The guts of the house spill through its blown-out windows like entrails from a sacrificed animal. The resident of this house in Kfar Aza, Israel, died during the attacks that tore it to pieces on October 7, 2023. The debris of his life—books, board games, furniture, lamps, clothes, pillows—pour out onto the front yard where they are now being soaked by the rain.

I’m standing on the porch, making sure my recording equipment is covered and dry. A corrugated metal roof, ripped halfway off, hangs over the porch and waves in the wind. It lets out a high and lonesome sound like a musical saw or the moan of a ghost.

Most of the houses on the block look like this one—shattered and gutted. The mood in Kfar Aza is dystopian, as though the world ended and people were left to pick up the pieces. Only, the world did not end on October 7. The repercussions of that day are being carried out in Gaza as I stand there, and they echo on city streets, at college campuses, and in schuls and synagogues around the world.

Kfar Aza is a kibbutz that sits about three kilometers from the Gaza border. Like most kibbutzim, it was founded as a utopian, agrarian commune. These border communities were committed to peace, welcoming Gazans who had work permits to come serve the community. They were also the hardest hit by Hamas.

It feels both intimate and invasive to be here. I move to the living room. Like most of the homes here, it’s small. Through one doorway is an untidy bedroom where someone leapt out of bed when sirens went off at 6:30 in the morning. Turning around, I see a wall pockmarked with bullet holes and a ransacked room. Spots on floors and walls are bleached where blood was wiped away, and dark stains remain where it couldn’t be.

Of the 900 people who lived in Kfar Aza, about 1 in 10 was murdered or abducted. Many houses, like this one, have a black hole at the center where tires dragged from Gaza were piled and burned to drive a family from their safe room. The smoke turned walls and ceilings black and amber. I can still pick up a hint of ozone from an electrical fire, the acrid smell of burnt plastic, and something harsher that seems to seep from the black hole itself. I look up to see a woman also touring the kibbutz with me cover her mouth, turn pale, and move toward the door. I follow her.

In the days before coming here, I heard at least a dozen people say, “October 7 was the deadliest day for Jews since the Holocaust.” The phrase plays in a loop in my head as I walk through this space. The row of wrecked houses recalls the Warsaw Ghetto after the Nazis tore it apart and sent its residents to death camps. Earlier, we stood outside another house riddled with bullet holes that evoked thoughts of the Einsatzgruppen, Nazi killing squads that rounded up Jews on the Eastern front and shot them—men, women, and children—while they stood in mass graves they’d been forced to dig moments before. And then, of course, there’s the fires and the ash, black holes everywhere you look. The word holocaust has its origins in ancient Greek and refers to a sacrifice burnt whole.

The Nazis built factories for death in backwaters using the tools of industry and mass transportation to carry out their work with a methodical, almost clinical cruelty. Hamas did the opposite. Savagery was the point. They wanted it to be seen. In an audio file intercepted by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) from October 7, a Hamas terrorist called his parents from a kibbutz just down the road from Kfar Aza. “Look how many I killed with my own hands!” he says. “Your son killed Jews!” A little later he adds, “Mom, your son is a hero.”

“I wish I was with you,” his mother said.

What story is being told through that phone call? What story has been told, again and again, year over year, to enable a son to call his parents with effusive joy over the slaughter of innocent people? To answer that question is to discover the ideology of Hamas.

Ideology is a story that offers a key to history. It frames a present crisis such that it points to an inevitable future. It also creates the overwhelming sense that the future is certain, and that its followers are agents of the progress of history. That sense of inevitability has a powerful—and terrible—effect on its subjects; they become capable of immeasurable cruelty.

Alexi J. Rosenfeld / Getty

Alexi J. Rosenfeld / GettyNazi ideology proposed that the German people were destined for global rule but were being subverted by the Jews. Within this story, the extermination of Jews wasn’t murder; it was speeding up a necessary historical process. Telling that story again and again through propaganda let Nazi officials and functionaries imagine themselves as good people who weren’t merely doing their jobs but were doing bold, daring work ushering in a utopian future.

