If a good deed done is not posted on social media, did it really happen? If an act of generosity is not caught on camera and never goes viral, was it a worthwhile gesture? These questions, facetious as they seem, point out something I’ve observed in my own life: a deep desire to display my goodness to others. There’s even a modern term for it: virtue signaling.

According to Jesus, this is an ancient struggle, a primal temptation. We long to be known and seen, but if we aren’t careful, this longing can lead to a kind of performativity that corrodes the soul.

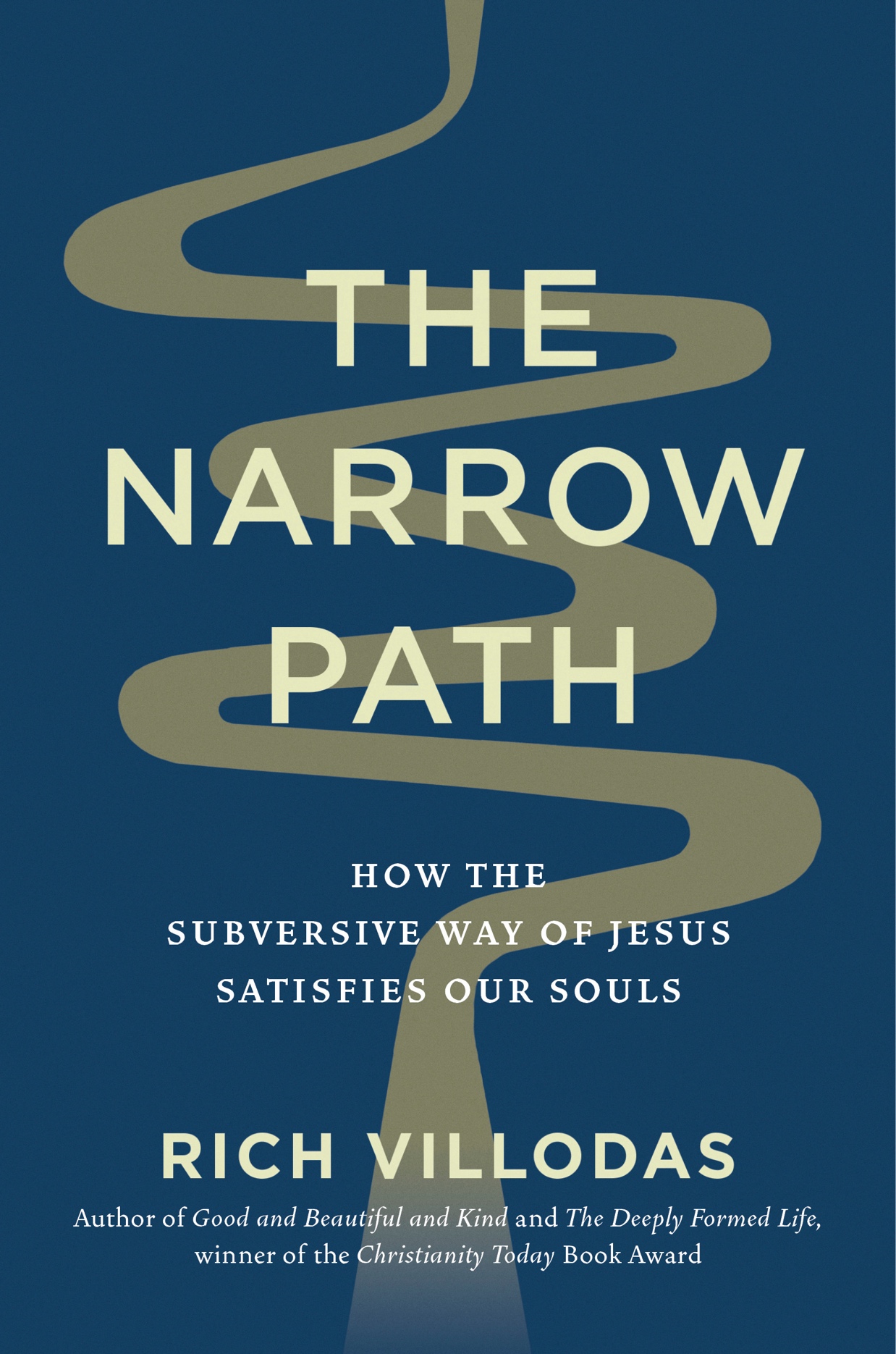

In Matthew 6—the center of the Sermon on the Mount—Jesus flips showy spirituality on its head: “Be careful not to practice your righteousness in front of others to be seen. … But when you give to the needy, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing” (vv. 1, 3). Jesus reveals a key characteristic of his narrow path: hiddenness.

