This New Year, the algorithms promise a new you. New diets, new fitness routines, new products. What better time to get on top of self-care?

But it’s not just in January that social media idealizes our existence. All year, users are bombarded with impossible standards in the most mundane parts of life, from skin-care regimens to nighttime routines and aesthetic cleaning practices. Parents watch moms picking up their children’s toys during naptime and feel defeated. Influencers share easy tips for a perfect complexion, and viewers who don’t have “good skin” get discouraged.

Dreaming about ideals can offer a comforting sense of control. Perhaps it really is attainable to have children nap through the afternoon, long enough to allow for meal prepping that sustains an entire week without a run to Chick-fil-A. But there’s also a danger to how much we idealize what could be—especially when it comes to our faith.

As a single woman, I often think about marriage and motherhood. I imagine what it might be like to raise children with someone whom I love and who loves me. I can envision my dream home and dream wedding; I know my future children’s names. (My Pinterest boards put all this on full display.) But building my faith on getting married and becoming a mother isn’t sustainable. This view of the future ties God to promises he never made, staking my faith on fragile ultimatums.

Of course, social media doesn’t help. When I log into Instagram, I don’t just see influencers. I see my peers: getting engaged, getting married, having children, buying homes, adopting dogs. Now that it’s been a few years since graduating college, I feel more dread as people younger than me live the life I had pictured for myself.

There are days when I am so discouraged with my reality in comparison to the pictures I see that I wish I could go back in time and try again.

Christians sit in an often-uncomfortable position between the two comings of Christ, which means we hold the realities of sin and hope in tension. Jesus died on the cross and rose again, and we are redeemed. Still, we are faced with daily reminders of the fallenness of the world. As the Nicene Creed says, “We look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come.” We also look to a good night’s sleep, a healthy body, a quiet mind, a warm home, an adored spouse, and a beloved child.

That looking isn’t inherently bad. Suffering in the Psalms, David both looks to the past for reminders of God’s faithfulness and anticipates a new day. Take Psalm 77: “I will remember the deed of the Lord; yes, I will remember your miracles of long ago” (v. 11). And Psalm 84: “My soul yearns, even faints, for the courts of the Lord; my heart and my flesh cry out for the living God” (v. 2).

As Christians, we are constantly both remembering Jesus’ good news and longing for the kingdom to come. We know Jesus will arrive again and the whole world will be restored. But we don’t quite know what that restoration will look like—or, in the meantime, how restoration will play out in our own lives. God wants good things for us, but social media makes goodness a moving target.

The pitfall for us as Christians is when idealization becomes idolization—when ideals become our expectations, when we put our hope in versions of life that are not promised.

This is exactly what social media algorithms do. They’re designed to dissatisfy, creating a chasm between where we are and where we want to be, insisting that material possessions or proper routines can solve our problems and that success looks the same for everyone. The algorithms beg us to keep consuming content that heightens our sense of not being or having enough.

There’s nothing wrong with building good habits. But the right workout routine, the right diet, the best skin—even the dog and the house and the spouse—can’t fix the dissonance between right now and the ideal life.