Ideology can take on a thousand forms and justify all manners of evil. Stalinist ideology advanced mass murder in Russia. The cult ideology of NXIVM led to sex trafficking. Maoist ideology resulted in the Chinese government’s oppression of Uyghurs. When history is believed to be at stake, people can justify almost anything.

Hamas is driven by its own antisemitic ideology, expressed in the utopian slogan “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.” By free, it does not mean “a free and democratic state for all its citizens.” It means Judenrein—a Nazi term meaning “cleansed of Jews” or “free of Jews” that some have invoked toward Hamas. This is their key to history—the one problem that, if solved, would move history toward its utopian destiny.

Knowing this makes sense of some of the more incomprehensible scenes from October 7. For instance, while the barbarism of the attacks shocked the world’s conscience, it was greeted on many Palestinian streets with joy. Many ordinary citizens—not militants—joined in the desecration of corpses in Gaza.

Then there’s the phone call and the mother’s response. Ideology tells a story that dehumanizes all Israelis, including the Muslim and Christian populations, and sees every act of violence as a necessary step in a utopian revolution. It’s why Hamas fires rockets indiscriminately, why they butcher children and women, why mass rape and sexual mutilation were part of the plan for that day. Ideology makes all such violence redemptive violence, an orgy of death advancing the progress of history.

Some might interject that there are parallels to Hamas’s ideology among Israelis, particularly in the right-wing settler movement. There’s some truth to that. The most radical elements of the settler movement envision the reclamation of all the historic land of Israel, which would require at least the subjugation, if not the wholesale displacement, of Arab residents. But it’s a fantasy to act as though there is symmetry between this movement, which even under the right-wing government remains a small faction, and Hamas, the governing authority in Gaza before October 7. The vast majority of Israelis celebrate the liberal nature of the state and will be the first to brag of the equal rights and privileges of their Arab citizens.

It is the ideological nature of Hamas’s vision that makes this conflict so intractable. When you’ve defined a Jewish state as the primary obstacle to utopia, when you’ve enshrined violence as an almost sacramental means of pursuing that utopian future, and when you’ve spent decades telling that story to your children and their children, any talk of peacemaking will remain irrational. That isn’t to say peace is impossible, but it is to suggest that until you do the work of articulating a better story, one in which violence no longer serves as a means of redemption, this cycle will continue.

There are important downstream implications to this fact, many of which have been exposed during the war in Gaza. Hamas exercised a kind of totalitarian control. For the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) and Doctors Without Borders to accomplish their humanitarian mission there, they had to be aware of Hamas. Thus they would have had to keep quiet, deflect, or openly lie about the presence of Hamas at hospitals, caches of weapons at schools, and the group’s ubiquitous tunnel network.

There were only two options: Cooperate with Hamas, which meant ignoring, enabling, or turning a blind eye to terror activity; or abandon their mission and abandoning those they were committed to serving at the same time.

Here again ideology played a role—though a different ideology than that of Hamas. In this case, it was anticolonial ideology, imported from places like Algeria, South Africa, and India, where European colonialism impoverished indigenous people and created a two-tiered society. Palestinian nationalists embraced the language of this ideology, and with the boosting of the Soviet Union in the 1970s and ’80s, it took hold in the global Left and the academy, reframing the Israel-Palestine conflict as a clash between European colonizers (Jews) and the indigenous people of the land (Palestinians).

As with many ideological histories, this one does not withstand scrutiny. Even if someone rejects the Bible as a historical document, the archeological record affirms Jewish presence in the land as early as the ninth century B.C. With modern Zionism, the parallels with European colonialism are almost nonexistent, since most Jews who settled in British Mandatory Palestine (and the Ottoman Empire before that) came fleeing instability, violence, and mass slaughter, often purchasing their land at a premium. A majority of Jews who came after the establishment of the State of Israel came as refugees, particularly after neighboring Arab states seized their Jewish residents’ property and kicked them out.

The violence between Jews and Arabs that began in 1947 and 1948 was not a conflict between a foreign empire and an indigenous population but between two groups with valid, historical claims to the land. The displacement and deaths of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians resulting from that conflict is a tragedy, and their continued statelessness is a scandal. But neither people’s struggles are the result of colonialism.

