To the dutiful Bible reader, Chronicles might seem a bit baffling. As we read, we might find ourselves wondering, Haven’t I read this before? The short answer is yes and no .

The books of 1 and 2 Chronicles retell some of the same stories of Israel and Judah that appear in the books of Samuel and Kings. But the chronicler also offers a fresh perspective on those years by incorporating new material and leaving other stories aside. His decision about what to keep and what to add is not arbitrary but intentional. And if we’re paying attention, we will find that the chronicler has a distinct message that we can learn from today.

First, only 50 percent of Chronicles is repeated material from Samuel and Kings. On the one hand, that’s a lot of overlap. But on the other, that also means that half of Chronicles is brand new material. Which means we cannot afford to overlook it!

And while the content of Chronicles overlaps with previous material, it emerged over 100 years later—giving the chronicler the benefit of hindsight and the opportunity to address a new set of challenges for his generation. The people of Judah had just returned from exile and were facing the massive task of rebuilding the temple of Yahweh in Jerusalem, which King Nebuchadnezzar had destroyed. This task profoundly shapes the backdrop to the books of Chronicles.

If you set Chronicles side-by-side with Samuel and Kings, you’ll find that the new material focuses on two primary topics: David and the temple. The chronicler spends extra time on the genealogy of David’s family and the details of David’s legacy. And although Kings focuses on the northern kingdom of Israel, Chronicles highlights the southern kingdom of Judah, where David’s descendants reigned.

Likewise, the chronicler adds bonus content about the temple. We read about David’s preparation of building materials and more details about Solomon’s building process and dedication. The chronicler also tells us about five distinct temple renovation projects spanning hundreds of years. We hear the prayers of various kings at the temple and find out which of the Levites is assigned to which temple-related tasks.

These two important themes—David and the temple—are evident from the beginning of the book in the genealogies listed. Now, it’s understandable to feel like skimming the nine chapters of genealogy that open the book. But if you do, you may miss out on significant clues about what details matter to the chronicler and why.

Despite their length, the genealogies do not offer an even-handed and exhaustive account of all 12 tribes of Israel. Rather, they focus especially on (you guessed it!) the family of David and the tribe of Levi, since their descendants were the ones primarily called to serve in the temple.

Another thing you might notice if you compare Chronicles to Samuel and Kings is that the chronicler leaves out most of the unflattering stories about David.

In Chronicles, David doesn’t take advantage of Bathsheba, nor does he lose his grip on his sons. It’s not that the chronicler is unaware of David’s failures; clearly, he has Samuel in front of him as he writes, since so many stories are taken from it verbatim. But, for the most part, the stories of David’s struggles simply don’t advance the chronicler’s purpose—with one exception. Since it’s the exception that proves the rule, let’s take a closer look at it.

Given the otherwise squeaky clean portrait of David in Chronicles, it’s surprising that the chronicler includes the story of David’s ill-advised census, when he ordered his commander to register their fighting men. His failure to trust God’s protection resulted in disastrous consequences for the nation.

To understand why this story appears in 1 Chronicles 21, we must pay close attention to the consequences for David’s actions. David had called for a military census against the advice of his commander, Joab. The exercise was both a flex of David’s power and a failure of trust in God’s protection. But soon after the numbers came in, David realized he had sinned and prayed for forgiveness.

In response, God allowed David to choose his own consequence from three options: “three years of famine, three months of being swept away before your enemies … or three days of the sword of the Lord—days of plague in the land, with the angel of the Lord ravaging every part of Israel” (1 Chron. 21:12). David chose the last option, deciding to put himself and the kingdom into God’s hands.

The plague was indeed devastating, with many unnecessary deaths due to David’s folly. But amid the judgment, Yahweh showed compassion on the nation by stopping his angel from destroying more people—in a moment strikingly like the one on Mount Moriah, when Abraham was about to kill his son Isaac and the Lord called for him to stop (Gen. 22:9–14). The narrator also tells us exactly where the angel of the Lord was when the plague stopped in its tracks— “standing at the threshing floor of Araunah the Jebusite” (1 Chron. 21:15).

This location is of paramount importance to the overall plot of the book. The threshing floor was where people would process their grain harvests by dragging heavy equipment over the stalks of wheat to separate the grain from the straw. When possible, they carried out this work on hilltops so the wind could blow away the chaff, leaving only the nutrient-rich grain behind.

So, David bought this prime hilltop threshing floor from the Jebusite, building an altar there to offer burnt offerings and fellowship offerings, to restore fellowship with Yahweh and thank him for his mercy. Remarkably, “the Lord answered him with fire from heaven on the altar of burnt offering” (1 Chron. 21:26)—a dramatic response echoing the time the tabernacle was built (Lev. 9:24). David logically concluded that this would be the perfect place to build the temple, saying, “The house of the Lord God is to be here, and also the altar of burnt offering for Israel” (1 Chron. 22:1). But, as you might remember, it was not David but his son who would take up this task.

The chronicler eventually draws these threads together in a dramatic flourish in 2 Chronicles: “Then Solomon began to build the temple of the Lord in Jerusalem on Mount Moriah, where the Lord had appeared to his father David. It was on the threshing floor of Araunah the Jebusite, the place provided by David” (3:1)—where God showed mercy to David by sparing the Israelites and the very spot where God likewise spared Isaac. The chronicler doesn’t want us to miss this!

Why tell this unflattering story about David in a book that offers an otherwise positive picture of him? The census debacle is essential because it ultimately leads to establishing the location of Solomon’s temple, which is the other key theme of the book. In this very place, God showed mercy to the Israelites and provided dramatic evidence of his presence and blessing.

