There were lots of tears at the Global Methodist Church’s first General Conference, held this week in San José, Costa Rica, to officially found the new denomination. They were tears of joy, relief, and gratitude for the holy love of God.

“I cried,” said Jeff Kelley, pastor of a Global Methodist church in McCook, Nebraska. “I haven’t cried in worship in a long time. And then we had worship the next day, and I cried again.”

John Weston, pastor of a Silverdale, Washington, church and one of 21 candidates to serve as an interim bishop during the denomination’s formation period, said he felt like he couldn’t stop crying. And Emily Allen, an Asbury Theological Seminary student serving as a delegate for churches in the Northeast, wept in worship too.

“The times of worship every day have prepared us to be the church we need to be,” Allen said. “To hear the Word of God declared very boldly, to hear the invitation to receive the Spirit, to receive the holy love of God? I was just kneeling and crying.”

Many of the more than 300 delegates and 600 alternates and observers from 33 countries remembered there had been tears in past years at past conferences too. The internal strife in the United Methodist Church and the ongoing quarrels over basic theological issues, including human sexuality, the authority of Scripture, and the responsibilities of bishops, had often emotionally wrecked them. In Costa Rica, establishing a separate Methodist denomination, the tears were different.

“There’s a different spirit—it’s like a square and a circle,” said Steve Beard, editor in chief of Good News, the leading evangelical Methodist magazine. “There are disagreements here, but they are respectful, and you don’t have the automatic categorization and dismissal. They’re crying about Jesus and the Holy Spirit. Let it roll! That’s old-time Methodism.”

The newest “old-time” church met for five days at a convention center to modify and ratify the decisions of the Transitional Leadership Council, which was organized in 2022. Delegates debated educational requirements for clergy, regional representation on committees, and the exact shape of the episcopacy.

They considered a proposed constitution, debated amendments, as well as amendments to amendments, and then passed their constitution on September 24 by a vote of 323–2. People cheered—and then sat silent, a little stunned, struck by awe at the significance of what they had done—before rising to sing “Great Is Thy Faithfulness.”

“We’re doing a new thing,” said Yassir A. Kori, a Global Methodist from Sudan who works with refugees in Oklahoma. “It’s full of the Spirit, and grace, and sanctification.”

The new church is made up of 4,733 congregations at the time of formation, putting it in the top 20 denominations in the United States. It is larger, counting by congregations, than the Presbyterian Church in America, the Anglican Church in North America, and the Association of Free Will Baptists combined.

The Global Methodists have organized 36 regional groups, called annual conferences, including 16 outside of the United States. Keith Boyette, the retiring leader of the transitional church, announced the Global Methodist Church has also been legally recognized in six more countries, paving the way for additional annual conferences.

A number of bishops from independent Methodist groups outside the US attended the convening General Conference as guests and witnesses.

Ricardo Pereira Díaz, leader of a group of 580 congregations and 120 mission churches in Cuba, said he doesn’t expect his church to join the Global Methodists.

“We have a friendship without commitment,” he said. “They believe in the Bible. They believe in evangelization. They believe in sanctification. We are in sync.”

The independent Methodist church in Costa Rica, which hosted the General Conference, is not expected to formally join either. But the Global Methodists signed a cooperative agreement with the Iglesia Evangélica Metodista de Costa Rica as one of its first official acts of business.

On the other hand, Eduard Khegay, the Moscow-based bishop of 80 congregations in Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, said his group will vote on joining the Global Methodists in April.

“It’s the orthodox Wesleyan faith,” Khegay said. “They have the same heart for evangelism and mission that we do. My desire is to join, but we have to vote.”

While the majority of the church is currently in America, a lot of diversity was on display at the conference. Delegates spoke French, Spanish, Korean, and Swahili, in addition to English, with real-time translation done by artificial intelligence and a support team of human translators. A group of 29 delegates from the Democratic Republic of the Congo were not able to get visas to travel to Costa Rica, so the Global Methodists paid for them to go to a hotel with fast, secure internet so they could participate remotely. The delegates joined by Zoom, unmuted themselves to speak for and against a number of motions, and voted online.

The Global Methodists are planning to have their next General Conference in Africa in 2026, though arrangements have not all been finalized.

“When we say ‘global,’ that’s not just a nod, that’s our DNA,” said Suzanne Nicholson, Asbury University New Testament professor. “We’re not meeting in the US, and that says something. It says this really is a global church and the conference is a picture of Revelation 7, with people from every nation, tribe, people, and language before the throne and before the Lamb.”

Many of the Methodists gathered in Costa Rica said, however, that they were struck less by the diversity of the convening conference than its unity.