Similarly, the distinctions that make Jews part of the problem of “white supremacy” forget that white supremacists have chanted things like “Jews will not replace us,” and that more than 60 percent of Israeli Jews are Mizrahi—from the Middle East and North Africa—meaning they are not “white” by any definition of the term.

Nonetheless, this ideology took hold in the academy and many institutions populated by its graduates. Thus in marches against the war, one might see the Hamas flag waving near signs that read “Queers for Palestine” or “Abortion rights are Palestinian rights.” The common thread is not liberty or human rights, since Hamas cares little for these values. And it certainly isn’t the theocratic vision of Hamas, which would contradict all the values of the academy.

In reality, they share one common thread they reach from different directions: Hamas uses an Islamist and nationalist ideology to demonize Jews, and the academic Left uses anticolonial ideology to do the same. And both embrace redemptive violence against Jewish bodies as a means to restore justice to the world.

It’s the morning after my trip to Kfar Aza, and the Old City of Jerusalem is deadly quiet. At almost 10 a.m., these streets would normally be crowded. Merchants would cluster in entryways playing backgammon and dominoes on rickety tables or upturned five-gallon buckets. The smell of fresh fruit would waft out of shops selling juices and smoothies, mixing with the exhaust of scooters and motorbikes that weave through the crowds. Everywhere, you’d see clusters of slack-jawed tourists wearing matching lanyards, staring at street signs and half listening to tour guides shepherding them toward the Western Wall or the Via Dolorosa. Today, though, I can hear my own steps echoing on the stone walls.

Most of the shops are closed, but the few remaining merchants all remember me from yesterday. Out-of-towners are rare right now.

“Kentucky!” one shouts as I approach. “Hey KFC, Colonel Sanders. I have your herbs and spices.” His companion in the shop doorway laughs. I smile and wave, ignoring his pleas to stop and look at the scarves and trinkets by the door.

“Bring something home to your wife or your girlfriend—or both!” says another, a couple of doors down. That gets a big laugh from his neighbor.

“Tomorrow,” I say, hurrying past. “I’ll shop tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow?” he says. “Tomorrow we die, Kentucky. There’s a war going on; come, look.”

I feel bad, knowing that he’ll get no business today. Just before I turn the corner, I hear one of them yell, “See you tomorrow, Colonel Sanders!” to a roar of laughter.

