In my art history classroom, I dim the lights and turn on the projector. The image pools on the screen at the front of the room. The heaviness of another news cycle, along with my own family’s fragile health, weighs on me like the thick, damp fog blanketing the college campus where I work. But along with my students, I begin searching the picture on the screen.

We are not looking for a hidden Da Vinci Code cipher or a proof of artistic genius. As we study images of crisp frescoes and architectural ruins, we are seeking out the ripples of Christ’s incarnation.

“The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us,” the apostle John writes (John 1:14). Jesus, the eternal God, born of a woman, settles in our material, temporal existence. The Incarnation dignifies and reaffirms God’s commitment to the world that he made and that he promises to make whole again. He does not abandon us to our despair but enters into it. Humans’ ability to make art—to materialize meaning—is an echo of not only a creator God but also an incarnate God.

As I leave the classroom, the day’s weightiness still hovers, but it is also pierced. Again and again, art renews and expands my wonder over the miraculous reality of the Incarnation: God with us, a light shining in the darkness. The art I love best invites me to hold things in paradox.

As theologian William Dyrness writes, “[Art] shows us something we can learn in no other way.” Two very different artworks that reference “God with us,” made hundreds of years apart, suggest both the challenge and possibility of this endeavor.

Learning from art in this way might not come easily to us. Our limited expectations of how works of art function might also truncate our understanding of the Incarnation.

