The political choice for American Christians is not between Republican Donald Trump and whomever the Democrats nominate in Chicago this month. It is between Christ and a corrupting, power-centric vision of Christendom.

This decision has confronted believers since we first dreamt of influence instead of the nightmare of persecution. The battlefield conversion of the Roman emperor Constantine created the possibility of using the state to spread Christianity, and the quandary of how to navigate faith and politics, church and government, has not left us since.

Christendom refers to a society or civilization that is not just majority Christian, but one that officially denigrates other faiths and, ironically, poses risks for our own. Though historic versions of Christendom had their benefits—and it is right for Christians to bring our faith and ethics to the public square—this kind of Christian quest for power, even for the best reasons, can eclipse Christ or hamper our witness.

The rise and fall of social and political structures do not reflect the rise and fall of Jesus, who remains eternally on his throne. And though it is possible to pursue Christ and power together, the struggle to keep them in perspective is constant.

That struggle is vividly evident right now among politically conservative evangelicals in America. Since the 1970s, the Christian Right has acquired access and influence to pass laws and shape the judiciary. Christian Coalition architect Ralph Reed asked for just a “seat at the table” where the real decisions get made, but that seat came at the price of political loyalty. And such loyalty, even in the pursuit of the good, can be twisted beyond what Christian witness can bear.

What follows should not be taken as support for Biden’s replacement on the Democratic ticket. Our focus on the Republican Party is not because we believe that Democratic Christians are immune to political temptations or that Christians should be loyal to the Democratic Party. On the contrary, we think misplaced loyalty to any party risks the exchange of hope in Christ for faith in Christendom, and white evangelical support for the GOP has been so overwhelming that this risk feels close to reality.

Our story, however, begins with a Democratic politician—former president Jimmy Carter. In the 1976 election, his campaign decided an interview with Playboy was a chance to showcase God’s candidate to the Devil’s readers. Carter needed to be more than admired. He had to be relatable.

Maybe the interview helped with some voters: Carter squeaked into the White House in November of 1976, as Gerald Ford, his opponent, still carried the stain of the Nixon administration. But Playboy left its own kind of stain on Carter. He spoke about temptation’s grip on the human heart, admitting his own struggles with lust, and used the word screw. Many of his fellow Christians vehemently objected.

“Screw,” said Bailey Smith, a pastor and former Carter enthusiast, “is just not a good Baptist word.” Prominent Southern evangelicals including Harold Lindsell, Jerry Falwell Sr., Jerry Vines, W. A. Criswell, and Bob Jones Jr. all took aim. At one rally, Carter faced a picketer holding a sign that said, “With Christians like Carter, who needs pagans?”

Carter’s frayed relationship with conservative Christians would grow worse during his presidency. These voters were searching for a political lifeboat to survive the cultural flood. Traditional Christianity’s influence was waning thanks to the 1960s counterculture, the sexual revolution, and Supreme Court decisions like Engel v. Vitale (1962), which prohibited school-sponsored prayer in public education. The nascent Christian Right wanted to fight back through politics.

They needed a champion, an avatar of rectitude willing to wage battle in the public square. At a personal level, as a Southern Baptist Sunday school teacher, Carter fit the role. But publicly, he refused to use the government to encourage the kind of clean living he exemplified. He famously said Jesus would oppose abortion, but his administration would not undermine Roe v. Wade (1973). “You can’t legislate morality,” he told Hugh Hefner’s rag. He was not the transformative leader sought by the Christian Right. If the movement’s leaders wanted a revolution, they needed someone able to inspire followers and persuade opponents. They needed the right kind of moral authority—a credible connection of private and public goodness. Carter was not it.

The champion the movement chose in 1980 was Carter’s mirror image: a Republican from liberal California instead of the Democrat from conservative Georgia. In two terms as California’s governor, Ronald Reagan had signed a law that increased abortion rights and opposed a referendum that gave the government more power to remove gay teachers from classrooms. Reagan had also been divorced, and his religious life was more private than public.

But Reagan’s appeal went beyond policy. “The Gipper,” as he was sometimes called, painted a picture of America’s past that gave faith a place of honor, appropriating the biblical simile of a “shining city on a hill” to make the faithful feel seen and comfortable in the new GOP.

Reagan was a pivotal figure in American politics. His calm and sunny optimism made conservatism respectable and attractive. To some extent, this was a boon for the Christian Right, but Reagan’s was a patriotic, ideological revolution more than a moral one. He did not transform attitudes about abortion, gay rights, or even prayer in school among the broader public—yet politically engaged evangelicals stuck with him anyway.

In the Reagan era, “We were somebody. We mattered,” recalled Moral Majority executive Ed Dobson. “All the years in in the backwoods of the culture were over. We had come home, and the home was the White House.”

