in spreading the Bible throughout the region. But mostly, Petra’s Christian prayer is a form of divine encouragement.

“God is telling us, I’ve been here before, and I will continue with you,” Rihani said. “We should not have stones without spirituality, as the message of the gospel is alive in Jordan.”