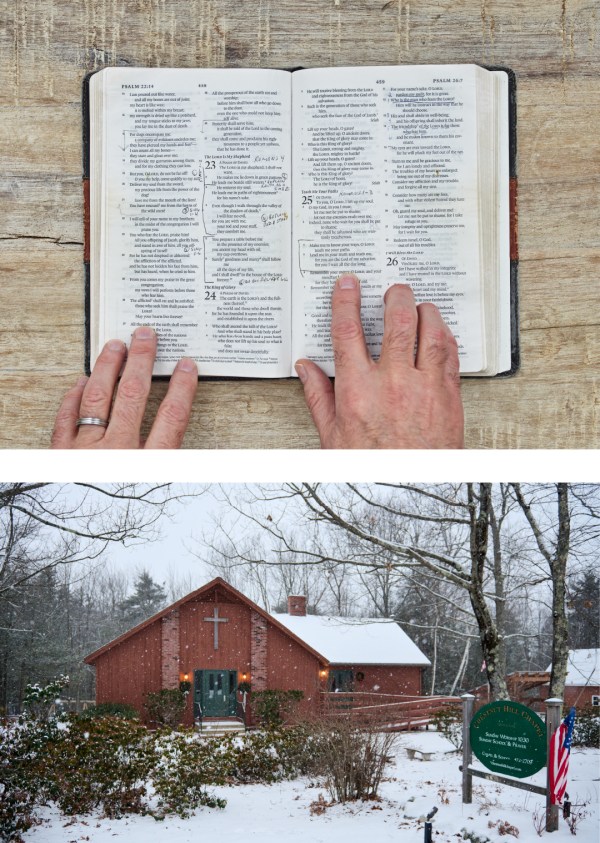

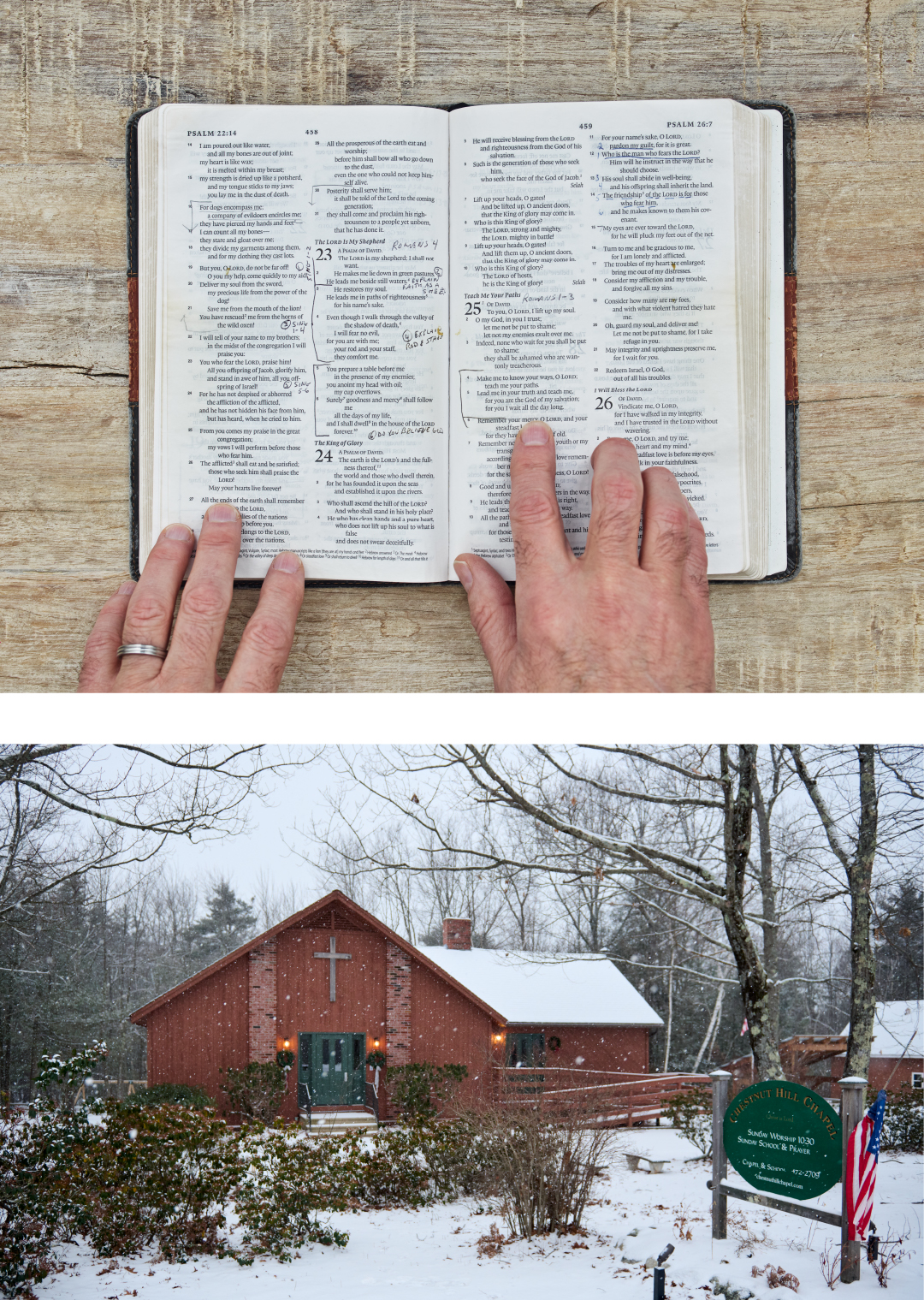

Michael Winters for Christianity Today

Michael Winters for Christianity TodayAfter that, my walk through the Old City is silent. I pass alleys that smell of sewage, open windows blaring news bulletins, and at least a half dozen cats sprawling on limestone steps before I come to a narrow door and a bright, open plaza. I turn to the right to face the façade of an ancient church. Behind me, looming over the church, is the minaret of the Ayyubid mosque, built on the site where Caliph Omar prayed after he conquered Jerusalem in 637.

