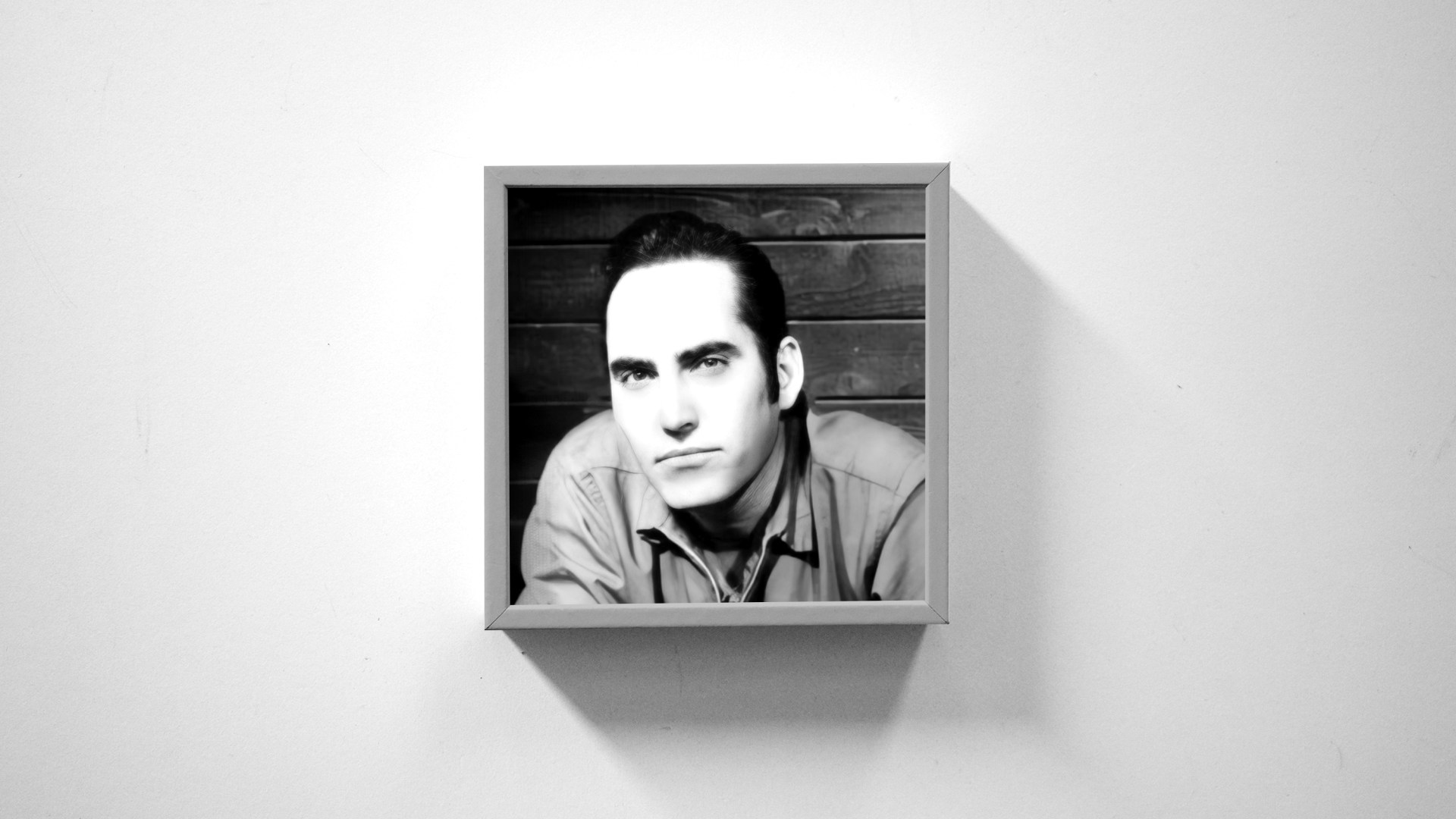

Michael Knott, whose music and influence helped cultivate the Christian alternative music scene of the 1990s and 2000s, died Tuesday at the age of 61. He is survived by his daughter, Stormie Fraser.

Knott was the founder of the label Blonde Vinyl and later collaborated with Brandon Ebel to launch the highly influential Tooth & Nail Records, known for bands like Underoath and MxPx.

His raw, innovative, and controversial music pushed against the norms of the industry and laid the groundwork for contemporary communities around Christian alt music.

“Knott helped prove that Christian music could be something legitimate, rather than running two to three years behind mainstream trends,” said Matt Crosslin, who runs the site Knottheads and has become an unofficial archivist of Knott’s work.

Even with his reputation for bucking standards, Knott’s sense of mission was earnest and singular.

“He wanted people to come to Jesus and be saved,” said Nathan Myrick, assistant professor of church music at Mercer University. “He seemed to offer a way of holding faith and raw authenticity in tension.”

Knott was born in Aurora, Illinois, and grew up with six sisters in what he described as a modern “von Trapp family.” They were constantly singing and immersed in music through their father, a folk singer, and their mother, a church organist.

