NEWS

Christianity in the World Today

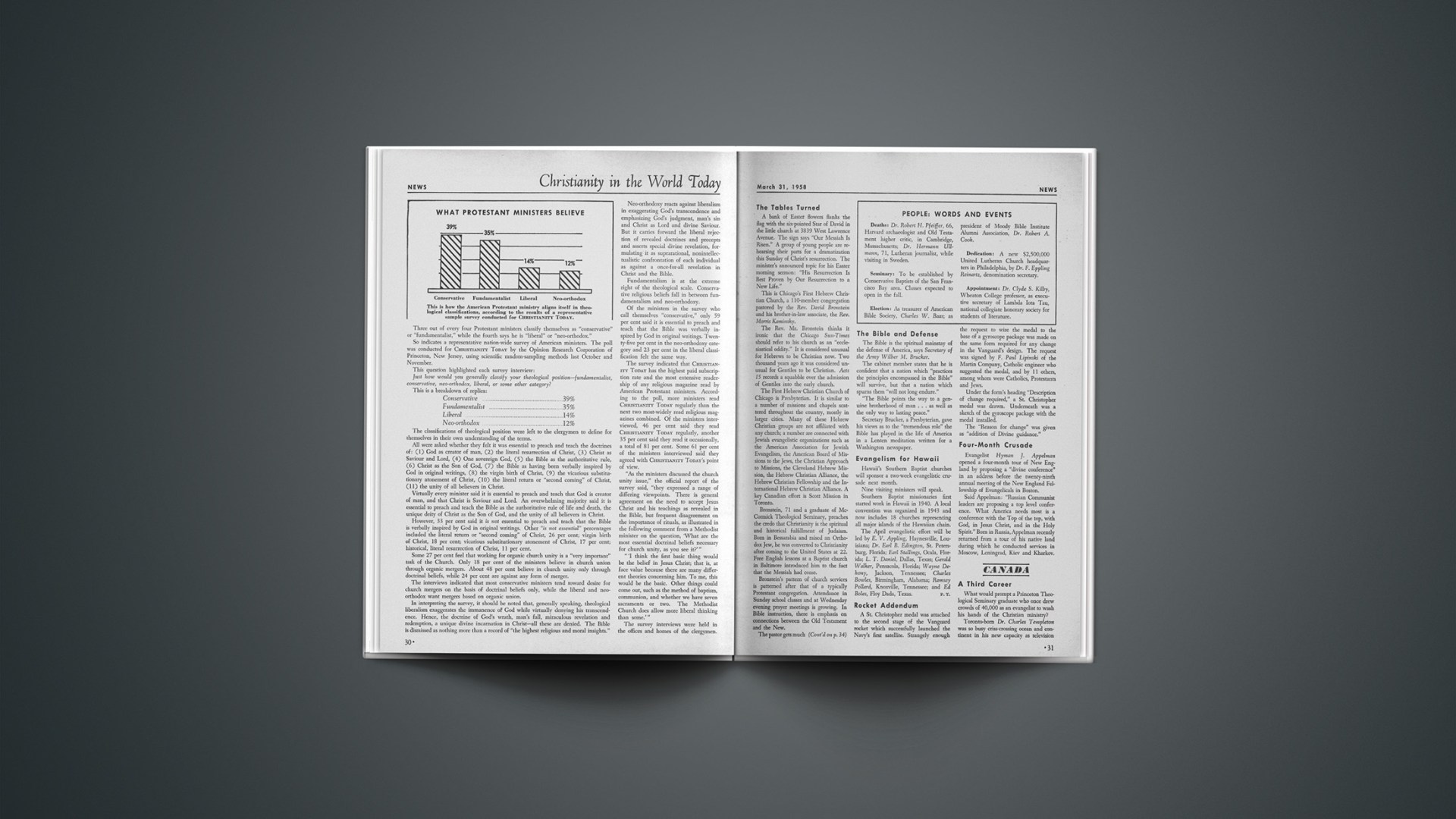

Three out of every four Protestant ministers classify themselves as “conservative” or “fundamentalist,” while the fourth says he is “liberal” or “neo-orthodox.”

So indicates a representative nation-wide survey of American ministers. The poll was conducted for CHRISTIANITY TODAY by the Opinion Research Corporation of Princeton, New Jersey, using scientific random-sampling methods last October and November.