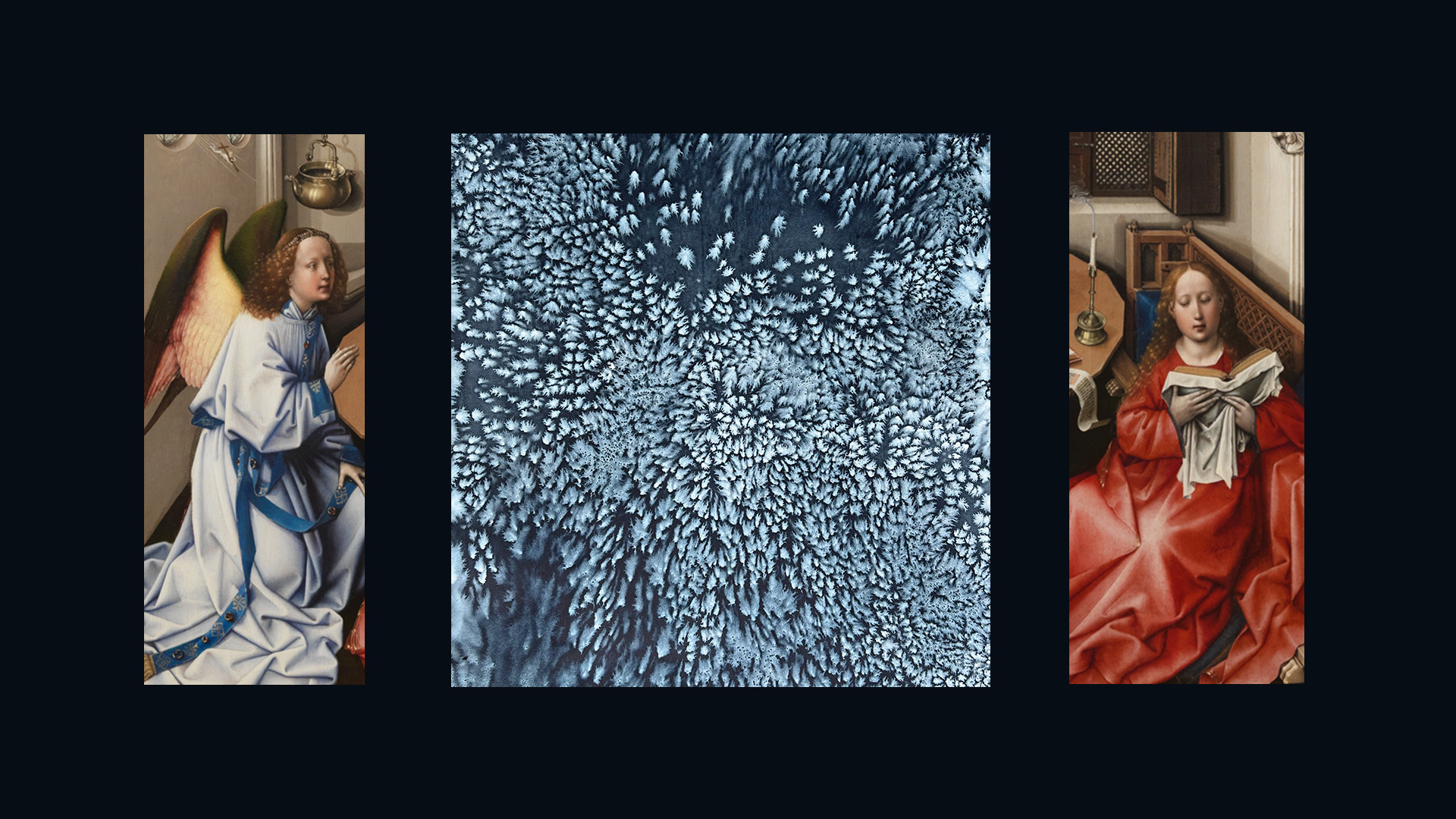

Take, for example, the Annunciation Triptych, a 15th-century altarpiece made for a Flemish home by the workshop of Robert Campin. The center panel of the small devotional object depicts Gabriel’s announcement to Mary. The archangel kneels on the left side of the composition and addresses a seated Mary. We can almost hear Gabriel speaking the words from Luke’s gospel: “You will conceive and give birth to a son, and you are to call him Jesus” (1:31).

Meanwhile, Jesus himself—represented as a miniscule alabaster-white infant carrying a tiny wooden cross—bursts through a window above Gabriel’s head and zips through the air on a sharp, downward diagonal. If we trace the implied line of his descent, we find that he is heading straight for Mary’s womb. To our 21st-century eyes, it is an incredibly strange, even humorous, image.

We might think that the artists of the Annunciation Triptych are offering us an extremely literal illustration. It’s as if they thought, Well, the Incarnation is God with us, so here’s a picture of God on his way to be with us. Very little imagination is required; the painting’s meaning appears to sit on the surface.

The Met

The MetWe may interpret the painting in this way because we are familiar with pictures that directly tell us something: Advertisements and explainer graphics constantly announce what we should buy, who we should desire, and how we should think. If that is what we expect of images, then that is all we will see in the Annunciation Triptych. And thus, Incarnation becomes limited to a specific narrative moment rather than functioning as a cosmic folding of time and eternity. Wonder trickles away, absorbed by a dogmatic diagram.

There is much more to see in the Annunciation Triptych. But first we need a better way of seeing. Visual artworks do not merely tell us things; they can also form us.

The work of California-based contemporary artist Julia Hendrickson also invites us into the wonder of the Incarnation. Hendrickson is a Christian, and her practice emerges from her faith commitments.

