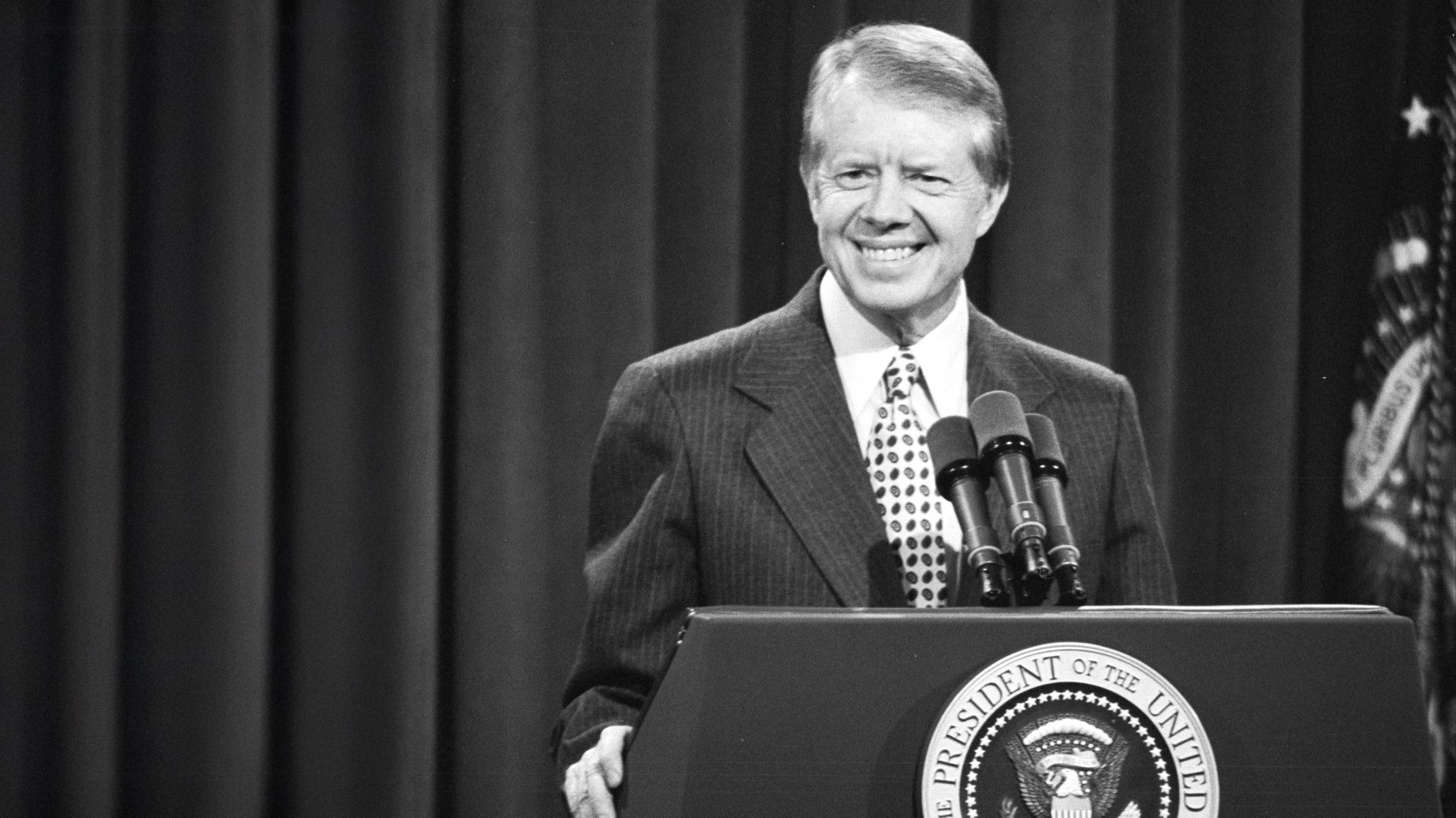

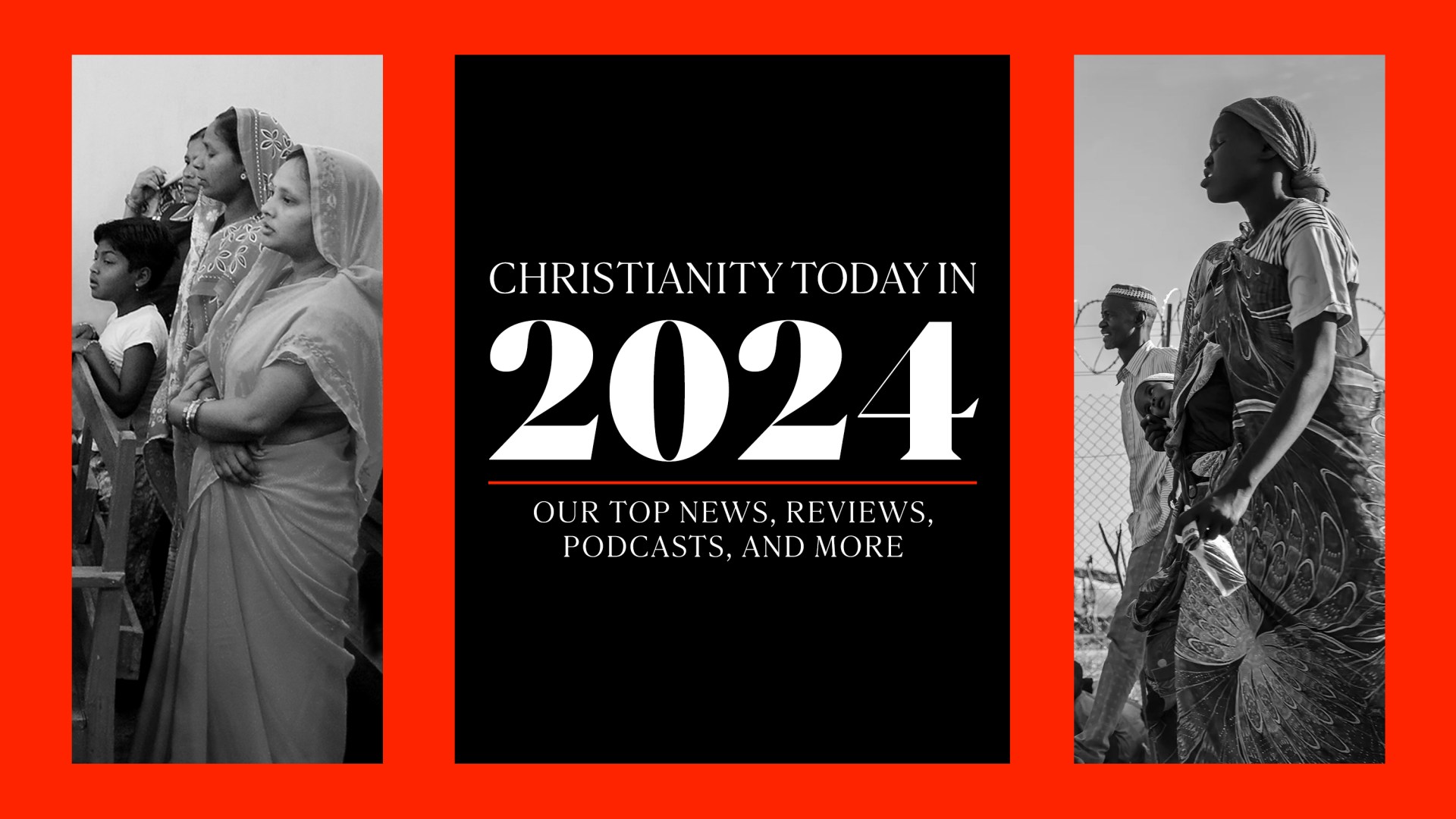

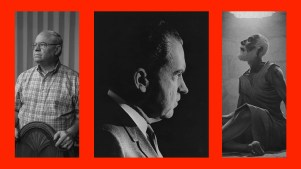

Former US president Jimmy Carter, who rose to the White House as a progressive evangelical outspoken about both Jesus and justice, died Sunday at his home in Plains, Georgia, at age 100.

Carter was the longest-living American president, and he continued to teach Sunday school and volunteer with Habitat for Humanity in his home state of Georgia into his final years.

Growing up a racial integrationist in the Deep South, he was a theologically conservative Christian with a liberal political platform. These incongruities—which hamstrung his politics—made Carter one of the most fascinating evangelical figures of modern times.

In 1976, Playboy magazine printed an infamous interview of Carter, then a Democratic presidential candidate. Those who actually read the titillating interview could easily discern Carter’s piety.

But an overcharged politics seemed to allow only two real options. Secular pundits mocked his prudish confession of “adultery in my heart” and characterized him as a “redneck Baptist with a hotline to God.” Conservative Christians—who would not admit to having read the interview in the pornographic magazine—lambasted his use of the word screw and said someone with the moral character to lead the United States would not have granted an interview to the salacious magazine in the first place.

