The oldest Protestant seminary in the Middle East has a new vision.

Officially founded in 1932 but with origins dating back to the 19th-century missionary movement, the Near East School of Theology (NEST) is operated by the Presbyterian, Anglican, Lutheran, and Armenian Evangelical denominations.

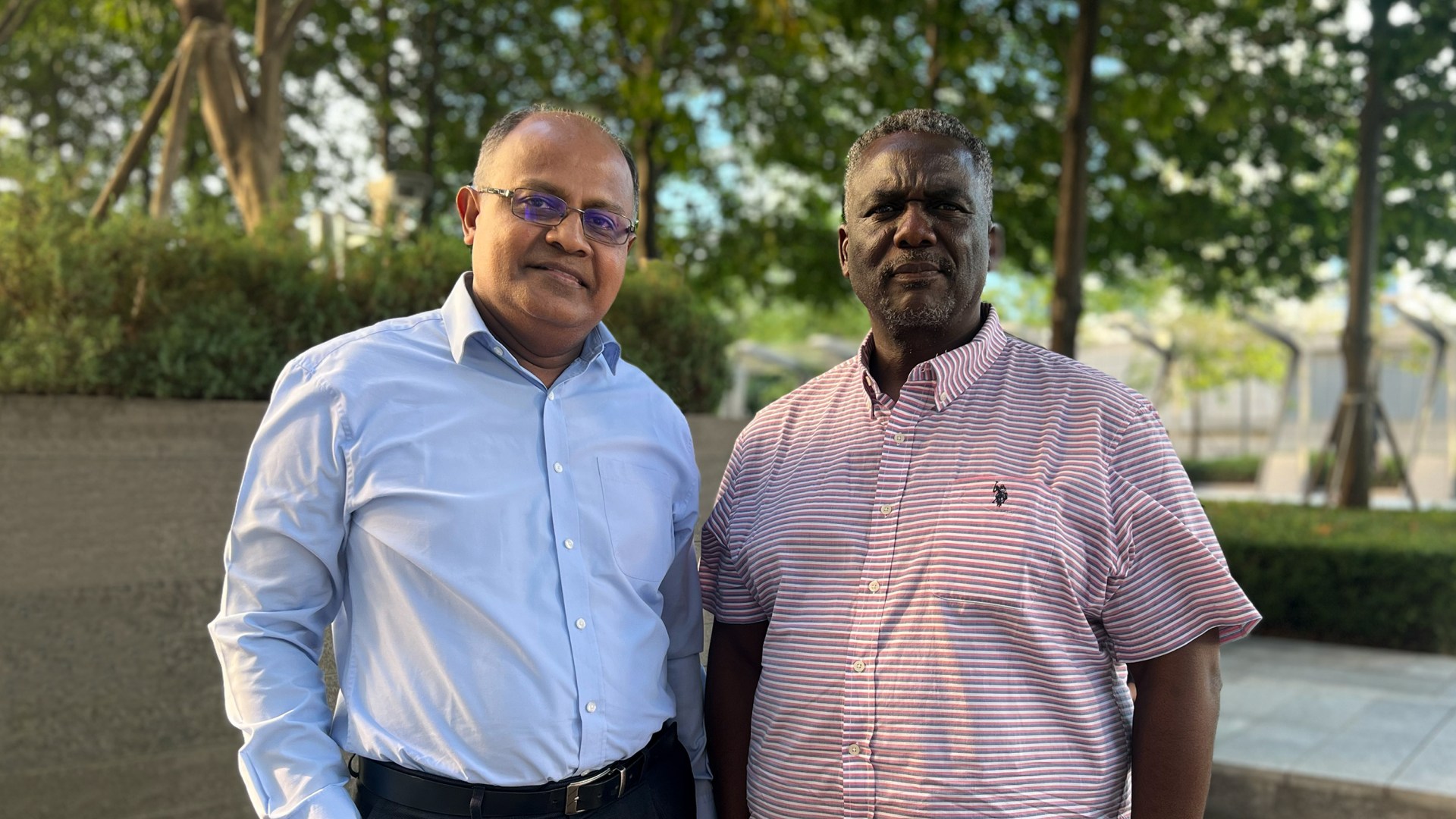

Installed this week, its 11th president is a nondenominational Lebanese evangelical.

