The Minister Looks At The Pew

Mixed feelings possess the minister in his appraisal of the pew, the source of his joy and distress. The virtues and excellencies of the congregation sustain his spirit; the defects and imperfections weigh down his soul. The pew displays the paradoxes of loyalty and indifference, knowledge and ignorance, humbleness and pride, generosity and covetousness, warmth and coldness, sincerity and hypocrisy, good and evil. The spiritual and the natural are both in evidence.

Surely one of the gratifying virtues in the life of a congregation is loyalty. Whether the church is at peace or beset with troubles, whether the church is prosperous or destitute, a band of devoted members exhibits resolute loyalty. Difficult situations beset the life of almost every congregation but are overcome by the steadfast and the unmovable. The minister, too, benefits from this virtue. Whether his gifts be many or few, whether his sermons be worthy of praise or blame, loyal support rejoices his heart.

Of inestimable value to church and minister is the inner circle of spiritual Christians found in every congregation. They hunger and thirst for the Word; they hold up the ministry in prayer; they serve generously with their tithes and time. Appreciative, not critical, tolerant—they form an oasis in what sometimes seems a barren land.

In spite of the presence of those who hunger for the Word, a shock early in the ministerial life is the awakening realization that the majority in the pew have no desire for a deeper knowledge of the Scriptures. Even some of the soundest evangelical congregations have little appetite for the meat of the Gospel. Nor may the preacher presuppose any diligent study on the part of the pew in preparation for the message. He must make the message light and airy to sustain interest. He knows that nominal Christians prefer vague generalities, enhanced by the eloquence of Athens, and have no taste for the soul-searching truths of Jerusalem.

Piety displays itself in many varieties before the eyes of the pastor. He beholds that ceremonial and ritual piety which does not go beyond the outward rites of the Church. He perceives with sadness that sabbatical piety which limits religion to the first day of the week. He views with alarm that negative piety which consists only of a series he observes the “holier than thou” piety which refuses to mingle with publicans and sinners. He deplores the noisy piety that glories only in the ostentatious and vain-glorious display of statistics and visible results.

In striking contrast to pseudo-piety, the minister discovers a proper piety that constantly grows in the grace and knowledge of Jesus Christ. He perceives that those who grow spiritually are those who cultivate the means of grace. Humbleness and consciousness of imperfection distinguish them from the proud and self-righteous. They bear injuries and provocation with meekness. Fruits of the Spirit become increasingly evident in their lives. Charity toward others is more than sounding brass or a tinkling cymbal. They sincerely seek to give pre-eminence to Christ. For this genuine piety the minister praises God.

To his distress, the minister discovers that the loyalty of the pew often consists in a loyalty to the local church only. Local programs find warm-hearted support whereas the world-wide program of evangelization, initiated and commanded by the Head of the Church, finds only cold-hearted indifference. Indeed, if his efforts to inspire a world-wide vision are constantly defeated, the flaming ardor of the undershepherd is in danger of being quenched by the coldness of the flock.

Puzzling is the pew’s attitude that the battle for souls and the fight against evil should be waged by the minister alone. The notion prevails that the preacher alone must draw the sinner into the church and cleanse the community of evils. Military battles are not fought by the officers alone. Yet the battle against evil is a thousand times more important and difficult. Christ gave no statement, “the ministry is the salt of the earth.” Nor did He command, “Go ye, clergy, and make disciples of all nations.” Yet that is the prevailing impression on the part of the pew.

The pulpit must constantly guard against those who would secularize the Church by changing it into a social club. The pew may be motivated by a desire to attract the ungodly into the church. “See,” they say in effect, “we are not so narrow or unworldly as reputed. We have the same pleasures you enjoy.” However, the minister knows that the way for Christians to attract the unchurched is not by aping their pleasures but by proving that the Christians’ pleasures are infinitely superior. The Church should be known as the source of spiritual comforts and pleasures for which many in the world hunger and thirst. Would that the passion of the pew were to make the world spiritual rather than the church worldly!

