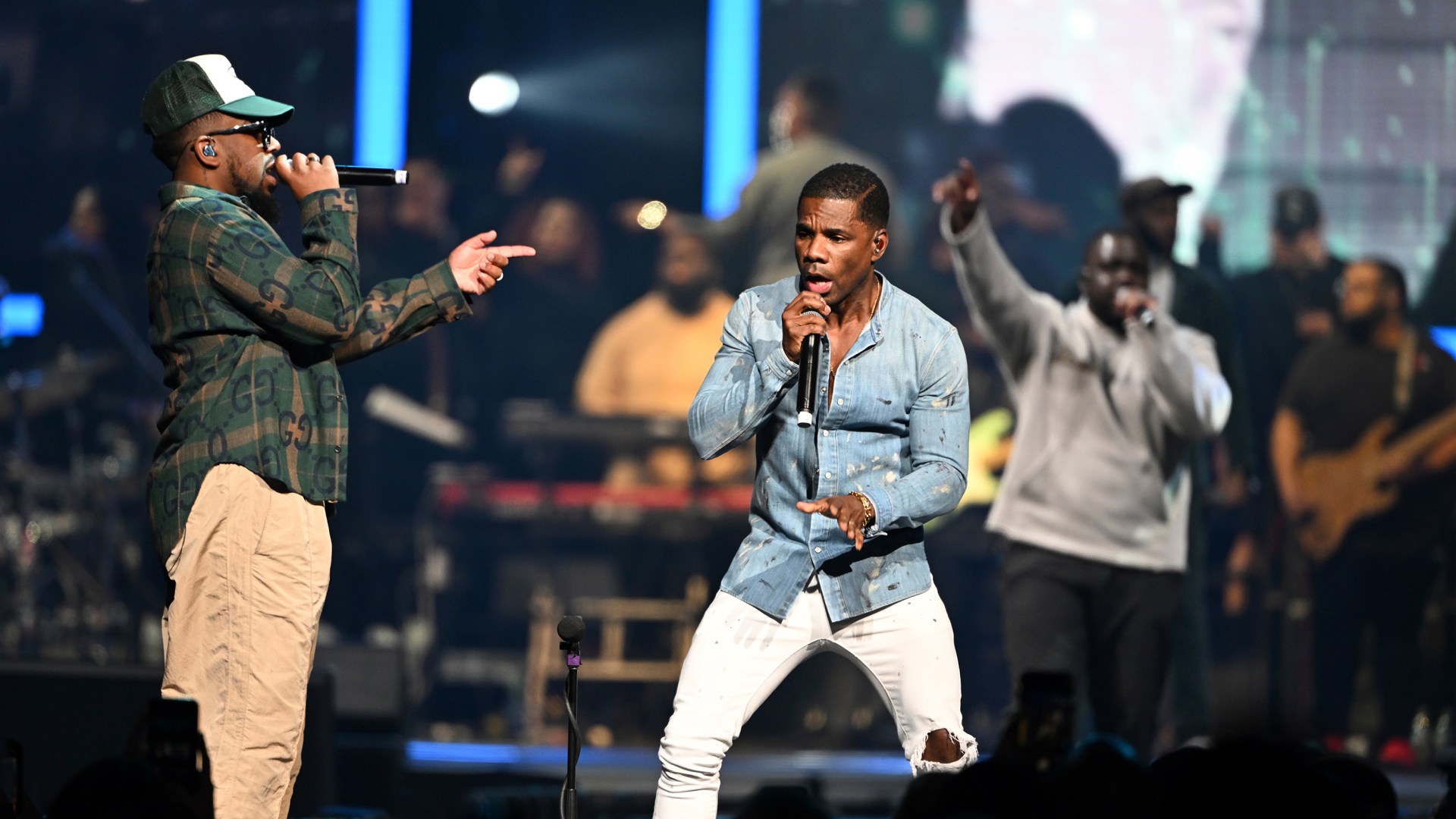

In June, Kirk Franklin and Maverick City Music’s Chandler Moore performed with actor and rapper Will Smith at the BET Awards. Smith premiered his single “You Can Make it” on a dark, smoke-filled stage, standing in a circle of fire with a small choir of vocalists in a raised semicircle behind him. The performance incorporated the sound of a gospel choir and solos by Franklin and Moore, but those nods to Christian music seemed to be in service of a message that was only vaguely spiritual, referring to heaven and hell but focused on personal struggle and triumph.

Though the performance boosted the single to No. 3 on Billboard’s Hot Gospel Songs chart, the performance sparked controversy in Africa, where Franklin and Maverick City Music would soon embark on their Kingdom World Tour (KWT). Some Christians there called the performance “satanic.” News outlets in Zimbabwe reported that some of the opening acts— including Annatoria, winner of The Voice UK and a recent Maverick City Music collaborator—had pulled out of the Harare concert. Others called for a boycott, telling fellow Christians to stay away from the tour, which also made stops in Uganda, Zambia, Malawi, Ghana, South Africa, Tanzania, and Kenya.

Few listened.

Before it finished in August, the KWT drew enthusiastic crowds across Africa, filling arenas and selling out its concert at Kenya’s Uhuru Gardens (a 60,000-person venue).

“It will be a moment in my life that I will never forget,” Franklin said in an interview. “To travel to many countries at one time and to feel the Black experience on this continent and on this planet, and to be reminded how unified we are as Black people—we are just separated by water. We are never separated by spirit.”

Though its overall commercial effect seemed minimal, Franklin and Moore’s BET performance prompted some soul-searching among African Christians about their relationship with American artists, even among those who attended the concert.

