One Sunday when my son was a baby, a woman approached me (Seana) at church. I dreamed of changing the world for Jesus, but I had exchanged traveling the globe as a missionary for perpetually changing diapers and scrubbing dishes in the suburbs. The woman declared, “I am so glad you are staying home. Motherhood is your highest calling.”

At the time, this felt true—I’d left a career I loved to stay home with my child. Yet this woman had seemed to shrink all my gifting and capacity for serving Christ into one role and season of life. And sadly, I held on to that comment as if it had come from the mouth of God. So when motherhood with a neurodiverse child failed to fulfill my longing for wholeness (as some Christian parenting books taught me it would), I felt I was failing both as a woman and as a Christian.

Early on in my married years, I (Sandra) identified more with Ramah, convulsing over the innocents that Herod ordered killed, than with the little town of Bethlehem. For ten Christmases, infertility and multiple pregnancy losses attuned my heart to “Rachel weeping for her children and refusing to be comforted, because they are no more” (Jer. 31:15–22; Matt. 2:16–18).

My husband and I had adoptions fall through on December 22—two years in a row. So amid the aroma of gingerbread and the sight of twinkling lights, we shut the door to the nursery and tiptoed away, exchanging dreams for empty arms. The deepest pain of all came from my failure to live out what I perceived then as God’s highest calling for every woman: motherhood.

And after the successful adoption of our daughter, who is now a mom herself, I wore the hat of a work-from-home mom all through her childhood. As my daughter grew, I needed to revisit where and why I owned the view that God had only a maternal vision for godly womanhood.

Over the years, the two of us—a work-from-home mom of three and a seminary professor and grandmother—wrestled with these important questions: Is motherhood truly every Christian woman’s highest calling? How did Christ view motherhood? Was motherhood the highest calling for women in the early church? If motherhood isn’t a woman’s highest calling, what is?

In the process, we’ve read stories of ancient Christian women and explored how the biblical ideal of womanhood differs from some of the heralded visions of motherhood in modern evangelicalism. And what we found was that both the Scriptures and early church history can help realign some of our off-kilter views about a Christian woman’s “highest calling” in the modern church.

Let’s start with the universal female ancestor, Eve, whom the Bible hails as “the mother of all living” (Gen. 3:20). In the first chapters of the Genesis narrative, we see how God creates our first parents to rule together and to fill the earth with image-bearing worshipers of God (Gen. 1:28). In this way, male and female humans shared the same mandates of ruling and multiplying.

Although parenthood was part of how Adam and Eve were meant to glorify God and partner together to multiply image bearers, nowhere in these early chapters of Genesis do we find language that suggests having children is a woman’s highest good. And in the New Testament, instead of finding a reiteration of the Genesis mandate to multiply humans, we find Christ issuing a similar mandate to multiply worshipers by making disciples (Matt. 28:18–20).

Now, let’s turn to the next most famous mother of all time, who birthed the God made flesh—Mary, “the God bearer,” as the Council of Ephesus (AD 431) called her.

In Luke’s gospel, the angel Gabriel visits Mary and prophesies that she would birth a child conceived by the Holy Spirit (Luke 1:30–33). Mary’s motherhood to Jesus throughout his life was an honor which played a vital role in the provision of salvation for all of humanity. It’s clear that God ordained parenthood, including Joseph’s role, as part of his miraculous plan.

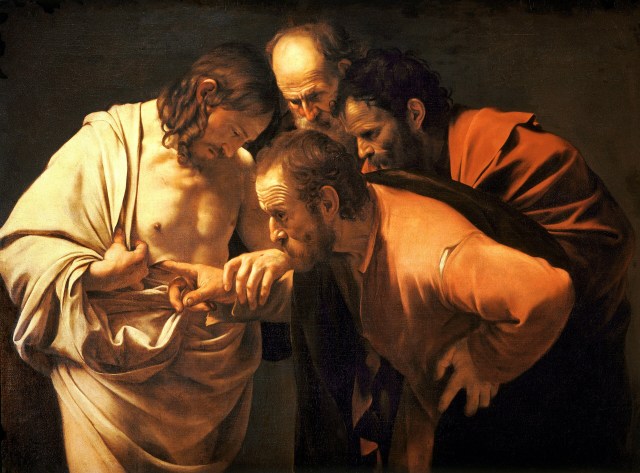

As we continue following the story of Mary, we arrive at the scene where Jesus is grown and ministering to a crowd of people. As he is teaching about the kingdom and speaking against the legalism of the Pharisees, someone in the crowd interrupts him to say, “Your mother and brothers are standing outside, wanting to speak to you.”

In response, Jesus asks, “Who is my mother, and who are my brothers?” Pointing to his disciples, he says, “Here are my mother and my brothers. For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother” (Matt. 12:47–50).

By this, some people might think Jesus is dismissing or putting his mother down. But by Jesus’ own definition, Mary would have been included in the group of family members he affirms. Did she not tell Gabriel, “I am the Lord’s servant. … May your word to me be fulfilled”? (Luke 1:38). Did she, of all people, not agree to align her will with God’s will?

Still, Jesus reframed what is most valuable in his kingdom, which is not a natural relationship bound by blood—though family can be one of God’s greatest blessings—but rather a mutual kinship defined by obedience to the will of God. When seen in this light, Mary’s calling of motherhood to Jesus was secondary to her ultimate belief in and obedience to her Son.

Then there’s the familiar story of Mary and Martha. Martha is doing all the traditionally feminine tasks, while her sister, Mary, sits at Jesus’s feet—taking the bodily stance of a first-century disciple before a rabbi. Martha accosts Mary, expecting her help with domestic tasks. But instead of sending her back to the kitchen, Jesus affirms Mary for choosing “what is better” (Luke 10:42).