Embarrassing to the minister are questions pertaining to stipend. He takes heart, however, in observing that even the secular press is sounding the alarm about the inadequate compensation of ministers. “The noblest profession of them all” is the estimation often heard, but the insincerity of that phrase on the lips of some is seen in their modest reimbursement of the “noblest,” in contrast with their compensation of other professional men, for instance, the lawyer or physician. Perhaps such reluctant supporters regard estates and bodies of greater value than souls. A Puritan divine made the telling comment that pastors should have tithes that they may have a fellow feeling of the people’s loss, and a fellow comfort in their increases. The Lord made adequate provision for the priest of the old dispensation; the church should do likewise for the minister of the new.

The empty pew, alas, cannot be overlooked. It confronts the vision of the minister constantly. It is a silent yet expressive witness of a preference for the radio and television above the pulpit. It attests to the increasing number of Sunday leaves of absence. The empty pew becomes vocal only at Easter and Christmas—with groans caused by unaccustomed loads. Like a tombstone the empty pew gives cemeterial atmosphere to the church. It witnesses of the dead.

Bitterness, wrath, envyings, strife, faction, and divisions pervade the church in the twentieth century as well as in the first century. These sins are engendered often by the union of petty spirits with small-mindedness. Until the world can say “How these Christians love one another” instead of “How these Christians dislike one another,” Christianity can make no deep impact on the life of the world. Jerome records the tradition that when the apostle John was old and feeble, he was carried by young men to the meetings. He could no longer say much, but he repeated the words, “Little children, love one another.” When asked why he constantly repeated the same words, he would reply, “Because this is the command of the Lord, and because enough is done if but this one thing be done.”

Would that the evaluation of the twentieth-century church were written by Him whose “eyes were as a flame of fire.” He would write of the labor, of the patience, of the zeal, of the tribulation, of the faithfulness, and of the charity evidenced in the life of the membership. Also He would write of the abatement of first love, of the avarice of modern Balaams, of the toleration of heresy, of the decline of good works, of the submission to seductive Jezebels, of the deadness, of the lukewarmness, and of the miserable poverty of those rich in material goods but poor in spirit.

A Layman Looks At The Pulpit

That the pew should look and listen to the pulpit with an appraising eye and an evaluating ear is only proper. What minister would desire an audience so docile and wooden as to take stolidly all that might be preached without a critical analysis of the message? At Berea, the Apostle Paul was stimulated by hearers who searched the Scriptures daily to see whether he was preaching the truth. An enlarged number of spiritual descendants of those Berean Christians would prove a blessing to both pew and pulpit.

It is Sunday morning and we sit in the sanctuary, quietly and restfully. The setting is of minor importance. Whether severe in simplicity or cathedrallike in beauty, no aesthetic or worshipful atmosphere can, of itself, supply the spiritual needs of mankind.

Who is sitting in the pews? Men and women, a cross section of the complex and cosmopolitan world of which we are a part. Some are in financial straits; others more fortunate. Some have social and educational advantages; others lack both. Here may be people with skin of varying color. None of these differences is of eternal import, for only two kinds of people occupy the pews this morning: those who have a saving relationship with Jesus Christ, and those who have not.

But can our complicated lives be so easily catalogued? Do not men and women have multiplied problems? Do not Christians represent varied stages of development in Christian faith and living? Do not these obvious variants in experience demand from the pulpit an erudite and all-encompassing concept of the Christian ministry and its message?

There are some in the pew today who feel that preaching has tended to complicate rather than to simplify the Gospel message. By dealing so much with the fringe results of sin in disordered lives, it has obscured the basic need of every human heart. Some hearers would call this an attempt to treat symptoms rather than the disease that causes the symptoms.

The layman needs biblical teaching, and the average layman wants it. He needs a dynamic for daily living, not simply an ethic a little loftier than his own highest aspirations. He needs as much to be told where he can get the power to do the thing he knows to be right, as to be told what to do.

