On Sunday, June 21, 2020, 18-year-old Linda Stoltzfoos of Bird-in-Hand, Pennsylvania, was kidnapped and later murdered by Justo Smoker—my brother-in-law.

As you might expect, my family journeyed through tremendous grief, anger, and pain. But as you might not expect, we also journeyed through the challenge of receiving unexplainable grace, kindness, and mercy at the hands of the Amish community, of which Linda Stoltzfoos was a part.

The story to be told is not just another story of grief and healing but a story about the gospel. It’s a gospel story embedded in the very tangible way the Amish community poured out grace and mercy on my family—and our struggle to receive it. As a pastor for over 20 years, I have preached the gospel countless times, but through my encounters with the Amish community, it was preached to me in a way that was deeper and more personal than anything I’ve ever encountered before.

Many years ago, I memorized Paul’s words in Ephesians 2:8–9: “For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith—and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God—not by works, so that no one can boast.” But in the last four years, for the first time in my life, I’ve had to wrestle with what it really means to receive unmerited grace when there is absolutely nothing you can do to make things better on your own. My family experienced what it’s like when undeserved mercy confronts undeniable evil, when kindness upends condemnation, when heaven engages hell.

This experience began with a knock on the door that I had no interest in answering. I was in no mood to talk to anyone just a few hours after it became public that Justo was charged with Linda’s kidnapping. My shoulders dropped and I thought to myself, “Oh, come on. I don’t have energy to interact with anyone right now.” Sitting there at the kitchen table, I just wanted them to go away.

What got me up from the kitchen table was fear. I was afraid it might be the FBI or police looking for more information or needing something else. Also, I realized I probably should take responsibility to face whoever was there, because the alternative was to wait long enough that my daughter would feel compelled to get the door. As good as avoidance sounded, I didn’t want to put her in that position. I found the energy to get up and drag myself to the door.

I peeked through the side windows next to the door and took a breath. It looked like a young Amish family standing outside. I was immediately relieved—it’s so much more welcoming to see an Amish family than uniformed officers at your door. Then, immediately, before I reached for the door handle, other feelings came over me that I’d never felt when interacting with the Amish until this moment: guilt and shame. I felt more vulnerable than I’ve ever felt opening my front door.

With the door opened, my eyes at once met our neighbor, Mary (name changed for privacy). We’d never really interacted before. She had her four children with her, all very young and all basically unaware of the situation their mom had chosen to enter. Their eyes were full of youthful exuberance, wonder, and interest at coming to our home. Her eyes were full of compassion. I saw no pity there, and certainly no anger—nothing close to that. There was an immediate sensation that she knew what was going on here in a way that few did. Her presence was a gift, and it immediately displaced my guilt and shame.

“I’m Mary, your neighbor,” she said. “And you may not know this, but I was the teacher at Nickel Mines.”

The tears barely stayed in her eyes. As I stood there, I knew she didn’t have to say more. She knew. She knew everything—everything that was about to come our way over the coming season, and everything we would uncover in ourselves, in our community, and in our personal faith in God.

My oldest daughter, Megan, was in kindergarten when Nickel Mines happened. On October 2, 2006, Charles Roberts entered a one-room Amish schoolhouse in Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania, just 15 minutes from our home. He forced the teacher, the aides, and all the boys outside. Inside, he shot ten girls—killing five—then killed himself. Mary was that teacher. She was only in her late teens when this happened.

And here she stood, 14 years later, at our front door. In a way, it seemed like she’d just come from running out the back door of that schoolhouse. The pain was fresh, the wound was deep. But her presence wasn’t only about recognizing that. Mary was doing what so many in her Amish community did right on the heels of Nickel Mines: They forgave. Immediately. And as completely as they could. This posture of forgiveness took on various forms, and, in this moment, what it meant for Mary was that in her right hand she held a handpicked bouquet of flowers and in her left hand a small bag of homegrown cucumbers.

I hate cucumbers. But in that moment, I felt like I loved them. I almost cried over cucumbers. The cucumbers represented to me the manifestation of her deep desire to provide comfort and love to our family. What could really be said or done or offered at this point, given the gravity of the moment? Love could be expressed verbally, but the cucumbers represented to me a grace of someone trying something tangible rather than just being satisfied with words.

And when you’re overwhelmed, even the smallest grace can touch the deepest part of you.

“I brought you some flowers and some cucumbers,” she said. “I hope you like cucumbers.”

“Thank you so much,” I lied. “I really do.”

I took the gifts while she remained standing on our front porch. I learned the kids’ names and thanked her for coming. Then she took a breath, and with glassy eyes said to me, “There is hope. God will take care of you.”

I nodded. To this day, I’m not sure what I said in response. What she said and what she did in that moment were far more important. Mary gave us a gift of grace with her nonjudgmental presence, just hours after learning it was her neighbor’s family that had inflicted this Nickel Mines–like pain on the Amish community once again.

That early visit was a preview of what was to come, though I didn’t know that then. All I knew was that in our two-minute interaction, she had changed the narrative without realizing it.