Martin Accad, formerly academic dean at Arab Baptist Theological Seminary (ABTS), was installed on Sunday at the historic institution’s Beirut campus. He graduated from NEST in 1996 with a bachelor of theology degree, eventually earning his PhD from the University of Oxford. Awarded scholarships by the World Council of Churches and the evangelical Langham Partnership, Accad is a locally controversial theologian who, like NEST, straddles the liberal-conservative dichotomy.

Author of Sacred Misinterpretation: Reaching Across the Christian-Muslim Divide, Accad has urged believers to approach Islam in a manner that avoids the twin pitfalls of syncretism and polemics. But before joining NEST he resigned his prior academic position at ABTS to apply his biblical convictions within Lebanon’s contested political scene. Creating a research center, his last four years have been spent in pursuit of reconciliation between Lebanon’s often-divided sectarian communities.

Accad will now bring his vision to a new generation of Middle East seminarians.

Although doing public theology is novel for the institution, NEST has long sought, with some struggle, to balance the two streams of its early predecessors’ commitments to evangelistic outreach and service-oriented witness. Its founding in 1932 resulted from a merger of two programs, each with its own distinctives.

One stream of NEST’s roots dates to 1856, when American missionaries began what Accad describes as a discipleship training program in the mountains of Lebanon. Along with providing pastoral development, it functioned as a mission station for sharing the gospel in local villages with non-Protestant Christians and diverse Muslim communities. Its remote location was also designed to isolate these early “seminarians” from the corruption of city life in Beirut.

American outreach to Armenians and Arabs in the Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey) led to the creation of similar schools beginning in 1839. After the Armenian genocide in World War I, these efforts relocated to Athens where they coalesced into a seminary that adopted an ecumenical, Enlightenment-informed model, emphasizing the importance of social service. This was especially true in its approach to Islam—sympathetic and comparative with an eye toward reconciliation.

The merger of these two programs created NEST, which eventually settled in the cosmopolitan Hamra neighborhood of Lebanon’s capital. Although it is situated near three historic Protestant liberal arts colleges—now known as the American University of Beirut (AUB), the Lebanese American University (LAU), and the Armenian-led Haigazian University—early cooperation was shattered by the Lebanese civil war in 1975 and has not been re-established.

Accad wants to restore this collaboration and embody an integration of scholarship and discipleship. CT spoke with him about Protestant distinctives, “electric shock” pedagogy, and how to understand the mainline-evangelical divide in the Middle East.

Why does serving as president of NEST appeal to you?

We need to rethink what it means to be a seminary student today. This question is a key issue globally, but especially in the Middle East. Ideally, the seminary leads the church to be relevant in society. This requires beginning with society and determining its needs. And then the seminary addresses the church—what does the pastor need? Finally, it works backward and designs a program to fit this profile.

Historically, NEST has been an ordination track. This is the traditional model, and it is still necessary if the church believes that it is. But I want to explore with the churches their vision for seminary training, for congregational service, and for regional witness—and how NEST can help prepare leaders to implement this vision.

How do you plan to prepare leaders to serve the church?

Nontraditional, focused tracks are becoming the way people want to learn. Accrediting bodies speak of micro-credentials that may contribute toward academic goals but have value in and of themselves and fit into the bigger puzzle of what students want to do with their lives.

But this system of training should not be only for evangelicals. I want NEST to attract Catholic and Orthodox students also, to think together about how to impact the reality around us. And as we design our programs, I will engage civil society and political activists, where the conversation might be challenging. Many of these people have been turned off by religion due to the sectarian religious landscape of Lebanon, so my interactions with them will be an act of witness.