That is an important word for those who, like me, intuitively strive to be noticed. Can you relate? Social media has created (or perhaps revealed) the hunger within us to be seen. As some have aptly said, the current generation of young adults—and emerging ones—can be described as “Generation Notification.”

Each time we get notifications—those coveted red or blue circles with a number in them—dopamine releases in our brains. The cycle is hard to break. Even if a comment is negative, receiving one is still addicting because being seen is better than remaining invisible.

To be known and seen is one of our deepest longings. But left to our own devices (pun intended), we get stuck in a never-ending cycle of performative spirituality, where we seek to get from others what can be given only by God.

Jesus’ warning to us, then, is not just good spirituality; it’s good psychology. To be his disciple requires being a whole person, not merely doing religious things. What often stands in the way is a lack of self-awareness—not knowing our inner selves. How do we overcome this?

To combat the unrelenting desire to be seen by others, we are called by Jesus to hiddenness. Once again, the paradox of the kingdom of God is evident. The narrow path of Jesus says that if we want to be strong, we must be weak; if we want to be first, we must be last; if we want to be great, we must be least. It’s the same pattern here: To be truly seen, we must be hidden.

This hiddenness is challenging because Jesus doesn’t primarily mean hiddenness from the world; he means hiddenness from ourselves. To better understand this, it might be helpful to contrast good self-awareness with bad self-awareness.

Good self-awareness sees areas of our lives that are constraining us. It helps us name the forces that keep us from living free, full, and loving lives. Good self-awareness focuses on our reactions and triggers. It reflects on the things we’ve done, and the things left undone. Good self-awareness leads to humility and invites us into a process of growth.

When Jesus says, “Do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing” (Matt. 6:3), he invites you into a “holy unawareness.”

Which leads me to the temptation of bad self-awareness. Self-awareness becomes damaging when the focus is on our righteousness, when we’re caught up in our own goodness, living a self-congratulatory existence. Bad self-awareness fixates on our deeds and exaggerates our spiritual growth. There have been many times when I’ve obsessed over my progress.

When I exercise, I tend to look in the mirror way more than I need to. After 25 pushups, my chest feels like that of a professional bodybuilder, so I go to the mirror to confirm my suspicions (and am sorely disappointed each time). My tendency to document my growth roots me in despair or pride, depending on the day. In all this, I’ve discovered that the most mature people are not consumed with their fruitfulness, nor do they wallow in their failures.

It’s exhausting to live a life of performance. Jesus offers a better way. Aren’t you tired of always having to be “on”? Isn’t it draining to work for constant approval? Do you ever feel as though God will be disappointed if you don’t have everything in order?

Jesus doesn’t lead us into a scrupulous spirituality in which we agonize over every decision. Rather, he calls us to examine the ground from which our good deeds grow. Why? So we don’t entrap ourselves in self-righteousness or idolatry: self-righteousness because our goodness can cloud the grace of God; idolatrous because, without knowing it, we worship acclaim from others instead of from God.

When our deeds are practiced in front of others, we forfeit the rewards we will receive from the Father. Instead of receiving commendation from God, we settle for admiration from people. Of course, Jesus is not saying that all recognition and reward is incongruent with life in the kingdom. He’s clarifying that to live for it is folly. Applause from others, social media likes—it all fades quickly. Only the affirming word of the Father can fill our hearts.

What does this hiddenness look like in real life? Because Jesus embodied it perfectly, let’s consider his life for guidance.

