There have been many devoted female missionaries and Bible teachers in the history of the Chinese church. But the ordaining of woman pastors is still opposed or viewed with reservation in many Chinese churches, both within China and overseas. Surprisingly, however, the first female priest ordained in the global Anglican Communion was Chinese—Florence Li Tim-Oi (1907–1992).

Li Tim-Oi was born in May 1907 in Shek Pai Wan, Hong Kong, during an era of social upheaval and gender bias. She was one of five siblings. Her father, who served as principal of an English government school for over 30 years, had once been invited by Sun Yat-sen to join the revolution to overthrow the Qing Dynasty. Li’s father valued social reform and hoped one of his sons would become a pastor, but none showed interest. Li, however, developed a passion for the Christian faith and a desire to spread the gospel.

Li’s mother attended a girls’ school founded by Catholic nuns. Influenced by her parents, Li developed a strong sense of self-reliance and leadership from an early age. In 1931, she enrolled in Belilios Public School. During an Anglican church ordination ceremony for Hong Kong and Macau, the archdeacon asked if any of the girls were willing to commit to serving the Chinese church. Li immediately responded, “I am here, send me—but do I meet your requirements?”

After graduating from high school in January 1934, Li became the head of Li Shing School in Ap Lei Chau, Hong Kong. That same year, she visited Union Theological College in Guangzhou, where the dean, John Kunkle, encouraged her to pursue theological training. After discussions with the pastor of St. Paul’s Church (her mentor), she left her teaching job to study theology in Guangzhou.

The Sino-Japanese War erupted in 1937, and Guangzhou fell to Japanese occupation in 1938. In that year, Li graduated from seminary and began interning at All Saints’ Church in Kowloon, Hong Kong, serving as an assistant preacher for two years.

In 1940, Li was reassigned to Morrison Chapel of the Anglican Church in Macau, tasked with caring for refugees who had fled to Macau because of the Sino-Japanese War. After the outbreak of the Pacific War the following year and the subsequent fall of Hong Kong, an even greater number of refugees sought refuge in Macau. During this period, the region had a troubled social atmosphere characterized by rampant gambling, alcohol abuse, prostitution, and drug use. At that time, the Anglican Church in Macau did not have a resident priest.

On May 22, 1941, bishop Ronald Owen Hall of the Diocese of Hong Kong and Macau ordained Li as a deaconess. On Easter 1942, she began presiding over the Eucharist in Macau, spreading the gospel among the suffering population.

During the war, many men joined the military and foreign missionaries who were imprisoned in concentration camps. To ensure uninterrupted ministry, the Anglican Church in China decided to break with tradition and ordain a woman priest.

On January 25, 1944, Hall ordained Li as a priest in the Anglican Church of Zhaoqing, located in Guangdong, making her the world’s first female Anglican priest. Hall later developed close relationships with high-rank leaders of the Chinese Communist Party, such as Zhou Enlai. He praised Communism, earning him the nickname of the “Pink Bishop” (the color red symbolizes the Chinese Communist Party).

In 1946, the Archbishop of Canterbury challenged Hall’s decision to ordain Li, offering two options: either Hall would resign or Li would renounce her priesthood. Faced with this choice, Li sought God’s guidance and chose to give up her priestly title, desiring to fulfill God’s will. In her book, Raindrops of My Life: The Memoir of Florence Tim Oi Li, she expressed her willingness to serve the church humbly and without regret, embodying her life philosophy of submission and service without contention.

The next year, Li became the principal at St. Barnabas Anglican Church in Hepu of Guangxi Province, and the following year, she traveled to the United States to visit and learn from Christian schools in the country. Upon returning to China in 1949, she established a maternity home, a kindergarten, and a primary school in Hepu. Two years later, she began pursuing advanced studies in theology at Yenching University. From 1953 to 1954, she taught at Union Theological College in Guangzhou, serving as the dormitory supervisor for female students and assisting with the ministry at Savior’s Church.

During the Great Leap Forward in 1958, Li led theological students and clergy to Jianggao, engaging in various agricultural and animal husbandry activities.

In 1961, she underwent forced ideological education required by the Chinese Communist Party at the Sanyuanli Socialist College and embraced socialism.

This experience seems to have left some “red” traces in Li’s later thoughts and life. In August 1964, Li wrote a letter to the local government exposing Hall’s “imperialistic tendencies” and criticizing him as an “accomplice of imperialism and colonialism.” Ironically, among her accusations against him was the “exceptional ordination of a female priest.” She claimed to write as a counter-imperialist and a patriotic clergy member in line with the spirit of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement. Quite likely, this was a reluctant act of self-protection.

Despite the appearance of loyalty to the CCP, Li was not able to escape persecution. Shortly after the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, Li was assigned to work at the Forward Chemical Factory of the Guangzhou Christian Three-Self Association, handling tasks such as packaging medical syringes and waxing cupboard boxes. On August 25, 1966, Red Guards raided her home, injuring her and seizing valuable possessions. Her home was raided several more times after this incident.