The church itself is unassuming. Many who visit find it disappointing, especially if they’ve encountered the beauty of Chartres Cathedral in France, St Paul’s in London, or St. Patrick’s in New York City. What they see when they arrive here is drab and disjointed, but I love it.

And I love it, in part, for that very reason. This is no ordinary church. It’s been knocked down, burned down, and rebuilt over and over. It is a patchwork of architectural styles as other buildings have attached themselves to its sides.

The space itself was sacred long before the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was built. It is traditionally recognized as the site of the Crucifixion and Resurrection.

Many evangelicals come to Jerusalem and visit the Garden Tomb not far away. It’s picturesque and meditative, a sort of nondenominational prayer garden that is exactly what one might hope for when searching for a place to reflect. But the archeological record supports the Church of the Holy Sepulcher’s claim of authenticity. Its tombs date to the right era; it would have been outside the city gates at the right time; and, most importantly, it was recognized as the correct location by both Romans (who sought to desecrate it with a shrine to Jupiter) and Christians (who recognized it as a sacred space) up until the building of the first church on its site in the fourth century.

No matter your tradition, it can be a disorienting place. The building has a heavy gloom. Typically, throngs of worshipers press through its narrow passageways, praying, weeping, grinning for selfies, and hoping for a little blessing from breathing the air where Jesus rose from the dead. I imagine it is where we might find Jesus today—not in a quiet park but in a throng of chaotic, needy people.

Today, it is almost entirely empty. A monk steps lightly across the stone floor. An American dressed like Jesus, who came years ago to live in simplicity and speak with pilgrims, heads toward a chapel. The only other sound comes from a construction crew.

Inside the doorway is the Stone of Unction, traditionally revered as the place where Jesus’ body was prepared for burial. Usually, a small crowd kneels to rub rosaries against the stone or kiss it.

I stand there for a long moment, imagining a handful of disciples carrying Jesus’ limp body from the cross to this stone. Isaac Watts’s words pass through my mind:

See from his head, his hands, his feet,

Sorrow and love pour mingled down.

Today especially, the sorrow feels tangible.

For centuries, Christians were the primary proponents of antisemitic hate. We blamed Jews for all manner of social ills, including the Plague, and spun conspiracy theories involving the sacrifice of children.

Christians blamed Jews for the murder of Jesus, since Jewish religious authorities arranged his arrest and demanded his execution. This notion of Jews as “God-killers” became the motivation behind all manner of disgusting and violent actions. It’s a lousy claim to make against anyone. Jesus himself exonerated those who participated in his arrest and condemnation. “No one can take my life from me,” he said. “I sacrifice it voluntarily. For I have the authority to lay it down when I want to and also to take it up again” (John 10:18, NLT).

Today, many in the West like to think of themselves as having left these tropes behind. But old ideas die hard, and antisemitism is a very old idea. After October 7, people have called for a new “intifada revolution” as the “one solution” to the Israel-Palestine conflict. This language invokes both the Palestinian Intifadas (periods of deadly terroristic violence in the 1980s, ’90s, and 2000s) and the Nazi party’s Final Solution. Even less subtle are mobs who have chanted, “Gas the Jews” and carried out violence against Jewish-owned businesses outside of Israel.

Antisemitism can manifest in subversive ways. As Christmas approached last year, advocates for Palestinians in Gaza began to circulate an image from Evangelical Lutheran Christmas Church in Bethlehem. The church’s usual crèche wasn’t on display this year; instead, the baby Jesus was wrapped in a keffiyeh and lying in rubble that looked like the aftermath of a bombing. The image went viral, and a number of global news agencies published stories about it.

“We don’t see this as a war against Hamas,” the church’s pastor, Munther Isaac, told The New York Times. “It’s a war against Palestinians. … This is what Christmas looks like now in Palestine, children being killed, houses destroyed and families displaced. We see the image of Jesus in every child that is killed in Gaza.”

In a similar gesture, a host of politicians, activists, and pundits celebrated Christmas by calling Jesus a Palestinian, likening the occupation of the West Bank to the Roman occupation of Judea or comparing the war in Gaza to Herod’s massacre of the innocents.