The interview nearly cost Carter the election. Four years later, still caught between two worlds, he lost reelection. But the fraught nature of Carter’s presidential career was nothing new.

A child of Plains

Carter’s childhood set him up to challenge categories. By many measures, Plains, Georgia, was a typical Southern town during the Great Depression. The area was not prosperous, and Carter grew up in a home without running water, electricity, or insulation. It was politically conservative, and many local whites joined the John Birch Society. It was also racially segregated. When young Carter and his Black friends approached the pasture gate to go hunting and fishing, his friends always stepped back to allow the future president to go through first in an act of racial deference.

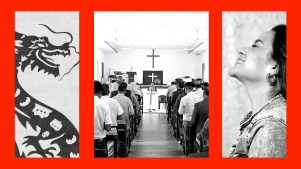

A conservative evangelical culture also pervaded Plains. Carter spent his childhood trying not to swear. He attended a Southern Baptist church where he was born again and later rededicated his life to Christ. As a young adult, he took missions trips to Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. As president, Carter witnessed to foreign leaders, urging them to “accept Jesus Christ as personal savior.” This evangelistic streak could be traced back to Plains.

But Plains was beginning to open up to the world. Carter was the first president to be born in a hospital and he would go on to attend the Naval Academy in Annapolis and became a nuclear submarine engineer. Just miles away in Americus, Georgia, was the interracial Koinonia Farm. His devout mother pushed racial boundaries and identified as a feminist. Andrew Young, a prominent civil rights activist, would later say, “All the liberals I had worked with got nervous in a room full of Black people, and Jimmy Carter didn’t.”

Not long into a promising career in the US Navy as an nuclear submarine engineer, Carter defied his young wife’s wishes and his superiors’ aspirations for him. He returned to Plains as a peanut farmer. He succeeded spectacularly in turning around the family business. He launched a long career of civic service. He joined—and then led—farming associations. He served as district governor of Lions Clubs. He courageously served on the Sumter County Board of Education as the civil rights movement ramped up, working to equalize and integrate the public schools.

In fact, Carter was put under immense pressure to join the White Citizens’ Council in the wake of the Brown v. Board Supreme Court decision in 1955. A group of men implored Carter at his warehouse, telling him that every white male adult in the community had joined except him. Despite the threat of a boycott against his business, an angry Carter took a $5 out of his pocket and said, “I’ll take this and flush it down the toilet, but I am not going to join the White Citizens’ Council.”

A drive for justice continued to drive Carter’s foray into politics. In his campaign for the Georgia Senate, he explained that he wanted to “establish justice in a sinful world.” Niebuhrian in his realism, he nurtured a warm evangelical piety, a strong conversionism, and a belief in the separation of church and state.

His Southern Baptist church, however, was not as convinced of the value of politics. “Why in the world would you want to become involved in the dirty game of politics?” asked a visting preacher. Communicating the magnitude of his ambition, Carter responded, “How would you like to be pastor of a church with 75,000 members?”

But the young politician, now age 39, quickly learned just how dirty politics could get. After losing the election, Carter learned that 117 voters had lined up in exact alphabetical order to cast their ballots. Many of them, it turned out, were dead, living out of state, or in prison. With a dogged persistence that would characterize his political career, Carter investigated. The result was reversed.

But the politician was not a saint. While observers lauded his efficient, compassionate, hard-working service as he rose through the political ranks, a sordid pragmatism sometimes emerged.

When Carter ran for governor in 1970, his aides (who called themselves the “stink tank”) ran a particularly unprincipled campaign. In an egregious example of race-baiting, they used a photograph of his liberal opponent Carl Sanders celebrating with the Black members of the Atlanta Hawks after winning a championship.

The photograph was meant to smear Sanders by associating him with alcohol and African Americans. While perhaps less tawdry than many of his rivals’ tactics, it nonetheless was an unblinking use of the so-called “Southern strategy” meant to win votes from segregationists.

Moral minority

But this was not the salient story as Carter’s profile rose nationally. “You won’t like my campaign,” Carter had warned Vernon Jordan, president of the National Urban League, “but you will like my administration.”