I can testify on behalf of NEST that God, the church, and theological education are not just internal affairs within the boundaries of our community. No, the church is in society and serves society, and if it is not leading the process of societal change, then it is not following its calling.

How do nonevangelicals fit into a Protestant seminary?

NEST will always be a place of theology and religious studies. I don’t see NEST starting a program in business. But I would like us to reflect on theologies of poverty, just economics, and corruption. These are real problems in Lebanon and the surrounding region, and more Lebanese should be equipped to address them at the spiritual level.

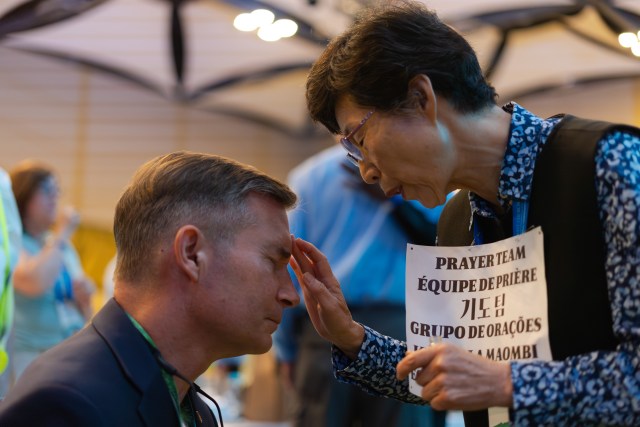

Courtesy of Near East School of Theology

Courtesy of Near East School of TheologyWe have students in our churches getting degrees in liberal arts at local universities who do not know how this education fits within a larger calling. They have grown up in the church or experienced a heart conversion as an adult, and while they want to serve God, they don’t see themselves as pastors.

Catholic and Orthodox students are similar, devoted to God in their contemplative practices but not knowing how to integrate this strength into secular life. These students should have the opportunity to take classes at NEST to think more deeply about their degrees in business, engineering, or history.

How will this integration develop?

I will have dialogues with AUB, LAU, and Haigazian about cross-registration and joint institutional credits. Though we have a shared history, many professors at these universities do not know that NEST exists.

At some point, Protestants divided university education into separate tracks for liberal arts and seminary study, as in the American Ivy League. Some of this was due to tensions between evangelism and the social gospel, which contributed to a dichotomy between mainline and evangelical churches.

But in light of God’s overarching sovereignty, it is biblical to combine them into a coherent whole so that public theology can become the life of the church. And as evangelicals seek to repair this breach—as in the Lausanne Covenant—our modern world no longer has a need for these separate paradigms.

What nags at me locally, however, is that while higher education institutions in Lebanon and the Middle East have done a wonderful job forming global citizens and experts in specific fields, they take pride when graduates become dual citizens and succeed abroad. I feel that this is a loss. I want graduates to stay here and explore their calling in their home country.

This is vocation—to make your career count in God’s perspective.

Will NEST remain a Protestant institution?

The vision I spelled out is very Protestant. It is about social transformation. There have been many different and opposing voices in our tradition about how much of our toe to dip into society, politics, and current affairs. But for me, it is theology that sets the framework for this engagement.

NEST is the only evangelical body in the Levant that belongs to the Association of Theological Institutes in the Middle East (ATIME). I hope to hire qualified Catholic and Orthodox professors. But while we will offer a broadly Christian education, other denominations will still consider us Protestant, which in our essence we will remain.

I am nonsectarian, so this is a difficult question for me. Lebanese Protestants take pride in how they have contributed to Lebanon by building hospitals and schools and in how they demonstrate an ethic of love and honest work. We aim to care for the whole person.

But these contributions no longer distinguish us from the rest of society. Nor do we want to pine for our past glories. Protestantism, for me, is about reformation, a countercurrent that improves upon what has become ineffective. It then impacts society and contributes to human well-being and the common good.

Ideally, our denominational heritage also leads to personal transformation as a disciple of Jesus. This is the church’s responsibility, and Christian involvement in society is one of the strongest testimonies to the power of Christ.