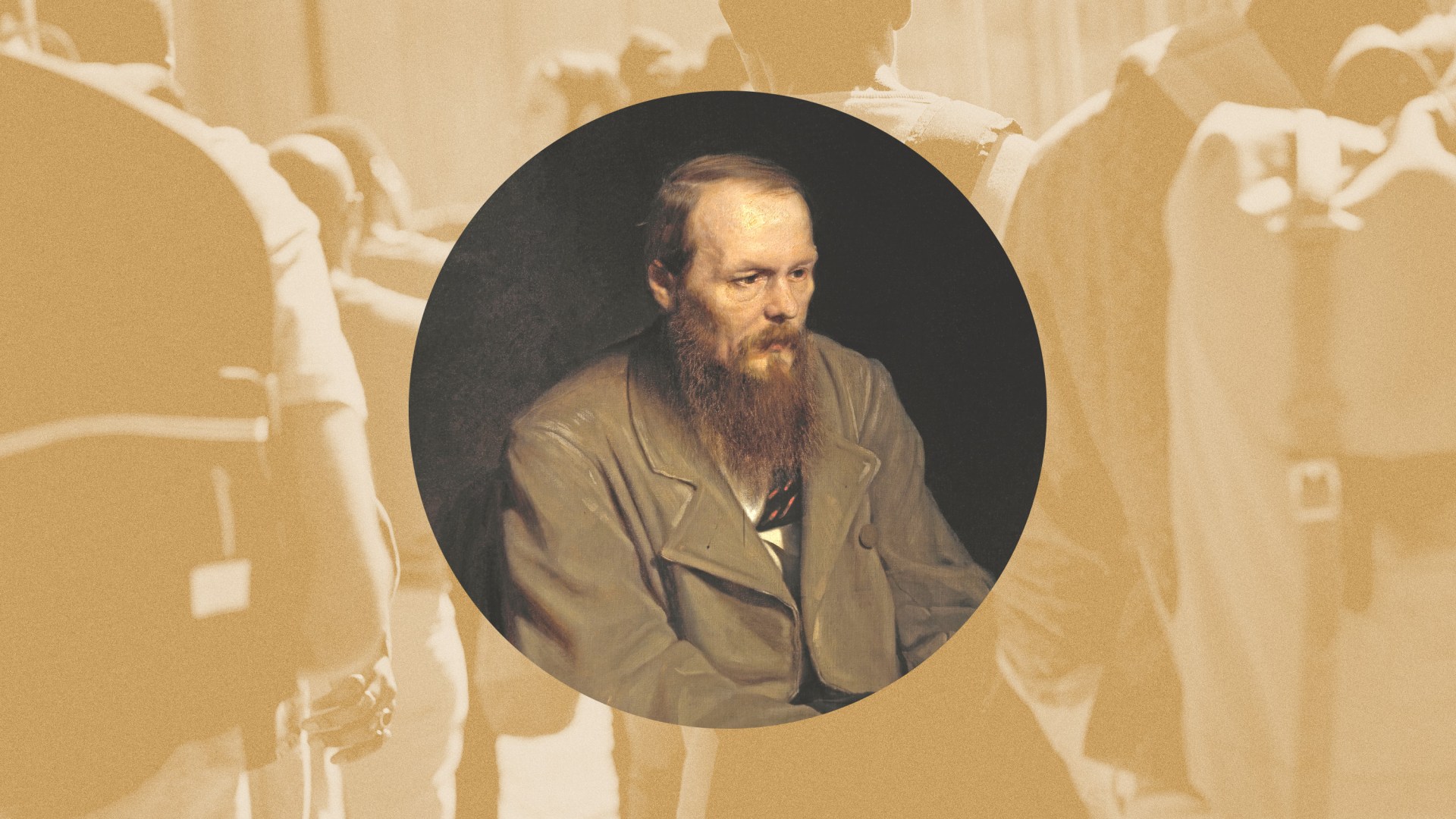

Ecclesiastes, characterized by its pessimism and wrestling with human purpose, is not my default for inspiration. But this New Year, I’m drawing a certain peace from the book’s conclusion.

After scouring the earth for wisdom, the author concludes that all on earth is vanity. (The Hebrew word for vanity, hevel, is used almost 40 times in Ecclesiastes; the phrase vanity and a striving after wind is repeated 7 times in the ESV.) Hevel means “figuratively, something transitory and unsatisfactory” and “vapor or breath.”

Vanity is not only self-indulgent but also fleeting. The same word is translated as idols in other Old Testament passages: In Deuteronomy, Moses recounts the Hebrews’ rejection of God in the wilderness (32:21), and in 1 Kings, this word describes the failure of the kings of Israel (16:13, 26). Vanity is used in Job to describe his friends’ empty words of advice (21:34; 27:12).

Ecclesiastes’ incessant repetition drives home one of the main points of the book: Human ways are disappointing, and placing our hope anywhere besides God is futile.

In other words, striving for the picturesque scenes that I see on social media, whether posted by influencers or friends, isn’t necessary. What I can do, what I can control, is to love God and keep his commandments. Leaning into obedience will make me into who he wants me to be and will send me where he wants me to go—which might not be into the kind of life social media encourages me to desire. But social media is not my measure of success.

After seeking wisdom all his life, the author of Ecclesiastes concludes by pointing us to the only constant: God. God is our provider, not only of material needs but also of peace. “Now all has been heard; here is the conclusion of the matter: Fear God and keep his commandments, for this is the duty of all mankind,” he writes. “For God will bring every deed into judgment, including every hidden thing, whether it is good or evil” (12:14).

The online content machine tempts us with stopgap solutions to metaphysical problems. But in the grand scheme of the history of the world, the things we are chasing after here—clear skin, a clean house that stays clean, a hyperfixation meal that I don’t get tired of after a week, or a perfect meet-cute—are dust (Ecc. 3:20). God does not expect us to solve our existential anxiety by means of productivity and striving, seeking always to return to what we had before or looking to what we covet next. He asks us only to follow him and love others.