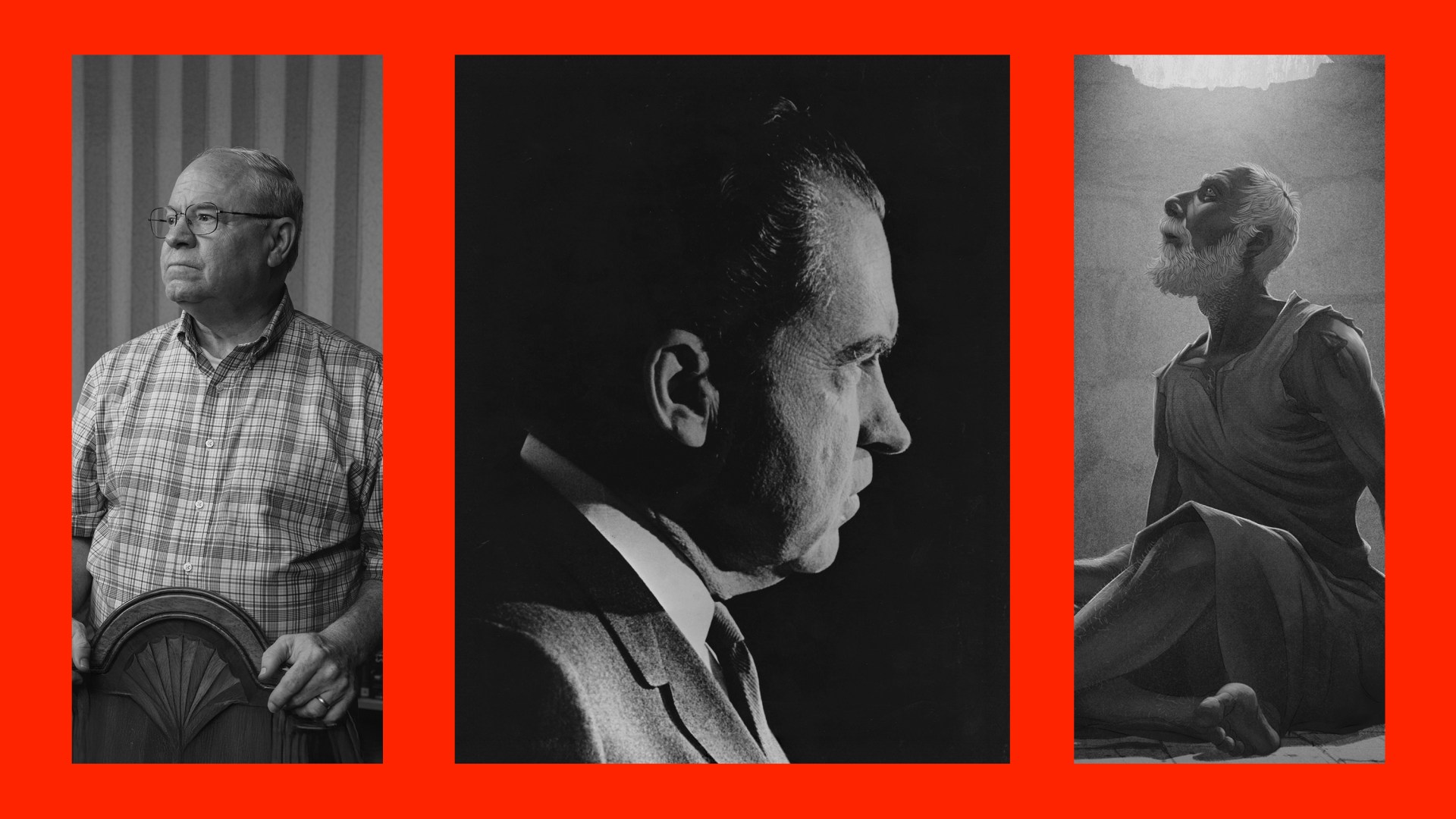

His refreshing gubernatorial administration presented a racially enlightened model of the New South. Moreover, Carter seemed like a model of moral rectitude compared to the foul-mouthed Lyndon B. Johnson and the corrupt Richard Nixon.

He sat on Billy Graham’s platform through the 1973 Atlanta crusade and frequently witnessed to his faith. The governor declared to a convention of Methodists, “I am a peanut farmer and a Christian. I am a father, and I am a Christian. I am a businessman and a Christian. I am a politician and a Christian. The single most important factor in my own life is Jesus Christ.”

This language was not commonly used among politicians of that era, and it appealed to a broad swath of evangelicals who backed his 1976 run for the White House. His centrist proposals on energy reform, the environment, the Panama Canal, and Mideast peace talks, for example, enhanced his standing among a rising coalition of progressive evangelicals who had protested the Vietnam War, worked for racial justice, and voted for George McGovern in 1972.

But most evangelicals were simply delighted that an outspoken, born-again believer was running for president. Evangelicals who had never voted before voted for Carter. Evangelicals who had never campaigned for a candidate campaigned for Carter.