When Knott was in second grade, his family moved to Southern California, where he began to take piano and guitar lessons at the YMCA. He started writing songs in his preteen years and would bury them in a folder in his backyard, convinced that nothing would ever come of his private creative life.

Despite his early shyness about his songwriting, Knott began playing with bands in high school and performing at local clubs and bars. After coming to faith, he started to feel like the music he was performing didn’t offer anything meaningful. Through contacts at Calvary Church in Costa Mesa, California, Knott connected with the Christian punk band the Lifesavors and joined. (They later rebranded the group as Lifesavers, then Lifesavers Underground or L.S. Underground)

Throughout his career, Knott performed with a number of bands and released music as a solo artist; his discography is sprawling and varied. He was heavily influenced by fellow California rock bands the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Jane’s Addiction but dedicated himself to driving the scene forward rather than creating copycat music for the Christian market.

Despite remaining a fixture and catalyst in the Christian alternative scene in the ’80s and ’90s, Knott struggled to make his way in the music industry and to sustain an upward trajectory. He launched the groundbreaking indie label Blonde Vinyl in 1990, but when its distributor went bankrupt in 1993, the label folded.

Knott’s band, Aunt Bettys, signed to Elektra Records (a label owned by Warner Music Group) in the mid-’90s, joining the ranks of Metallica, Tracy Chapman, and The Cure. After a short run with the label, Knott went his own way. There was speculation that Knott’s theatricality and eccentricities were worrisome for label executives.

In a 2003 article, HM Magazine described the many personas of Mike Knott: “a non-Christian,” “a liberal,” “a zealot like Peter,” “a Proverbial fool who speaks too often and too soon with too little thought first.”

For a time, he performed with his face painted white; in his early years with the Lifesavors he was kicked out of Calvary Church for dancing too wildly on stage (and reportedly for encouraging the audience to dance too). He also had a drinking problem, which he spoke and wrote honestly about.

Knott had a reputation for being uncompromising and persistent. Artists like Keith Green and Larry Norman developed similar reputations in the industry for bucking corporate norms and ignoring business advice.

Knott’s convictions about unfettered musical creativity and blunt truth-telling made him an industry black sheep; he was self-aware about the fact that his candidness sometimes chafed those around him. He joked that his nickname in the 1980s was “Captain Rebuko”: “If someone did anything wrong, I would rebuke ’em,” he told HM.

But Knott wasn’t interested in rebuking people for their struggles with worldly vices like drugs or promiscuity; he was concerned about hypocrisy, deception, and spiritual manipulation.

His conviction and condemnation were on full, unapologetic display in the L.S. Underground album The Grape Prophet. The album, which Knott described as a rock opera, tells the semi-autobiographical story of a faith community’s encounter with Bob Jones, Mike Bickle, and their group of Kansas City–based prophets that traveled the US during the ’80s and early ’90s.

Jones (the “Grape Prophet”) is depicted prophesying in songs like “The Grape Prophet Speaks.” According to Crosslin of the Knottheads site, the song “The English Interpreter of English” depicts Mike Bickle, the founder of IHOP, who has recently been accused of sexual abuse and other misconduct.

“Knott was calling out Mike Bickle in the early ’90s,” said Crosslin. “His music said, It’s okay to call this stuff out.”

Knott’s strident, painfully honest songwriting and musical experimentation was magnetic, even for Christian fans who sometimes wondered if they should be listening at all.

Writer Chad Thomas Johnston grew up listening to mainstream Christian pop and rock like Carman and Petra. The son of a Baptist minister in Missouri, he encountered Knott’s music through the Wheaton, Illinois–based Christian magazine True Tunes News.

“I was scared of his music when I first encountered it,” Johnston said in an interview with CT. “It was unflinchingly dark.”

Knott’s music addressed divorce, alcoholism, and drug use. He used profanity. “At the time, I couldn’t wrap my head around it. Christian artists were supposed to be singing Christian songs,” said Johnston.

When Knott helped found Tooth & Nail records in 1993, he attracted up-and-coming artists who were eager to join a label helmed by someone with a strong creative vision. In lending his credibility to Tooth & Nail, Knott laid the groundwork for the burgeoning Christian alternative scene of the 2000s, which saw Christian bands pull ahead and become the industry standard-bearers in metal and indie rock.

Those who have followed Knott’s work see a clear lineage from Knott to the spiritual and musical communities that formed around Christian alternative music through festivals like Cornerstone, and now Audiofeed and Furnace Fest.

“For many, the Christian alternative space is an extension of their church,” said Myrick, who is currently conducting ethnographic research on the Christian alternative music community. “People feel accepted, down to the core parts of who they are.”

Knott wasn’t only committed to the health of the alternative music scene—he was committed to the health of the singing church. He worried that the worship of the church didn’t reflect deep, complicated faith.

His 1994 album Alternative Worship: Prayers, Petitions and Praise aimed to offer something needed and unusual. The song “Never Forsaken” is a simple meditation on the Christian life that repeats the reassurance, Never left alone, never left alone.

“If you write a praise song and you’re honest, that will last,” Knott told Christian Music Magazine in 2001. “If you write a praise song just to write a praise song, it’s not going to work. If you write a song about a tree, and you’re honest, it’s going to work.”