From the Lord’s own example, we learn that the highest calling of any person—regardless of marital or parental status—is to follow him. And the highest calling of a disciple is not to make children but to make disciples (Matt. 28:18–20). Sometimes the two will overlap—for example, both of us have labored to disciple our children in the faith. But our disciple making extends far beyond hearth and home into building up the church to fulfill its calling as the body of Christ.

In her article for Christianity Today, Jeannie Whitlock writes about how her birthing a child reminded her of the church: “Our bodies are as crucial to God’s plan as Mary’s was. Like Mary, whether single, married, parents, or otherwise, we are called to bear Christ’s life into the world.”

Paul honors many women for their faithfulness to the gospel. Of the 29 people Paul greets in his letter to the Romans, 10 of them are women. We find names like Phoebe—deacon of the church in Cenchrea—and Prisca, or Priscilla (more about her later). We read about another Mary, who some believe refers to Mary Magdalene. There was also Junia, prominent among the apostles, and Julia, relative of Philologus. Tryphena and Tryphosa were workers in the Lord. Paul honors both Nereus’s sister and Rufus’s mother, who was like a mother to Paul.

Of these ten, only one was honored for her biological motherhood, yet all were recognized for their faithful service in the kingdom.

The apostle Paul encourages young widows to marry, to have children, and to manage their homes (1 Tim. 5:14). He writes that “it is better to marry than to burn with passion” (1 Cor. 7:9). He also honors the faithfulness of Timothy’s mother and grandmother (2 Tim. 1:5). Yet nowhere does he hint at marriage or motherhood being a woman’s highest calling. In fact, in his letter to the Corinthians, Paul famously encourages believers to remain single for the work of the gospel (1 Cor. 7:8–9). For him, “to live is Christ and to die is gain” (Phil. 1:21), and so it should be for us.

To understand how women in the first-century church viewed their callings, we turned to the Book of Acts. There, we found that when women appeared in the text, it wasn’t because of their roles as mothers but because of their gifts to strengthen the church. Priscilla, together with her husband Aquila, taught the skilled preacher Apollos (Acts 18:24–26). If Lydia, a prominent businesswoman, was a parent, the text does not mention it. Instead, she was recognized for leading her household to faith and for her hospitality (16:14–15). And the unmarried daughters of Phillip were mentioned for their exercise of the gift of prophesy (21:8–9).

If motherhood were truly a woman’s highest calling, wouldn’t we find the women of Scripture honored foremost for their motherhood rather than for their service to God’s kingdom? But that is not what we find. Yes, Christian women who married and had children were called to love and care for their families well, yet this work was seen not as their primary calling but part of fulfilling their ultimate call to follow Christ.

When Paul lists qualifications for an older woman to be placed on the “list of widows” cared for by the church, he advises she be “well known for her good deeds, such as bringing up children, showing hospitality, washing the feet of the Lord’s people, helping those in trouble and devoting herself to all kinds of good deeds” (1 Tim. 5:9–10). Of that list, only one point is related to motherhood.

Paul also doesn’t specify that the children the widows raise need to be biological (most children would be fully grown by the time their mothers reached the prescribed age of 60!). In fact, many of the widows who are “really in need and left all alone” are likely not biological mothers at all, since Paul says those with children and grandchildren should be cared for by their own families instead of the church (v. 5).

The apostolic instruction was so clear in this and other passages that male leaders in the early church acknowledged a legitimate office (clergy) for an “order of widows” in the Apostolic Consitutions, an ancient manual of church order used in the third century.

We see the same pattern of discipleship over motherhood in early church history as well. When a third-century noblewoman, Perpetua, became a Christian through the testimony of her servant, Felicitas, the authorities threw them into prison. The young Perpetua had an infant son, whom she was allowed to nurse in her cell. But when she was told to either recant her faith in Christ and worship the Roman gods or die and leave her child motherless, she chose death over her child because her highest allegiance was to Christ. While in prison with her, Felicitas gave birth and also chose to leave her infant in the care of her local Christian community rather than recant. Imagine the gut-wrenching pain of these decisions!

Perpetua’s anguished father even tried changing her mind multiple times, but she responded that only by devoting herself to Christ and his glory would she remain a “perpetual daughter.” If motherhood were truly a Christian woman’s highest calling in the early church, such heroines of our faith would or should have chosen their marriage and family over dying for Christ.

Such stories inform how I (Sandra) pray for and care for my daughter, her husband, and their daughter, and how I (Seana) find fresh perspective on motherhood with my kids still at home. Following Christ led our mothers of the faith into the arena, whereas following Christ leads me to my kitchen sink, laundry piles, and dinner discussions about the Marvel universe. Whatever arena God leads us into, we sacrifice ourselves to serve the Lord as our highest calling. And regardless of parental status, all women in our churches today can be nurturers of faith.

Especially in this holiday season, when we hear someone ask the dreaded question “When will you have children?” of our childless friend, will we intervene? When we see an exhausted mother, will we choose to say something besides “Motherhood is your highest calling”? Or when we feel we must bake dozens of cookies, attend every festival, and decorate the tree as if it’s on display at Magnolia Market to be the perfect mother—will we miss attuning our hearts to the presence of our Savior and serving him? Will we be like Martha, fixated on fulfilling all that our culture expects of us as women, or will we prioritize sitting at the feet of Jesus like Mary?

Ever since the angel’s announcement to Mary, following Christ has been every woman’s highest calling. And whether or not we end up being a wife or a mother, we can all become perpetual daughters of God.

Sandra Glahn is a professor at Dallas Theological Seminary, president of the Evangelical Press Association, and the author or coauthor of more than 25 books. Seana Scott is a writer, speaker, and content creator passionate about disciple making.