Among local evangelicals, NEST has a reputation as a liberal institution.

This is true, even within its four denominations. Some students have entered NEST excited to study and left with serious skepticism about matters of faith. My experience is that NEST has been a mixed bag of theology. It receives faculty sent by mainline partners in the West, and sometimes the vetting could have been more thorough. While many professors have been conservative, others have been quite liberal.

How are “liberal” and “conservative” defined in the Lebanese context?

Academic theologians read all the same books and think very much alike on core issues. The difference is in pedagogy—how they communicate knowledge, not the knowledge that they have.

Many professors teach as if they must communicate everything to first-year students on day one. They act as if the purpose of theological education is to give budding seminarians an electric shock, provoking an existential crisis that will hopefully lead to greater maturity. I have heard faculty members talking in the coffee room about how students are having doubts in their faith, as if this is something to be proud of.

Pedagogy should be about helping people grow and mature, to make them better citizens and Christian leaders. It is a process of walking alongside someone.

But neither is conservative indoctrination the point.

Over the years, evangelicals have started other seminaries in response to NEST, which were then critiqued similarly. On the whole, it is impossible to do serious theology for very long without the risk of being viewed as too liberal by local churches, unless an institution works very hard to stay connected to them.

Pedagogy is important, but so is content.

No one theological position has categorized NEST, which is not problematic in itself. But when one is hiring professors who do not all come from a single confessional background, an agreed-upon framework is necessary to ensure consistency in the formation of students.

I want to recruit faculty members who fit within our classical Reformed heritage. We believe in the Nicene doctrines of Jesus’ divinity, virgin birth, physical resurrection, and second coming. Concerning the authority of Scripture, Lebanese Protestants are quite conservative but sometimes too literalist.

NEST has an open evangelical position in terms of how to interpret literary genres, keeping some questions unanswered—for example, understanding the violence of God in the Bible. Women’s ordination is a matter where the mainline denominations here have made more progress than the more conservative streams of evangelicalism.

I’m excited about this side of NEST, which it pioneered in the Middle East.

On other issues, such as gender and sexual orientation, we all still have quite conservative views that reflect our conservative social boundaries. We must honor our church community with great sensitivity and with a faithful biblical hermeneutic. But we also need to better familiarize ourselves with all sides of current social and scientific research rather than rallying for any specific interpretation of a cultural cause.

How do you fit personally into the evangelical church community?

Within the mainline Protestant churches of Lebanon, I am viewed as quite conservative. Among Baptists I’ve been perceived—unjustly I would say—as too liberal. These communities are more alike than different, with much overlap in their Venn diagrams. But I won’t be an “odd fish” at NEST.

Those who are considered liberal Protestants in the Middle East are more akin to the conservative-leaning mainline churches in America. I am more concerned about NEST’s pedagogical framework than about its position on the conservative-liberal spectrum. For me, it is most important to determine how to help students get to an understanding that builds their faith and their ability to be pastors and leaders who serve their communities.

One wing of the Middle East church is said to be ecumenical, the other evangelistic. Is this fair?

These are characterizations. Mainline Protestants here care about witnessing to Jesus. Not everyone will actually evangelize, just as not every Baptist will. And the traditional evangelical approach of trying to convert everyone who “doesn’t look like me” is becoming increasingly less common.

It disturbs me when someone says, “I met this priest or monk, and I preached the gospel to him.” What arrogance toward someone who is dedicated to God’s calling. The nonecumenical approach is disastrous. Christian maturity is to preach the gospel in a way that introduces people to Jesus while journeying with them—not simply winning converts to one’s own tradition.

How will you implement this spirit at NEST?

I look for three things when searching for a church: vibrant worship, biblical teaching, and outreach in the community. A seminary should not be different.

Intellectual learning is dry; this becomes problematic if not accompanied by a life of worship, prayer, and application. Solid biblical theology is born not from discussion over what is conservative or liberal but by a devotional practice that feeds into transformation of the community.

If worship and witness result from theology, then it is a theology that works, protected from the two extremes.