This question highlighted each survey interview:

Just how would you generally classify your theological position—fundamentalist, conservative, neo-orthodox, liberal, or some other category?

This is a breakdown of replies:

The classifications of theological position were left to the clergymen to define for themselves in their own understanding of the terms.

All were asked whether they felt it was essential to preach and teach the doctrines of: (1) God as creator of man, (2) the literal resurrection of Christ, (3) Christ as Saviour and Lord, (4) One sovereign God, (5) the Bible as the authoritative rule, (6) Christ as the Son of God, (7) the Bible as having been verbally inspired by God in original writings, (8) the virgin birth of Christ, (9) the vicarious substitutionary atonement of Christ, (10) the literal return or “second coming” of Christ, (11) the unity of all believers in Christ.

Virtually every minister said it is essential to preach and teach that God is creator of man, and that Christ is Saviour and Lord. An overwhelming majority said it is essential to preach and teach the Bible as the authoritative rule of life and death, the unique deity of Christ as the Son of God, and the unity of all believers in Christ.

However, 33 per cent said it is not essential to preach and teach that the Bible is verbally inspired by God in original writings. Other “is not essential” percentages included the literal return or “second coming” of Christ, 26 per cent; virgin birth of Christ, 18 per cent; vicarious substitutionary atonement of Christ, 17 per cent; historical, literal resurrection of Christ, 11 per cent.

Some 27 per cent feel that working for organic church unity is a “very important” task of the Church. Only 18 per cent of the ministers believe in church union through organic mergers. About 48 per cent believe in church unity only through doctrinal beliefs, while 24 per cent are against any form of merger.

The interviews indicated that most conservative ministers tend toward desire for church mergers on the basis of doctrinal beliefs only, while the liberal and neo-orthodox want mergers based on organic union.

In interpreting the survey, it should be noted that, generally speaking, theological liberalism exaggerates the immanence of God while virtually denying his transcendence. Hence, the doctrine of God’s wrath, man’s fall, miraculous revelation and redemption, a unique divine incarnation in Christ—all these are denied. The Bible is dismissed as nothing more than a record of “the highest religious and moral insights.”

Neo-orthodoxy reacts against liberalism in exaggerating God’s transcendence and emphasizing God’s judgment, man’s sin and Christ as Lord and divine Saviour. But it carries forward the liberal rejection of revealed doctrines and precepts and asserts special divine revelation, formulating it as suprarational, nonintellectualistic confrontation of each individual as against a once-for-all revelation in Christ and the Bible.

Fundamentalism is at the extreme right of the theological scale. Conservative religious beliefs fall in between fundamentalism and neo-orthodoxy.

Of the ministers in the survey who call themselves “conservative,” only 59 per cent said it is essential to preach and teach that the Bible was verbally inspired by God in original writings. Twenty-five per cent in the neo-orthodoxy category and 23 per cent in the liberal classification felt the same way.

The survey indicated that CHRISTIANITY TODAY has the highest paid subscription rate and the most extensive readership of any religious magazine read by American Protestant ministers. According to the poll, more ministers read CHRISTIANITY TODAY regularly than the next two most-widely read religious magazines combined. Of the ministers interviewed, 46 per cent said they read CHRISTIANITY TODAY regularly, another 35 per cent said they read it occasionally, a total of 81 per cent. Some 61 per cent of the ministers interviewed said they agreed with CHRISTIANITY TODAY’S point of view.

“As the ministers discussed the church unity issue,” the official report of the survey said, “they expressed a range of differing viewpoints. There is general agreement on the need to accept Jesus Christ and his teachings as revealed in the Bible, but frequent disagreement on the importance of rituals, as illustrated in the following comment from a Methodist minister on the question, ‘What are the most essential doctrinal beliefs necessary for church unity, as you see it?’ ”

“ ‘I think the first basic thing would be the belief in Jesus Christ; that is, at face value because there are many different theories concerning him. To me, this would be the basic. Other things could come out, such as the method of baptism, communion, and whether we have seven sacraments or two. The Methodist Church does allow more liberal thinking than some.’ ”

The survey interviews were held in the offices and homes of the clergymen.

