The first piece of art I bring my art-history students to see in the museum is a glass cube, four feet by four feet. Square sheets of glass infused with metal make the sculpture simultaneously reflective and transparent. The cube has a polarizing effect on visitors, inciting responses that range from confusion to curiosity to contempt. I invite my students: “Turn your attention to the cube. Observe it for two full minutes.” That’s an eternity to look at something that seems to resist meaning.

By the time the exercise has finished, the students can’t wait to talk about the work, the way it refracts color and light. Our conversation is punctuated by laughter. The two-minute exercise underscores art historian Jennifer Roberts’ adage: “Just because you have looked at something doesn’t mean that you have seen it.”

Looking at art is confusing. Looking at contemporary art can be especially confusing. That remains true for me in my work as an art historian and curator. But I’m also assured: When I persevere in being with a piece, it imparts the “eyes to see and ears to hear” it.

In the meantime, the confusion caused by good art is valuable. It challenges what we think we know and how we know it. It resists our authority, not by exerting equal and opposite force but by striking us obliquely, throwing us off balance. Good work defamiliarizes us; it makes the world feel strange, new, and other—sometimes frighteningly so.

Earlier this year, I started curating a show for my university’s museum, featuring Larry Bell’s glass cube among other works. I sensed that these pieces had something important to teach me about Advent, even though they aren’t illustrative like the Merode Altarpiece or even made by Christian artists.

Anderson Collection at Stanford University, Gift of Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson, and Mary Patricia Anderson Pence 2014.1.090

Anderson Collection at Stanford University, Gift of Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson, and Mary Patricia Anderson Pence 2014.1.090Immured by two millennia of history, Advent often strikes me like that cube—complete, hermetically sealed, indifferent to my presence. But when I look into the glass, I find myself becoming remade in its reflection, startled by its alterity. It causes me to see myself, others, and the world differently. So too with Advent.

“Do not fear”: It’s one of the most repeated phrases in the accounts of the birth of Jesus. The angelic prologue is not followed by “I will explain everything to you” or “Everything will be okay.” Rather, it precedes unmitigated uncertainty. “Do not fear” was an invitation to see with the eyes of the Spirit rather than look with the logic of humanity. Zechariah, Mary, Joseph, and the shepherds were all invited to exchange their earthly understandings for the knowledge of eternity.

“Do not fear” has too often been translated into the American ideology of “happily ever after.” But in context, it was spoken by a terrifying, numinous being. It was a warning: Brace yourself to witness the eternal God in the form of a human baby.

Near the glass cube in the gallery hall loops a video made by the sculptor and dancer Nick Cave. His “sound suits” are composed of buttons, sequins, and fishing bobbers of all sizes, colors, and shapes, plus bundles of twigs and antique figurines. The result is a collection of surreal sculptural figures exploding with colors and textures, exuding an electric energy.

Nick Cave made his suits in response to the 1991 beating of Rodney King. “As a young Black male, you know, I was … feeling dismissed, discarded,” he reflected. “I was just trying to process that, and, you know, what does that mean. … I found myself one day in the park, and I looked down on the ground, and there was this twig. And, I don’t know, I just started collecting these twigs. … I sort of brought them back to the studio and started to build this object.” When he donned the suit, he noted its shimmering sounds and named it accordingly.

Discarded objects become joyful revelations. Despised, weak, and rejected materials become a strange conduit of hope, a profound illustration of 1 Corinthians 1:27. This is the kind of artwork that requires us to set aside our sensemaking—the suits are weird!—in order to see splendor.

Antonio Perez / Chicago Tribune / Getty

Antonio Perez / Chicago Tribune / GettyDuring Advent, God defies earthly power and reason; he uses a baby born into dirty straw to bring about redemption. We are reminded that we must surrender our ways of looking and knowing if we hope to see the kingdom of God (John 3:3).

Of course, it’s not just contemporary art that can help us understand Advent more clearly. Canonical works have something to teach us, too, if we can get past the layers of commentary and critique and see them anew.