Let this blow your mind: Jesus spent 30 of his 33 years on earth (about 90 percent of his life) in relative obscurity. As someone who regularly leads and speaks in front of lots of people, I find this so challenging. Ron Rolheiser explained how we can follow Jesus’ example: “Ordinary life can be enough for us, but only if we first undergo the martyrdom of obscurity and enter Christ’s hidden life.”

To value hiddenness doesn’t mean we must become members of a monastery, tucked away from the world. Rather, hiddenness is freedom from the shallow praise of the world.

In the Gospels, Jesus is constantly swarmed by admirers of his teaching and miracles, yet he refuses to capitalize on it. In modern terms, he doesn’t post selfies (#LeperBeClean). On one occasion, when people are amazed at his miracles, here’s how Jesus responds: “While he was in Jerusalem at the Passover Festival, many people saw the signs he was performing and believed in his name. But Jesus would not entrust himself to them” (John 2:23–24).

Even when people want to make him a celebrity, Jesus holds back. He’s not wooed by platform. Even in his resurrection, Jesus prizes hiddenness. If it were me, I would show up at the home of those who crucified me to scare them to death and demonstrate my power over all things. Jesus, however, simply finds his friends and, rather than storming the world, tells them to share the good news.

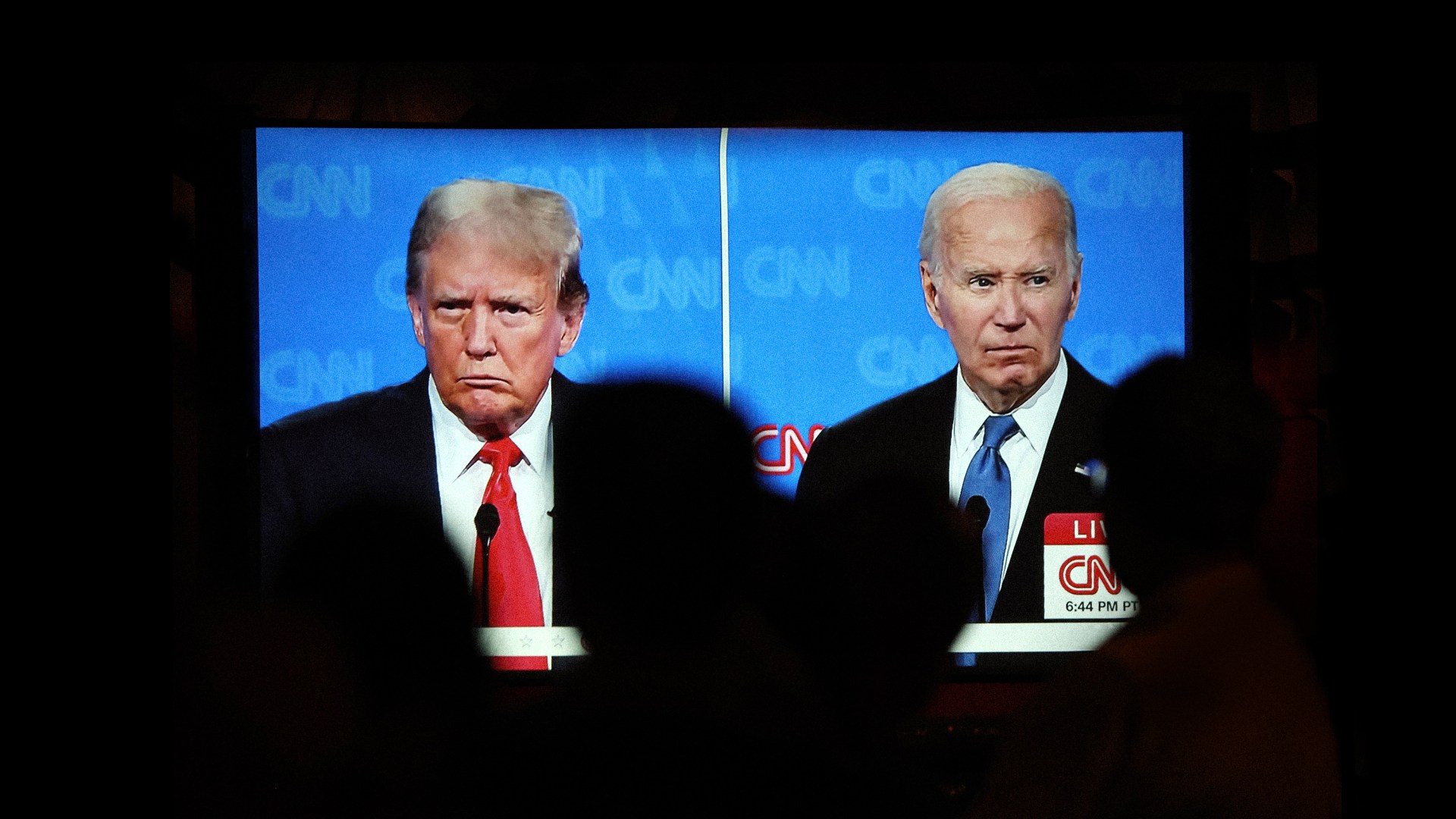

To live this way is difficult, especially for those of us who use social media. It lures us into believing the primordial lie of the serpent: You can be like God (Gen. 3:5). Social media creates the illusion that we can know all things, be everywhere, and use our words for the sake of power. It’s the seductive lie that we can be omniscient, omnipresent, and omnipotent.

What’s stunning about God’s kingdom is that even though he is all-powerful, all-knowing, and everywhere-present, his presence and activity are often centered in places far from the masses:

In the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar—when Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea, Herod tetrarch of Galilee, his brother Philip tetrarch of Iturea and Traconitis, and Lysanias tetrarch of Abilene—during the high-priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas, the word of God came to John son of Zechariah in the wilderness. (Luke 3:1–2)