A decade later, that home was occupied by the first baby boomer president. Democrat Bill Clinton, whose alleged marital infidelity was an issue in the 1992 campaign, was later accused of having a sexual relationship with a White House intern. That story exploded in 1998, and Clinton denied wrongdoing to his Cabinet and, later, the public. He was eventually impeached for perjury and obstructing investigations into his conduct.

Now a vital part of the Republican coalition, the Christian Right actively sought Clinton’s downfall and doggedly emphasized the necessity of good character in public life. “As it turns out, character DOES matter,” wrote Focus on the Family’s James Dobson of Clinton. “You can’t run a family, let alone a country, without it. How foolish to believe that a person who lacks honesty and moral integrity is qualified to lead a nation and the world!” Reed and Franklin Graham, the son of evangelist Billy Graham, would make similar points.

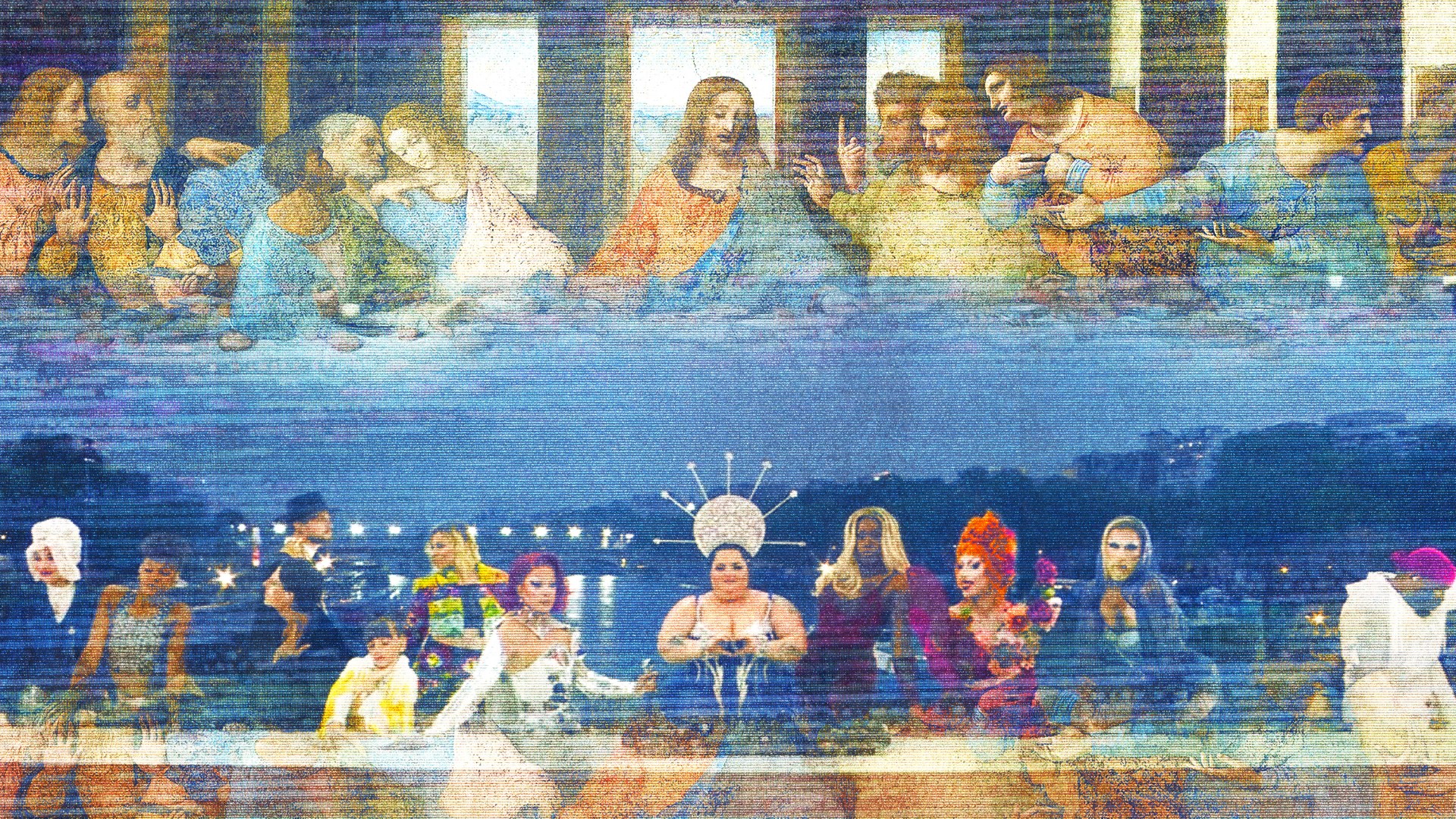

Conservative evangelicals’ intense political clarity in that moment—their vocal conviction that public leadership must stem from private morality and that character is political destiny—infamously would not last. We know the next chapter of this story all too well: On October 7, 2016, a leaked “hot mic” recording of Donald Trump, then the Republican presidential nominee, heard the candidate describing at least his adulterous and vulgar impulses, and, arguably, his habit of sexual assault.