Looking over the Sunday morning congregation, made up of only two kinds of people, the redeemed and the unredeemed, we are moved to reflection. Are not hundreds of sermons wasted, at least in part, because they are instructing non-Christians how to act like Christians?

Admittedly, to insist that all sermons be directed to those in need of conversion would be foolishness. Much of the minister’s work must, of necessity, center in developing Christians in their knowledge of Christian truth and in living as Christians should. But many a layman, as he thinks back to his own admission into church membership, knows that there was no conversion experience with Christ. In fact, it is only too likely that he responded to an impersonal invitation to “join the church,” nothing more.

Now, sitting quietly in the pew, what is the message he hears? What is the content of that message? What is the basis for the sermon? Whence comes its authoritative note, if any? Some who listen may be impressed by oratory, by impeccable pulpit manners, by obvious scholarship, by a clear familiarity with world affairs. But the average member of any congregation has a soul hunger for spiritual bread, that not even a glittering homiletical stone can satisfy.

It is axiomatic, and should not need emphasis, that human wisdom can never compensate for divine truths. When preaching is saturated with and centered in the simple affirmations of the Scriptures, carrying with them an authority, a power, and a transforming quality, men’s souls are fed. When this sacred source of wisdom is ignored, people go away hungry.

Preaching takes many forms, topical, doctrinal, expository, and so forth; all are needed. But preaching is real only when centered in the divine revelation that is the Word of God. Paul called Scripture the sword of the Spirit. It is still quick and powerful; it still convicts and convinces; it still lays bare the inmost secrets of the human heart; it still shows man both how to live and also how to die and live forever.

The pew serves no good purpose when it contributes to an excessive sense either of ministerial insecurity or of security. Some occupants of the pew criticize their pastor, no matter how well he preaches or how faithfully he serves them. Others would gush over the preacher if he got up and repeated a nursery rhyme in a pleasing tone with soft modulation.

Over against these two extremes is that great majority who sit and take whatever is given them, either rejoicing or suffering in silence. The consecrated layman, however, belongs neither in the scorner’s seat, nor in the gulley of the gushers, nor in the valley of affliction.

The layman has a right to expect certain things from the pulpit. We would suggest five.

Simplicity. The man in the pew is not trained technically in theological terms, nor should this be necessary. Even the most profound doctrines can be presented so that the layman can understand them. The simplicity of the Gospel message should never be forgotten.

Authority. The Christian message has a basis in authority, the authority of the Scriptures in which God has spoken by the Holy Spirit. Without such authority, something is lacking, and the pew is easily affected by the deficiency. The preacher needs the authority derived from God Himself and His revealed truth if he would speak to the hearts and lives of other men. The biblically based “Thus saith the Lord” still impresses the hearer more than the profoundest opinions of men.

Power. Power in preaching depends on the presence of the Holy Spirit, both in the preparation and in the delivery of the sermon. For such power—and in human terms it is something both intangible and inexplicable—there is no substitute. Human wisdom, oratorical flights, literary style, personal opinions, all will soon be forgotten. God’s presence in a sermon is imparted to its hearers and carried away in the heart. On such power from the Holy Spirit rests the hope for a repetition of the experience of the men on the Emmaus road: “Did not our hearts burn within us, while he talked with us by the way, and while he opened to us the Scriptures?”

Urgency. This urgency is not one of a possibly imminent world cataclysm. Nor is it an urgency having to do with physical, economic, or social wellbeing, important as these may be. The Christian ethic, as a matter of personal faith in the Lord Jesus Christ and as a way of life, is the most important decision with which man can be confronted. Until the issue between God and man is settled aright there can be no right solution of man’s problems with man. Jesus expressed the urgency of His own mission to this world in the arresting phrase “should not perish, but have everlasting life.” “Perishing” is a desperately serious matter, and finding the way to prevent it is certainly a matter of the greatest urgency. The second phase of the Christian faith—how to live as a Christian—is also a matter of urgency. In both matters the pew needs to capture this sense of urgency from the message of the pulpit.

Decision. A good salesman works for a decision. A good agent for Jesus Christ does the same. We laymen need to face up to the universal need for such a decision. Only too often we find ourselves confronted with an invitation to “join the church.” Such a step is a vitally important matter, but man’s first decision has to do with the acceptance of Jesus Christ—WhoHe is and what He did. Many of the problems in individual lives, and in the church, stem from the fact that only too often such a decision has never been made. There are many subsequent decisions the Christian must make; in fact, they must be made daily. When Christianity becomes a vital reality to the individual, such decisions inevitably follow.

Finally, the pew should look at the pulpit through eyes and from a heart that has prayed for the one standing there as a messenger of God. In a true sense, he stands as a dying man preaching to dying men. He needs and deserves the sympathetic understanding and prayerful support of those to whom he ministers.

The Church moves forward as pew and pulpit unite in one common faith and purpose: to know Christ and to make Him known.

***

The Christian And Political Responsibility

Differing from any other in the world, the American political scene reaches heights of asininity and of greatness, of fiction and fact, which can easily confound even the most astute.

Despite the defects of political controversy, every American should be thankful that, by and large, the charges and counter charges of political campaigns are projectiles of hot air, not lead, and should glory in the fact that he can vote.

In such an atmosphere Christians, along with all others, can be carried away easily by personalities, emotion, and distortion. In the face of these campaign pressures we need the sobering effect of clear judgment, a judgment possible only by looking at candidates and policies with Christian objectivity.

An increasing number of individuals refuse blindly to follow the dictates of a particular party. This is a wholesome trend. There is always a danger, even in a republic, of unwittingly absorbing the totalitarian philosophy of letting someone else do one’s thinking.

It should be axiomatic that a Christian should be a good citizen. Unfortunately, such is not always the case. One outstanding Christian recently metaphorically threw up his hands in disgust: “Why vote? There are but two alternatives—creeping socialism under different labels.” No doubt there is the danger that a large vote enables each party to claim a mandate from the people for compromise measures. But, in a democracy, where free speech is accorded each citizen, and where all can vote according to the dictates of their own wills, the government one ultimately lives under is the government of his own making or neglect.

Other Christians, with a wistful idealism, see the world through the thick lenses of an earth-bound pessimism. Because no particular candidate meets their idealistic concept, they may be inclined to stay away from the polls and in so doing, their idealism is dissipated into the thin air of wishful thinking.

What should a Christian do?

He should exercise his privilege of voting. The secret ballot is a privilege which millions are denied today, and for which many would make any sacrifice.

The Christian should also look both at candidates as individuals and at the policies they espouse. Let him admit realistically that in this world there are no perfect candidates, nor are there perfect governments.

What should the Christian look for? Is the candidate a man of moral rectitude? Does he look upon his office as deriving its authority from God, and his personal life and administrative acts as under constant divine scrutiny? In other words, a Christian should vote for the man who, in his judgment, will exercise, directly and indirectly, the greatest influence for righteousness at home and abroad.

A Christian should also evaluate the men by whom a candidate surrounds himself, again looking for moral principles and personal rectitude.

Furthermore, a Christian citizen should look at the policies espoused by a candidate and a party. Personal and group and sectional admission to the “federal feed trough” is an incentive for political affiliation which strikes the nadir of selfishness. The national good must take priority over personal and sectional advantage.

Finally, the Christian citizen owes it to himself and to his country to pray for divine guidance. The one vote cast according to God’s holy will, multiplied many times, is the strength of a democracy. Those ultimately elected are entitled also to the concern and consideration enjoined by the apostle Paul: “1 exhort therefore, that, first of all, supplications, prayers, intercessions, and giving of thanks, be made for all men; for kings and for all that are in authority … For this is good and acceptable in the sight of God our Saviour” (1 Tim. 2:1–3).

Church Membership And Spiritual Ambiguity

For the first time the United States shows a church membership exceeding 100 million. The latest compilation of the National Council of Churches’ Yearbook of American Churches discloses that the trend begun during World War II is continuing; church membership gains are outstripping population gains. Last year church membership increased 2.8%, population 1.8%. The total figure, 100,162,529, includes 58,448,000 Protestants and 33,369,000 Roman Catholics.

Does this fact that there are more people in the churches, and more professing Christians, signify the spiritual revival of the nation? Surely the United States today is the lifeline of much of the world’s evangelism and missionary effort. And there have been heartening evidences of new evangelical earnestness.

But it would be too much to say that the soul of the nation has undergone repentance and revival. The minister who said that “the world at its worst needs the Church at its best” did not understate the demands posed by our decade. What prospect is there, one university professor in the South has asked, that Christians will grow up as fast as the inventors of atomic energy work?

We need a demonstration of Christian superiority which is culture-wide, a display of the lordship of Christ which extends to every sphere of life on each day of the week. The early Christians were bent on a maximum experience. Their Christianity not only began at the altar of regeneration and repentance, but it did not end with formal church membership. Their mood was not simply receptive, but appropriative and productive. They were dedicated to an obedience to the risen Lord’s commands, not to a mere conformity to the best standards of society. The cross was for them something to live with and by, as well as something to live under. That is why they gave their contemporaries a demonstration of Christianity superior in awesomeness to any of the moral resources paganism could command.

The Tenuous Prospect Of World Peace

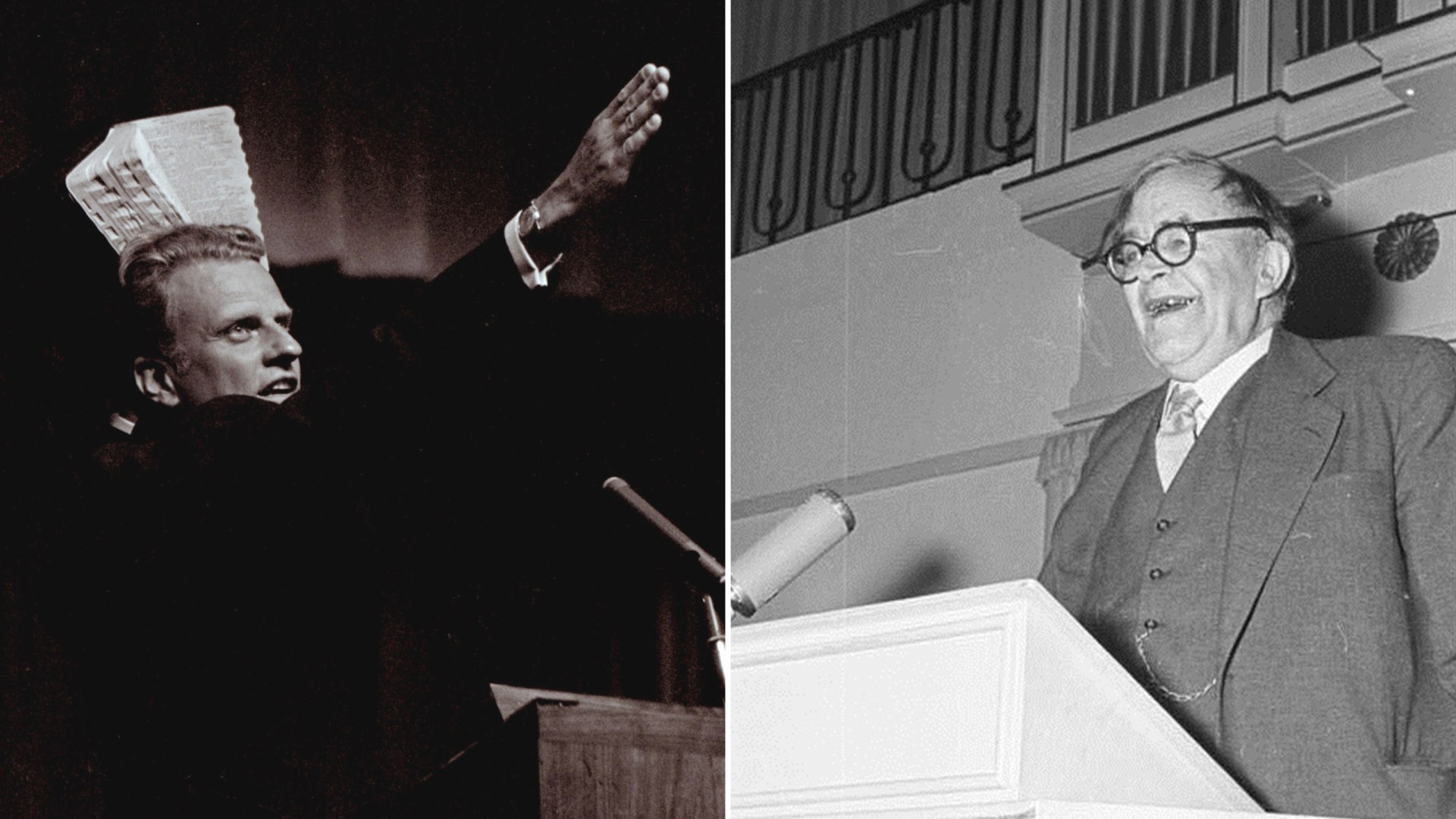

To a generation bristling with hope for world peace, the article by Lieutenant General William K. Harrison may seem like “a counsel of pessimism and despair.”

But it calls for sober reading, even by those who do not share in detail the distinguished general’s eschatological views. CHRISTIANITY TODAY, in the course of time, will present representative views of the way in which the climax of history is anticipated by evangelical Christians sincere in their differences. But the present article confronts us with a significant judgment upon the past and the present no less than upon the future.

General Harrison is one of the senior generals of the United States Army, and served as United Nations truce delegate at Panmunjom. In those tedious transactions with the Communist generals in Korea, he carried in his own heart an anguished world’s hope for the end of armed conflict.

That the general does not share the opinion, widespread even in ecclesiastical circles today, that the United Nations (or any other organization) is the world’s best hope for peace, is significant enough. That he should find that hope in Jesus Christ alone is a refreshing reflection of the biblical emphasis that peace, in national as in individual life, is the gift of God. This conviction may not be popular, especially in a generation whose hopes are sociological and anthropological, rather than theological, but that is all the more reason it needs to be voiced.

Solomon’s trust in horses, and ancient Israel’s trust in alliance with Egypt, may differ from the modern confidence in the atomic bomb and in the United Nations, but the difference is only one of degree, and not of kind. The common factor in both is the neglect of the Living God as the final arbiter of the destiny of nations and of the fortunes of war and peace.

Back To The Bottle The Day After Christmas

The editors of Life published a special “Christianity” issue a year ago. In many respects, the issue was one of the finest of its kind in contemporary journalism. Among its virtues was the absence, at this otherwise lucrative season for such commercials, of liquor advertising.

Like much of the religious interest in America, this sentimentality at Christmas has a sequel. A survey of fifteen leading publications shows that, during the six months January–June, 1956, Life carried more pages of liquor advertising than any of its competitors with the exception of one. During that period the New Yorker carried 221.81 pages, Life 127.80, Time 90.60, Newsweek 89.06, Esquire 79.26, Cue 75.31, Collier’s 68.50, U.S. News and World Report 59.25, Look 51.00, Ebony 50.64; Sports Illustrated 44.98, Holiday 42.91.

There is little virtue in putting Christ back into Christmas if He is ejected the morning after. That is like filling Santa’s pack bag with spirits made in Kentucky, and smuggling them in under the cover of the night.

Reformation Day And Protestant Tradition

The theme adopted by the National Council of Churches for the observance of Reformation Sunday, October 28, is “the continuity of the Christian Church in the Protestant tradition.” What a strategic opportunity to present three great Reformation principles unacceptable to the Roman Catholic Church: (1) Holy Scriptures as the sole normal authority for faith and life, (2) Justification by faith alone without any merits of good works, (3) the priesthood of all believers. The Protestant tradition bases doctrine and religious life entirely on the Scriptures.