The chronicler wanted to underscore for his own generation the importance of rebuilding the temple and regathering those called to serve in it, who were just starting over after returning to the land. They desperately needed a sense of continuity with the past and some reassurance that God’s presence would grace their community once again. And if we skip over the books of Chronicles, assuming they’re on “repeat,” we may miss God’s call to our own generation to prioritize temple-building.

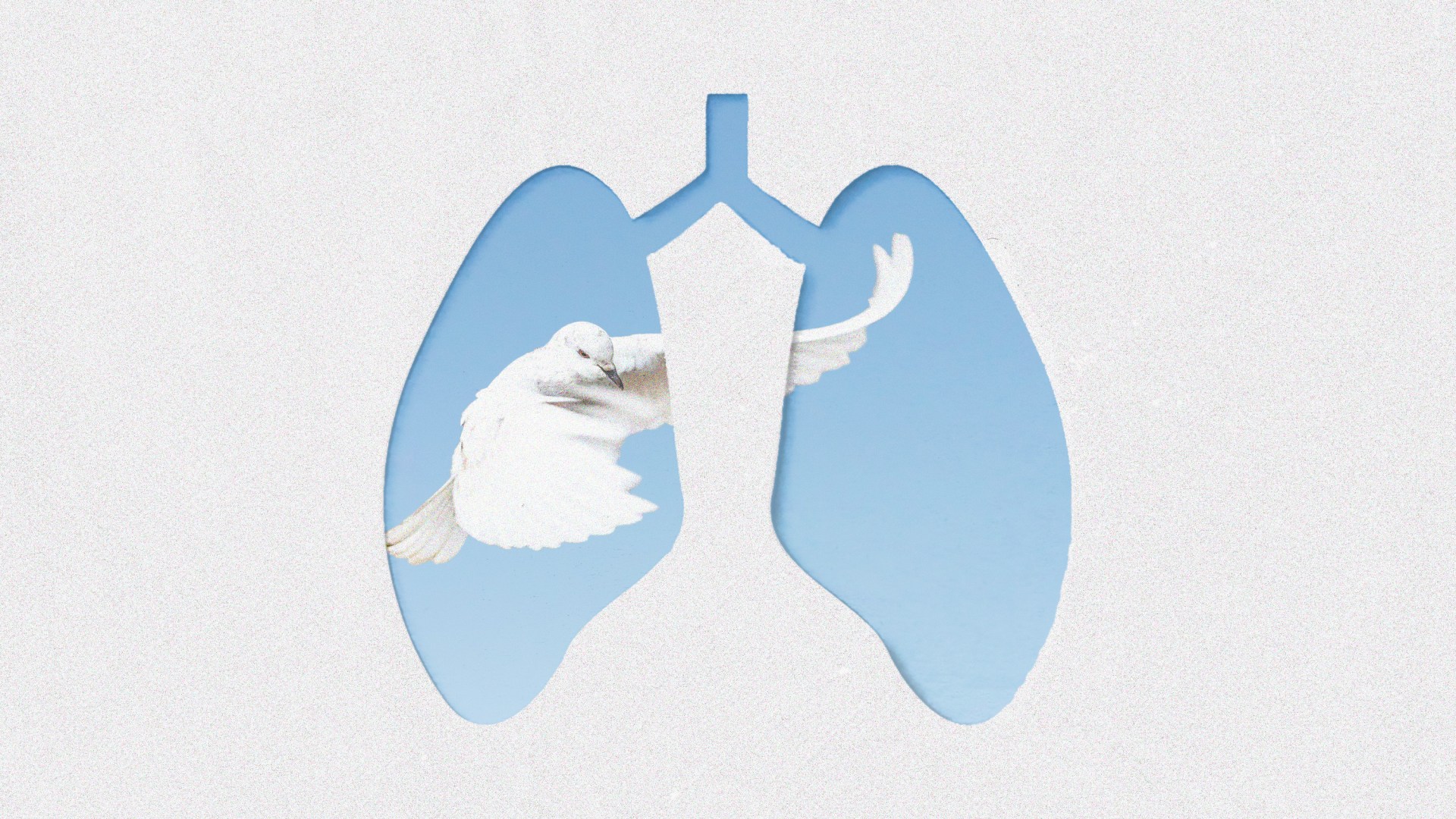

We face a similar task today: How can the church rebuild after a global pandemic? How can we be restored after so many public scandals and deep divisions? Yet our generation’s task is not to rebuild a physical temple but to lean into our collective identity as the body of Christ. Especially in the West, where expressive individualism is so valued, the book of Chronicles offers a much-needed corrective. It’s not about me, it’s about the people of God doing the work of God in the world. And by underscoring our shared mission, we can rediscover our sense of purpose.

“Consequently, you are no longer foreigners and strangers, but fellow citizens with God’s people and also members of his household, built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the chief cornerstone,” wrote the apostle Paul. “In him the whole building is joined together and rises to become a holy temple in the Lord. And in him you too are being built together to become a dwelling in which God lives by his Spirit” (Eph. 2:19–22).

This is not a solo project. As Paul and Sosthenes say elsewhere, “Don’t you know that you yourselves are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in your midst?” (1 Cor. 3:16). The yous here are all plural: “Don’t y’all know that y’all are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in the midst of all y’all?” No one goes on an architectural tour to admire a single brick, but instead to stand in awe of buildings made up of hundreds of thousands of well-placed bricks.

For us today, temple-building involves meeting together regularly, seeking God together, learning to love one another well, and discovering how to honor God together in our generation. No individual can demonstrate the fullness of God’s glory to a watching world alone. Rebuilding God’s house is a group project—and we all need each other.

Carmen Joy Imes is associate professor of Old Testament at Biola University and author of Bearing God’s Name and Being God’s Image. She’s currently writing her next book, Becoming God’s Family: Why the Church Still Matters.