A few years ago, a widow approached a church in Uganda to ask for help. After discussing her situation, the church council recommended they give her food. The pastor, however, encouraged the leaders to first find out about her family situation.

After speaking with her relatives, the council discovered that her children were well off, but refused to take care of the widow because of a family argument. So the pastor organized a reconciliation meeting. The children forgave their mother and decided to take care of her again.

If the church had rushed in to help without considering her family’s responsibility, the widow may have kept coming back to the church for ongoing support, and the family may never have been at peace.

As a missionary in Uganda, stories like this have deeply influenced my approach to helping those in need around me. I often struggle with these questions: “With requests for money coming every day, who should I give money to? When is it okay to say no?”

One obvious guiding priority is to give financially where there is the most need. To this, we all agree. But our world is increasingly interconnected. I can simply click a button to give financially to help people almost anywhere. If the only guiding principle is the need, I would get stuck in the paralysis of indecision.

But Scripture takes me beyond simply looking at the greatest needs to also seeing that God has given me greater responsibilities to help certain people. I propose looking at financial giving through a concept I call “circles of priority.” That is, when it comes to financial generosity, I should prioritize the people and communities closest to me.

I believe the New Testament reveals that my first concern should be to take care of my family or those I am relationally close to. As Paul writes in 1 Timothy 5:8, “Anyone who does not provide for their relatives, and especially for their own household, has denied the faith and is worse than an unbeliever.”

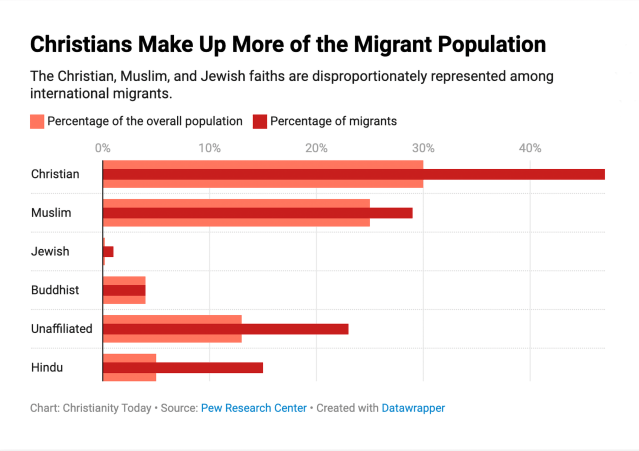

Graph by Christianity Today

Graph by Christianity TodayNext, in Galatians 6:10, I learn that I am also to prioritize those who I am spiritually close to. Here, Paul writes, “Therefore, as we have opportunity, let us do good to all people, especially to those who belong to the family of believers,” affirming that, while I need to love all people, I have a special responsibility to help my brothers and sisters in Christ.

Finally, consider the parable of the Good Samaritan in Luke 10:25–37. In this passage, three individuals see a man beaten up on the side of the road. The surprise is that the priest and the Levite do not stop to help, but the Samaritan does. Loving my neighbor does not mean loving only those people who are like me. The Samaritan is doing exactly what all people should do, helping the person he sees physically suffering right in front of him. Thus, there is also a priority of caring for people I am geographically proximate to, people I meet in my day-to-day life.

All Christians around the world should prioritize helping those relationally, spiritually, or geographically close to them, in addition to the clear priority of helping those with the greatest needs.

We have less responsibility the farther out the circles go. But as we have time and resources, we can, and indeed must, try to help people on the outer circles as well. For example, in the New Testament, Paul urges the churches to voluntarily raise money for the needy Christians far away in Jerusalem (1 Cor. 16:1-4).

The circles of priority have guided me to prioritize helping our friends, neighbors, and our local church while still occasionally helping people with dire needs far away from Uganda through giving to international organizations. This strategy has relieved me of a great burden. I am not tormented by guilt over the other 47 million Ugandans I am not helping. I am not God. I do not have unlimited resources or time. Rather, I can help with joy and generosity, knowing that God uses each one of us in small ways to together make a big impact.

For instance, when a person I have never met calls and says, “Pastor, please, I need you to pay for my children’s school fees,” I usually say no, because of my limitations. Per the circles of priority principles, I want to prioritize giving in the context of close relationship, which allows me to understand the person’s real needs and so I can walk with them over a long period of time, giving periodically and encouraging them as they make changes. This doesn’t stop me from giving money to organizations working with the poor, because many organizations also prioritize long-term relationships.

The circles also guide church ministry. Take the example of Covenant Reformed Church in Soroti, Uganda. This church receives about $3 a week in offerings and about $1 a week for their charity basket, which they use to help materially poor people in their church or people with disabilities. This church shouldn’t feel guilty that they are not helping orphans in other countries. God is using them to care for the people close to them.

A wealthy American church can probably help people in their own church while also financially supporting organizations who help the poor overseas. At the same time, this principle can also correct a church that has become focused only on giving to people in other countries while largely ignoring materially poor people who live in the same city or people struggling in their own congregation.