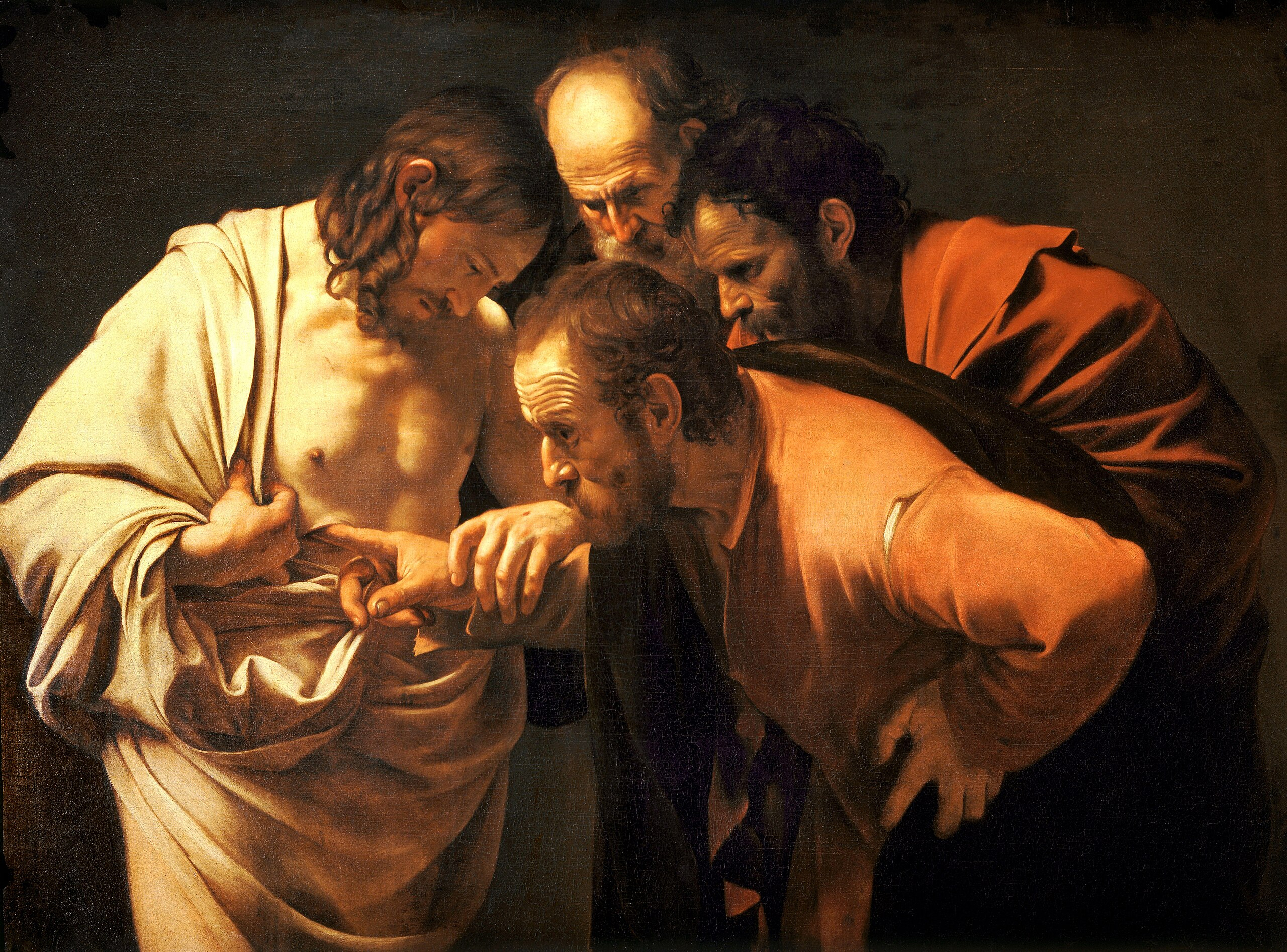

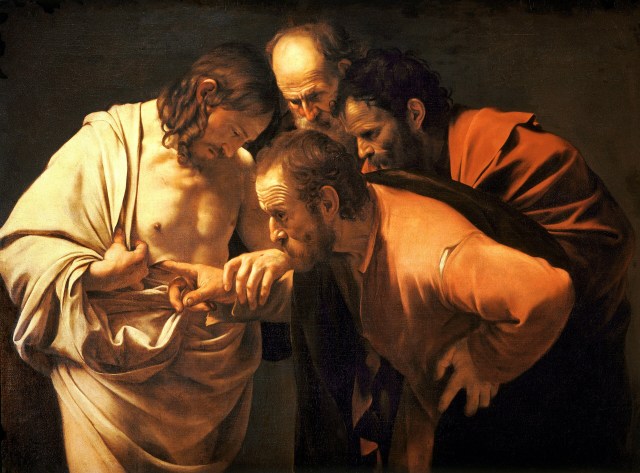

Caravaggio’s Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1602) isn’t included in my show. (The “secular” version is in a German gallery.) And once again, it’s not a Nativity scene. But it always makes me think about Advent too.

It’s hard now to comprehend how disruptive Caravaggio’s work was; Nicolas Poussin, one of the greatest painters of the 17th century, went so far as to say that the Italian painter “came into the world to destroy painting.” In the Incredulity, Caravaggio offers up a surrealist representation of the interaction between Christ and Thomas, taken from John 20:24–27. Christ guides Thomas’s hand into the wound in his side.

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsI find this the most moving, compelling metaphor for what happens when we begin to see an artwork—as we give our attention to it, we are drawn into its depth. Christ does not point the confused Thomas toward a scar that will satisfy his intellectual doubts. Instead, Thomas is being drawn into Christ’s side, toward a terrifying and gaping darkness.

In this version of the painting, Caravaggio renders the wound as neither past nor present but an eternal mystery—the lamb slain before the foundations of the earth, a God incarnated as a child.

My prayer is to see Advent as God does: to surrender to its wisdom and enter into its wonder.

Christian Gonzalez Ho is earning his PhD in art history at Stanford University and is the cofounder of Estuaries.