“When you read in Acts about the unity of the church, this is what you think it’s supposed to feel like,” said Victoria Campbell, a minister from Katy, Texas.

Johnwesley Yohanna, a bishop from Nigeria, agreed. “There is love and joy, and we praise God and are free,” he said. “There is no misbehaving, no fighting, no shouting.”

That’s not to say there were no disagreements. Debates in Costa Rica occasionally got tense, with voices rising.

A proposed amendment regulating committee assignments, intended to force regional diversity, prompted multiple people to protest they didn’t want to be “handcuffed” by a denomination that didn’t trust them to make good decisions. Discussion of ministers’ rights to trial in an ecclesiastical court brought out anguished references to “the situation in a previous denomination.” And delegates expressed strong feelings about the roles and responsibilities of bishops.

Matthew Sichel, a deacon from Manchester, Maryland, said that after years of conflict in the United Methodist Church, he was struggling to unlearn the habit of fighting.

“Each year at the annual conference, I was there to stand for orthodoxy. That was my job. We were having arguments about whether Jesus is Lord. We learned to fight. We had to. I’d go to the microphone to fight. It’s hard to let go of that,” he said.

Zawdie “Doc” Abiade, a pastor in Muskegon, Michigan, and a Christian counselor, said some of the delegates displayed signs of post-traumatic stress and there is still a lot of need for healing.

“The unhealthy comes out in displaced anger,” Abiade said. “The question is, how do we find Christ in trauma? We’re often told to forget, but we’re not designed as humans to forget. My counsel is not to run from it but face it with Jesus. Go back to the hurt and find Jesus.”

The Methodists frequently reminded each other over the five days that they are still being sanctified. They are not yet perfected, but the Holy Spirit is stronger than sin and still at work in them.

And their denomination is just getting started too. Things can change, they said to each other, and will change, getting worked out in committee meetings, ministry, and future General Conferences.

“[Decisions] are up to the church but we must make room for the possibility of adjusting tomorrow,” said Sunday Onuoha, a Nigerian bishop. “We trust their will be discernment. We make decisions and know the Holy Spirit is at work—but it’s a work in progress, not a work accomplished.”

Some of the decisions made at the General Conference were explicitly put forward as temporary measures. The church decided to elect six interim bishops, in addition to the two already in place, to serve two-year terms. At the gathering in 2026, the Global Methodists will transition to a more permanent episcopal structure, with bishops responsible for teaching and spiritual leadership—but not day-to-day administration—consecrated for six-year terms, with a two-term limit.

One of the big debates in Costa Rica was over the process for nominating the interim bishops and whether or not those people could be reelected in two years. The explicitly temporary measures, in some cases, caused more anxiety than long-term decisions.

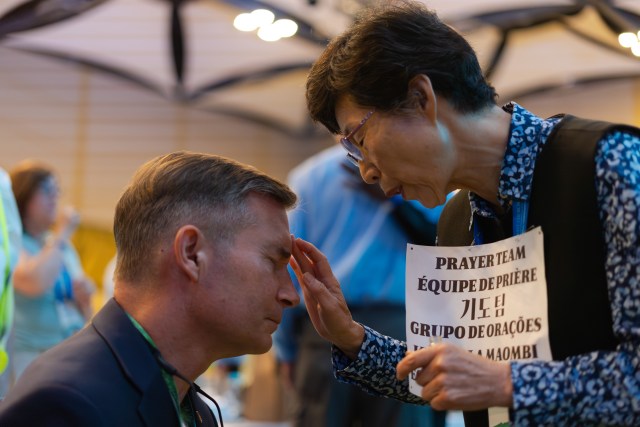

As those discussions happened, Methodists from around the world paced in the back of the convention hall, praying over everything. One man read promises from Scripture, kneeling at a chair in a corner. Others raised their hands and whispered prayers, the hiss of the word Jesus just audible in the back of the room.

“Jesus be our stage director,” prayed Hui Angie Vertz, a Korean American minister at a church in Hazen, North Dakota. “We aren’t here to direct you in our play. It’s your play, Jesus. Holy Spirit direct us.”

Before major votes, the Methodists took time to pray as a group. After big decisions, they burst into song. When they elected their interim bishops on September 25, the room of nearly 1,000 people stood up and sang the Doxology a cappella:

Praise God from whom all blessings flow

Praise him all creatures here below

Praise him above ye heavenly host

Praise Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

Sally Jenkins, a pastor’s wife from Sidney, Nebraska, said it felt like coming home after a long time away. The singing gave her goose bumps.

“We are a people who exude love for the Lord in our music,” she said. “To have the Spirit move—there are so many emotions and tears, it just does something to you, you know?”