The audio fit patterns in Trump’s past. He was on his third marriage and not only sat for an interview with Playboy but appeared on the cover. He had bragged about extramarital affairs and hurled misogynistic public insults. But his conservative Christian supporters—from pundit Eric Metaxas and megachurch pastor Robert Jeffress to long-standing leaders like Reed, Dobson, the younger Graham, the Family Research Council’s Tony Perkins, and broadcaster Pat Robertson—overwhelmingly did not flinch.

Trump’s then-running mate, Mike Pence, perhaps the most politically successful son of the Christian Right, stayed on the ticket. “I am proud,” he declared, “to stand with Donald Trump.”

The path from “Screw is just not a good Baptist word” to “I am proud to stand with Donald Trump” is longer than the 40 years between those statements. The cultural trends apparent in 1976 had all continued, particularly where sex was concerned. Gay marriage had been legalized, and calls to expand transgender rights and normalize polyamory were growing. It’s easy to lampoon the hypocrisy of the Christian Right’s leaders on the question of character—and they deserve it—but it’s also true that many conservative Christians sincerely felt a heightened sense of cultural doom.

Our major political parties had changed almost as radically. Gone were the days of overlapping coalitions and moderating work across the aisle. Party identities hardened and talk of culture war was joined by fear of civil war.

A politics of persuasion through moral authority may have seemed fanciful in this environment—and electing Trump may have seemed like a rational bargain to establish a conservative bulwark on the Supreme Court, where gay marriage, like abortion nearly 50 years prior, had become the law of the land.

On paper, it worked. Trump’s Supreme Court nominees helped overturn Roe in 2022’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. But Dobbs has left many conservative evangelicals and other social conservatives floundering: Abortion rates have increased nationally; the pro-life cause has suffered ballot box defeats in red states Kansas and Ohio; and Trump’s 2024 campaign has removed support for a federal ban on abortion—as well as opposition to same-sex marriage—from the GOP platform.

Perhaps that decidedly mixed record can prompt reflection. In 1980, Christianity Today ran an editorial on the upcoming election season. It argued for the necessity of a broad issue agenda for evangelicals, one that would reflect the full witness of Scripture: care for the poor and peacemaking alongside pro-life principles and demands for good character.

“Too narrow a front in battling for a moral crusade, or for a truly biblical involvement in politics, could be disastrous,” the editorial concluded. “It could lead to the election of a moron who holds the right view on abortion.”

That wisdom has been ignored. A thin agenda combined with fervent partisan loyalty left many believers feeling like the pursuit of Christendom through the Republican Party was their only option. That loyalty encouraged Christians to defend what was indefensible only a few years before. Continued loyalty requires even more.

In Matthew 10:16, Christ sends out his disciples as “sheep among wolves.” This is an apt description of the Christian’s peril in the field of politics. It is often a dirty game, full of compromise and complications. But the stakes and danger of the game are no excuse to ignore, defend, or grow comfortable with sin.

In the same passage, Christ commands that his followers be “wise as serpents and innocent as doves.” Our shrewd loyalty must sometimes give way to holy innocence. A Christian life of integrity is lived behind closed doors as much as in the public square. This is our best and most persuasive witness (John 13:35; 14:15), and practicing honor, respect, submission, truth, and love of enemies as political virtues is the best way for us to wield power. Opposition to abortion is critical, but it cannot be the only political outworking of our loyalty to God and his Word.

Reagan was right: We are a shining city on a hill. But that we is not America. We are believers, followers of Jesus, pointing people toward the cross. Only there will we find the good we so desperately pursue. We can use our votes and voices to nudge our temporal government toward justice, but those are crude means. The glorious ends we seek require God and the transformation only he can provide. Our politics should not be devoted to restoring Christendom but to revealing Christ.

Mark Caleb Smith serves as professor of political science and director of the Center for Political Studies at Cedarville University and is the author of numerous articles, book chapters, and other publications in religion and American politics.

Emma Blakemore is a fellow at the Center for Political Studies at Cedarville University. She earned her undergraduate degree in international studies from Cedarville, and in her role at the Center, she focuses on research initiatives in law, religion, and politics.