Luke lists all the political and religious leaders in power, then surprisingly highlights how the word of God bypassed them and came to John in the wilderness. The locus of God’s presence and activity is not found in the corridors of great power. The Gospels tell of a God who shows up in surprising places. His greatest place of action is hidden from the eyes of the socially powerful. His reach touches everything, but the center of it is hidden.

One of Jesus’ best lessons on the importance of hiddenness is something he says about the Holy Spirit. It’s easy to miss if you’re not looking for it, so let’s slow down and take a look.

While wrapping up his time with his disciples before going to the cross, he utters this poignant line about the Holy Spirit: “When he, the Spirit of truth, comes, he will guide you into all the truth. He will not speak on his own; he will speak only what he hears, and he will tell you what is yet to come” (John 16:13). Eugene Peterson paraphrased Jesus’ words, saying the Spirit “won’t draw attention to himself” (MSG). That is why some people refer to him as the “Hidden Spirit.”

The Holy Spirit shows deference to Jesus. His inclination is to spotlight another rather than hog the limelight, delighting in making the Son central. Jesus says, “He will glorify me because it is from me that he will receive what he will make known to you” (v. 14).

Within the Trinity, there is no jockeying for position. The three persons are radically other-focused. Just look at how their interaction is recorded in Scripture. The Father affirms the Son. “This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased. Listen to him!” (Matt. 17:5). The Son is always pointing to the Father. Jesus says things like, The Father is greater than all. I do only what I see my Father doing (John 5:19, 14:28). And the Spirit always points to the Son.

Here’s the main idea: If the Spirit is secure in the love of the Trinity and if the Spirit lives inside you, he wants to make you secure too. He wants to remind you that you are loved by God. You are accepted by God. But ordering life around that theological truth requires concrete, counter-instinctual practices. We must remind ourselves what it looks like to live an anti-performance life like Christ—and to get off the treadmill of endless posturing.

Excerpted from The Narrow Path by Rich Villodas. Copyright © 2024 by Richard A. Villodas. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Rich Villodas is the best-selling author of The Deeply Formed Life (winner of the Christianity Today Book Award) and Good and Beautiful and Kind. He is the lead pastor of New Life Fellowship, a large multiracial church with more than 75 countries represented, in Elmhurst, Queens, and Long Island, New York.