The Tables Turned

A bank of Easter flowers flanks the flag with the six-pointed Star of David in the little church at 3859 West Lawrence Avenue. The sign says “Our Messiah Is Risen.” A group of young people are rehearsing their parts for a dramatization this Sunday of Christ’s resurrection. The minister’s announced topic for his Easter morning sermon: “His Resurrection Is Best Proven by Our Resurrection to a New Life.”

This is Chicago’s First Hebrew Christian Church, a 110-member congregation pastored by the Rev. David Bronstein and his brother-in-law associate, the Rev. Morris Kaminsky.

The Rev. Mr. Bronstein thinks it ironic that the Chicago Sun-Times should refer to his church as an “ecclesiastical oddity.” It is considered unusual for Hebrews to be Christian now. Two thousand years ago it was considered unusual for Gentiles to be Christian. Acts 15 records a squabble over the admission of Gentiles into the early church.

The First Hebrew Christian Church of Chicago is Presbyterian. It is similar to a number of missions and chapels scattered throughout the country, mostly in larger cities. Many of these Hebrew Christian groups are not affiliated with any church; a number are connected with Jewish evangelistic organizations such as the American Association for Jewish Evangelism, the American Board of Missions to the Jews, the Christian Approach to Missions, the Cleveland Hebrew Mission, the Hebrew Christian Alliance, the Hebrew Christian Fellowship and the International Hebrew Christian Alliance. A key Canadian effort is Scott Mission in Toronto.

Bronstein, 71 and a graduate of McCormick Theological Seminary, preaches the credo that Christianity is the spiritual and historical fulfillment of Judaism. Born in Bessarabia and raised an Orthodox Jew, he was converted to Christianity after coming to the United States at 22. Free English lessons at a Baptist church in Baltimore introduced him to the fact that the Messiah had come.

Bronstein’s pattern of church services is patterned after that of a typically Protestant congregation. Attendance in Sunday school classes and at Wednesday evening prayer meetings is growing. In Bible instruction, there is emphasis on connections between the Old Testament and the New.

The pastor gets much of his message across through individual, personal contacts. Here he describes a conversion:

“Mr. X was brought up in an Orthodox Jewish home in Chicago. Eight years ago he met a non-Jewish girl, fell in love and married her. As is often the case in such mixed marriages, they agreed that neither of them would bother with religion.

“As Mr. X tells us now, his wife was restless and discontent. He gave her everything she asked for, but still she was dissatisfied. She learned about the Hebrew Christian Church and began attending the services. Last October she persuaded her husband to attend a special Yom Kippur. After that, both began coming to church regularly, along with their three children.

“A short time after Mr. X began coming to the church services, we invited him and his wife to our home for dinner. After dinner we brought the Bible to the table. We began a series of six Bible studies. On the last evening I suggested that he come by himself for a final lesson. He came. We reviewed briefly the last three messages, pointing out how these lessons apply to him personally. We showed him how he could have an acquaintance with God if he opened his mouth and asked God to forgive his sins and put a new heart and new spirit into him (See Ezek. 36:24–27). This prayer has to be prayed in the name of Christ, who by his death has made it possible for God to forgive and forget our sins (Jer. 31:34). He prayed thus, and immediately something took place in his heart.

“Last Christmas the wife wrote on a Christmas card: ‘Dear Mr. and Mrs. B. Thank you for leading my husband to Christ. This is the first happy Christmas we have had together since we were married.’ ”

People: Words And Events

Deaths: Dr. Robert H. Pfeiffer, 66, Harvard archaeologist and Old Testament higher critic, in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Dr. Hermann Ullmann, 71, Lutheran journalist, while visiting in Sweden.

Seminary: To be established by Conservative Baptists of the San Francisco Bay area. Classes expected to open in the fall.

Election: As treasurer of American Bible Society, Charles W. Baas; as president of Moody Bible Institute Alumni Association, Dr. Robert A. Cook.

Dedication: A new $2,500,000 United Lutheran Church headquarters in Philadelphia, by Dr. F. Eppling Reinartz, denomination secretary.

Appointment: Dr. Clyde S. Kilby, Wheaton College professor, as executive secretary of Lambda Iota Tau, national collegiate honorary society for students of literature.

The Bible And Defense

The Bible is the spiritual mainstay of the defense of America, says Secretary of the Army Wilber M. Brucker.

The cabinet member states that he is confident that a nation which “practices the principles encompassed in the Bible” will survive, but that a nation which spurns them “will not long endure.”