At a certain level, the desire to draw such parallels is perfectly understandable. The devastation in Gaza is hard to comprehend. The Hamas-run Health Ministry estimates more than 25,000 have died since the beginning of the war, and for many Palestinians, it is one more wound in almost a century of loss, grief, and displacement. It is legitimate to lament that suffering or to question the justice and proportionality of this war. We can unapologetically agree that Jesus weeps with those who weep in Gaza.

But these images and metaphors only serve to eclipse Jesus’ Jewishness. And the keffiyeh wrapped around the Christ child does this in a particularly troubling way.

A white headscarf with a gridlike woven pattern, the keffiyeh became a symbol of Palestinian nationalism during the Arab Revolt of 1936–1939. Yasser Arafat wore one in the ’60s as he sought to galvanize a nationalist movement among Palestinians.

Arafat, despite the hagiography of some, was described by former federal prosecutor Andrew McCarthy as a “thug” and “the father of modern terrorism.” Arafat invented new ways of doing evil (Rom. 1:30), developing tactics that targeted children, schools, shopping malls, and public buses. He monetized compassion for the Palestinians, enriching himself to the tune of billions of dollars. He rejected a two-state solution under the most favorable possible terms in 2000, leaving peace talks to start the Second Intifada.

But the keffiyeh’s enduring power as a symbol emerged because of photographs of someone else taken in 1970.

The subject of the photos was Leila Khaled, a Palestinian woman with the intense eyes and high cheekbones of a fashion model. She was photographed by Eddie Adams at a refugee camp in Lebanon holding a Kalashnikov rifle and wearing a keffiyeh—which was unusual, as it was typically a men’s scarf—in the style of a hijab. The ring on her finger was made from a bullet and a grenade pin.

By then, the world already knew her name. Months before, she’d taken part in the hijacking of a Tel Aviv–bound commercial flight, diverting it to Damascus and using its passengers to secure the release of Syrian and Egyptian prisoners of war. A few months after being photographed, she was part of another attack strikingly similar to 9/11. Four planes were targeted for hijacking, but Khaled and her partner failed. He was killed, a member of the crew was shot, and she was arrested and held until her fellow hijackers secured her release in a hostage exchange.

Today, she’s a sought-after speaker at human rights conferences. Her image is emblazoned on posters and murals throughout the Palestinian territories and throughout the Middle East. This is not because she’s moderated her positions and desires peace, but because she maintains the same revolutionary spirit that inspired her acts of terror in 1969 and 1970. At a speech at a conference in South Africa on October 14, 2023, one week after the Hamas massacre, she said, “It’s not enough to go to the streets. … The mainstream for people is to go to arms, always.”

Terrorism, in other words, is essential to the redemptive project for Khaled.

Such violence isn’t peripheral to the symbolic meaning of the keffiyeh; it is the symbolic meaning of the keffiyeh. For people like Khaled and Arafat, violence inflicted upon children, civilians, and the elderly is a necessary part of their revolutionary vision. It is ideological violence, justified by a utopian vision of Palestine made Judenrein from the river to the sea.

Of course, not everyone who wears a keffiyeh (or wraps the baby Jesus in one) does so with that intent. That is especially true, I’m sure, for those in the West who bought their keffiyehs on Amazon or at Urban Outfitters. But for Hamas and other militant groups that conspire to see the end of Israel—the kinds of places that make a hero of Arafat and Khaled because of their embrace of revolutionary violence—the symbolism is entirely clear.

We worship a God who became flesh and dwelt among us, who wept over the death of his friend Lazarus, and who sweat blood in anguish in the Garden of Gethsemane. To imagine him in the rubble in Gaza is to rightly understand the presence and solidarity of Christ with those who suffer—just as we might imagine him in the rubble of Kfar Aza.

But to wrap him in a keffiyeh goes beyond an effort in solidarity, embracing not just partisanship or nationalism but a symbol of violence that expressly sees the destruction of Jewish life as a key to history. It is the symbol of a movement that glorifies as martyrs those who strap bombs to their chest and blow up school buses. It is not a profound expression of identification or solidarity; it is an obscenity.