In the first narrative that we were living, we felt great shame and guilt over the pain inflicted on our community by our family member, whom we love. It would make sense if people around us were angry, particularly the Amish community, and most certainly Linda’s family. We expected to play the role of the ones asking for forgiveness, being silent in the background, having to figure out how to grieve while also absorbing the brunt of pent-up anger in our community for the long weeks between Linda’s disappearance and Justo’s arrest. That was a narrative that made sense, and that we anticipated—though we couldn’t fully verbalize it.

Mary and her cucumbers opened up our hearts to another possible narrative, one that acknowledged the need we all had for healing. We all were wounded. We all deeply needed love, grace, and the gift of personal presence to chase away shame and guilt.

This narrative included the possibility of hope—hope for a future that might not be as dark as the current moment felt. Her narrative acknowledged the pain that would come, but it didn’t leave us there. In eating these cucumbers, it was as if we could taste and see that love is good. It was the kind of love that might just be able to heal.

Mary’s visit made me think that Paul’s words in Romans 8:38–39 might be even grittier than I had experienced in my life to date: “For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Neither death nor life can separate us from the love of Christ? Even if your brother-in-law takes someone’s life? Christ’s love is present in that space?

When I closed the door, I was holding back tears as I held the bag of cucumbers and the vase of flowers in my hands. I was holding love, and I didn’t want to put it down. These gifts weren’t enough to chase away all the pain and hurt—there was still much more of that to come. But in the moment, they gave life and breath and hope and kindness.

That’s what personal visits and cucumbers do. They raise our vision, encourage our soul, give us honest hope that this current sadness might not be forever sadness. Love lifts, lightens, and stabilizes—which was good, because the journey we were starting had plenty more to show us. We would need as much love and grace as we could find.

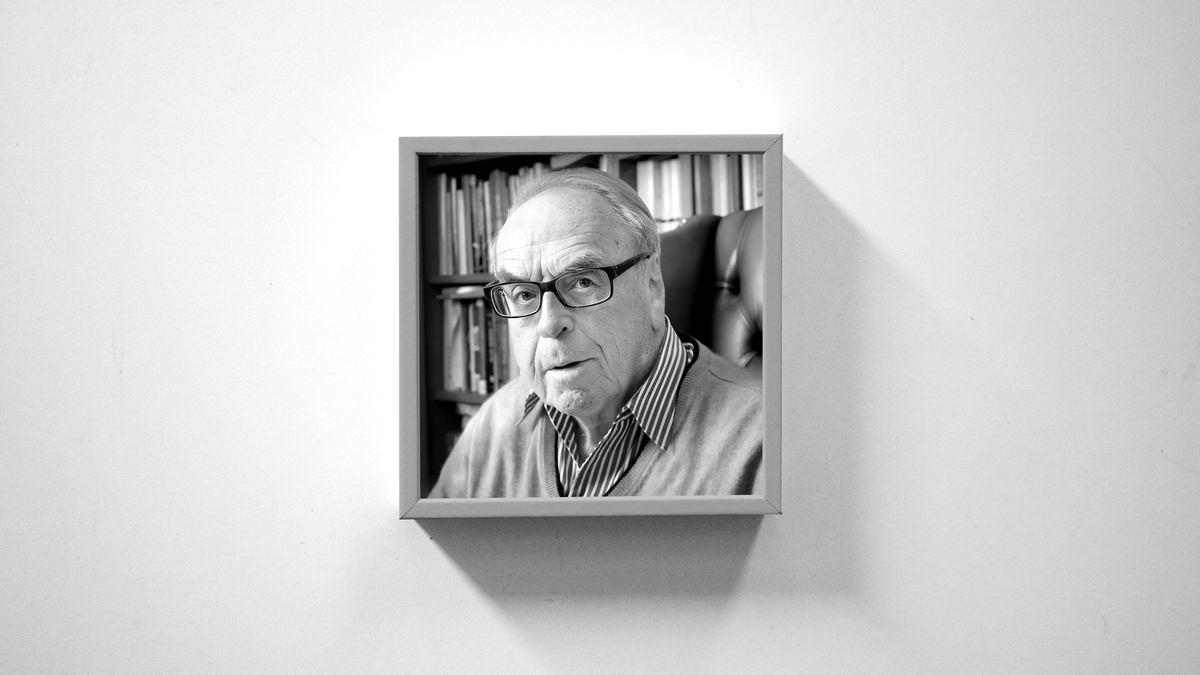

Tim Rogers has served as lead pastor at Grace Point Church of Paradise, Pennsylvania, for more than 20 years and is active in various community roles.

Coauthor Megan Shertzer works as an adult advocate at The Factory Ministries in Paradise, Pennsylvania. Megan is Justo’s niece.

Adapted from Beechdale Road by Megan Shertzer andTim Rogers. ©2024 by Megan Shertzer and Tim Rogers. Used by permission. www.beechdaleroad.com for more information.