“The Bible points the way to a genuine brotherhood of man … as well as the only way to lasting peace.”

Secretary Brucker, a Presbyterian, gave his views as to the “tremendous role” the Bible has played in the life of America in a Lenten meditation written for a Washington newspaper.

Evangelism For Hawaii

Hawaii’s Southern Baptist churches will sponsor a two-week evangelistic crusade next month.

Nine visiting ministers will speak.

Southern Baptist missionaries first started work in Hawaii in 1940. A local convention was organized in 1943 and now includes 18 churches representing all major islands of the Hawaiian chain.

The April evangelistic effort will be led by E. V. Appling, Haynesville, Louisiana; Dr. Earl B. Edington, St. Petersburg, Florida; Earl Stallings, Ocala, Florida; L. T. Daniel, Dallas, Texas; Gerald Walker, Pensacola, Florida; Wayne Dehony, Jackson, Tennessee; Charles Bowles, Birmingham, Alabama; Ramsey Pollard, Knoxville, Tennessee; and Ed Boles, Floy Dada, Texas.

P. T.

Rocket Addendum

A St. Christopher medal was attached to the second stage of the Vanguard rocket which successfully launched the Navy’s first satellite. Strangely enough the request to wire the medal to the base of a gyroscope package was made on the same form required for any change in the Vanguard’s design. The request was signed by F. Paul Lipinski of the Martin Company, Catholic engineer who suggested the medal, and by 11 others, among whom were Catholics, Protestants and Jews.

Under the form’s heading “Description of change required,” a St. Christopher medal was drawn. Underneath was a sketch of the gyroscope package with the medal installed.

The “Reason for change” was given as “addition of Divine guidance.”

Four-Month Crusade

Evangelist Hyman J. Appelman opened a four-month tour of New England by proposing a “divine conference” in an address before the twenty-ninth annual meeting of the New England Fellowship of Evangelicals in Boston.

Said Appelman: “Russian Communist leaders are proposing a top level conference. What America needs most is a conference with the Top of the top, with God, in Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Spirit.” Born in Russia, Appelman recently returned from a tour of his native land during which he conducted services in Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev and Kharkov.

Canada

A Third Career

What would prompt a Princeton Theological Seminary graduate who once drew crowds of 40,000 as an evangelist to wash his hands of the Christian ministry?

Toronto-born Dr. Charles Templeton was so busy criss-crossing ocean and continent in his new capacity as television producer that he hardly could find time to explain.

“If you’re going to preach effectively,” said the 42-year-old Templeton as he left for Rome and Cairo to secure personality interviews for TV, “you have to have conviction. My convictions as to some aspects of Christian doctrine became diluted with doubt. I don’t say I’m right and all others are wrong. But feeling as I do, I could not go on in the ministry. So I left.”

Templeton’s new vocation is his third. At 17 he joined the Toronto Globe as a cartoonist, but within five years he was active as an evangelist. He won respect as a minister by building Toronto’s Avenue Road Church from virtual nothingness into one of the largest congregations in the city. He became swamped with invitations to address church services and evangelistic rallies across America and Canada. He was one of the first executives of the Youth for Christ movement.

When Templeton went to Princeton Seminary, his convictions veered to neo-orthodoxy. Now he views his pre-Princeton formal theological training as “superficial.”

Ordained a Presbyterian minister in 1951, Templeton became the first fulltime evangelist for the National Council of Churches. Three years later he resigned to become secretary of the evangelism division of the Presbyterian Church in the U. S. A. He resigned that post in 1956.

Since last June, Templeton has been writing plays for a Canadian television network. His “Love Is a Punch on the Jaw” is the story of a pacifist minister who finds himself in a position where violence is inescapable. Another of Templeton’s plays is titled “Absentee Murderer.” He is also a performer on CBC-TV’s “Close-Up.”

Last year, Templeton and his wife parted via an amicable, uncontested divorce issued in Juarez, Mexico. The former Mrs. Templeton, who once sang at her husband’s meetings, has since remarried.

Templeton’s marital problems were reported to have played no part in his decision to leave the church. But he has been quoted as saying that had he continued in the ministry, there would have been no divorce.

“The decision to change my vocation was a slow and painful one,” said Templeton. “I could continue to preach, with mental reservations, or accept the alternative and leave the ministry. It became clear to me that I had no other choice.”