Following the circles does not take away all hard decision-making. Sometimes I will need to refrain from addressing lesser needs in my own family or community in order to help people far away in life-and-death situations. It takes wisdom to discern when a great need trumps relational, spiritual, or geographical proximity.

In following the circles of priority, care should be taken not to abuse them. It is easy for affluent Christians to justify to ourselves that we are doing enough because we are focusing on caring for the needs of our inner circles—our families, our local church, and our community. But remember, Jesus said in Luke 12:48, “From everyone who has been given much, much will be demanded.” For those of us from exorbitantly rich nations, we are more than able to give generously to help those in extreme poverty around the world while also taking care of people in our inner circles.

It’s also possible for affluent Christians to abuse the circles by controlling who is allowed to be in our inner circles. For instance, we can move to upscale neighborhoods where we won’t end up bumping into materially poor neighbors or take driving routes to work that will bypass where people are begging. We can choose to attend a local church that is full of materially rich Christians who make us feel comfortable in our wealth. Many of us wealthier Christians should consider how we can bring materially poor people into our closer circles, or how we can more intentionally choose which community we will live in and which church we will belong to.

The circles of priority not only guide us in discerning who to help but how. I should offer assistance in a way that will not destroy the responsibility, stewardship, or generosity of others. I should step in and offer help when the person in need is not able to be helped adequately by his or her closest circles. This is what the Ugandan pastor did in finding out first if the widow’s family was willing to care for her.

In a similar way, this principle also applies to the ministries of churches and organizations as they strive to alleviate poverty. They must consider the circles of the individual or community they want to help.

In Eastern Uganda, people from the Karamoja region used to violently raid and steal cattle from the Iteso tribe. Thankfully, peace was finally achieved after many years of government and church initiatives. Soon after, there was a famine in Karamoja. Some of the Iteso churches worked together to bring a truckload of food to Karamoja to show their forgiveness and love.

However, when they arrived, they were shocked to discover that the United States had already sent many tons of relief food. The local Ugandan church’s efforts became redundant and unnecessary, leaving these Christians incredibly disheartened.

While the Americans may have genuinely intended to help, they did not consider what the people closest to the area might have been able to do first. They unintentionally stole the blessing of giving from the Ugandan church and undermined this opportunity for furthering reconciliation between the two tribes.

Organizations should be careful to allow the circles that are closest to the individual or community that needs help to be the first ones to help. Most of the time, the people closest to the situation are the ones who know the most about which interventions will be appropriate. But an additional benefit of promoting the responsibility of a person’s closer circles is the improved capacity and stewardship of institutions in these circles—families, churches, schools, local organizations, and government structures. This will produce long-lasting impact in a community.

In my observation as a missionary working in Africa, ignoring this principle is one of the most common mistakes that churches and international organizations make. The result is dependency.

For example, consider how some organizations may rush to create an orphanage in a community without first considering whether or not the orphans’ relatives may be able to adopt the children and care for them with additional financial support. Or consider child sponsorship programs in which children have their school fees completely covered, in addition to receiving gifts like clothing or toothpaste. The result is that it is not uncommon in Uganda to hear parents come to an organization sponsoring their child and say, “Your child is sick, you need to treat your child.”

Instead, help should be given in a way that will enrich the parents’ responsibility of sending their own children to school. It would be better to help the parents improve their jobs and income earnings so that they can pay the fees themselves—or to first find out what little the parents are able to pay, in what way their local churches are also willing to help, and then to supplement their efforts. If this process results in the organization giving less money to each family, then they can use the extra funds to support an even greater number of families in even more communities. It’s not about giving or helping less. It’s about practicing wisdom in our generosity.

Before helping an individual or community, always begin by listening. What is the local government doing to respond to the need? Are other churches looking to offer help to the same people? Build upon the efforts of local institutions by partnering with them, rather than replacing them in their God-given roles. There is joy and blessing in giving; we should not keep all the blessing to ourselves!

To close, reflect on this story out of Niger. In 2010, nearly half of the population of the West African country struggled with food insecurity. An international Christian organization donated grain and worked with a local Christian group to sell that grain to people in need in several communities at a discounted price.

In the past, the international organization had provided grain to individuals with disabilities or chronic illnesses. But this time, the international staff challenged the local group to consider raising funds locally from their own churches to purchase the grain that would then be distributed freely.

At first, the group members were skeptical, not imagining that there was anything the poor churches could do on their own to help others. But the churches gave generously and were able to purchase grain for 98 people who had the most need in those communities. In the end, the local group thanked the organization for encouraging their churches to participate in the giving.

“It was such a privilege to help, to know that we weren’t just distributing somebody else’s gift but it was from our own pockets and from our own hearts,” said one community member. “Everyone in the village knew that it came from us.”

Anthony Sytsma works for Resonate Global Mission in Uganda, where he mentors and teaches pastors and facilitates Helping Without Hurting in Africa.