Alissa's note: This reflection is part of a series on "Watch This Way" called "Rewind," in which movie critics and film buffs reflect on a film from the past and what it means today.

Carousel was famously cited by Time magazine as the best stage musical of the 20th century. Composer Richard Rodgers allegedly called it his best work. The film version earned nominations for its director (Henry King) and writers (Phoebe and Henry Ephron) from the Directors Guild and Writers Guild respectively. It has a lofty 7.0/10.0 rating from nearly 4,000 viewers at IMDb. In other words, it is one of the most esteemed musicals of all time and one of the most beloved films from the 1950s.

Huh?!

Watching Carousel today, at a time when football players are being suspended for domestic violence and documentarians are striving to give a voice to our some of society’s most vulnerable members, is a bit like taking a Shakespeare class and trying to convince yourself that The Taming of the Shrew is not misogynistic or that The Merchant of Venice is not anti-Semitic. One wants to avoid charges of ethnocentrism at all costs, but it is hard to look at the film and feel anything but embarrassment that our society once countenanced such tripe.

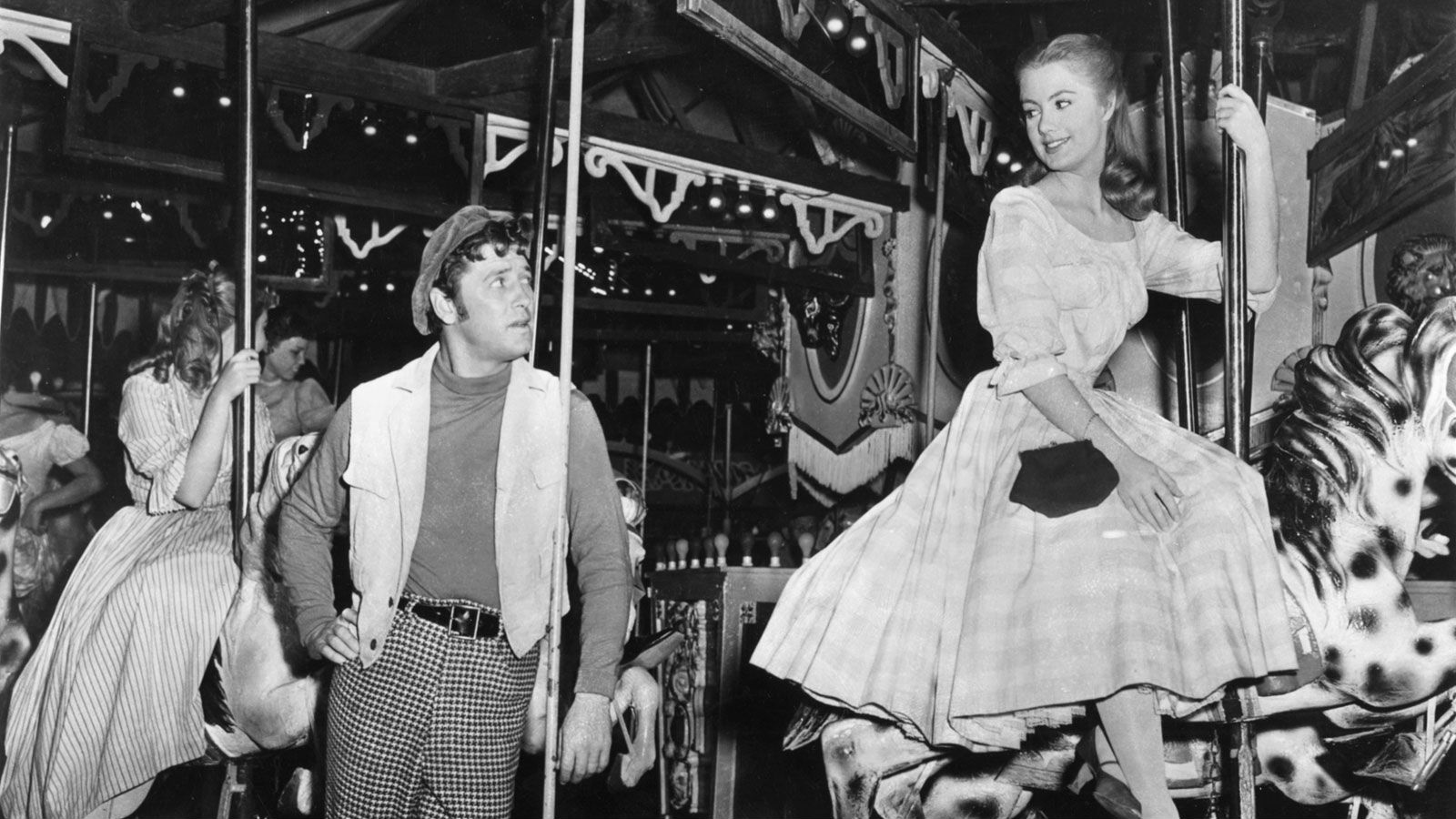

The film opens with Billy Bigelow (Gordon McRae) at a way-station outside of heaven. He has not been judged too harshly for a life lived beating his wife, Julie (Shirley Jones), and sponging off her aunt or for dying while attempting to rob a rich man at knifepoint. If I didn’t have larger complaints, I might be tempted to examine more seriously the theological implications of this purgatorial setting, but other than a brief mention that Billy’s partner-in-crime Jigger didn’t even make it “this far,” the film doesn’t invite us to take seriously the notion that our status in the afterlife contains any sort of judgment of our life on earth.

One of the rules of this way station is that each person has the “right” (odd word, that) to return to earth for one day. Billy long ago waived that right but now he has heard that the wife he left behind and the daughter he never met are in need of his help. (She never needed his help in the 18 or so years he’s been lounging about polishing stars?) Before he can go, though, he needs to tell his story, so we flashback to the beginning.

The story, while long in the telling, is pretty thin. Billy, a carnival barker, woos a pretty girl from the mill. She impulsively agrees to marry him—did they just meet?—and he is fired by his jealous boss. Despite Julie’s best attempts to be a submissive, cheerful, and supportive wife, Billy does everything in his power to make her (and everyone around him) miserable. He refuses a job on a fishing boat because he doesn’t like the smell and thinks the work beneath him.

He protests that he doesn’t “beat” Julie, he only “hits” her.