Paeans to Carter emanated from evangelical magazines and presses as soon as he secured the Democratic nomination. Two days after the convention closed, several full-page pro-Carter advertisements appeared in Christianity Today. The first urged evangelical readers to purchase a just-released book called The Miracle of Jimmy Carter.

Another supporter drew a popular poster depicting Carter with long, flowing hair and dressed in biblical garb with the caption “J.C. Can Save America.” The poster insinuated that Jimmy Carter was a political surrogate for Jesus Christ himself.

Carter combined populist evangelical rhetoric with the fear of a lost America. This worked to great effect among evangelicals, who felt like they were on the margins of national culture. “I’m an outsider and so are you. I’d like to form an intimate relationship with the people of this country,” Carter often said during the campaign. “When I’m president, this country will be ours again.”

Evangelicals helped deliver a solid victory for the Democrat over Republican Gerald Ford. In that political and religious moment, it did not seem like a foregone conclusion that evangelicals would mobilize on the right more than the left. Secular elites dominated the Republican Party, whose oligarchs felt little compulsion to kowtow to the desires of religious conservatives.

Moral majority

Carter’s presidency did not rise to the promise of his campaign. Events beyond his control—notably a stagnant economy, high inflation, and diplomatic crises in Afghanistan and Iran—limited his effectiveness in office and sabotaged his campaign for reelection.

Moreover, he hemorrhaged evangelical support. Having enjoyed widespread evangelical backing in 1976 without having campaigned for it systematically, Carter failed to cultivate his most obvious religious constituency. Evangelicals critics noted that Carter failed to hold religious services in the White House or appoint religious conservatives to important executive posts.

Most of all they resented how captive Carter seemed to a Democratic Party veering toward the cultural left, especially on abortion. Generally dismissed as a Catholic issue in this era, abortion was not a dominant evangelical issue into the mid-1970s. But “Abort Carter” pins proliferated late in his term as pro-life evangelicals deemed Carter’s personally-opposed-but-pro-choice approach to be insufficient.

Carter’s equivocations on abortion also increasingly offended those on the political left. In the end, he was impossibly stuck between two diverging constituencies on a long list of issues: prayer in school, taxation of private schools, and the Equal Rights Amendment. Many evangelical leaders bitterly rescinded their support of Carter. After the White House Conference on Families in 1979, Jerry Falwell accused Carter of not being willing to stand up for the “traditional family,” leaving the country “depraved, decadent, and demoralized.”

It was a profound misfortune for Carter—and for a broader evangelical left—to have emerged in an era of hardening party structures and increased enforcement of cultural orthodoxies. By 1980, large chunks of his evangelical constituency had defected to Ronald Reagan, a divorced-and-remarried Hollywood actor.

The irony of it all was that Carter himself had helped to catalyze this political mobilization by rousing a sleepy evangelical electorate. Progressive evangelical Ron Sider quipped that “we called for social and political action, [and] we got eight years of Ronald Reagan.”

A humanitarian giant

Carter left the White House with a reputation as a well-meaning but ultimately ineffective micromanager. In recent years, however, scholars have emphasized his impressive efforts to negotiate the Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel, return the Panama Canal to Panama, broker nuclear weapons limits with the Soviet Union, and advocate for human rights in Rhodesia, Uganda, and many Latin American nations.

His post-presidential career has needed very little rehabilitation. Carter, described by biographer Randall Balmer as a “restless man, consumed by a kind of frenetic benevolence,” has been a strong supporter of Habitat for Humanity, which grew out of Koinonia Farm. The Carter Center, which he founded shortly after leaving office, has sought to confront human rights violations, eradicate disease, and reconcile warring parties in Haiti, Guyana, Ethiopia, Korea, and Serbia. His efforts won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002.

James Laney, the former president of Emory University, which houses the Carter Center, said, “Jimmy Carter is the only person in history for whom the presidency was a steppingstone.”

In the end, Carter revealed the full dimensions of a diverse evangelical movement. For those convinced that conservative theology requires conservative politics, the former president showed that evangelicals sometimes take moderate and progressive views on civil rights, the environment, and gender equality. Carter’s political career also showed significant limits. This progressive evangelical may have reached the highest office in the nation, but he was left behind as backlash from his own people hamstrung his presidency and sabotaged a potential second term.

The tensions resulting from such high political visibility have largely resolved. The passage of time, the achievement of humanitarian triumphs, and the genial specter of an old man hammering nails and teaching Sunday school in rural Georgia granted Carter the blessing of a long farewell to a remarkable life.

David R. Swartz teaches history at Asbury University and is author of Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism.