The needle moves quickly, back and forth and back again, making a pattern I find almost intelligible. It’s an Instagram video in the genre that has come to fascinate me: repairs. Similar clips show rougher work—a stonemason restoring a 900-year-old cathedral, a handyman reviving a neglected home room by room—but in this video, the task is fixing a moth-eaten sweater.

In mere moments, the woolen looks good as new. The hole has disappeared, the weaving so exactly matched by an unseen mender that I’d take it to be digital trickery had I not watched every stitch.

These repair videos aren’t quite honest, of course. They’re practiced and edited, glossing over the less-than-perfect bits and skipping entirely the discipline and tedium required to master a craft. But they do strike me as a rare case of a message resisting its medium: On a platform that reflects so well our culture’s tendency to seek the newer, more exciting, easier option, repair videos choose the inverse.

Though we see it most obviously in social media, the consumerist tendency against repair is rooted deeply in our culture and institutions. I see that inclination in myself. My children’s socks get holes, and I do not darn them. I throw them away, alongside so many other products made to be disposable or planned for quick consumption and then obsolescence. (This becomes glaringly obvious once you have kids. Of the making of many plastic gizmos there is no end.)

I see this tendency in the tech world in our fascination with artificial intelligence and virtual or augmented reality, especially when they serve as means of escapism. Instead of repairing a real relationship, you can make new friends in the metaverse, friends who’ll never ask to crash on your couch or cry on your shoulder or inconvenience you in any tangible way. Instead of working on your house, you can conjure a dream kitchen using AI. Instead of grappling with some obstacle or inadequacy in the real world, you can retreat into a digital realm where you’ll face no such friction.

In politics, I see this tendency in our apocalypticism and accelerationism. I see it in the rejection of negotiation, cooperation, and compromise in favor of jeremiads about the looming end of our democracy (and not a few calls to hasten its demise).

This isn’t confined to any one political camp. To borrow the broad brush of New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, writing in early 2023, the American left has succeeded in its project of critique to the point of discovering “there isn’t some obvious ground for purpose and solidarity and ultimate meaning once you’ve deconstructed” everything.

Meanwhile, the right likes to talk about repair, about making America great again. But our political right wing is no longer conservative in the literal sense. After its own deconstruction efforts, Douthat argued, it has no idea “how to do a restoration, how to roll back alienation and disaffiliation and atomization.”

Thus we see Robert Kagan at The Washington Post announcing a “Trump dictatorship is increasingly inevitable”; a Trump voter declaring to Politico that he has “no trust” in the American system; and the widespread impulse to destabilize and denounce because so much of our society—in the phrase of a landmark 2022 essay from Tablet editor in chief Alana Newhouse—“is broken beyond repair.”

I see this tendency against repair in the church, too, in a mode of reformation that never moves beyond nailing theses to the door.

Several caveats: First, repair is not stagnation or nostalgia (let alone false nostalgia). It is not necessarily a return to the status quo. Fixing something properly may mean redesigning how it works.

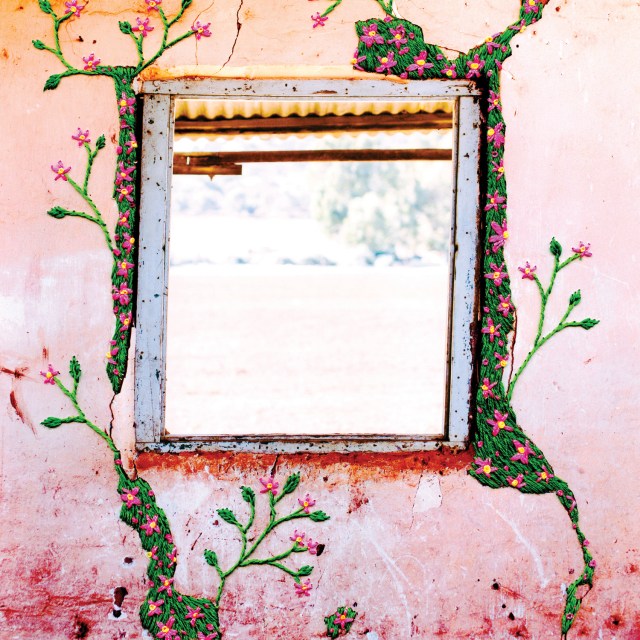

Mending may be visible—an embroidery of flowers over moth-eaten holes instead of a seamless weave. To oppose the tendency against repair is not to reject everything new, prescribe a universal solution, or deny the reality of brokenness. It is rather to have a bias toward the restoration of good things. It is a tendency toward repair over replacement, resolve over resignation, conservation over chaos, staying over leaving, and building up over tearing down.

Motivations underneath this tendency against repair vary widely, and some are far more sensible and sympathetic than others. Sometimes we are merely wasteful or careless—undoubtedly me with the socks. But sometimes we have a true incapacity to repair, born of ignorance or exhaustion or want. Sometimes we seek the fresh, easy thing so as to indulge in distraction or fantasy, and sometimes we reach for newness out of frustration or hope, disgust or righteous anger.

Moreover, repair is not always the right choice. Sometimes things really are broken beyond repair, subjected to the laws of physics, human error or finitude, and the desolation of sin. A marriage can’t be repaired when one spouse won’t repent of abuse. We can’t haul up the Titanic and set it on a second voyage. In Pittsburgh, where I live, the Tree of Life synagogue understandably chose to demolish the building that was the site of the 2018 antisemitic mass shooting. Our Founding Fathers deemed the Articles of Confederation unworkable and replaced them with the US Constitution.

Finally, the line between repairing and replacing or rejecting is not always bright. Sometimes you might replace a part to repair the whole. Sometimes you must debride a wound, cutting away irreparably damaged flesh, before the rest can heal. Sometimes you must deconstruct before you can reconstruct, or doubt before you can believe.

The tendency toward repair is not exclusively Christian, but it deeply resonates with the story of salvation. God has a tendency toward repair.

You can see it in how the earliest Christians spoke of the Atonement, describing God redeeming, reviving, recapitulating, and reconciling us (2 Cor. 5:16–21).

That repetition of the Latin-derived prefix re- is no accident. Each of these ways of explaining Christ’s work in his cross and resurrection has a similar connotation of going back to some lost good: freedom, life, order, love. Each is a kind of repair.

In Isaiah 58, repair is a sign of the restoration of God’s blessing, of the people’s reunion with God after repentance from their sin. The prophet records God saying,

If you do away with the yoke of oppression, with the pointing finger and malicious talk, and if you spend yourselves in behalf of the hungry and satisfy the needs of the oppressed, then your light will rise in the darkness. … The Lord will guide you always … Your people will rebuild the ancient ruins and will raise up the age-old foundations; you will be called Repairer of Broken Walls, Restorer of Streets with

Dwellings. (vv. 9–12)

This theme continues into the New Testament, where Peter preaches that the time is coming “for God to restore everything, as he promised long ago” (Acts 3:21).

Paul writes of creation being “subjected to frustration,” waiting to “be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the freedom and glory of the children of God” (Rom. 8:20–21). So we also “wait eagerly for our adoption to sonship, the redemption of our bodies” (v. 23). James’s final exhortation in his letter is a call to the church to bring back anyone who “should wander from the truth” (5:19–20), and the Book of Hebrews speaks of our redemption from death itself (2:14–15).

Repair is there at the end, too, as the Anglican theologian N. T. Wright has reminded a new generation of Christians. “The God in whom we believe is the creator of the world, and he will one day put this world to rights,” Wright preached in 2006, drawing on Isaiah 35, Luke 10, and the Book of Revelation.

That solid belief is the bedrock of all Christian faith. God is not going to abolish the universe of space, time, and matter; he is going to renew it, to restore it, to fill it with new joy and purpose and delight, to take from it all that has corrupted it.

Indeed, Wright added, this is a work God has already begun: He “has come with healing and hope in Jesus Christ, has picked up the battered and dying world, and has bound up its wounds and set it on the road to full health.”

Repair is one way we can imitate Christ, one way to prefigure the resurrection and renewed creation.

Or it could be, anyway, if we did it.

“Sometimes the task of rebuilding,” Newhouse wrote in an earlier Tablet essay, “is so daunting that it can almost feel easier to believe it can’t be done.”

I suspect our tendency against repair is self-perpetuating. The more we feel everything is broken—that trust is a fool’s errand, that our institutions are irreversibly rotten, that dictatorship is inevitable, that demolition is all we can do—the more likely we are to resign ourselves to decay, to let wounds fester, to forget techniques of mending, and perhaps to actively exacerbate chaos. The problem is cumulative.

This is how even Christians end up “watching the walls of a healthy society come down, with little vision or motivation to repair them,” as reconciliation scholar Brenda Salter McNeil describes in Empowered to Repair.

Much of McNeil’s book is a practical engagement with the biblical repair story of Nehemiah, in which the titular leader, through prayer and diligence, leveraged his favor with a foreign king to rebuild the ransacked walls of Jerusalem. This attention to practice and skill—to all the learning and labor those Instagram videos skip—is part of what we need to cultivate a tendency toward repair. But the vision McNeil mentions is necessary too.

When I first began thinking about repair, I cast around to see who else was talking about the topic in evangelical circles (McNeil’s book hadn’t yet been published).

The voice I most often encountered was that of Patrick Miller, a pastor, author, and podcaster based in Columbia, Missouri, whom I’d briefly met a few years ago.

“I’ve been hesitant to embrace the idea [of] ‘cultural repair,’” Miller wrote on social media last year, because it risks being mistaken for a call to return to wrongheaded or outright evil patterns of history. “I don’t want to repair segregation or Jim Crow,” he added.

But if we’re thinking about institutions—especially the church—talking in terms of repair makes sense. He continued:

Institutions are houses. Places we live in. To repair a house that’s been neglected or intentionally deconstructed, is to make a space for future living. Anyone familiar with home repair knows you have to remove asbestos and lead (i.e. the problems of the past) to make the house livable.

Miller expanded on this thesis in an essay for Mere Orthodoxy, where he likewise spoke of vision. American evangelicals have plenty of vision for movements and institutions, Miller argued, but it is overwhelmingly a negative vision rather than a positive one (or, I would add, a tendency against repair rather than toward it).

Even many who in theory advocate for moving from critique to creativity, Miller contended, have nothing positive to offer in practice. That is, as he told me in an interview, we are very good at articulating what we’re against but have a harder time explaining what we’re for, what we’re trying to build, what kind of life we’re pursuing with one another.

Maybe that’s because we do not know where or how to begin. My hope for my own local church includes a heavy focus on catechesis, thick community, and deliberate boundaries on digital distractions that impede thoughtful life together.

But wanting these goods is not the same as knowing how to build and maintain them. And when I think about trying to pass this positive vision on to younger generations in a tech-obsessed, atomized culture—to teach at a congregational (or even movement) scale that these are goods worth repairing—well, suffice it to say I feel blessed not to be in pastoral ministry.

That pessimism is why one piece of Miller’s own positive vision intrigued me: He thinks that Zoomers—members of Gen Z, born roughly from 1997 to 2012—could be our era’s Nehemiahs, starting to rebuild the American church after a century of decline, distortion, and deconstruction.

I’m skeptical. After all, Zoomers grew up in the same repair-averse culture as the rest of us, and if we think about characteristic contemporary challenges to our faith (smartphones not least among them), surely the youngest adults, the “anxious generation,” have gotten the worst of it.

Miller agreed when we spoke that “Zoomers drew the short straw,” with their childhoods distorted and their very brains rewired to the point that we might deem them past repair. But he argues that at least a portion of Gen Z is more aware of the impact of isolation on their social development. They understand that they were made for community because they know what it feels like to be alone, he said.

“I have seen in pastoral ministry that it’s often people who experience the greatest healing and transformation who have the greatest ability to offer that to others,” Miller told me. “I think about Jesus when he talked about those who need a healer: It’s the sick who know that they need a healer, not the well” (Luke 5:31).

He sees less interest in the younger generation in “negative visions and burning things down” than in building and repairing institutions, including the church. There’s a receptivity to a positive vision, if we have one to offer, for “how we pray, how we read, how we treat one another, how we treat our neighbors”—and, Miller added, how “we train within ourselves a readiness to do good.”

A church that relearns how to repair would still have sins in need of exposure, wounds in need of debridement, errors in need of deconstruction. But for every thesis we nail to the door, we might fix a broken hinge or putty an old crack. We might be known less for our mutual antagonism and more as repairers of broken walls. With time and faithfulness, maybe we can pass on to future generations a hard-won tendency toward repair.

Bonnie Kristian is editorial director of ideas and books at Christianity Today.