When asked why he strikes his wife, he says that there comes a point in every argument where he realizes she is in the right, so that’s when he hits her. He hesitates to join his pal, Jigger, in a larceny plan, but then he promptly gambles away his stake in the robbery over five minutes of blackjack.

When he finds out his wife is pregnant, Billy burst into song about how great it will be to have a son. Then it occurs to him that the kid might be a girl. Oh, no! A son can be a playmate and a source of pride. A daughter is just one more burden; the reason you have to embark on a life of crime so that you can afford to give her pretty things.

The most common defense of Carousel is that while the story may be dated, the music is beautiful. Certainly the dance around “June is Bustin’ Out All Over” is great as a showpiece, right up there with some of the routines from Seven Brides for Seven Brothers.

But to the extent that they are actually integrated into the narrative, the songs either reinforce the problematic themes (“What’s the use of wondering / If the ending will be sad? / He’s your feller and you love him / There’s nothing more to say”) or are ironically undercut by them. The film’s anthem, “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” is inspiring outside of the context of the play, but the reality is that Julie is left alone, both to walk and to care for her daughter.

Okay, Billy is a jerk, fine. What’s a redemption story without a hero that has been brought low? But the last act of Carousel is the most mind-boggling. Billy returns to earth to find his daughter, on the verge of graduation, unhappy and looked down upon by her rich neighbors. He appears to her—he is visible only when he want to be—long enough to try to give her a star and (yep, you guessed it) pop her a good one when she refuses to accept it.

By the time his daughter comes out of the house with Billy’s widow, he has retreated to invisibility. His attempts to alleviate his family’s distress have failed miserably, but it’s okay because Louise reports wondrously to her mother that when the mysterious stranger struck her, it didn’t hurt at all. “Is [that] possible?” she asks her mother.

“It is possible dear, for someone to hit you, hit you hard, and it not hurt at all.” That’s the film’s thesis, delivered by Julie to her daughter, and it’s hard today not to see the results all around us, every day, of young girls being taught that physical pain and humiliation is an acceptable price to pay for a little attention from (I won’t say “the love of”) a not so good man.

You’ve come a not-so long way, baby. We no longer think it is your fault if he beats you. It’s only your fault if it hurts.

Kenneth R. Morefield is an associate professor of English at Campbell University. He is the editor of Faith and Spirituality in Masters of World Cinema, Volumes I & II, and the founder of 1More Film Blog.