The people around Jesus hoped that he would take up arms against the Romans. He pointedly refused. On the one occasion that one of his disciples wielded the sword, Jesus told him to put it away (Matt. 26:52).

Likewise, calling Jesus a Palestinian is inaccurate and irresponsible. If it’s meant as a metaphor, it’s a clumsy one—as clumsy as saying, “Jesus is an American” or, “Jesus is a Samoan.” If it’s a historical claim, it’s an ignorant one. Jesus was a Jew from Judea, and the Romans established “Syria Palaestina” over a century after his resurrection, after the Bar Kokhba Revolt, as an insult to the Jews (the name referring to their ancient rivals, the Philistines).

Such sloppiness and disregard for fact is the natural fruit of ideological thinking: Its logic twists whatever comes near it the way a black hole bends light. In this case, making Jesus a Palestinian fits him into the narrative of decolonization, allowing one to believe that Jesus was born in Bethlehem while maintaining the fiction that Jews have no historical claim on the land.

The result is a dangerous moral distortion. It recruits Christians into the logic—embraced by the likes of Hamas and those who embrace the “settler-colonial” narrative—that blames Jews for the attacks of October 7. The presence of “colonizing” Jews, these groups insist, is oppressive to indigenous Palestinians and thus provokes the violence witnessed on October 7. Such logic leaves the war in Gaza with no justification, since it is merely one more expression of colonial power against indigenous people.

It’s also anti-Christian. If Jesus is anything but Jewish, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, he cannot be the Messiah. Making him otherwise only makes sense within the distorting logic of this ideology.

In the days after the war began, much was made of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s invocation to “remember what Amalek did to you,” a reference to biblical enemies of Israel. The Amalekites were particularly barbarous proto-terrorists, attacking the Israelites during the Exodus and targeting the weakest and most vulnerable among them (Deut. 25:17–18). They appear again in a war against King Saul and make a final appearance in the Book of Esther. The great enemy of that book, Haman, is an Agagite—a reference to Agag, king of the Amalekites, whom Saul spared against God’s command (1 Sam. 15:7–9).

In God and Politics in Esther, Jewish philosopher Yoram Hazony writes of the Amalekites,

We have no idea what gods ruled over the Amalekites. None are named, and for all we know, there may have been none at all. What we do know is that whatever gods may have belonged to Amalek, as a people they did not fear any moral boundaries established by them. Unlike even the most depraved of the idolaters of Canaan, they respected no limits on their desire to control all as they found fit.

The bottomless capacity for evil became for Jews a symbol of unconstrained antisemitic violence.

The warning to remember Amalek from Deuteronomy 25 is read every year at the beginning of the festival of Purim, which comes from the book of Esther and is a celebration of Jewish survival. Haman schemed to murder all the Jews in the Persian empire, and he nearly succeeded by seducing the king with an antisemitic conspiracy theory:

There is a certain people dispersed among the peoples in all the provinces of your kingdom who keep themselves separate. Their customs are different from those of all other people, and they do not obey the king’s laws; it is not in the king’s best interest to tolerate them. If it pleases the king, let a decree be issued to destroy them. (Esther 3:8–9)

The root of Haman’s hatred is the resistance of Mordecai, a Jew who refuses to bow to him as an idol. In this, we find another root of antisemitism: the demand for assimilation. Since God called Abraham, his tribe and heirs have been set apart from their neighbors by their beliefs and practices, and their refusal to assimilate has often made them objects of scorn. But as history shows time and again, what starts with Jews rarely ends with Jews. The Roman persecution of Jews was a predecessor to their persecution of Christians. The Nazis murdered millions of non-Jews—among them dissidents, Roma, Poles and Soviets, homosexuals, Christians who rejected Nazi ideology, and people with disabilities.

Michael Winters for Christianity Today

Michael Winters for Christianity TodayThe ideologies of decolonization and of Islamist terror organizations aim at wiping out Israel from the river to the sea, but their appetite for revolutionary violence is not likely to be that easily satisfied.