After retiring from the chemical factory in July 1974 with a severe eye disease, Li had other health issues but persevered in physical exercise and recovered. In 1979, as China reformed and opened up, she began teaching English and re-entered church ministry.

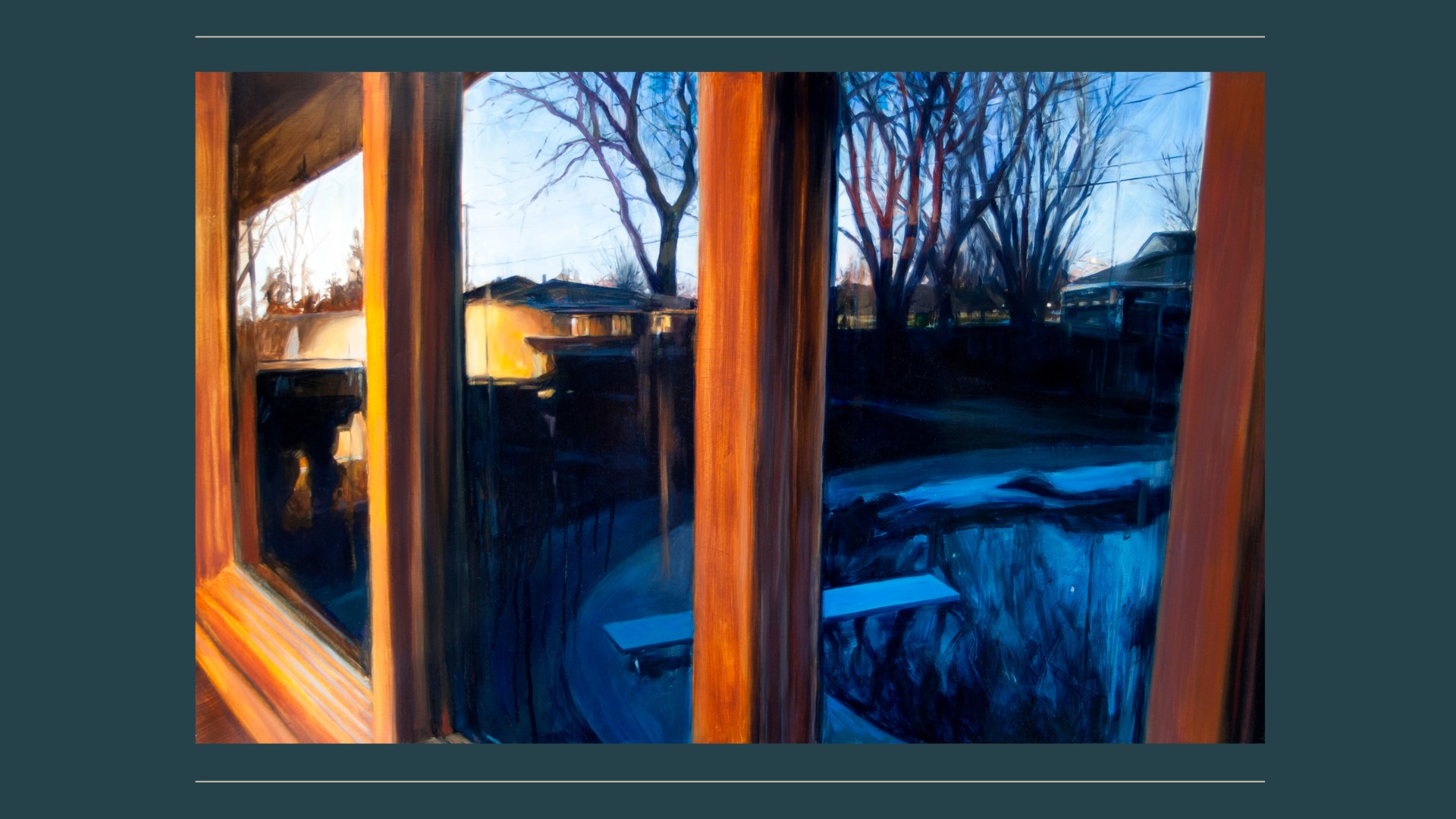

In November 1982, Li moved to Toronto, Canada, and served at All Saints Church under reverend Philip Feng’s pastoral care. In 1984 her status as a priest was fully recognized by the Canadian Anglican Church.

1987 was a significant year for Li. On May 9, Geoffrey B. Stephenson of St. John’s Anglican Church in Toronto led a thanksgiving gathering to celebrate her 80th birthday and established an associate church in her name. Additionally, The General Theological Seminary in New York awarded her an honorary doctor of divinity degree, which she accepted with her sister, Li Chi-ching, alongside her.

The following year, Li attended the Lambeth Conference of the Anglican Communion in England as an invited guest.

Li passed away in Toronto on February 26, 1992, at age 85. Anglican communities in the West regard her highly, and some regions have established commemorative days and special gatherings to honor her memory. The Li Tim-Oi Foundation, founded in 1994, aims to support missionary and pastoral work in the Global South.

Huang Yuan Ren is a Christian media editor currently residing in Shaanxi, China.

Translated into English by Ariel Bi