Daniel Shirima, a Kenyan emcee and event organizer, said that even as part of the crowd, he was preoccupied with the backlash.

“Many Kenyan Christians, including myself, feel blessed by their songs … but compared to the warm reception of past artists, this felt different,” Shirima told CT. “Some are questioning Kirk Franklin’s walk with God, influencing others not to attend or to feel skeptical.”

The KWT was Maverick City Music’s first performance in Kenya. The group had risen in popularity in the country during the 2020 pandemic, and songs like “Jireh” and “Bless Me” have become some congregations’ favorite worship songs.

Franklin has been popular with Kenyan Christians for over two decades and has performed in the country twice—in 2007 and 2011. Franklin’s 1998 album The Nu Nation Project achieved international success, going double platinum and selling over 3 million copies worldwide. For many Kenyan fans, that album was their introduction to Franklin’s music, and he has remained popular in the country, building a multigenerational audience with his eclectic blend of gospel, R & B, and rap.

The veteran Christian artist has faced increased scrutiny from American and African audiences in recent years in response to videos of suggestive dancing and rap lyrics that some perceive as irreverent or blasphemous. Kenyan gospel artist Jefro Katai said that a 2022 performance in which Franklin rapped the line “the Lion and the Lamb will bow down to the GOAT” (referring to the acronym for “greatest of all time”) gave listeners pause; some heard it as a sacrilegious suggestion that Jesus would pay homage to an artist.

“We are familiar with the teachings of Christ as the Lamb, and we are also called to be sheep,” said Katai. “I think many Christians heard that rap on a surface level and frowned on Kirk.”

The global reach of the American Christian music industry has meant that the public personas of its artists are up for global discussion. Katai said that African Christians have always had to evaluate the influence of American artists and negotiate which differences to accept as cultural rather than moral.

“American artists can have some tattoos and piercings, for example,” he said. “And some of them are liberal in their politics,” pointing out that some conservative Kenyans objected to Franklin’s willingness to appear publicly with liberal American politicians like Vice President Kamala Harris.

However, Katai said, most Kenyan Christians historically have been willing to overlook those differences when an artist’s music seems to be serving the global church. In Shirima’s view, music from the US has served and will continue to serve the African church.

“Africans are generally very supportive of artists whose songs minister to them,” Shirima said. “We’ve seen this with artists like Don Moen and CeCe Winans, whose songs are sung in our churches. We truly appreciate their talents and giftings.”

Kenyan Christians generally listen to an array of music from Nigeria, South Africa, and the US, in large part because of the production quality and because their local industry isn’t big enough to support full-time recording artists.

“That one can be a gospel artist as a profession [in the US] is quite encouraging. But the reality in Africa is that one also needs a second job to make it in gospel. I sense things are changing, but most Christians are still dealing with bread-and-butter issues,” said Kiarie Mwenda, a management consultant and a longtime fan of Kirk Franklin.

For some, the gap between the lived realities of African Christians and American Christian performing artists is a cause for concern. Some suspect that in addition to an imbalance in economic power between African audiences and American artists, there are competing worldviews.

Olivia Kibui, a recent graduate from Daystar University, is convinced that the interests of American Christian artists can’t be neatly separated from the global political and economic landscape.

“Any media from the US always has an agenda. Always. It is never just what you see. And all their machinery is usually involved,” said Kibui. She also insists that American Christian media is partly to blame for the surging interest in New Age and alternative spirituality.

“These tours have more to do with the ideals and ideas of men than God,” she said. “Kenyans since the ’90s have been followers of US evangelical ideas. Generally, American Christianity is very shallow.”

Not all Kenyan Christians are as pessimistic about the influence of American Christian media. Eva Ishengoma, a Tanzanian businesswoman now living in Nairobi, says that Kenyans value the music of Don Moen, Kirk Franklin, and Maverick City Music because it’s good music.

“Kenyans warmly welcome Christian musicians that come from the US. When secular musicians come, they are received well, so long as Kenyans love their music,” she says. “Africans are receptive to artists from the US as long as their songs are hits.”

In recent years, Christian artists like Travis Greene, Todd Dulaney, William McDowell, Lecrae, Andy Mineo, KB, and Trip Lee have performed in Kenya for enthusiastic crowds. The only recent example of strong opposition or backlash to a Christian figure from the US was to charismatic evangelist Benny Hinn when he visited earlier this year.

Although some opening acts dropped out of the Harare concert, the performance in Nairobi went as planned, with Zambian artist Pompi opening the show and performances by Malawian musician Jeremiah Chikhwaza and Bethuel Lasoi, a songwriter and worship leader at Nairobi’s International Christian Centre. The tour wrapped up in the UK at the end of August with a performance at London’s Wembley Arena.

The mixed response of African audiences to Maverick City Music and Kirk Franklin may be a harbinger of intensifying scrutiny American Christian musicians who seek to cultivate a global audience. As American artists leverage social media and translation to reach Christians around the world, their personas, affiliations, and politics are increasingly visible, and perhaps increasingly alienating.

And yet, the music of Kirk Franklin and Maverick City Music has played a significant role in the faith journeys of many Africans, who have forged strong personal connections with the songs themselves and the musicians who wrote or performed them. For some, it seems unfair to brush aside the artists and music that have ministered to them so powerfully.

“On a personal level, the life and music of Kirk has kept me sober,” said Mwenda, reflecting on his decades spent listening to Franklin’s music. “And Maverick City got me through the COVID season.”