In contrast, Christians, especially evangelicals, should be the greatest champions of liberty and pluralism. Not only for the sake of our own freedom to worship as we choose, but for the sake of the gospel itself. The Good News shines brightest in a society where there is freedom to reject it, so that converts can truly shine their light before men. Antisemitism (in the form of Islamist ideology), anticolonialism, white supremacy, and even Christian nationalism are all forerunners to the erosion of freedoms that will hinder the gospel’s spread or distort its message.

Some heard Netanyahu’s invocation of Amalek as a call to vengeance against the citizens of Gaza, but few practicing Jews would have understood it that way, according to Rabbi Elchanan Poupko. (Indeed, Netanyahu’s own speech distinguished between Hamas and ordinary citizens.) Rather, like the invocation of Amalek at Purim, it’s a reminder that antisemitism arises anew in every generation and, by God’s providence, the Jewish people persevere.

The Aedicule, a shrine built around Jesus’ tomb, sits on the opposite end of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher from Golgotha. Light made hazy by candle smoke and incense streams in from windows in the dome above it.

It is emptier than usual this morning. Of course, “he is not here,” as the angel told Mary on Easter morning, but there are no pilgrims or worshipers today either.

It is this shrine that I think of most often when I think of Jerusalem—this place where the arc of history pivoted. It was a shocking reversal in fortune for Jesus’ disciples, and I have to believe it was a shock for the Devil himself. The gospels of Luke and John tell us he was behind Jesus’ betrayal (Luke 22:3; John 13:27), and Revelation 12 depicts him in pursuit of the Christ child from the moment of his conception, orchestrating all manner of violence against him. From the moment of Jesus’ arrest until his final breath on the cross, he unleashed every kind of pain and humiliation.

But in this limestone tomb, all that evil and destruction proved a failure of imagination. Satan could not predict that in pouring violence and hate into the body of Christ, he would actually liberate the body of Christ—the church—from captivity.

In this strange space, which for all its candles and embellishments doesn’t rise above its humble roots as a simple Jerusalem tomb, we find the only real “key to history.” It doesn’t provide us with an ideology. It offers no map to past or future, and it hardly answers all our questions. Instead, it places us in a story marked by both mystery and hope. It promises a future where violence will end, swords will be made into plowshares, and our sorrows with be gathered up like bottled tears, but it does not provide a simple road map for ushering that future into being. Rather, it invites patience and hope, and it promises the presence of Christ in the meantime, come what may.

As I kneel in the Aedicule, I think of the violence carried out on Christ’s body, a stone’s throw away at Golgotha. I think as well of Kfar Aza, where Hamas unleashed its death cult on Jewish bodies. I’m struck by the common threads between them.

Michael Winters for Christianity Today

Michael Winters for Christianity TodayBoth acts defy reason, since both invite a response from someone with radically disproportionate power at their disposal. But that is a revelation in itself; the violence and suffering were the point because the satanic hatred behind them wasn’t compelled by reason but by rage. Satan hates the Jewish people for the same reason he hates the church—they reveal something about the one he hates the most.

There are limits to the comparison, of course, and one such limit is the difference between Jesus, who said, “No one takes my life from me,” and the residents of Kfar Aza, who desired nothing so much as peace with their Gazan neighbors. While it is apt to suggest the murderous rage against them shares its origins with the hatred of Jesus, it is grotesque to suggest it is their duty to be slaughtered.

Here again, we turn to Esther. The central point of that book is not the justice that comes for Haman; it is Esther’s request. She risks her life to ask the king not to spare the Jews but to let them defend themselves. Esther is, in this sense, primarily a political text, describing not the attitude of an individual who must turn the other cheek when wronged by another but the responsibility of a tribe to defend its people from annihilation.

We can debate the details and the tactics by which Israel might do that. And we should. But it should be clear—when Israel is working to provide humanitarian corridors, food and medicine in aid, and advanced warning of air strikes, and when it explicitly says it is seeking to minimize civilian casualties—that there is no moral equivalence with Hamas, who says the opposite; targets civilians; and glories in the murder of women, children, and infants.

Only ideology can distort our vision and blind us to that moral asymmetry. If we are struggling to see it, we need to ask why.

Mike Cosper is the director of CT Media. He is the author most recently of Land of My Sojourn and the forthcoming The Church in Dark Times, a book exploring ideology in evangelicalism.