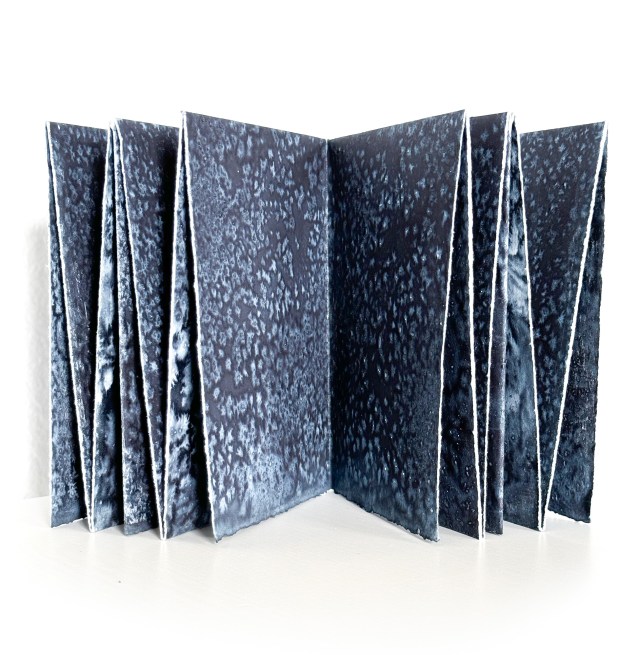

In Hendrickson’s abstract watercolor paintings, feathery tendrils spread like frost across indigo fields. Nets of light pierce midnight clouds. Stars shimmer on a dark pond. We are looking, it seems, at both the entire universe and the tiniest sliver of reality, something that is simultaneously a magnificent galaxy and a magnified drop of water. Our imaginations prickle. What else are we looking at? What artistic alchemy made this possible?

The first paradox of Hendrickson’s work is how she mines seemingly endless variation from a limited process and set of materials. Much of Hendrickson’s daily work follows a rhythm that she frequently documents and shares online. She soaks her thick white paper with wide brushstrokes of water. Then, she repetitively brushes, dabs, or splatters a single hue of watercolor: the warm blue of Payne’s grey.

Finally, while the surface is still wet, Hendrickson sprinkles salt on the pooling paint. The salt crystals both repel the pigment and absorb excess water, resulting in strange and varied starbursts that often reveal the underlying gestural marks of Hendrickson’s initial brush.

As the paint dries, forms shift and fractal patterns emerge. Though the process is purposefully repeated, the results vary in myriad, surprising ways.

This may seem counterintuitive. We tend to despise limitations, especially those in our own bodies. But in his incarnation, the Creator accepts the good boundaries he placed upon his creation. Theologian Kelly Kapic writes that “God is not embarrassed by the limitations of our bodies … but fully approves of them in and through the Son’s incarnation.” I struggle to accept this truth. But when I stand in front of a long gallery wall, covered edge to edge with dozens of Hendrickson’s Droplet paintings, each one different from the others, I marvel at how the God who enters into our humanity continues to multiply unimagined possibilities within its bounds.

A second mystery Hendrickson embraces is the entanglement of the material and the spiritual. Hendrickson began making these process-based paintings while she was in seminary. During that time, one of her friends was about to undergo a serious medical procedure. Anxious and scattered, Hendrickson struggled to pray with words. She turned to paint and paper, ordering her breath and her brush marks as an “integrated prayer.”

Hendrickson calls her practice opera Divina, or “holy work.” The term she coined builds on the Benedictine order’s motto of Ora et labora—“pray and work”—by asserting that our work itself can be a prayer. The movement of her hands across the paper, the slow swirl of paint, the sprinkling of salt, and the quiet waiting are themselves, she writes, “an intentional initiation of a conversation with the Divine.” Invisible offerings of praise, lament, confession, and petition take on material form.

Third, Hendrickson teaches us to anticipate transformation. John tells us that the Incarnation is the light shining in the present darkness (John 1:5). Hendrickson’s time-lapse videos of her painting process begin with the deep blue-gray pigment bleeding across the white paper. But then, when the salt crystals land on the wet surface, the midnight expanse is split open by glimmering light. The darkness is shattered. We wait, and we watch.

More recently, Hendrickson has begun tearing her paintings. She folds the large sheet of paper into 16ths, then unfolds it again and carefully tears along the horizontal creases. She stops three-quarters of the way across the paper then moves to the next row and tears in the opposite direction. Finally, she folds the entire sheet in a meander fold, resulting in an accordion-like booklet. Hendrickson thus transforms her two-dimensional paintings into three-dimensional objects.

She does so while maintaining the paintings’ integrity. They are not torn into separate pieces, nor is anything added to them. They are still paintings, and they have now become—as Hendrickson names them—prayer books.

When I watched her do this for the first time, my heart stuttered. What a strange sight, to see an artist ripping a beloved work. But she did not destroy it; she remade it.

The paradoxes of Hendrickson’s work stretch my own theological imagination. The Incarnation is not God momentarily slipping into a human skin. Perhaps it is more—yet not completely—akin to the way that the salt and pigment and water all remain themselves yet are utterly and mutually transformed. Perhaps it is more—yet not completely—akin to a painting that has been broken and resurrected.

I cannot claim to understand the doctrine of the Incarnation more rationally or thoroughly after spending time with Hendrickson’s work. But these paintings do expand my capacity for awe. I can more joyfully yield to this mystery: “In Christ all the fullness of the Deity lives in bodily form, and in Christ you have been brought to fullness” (Col. 2:9–10).

We now return to the 15th-century Annunciation Triptych.

Using delicate brushes and luminous oil paint, the artists pack this small three-panel painting full of detail. Instead of locating the Annunciation scene against a sacred gold background, as many medieval mosaics do, the altarpiece artists depict Mary and Gabriel in a recognizable 15th-century Flemish home. We see an oval table in the center of the room and a long wooden bench against a large fireplace.

In the right-hand panel, we glimpse Joseph in his carpenter’s workshop, with a city visible through the window. The left-hand panel depicts a walled garden with a Flemish couple in contemporary dress kneeling just outside the door to Mary’s home. The sacred is brought into the mundane.

In addition to the homunculus—the miniature representation of an infant Christ flying through the room—the artists pepper the scene with symbols that would have been familiar to a 15th-century audience. The lilies in a vase on the table are not just decorative; they represent Mary’s purity. A wisp of smoke curls up from a recently extinguished candle. In other artworks from the period, a lit candle represents the presence of the invisible God. But in this painting, that symbol is no longer needed since God himself is now incarnate and physically present.

While the altarpiece ostensibly depicts a particular moment from Luke’s gospel, it actually shows us, as philosopher James K. A. Smith writes, how the Incarnation is “the collision of time and eternity in Christ.” For instance, the mousetraps in Joseph’s workshop point to the end of Jesus’ life on earth. The little wooden contraptions reference Augustine of Hippo’s declaration that “the Lord’s cross was the devil’s mousetrap.” The painters thus present us simultaneously with Christ’s conception and his death.

But the artists also stretch the intimacy of this pivotal moment into their own present. The couple in the left-hand panel are presumably the work’s owners. They are painted with startling particularity: The man has a small wart near the corner of his mouth, and we can see individual stitches on the woman’s wimple. They kneel reverently on Mary’s doorstep, bearing witness to a historical moment with eternal significance. The painting bends time around the Incarnation, folding these worshipers into a present mystery.

Finally, the Annunciation extends its invitation to our own time as well. When we first look at the room in the central panel, we might think that we’ve found a clumsy mistake. Despite the high level of detail, the space does not recede convincingly. The artists do not follow the principles of linear perspective, resulting in a strangely shallow room that appears to be tipping forward. But the effect, when we’re bending down in front of the altarpiece to get a closer look, is that the space begins to enfold us.

Thousands of years after Gabriel’s greeting to Mary and hundreds of years after a Flemish couple bought this devotional object, the painting spills into our present. Incarnation promises to meet us again and again.

“The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us.” These works of art, among others, can translate John’s text into knowledge that reshapes how we engage our present reality.

Both contemporary process-based abstractions and detailed early-modern altarpieces evoke the mystery of the Incarnation; their own strange paradoxes of material and meaning keep us from complacency.

Art helps me be more tender toward all I can’t see in the dark, to believe—even if I can’t comprehend—that the infinite could become an infant and settle here, with me. Art renews my wonder at the wildness of this reality: Christ has come, and Christ will come again.

Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt is associate professor of art and art history at Covenant College and the author of Redeeming Vision: A Christian Guide to Looking at and Learning from Art.