The Stoic philosopher Seneca once wrote of the gladiatorial games in Rome, “Unhappy that I am, how have I deserved that I must look on such a scene as this? Do not, my Lucilius, attend the games, I pray you. Either you will be corrupted by the multitude, or, if you show disgust, be hated by them. So stay away.”

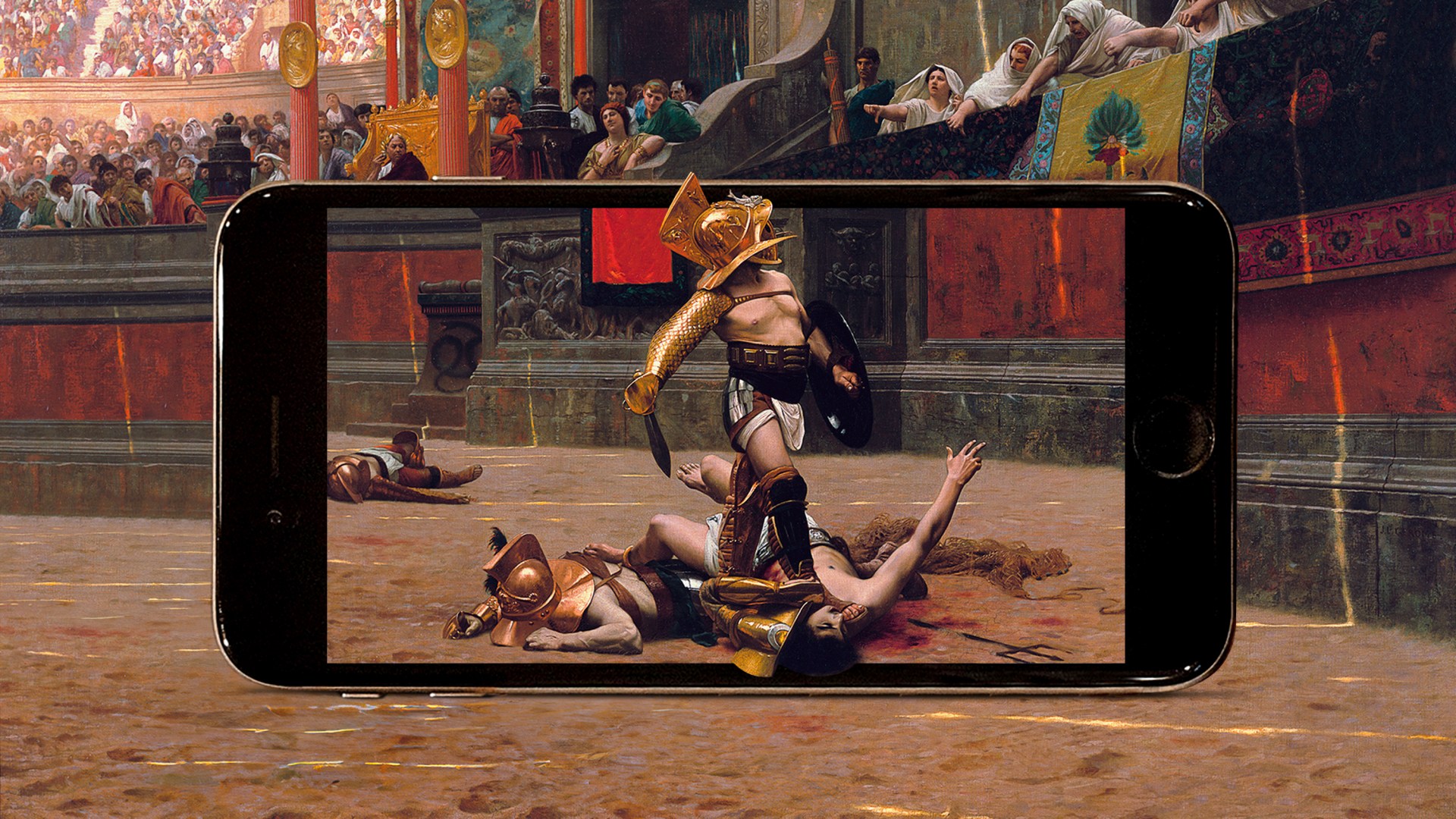

Technology has afforded us many innovative tools in recent decades. But it has also created a new amphitheater that beckons us through culture wars, politics, and election cycles. This digital spectacle hosts all things immoral and illegal—radical groups, bots with immense power, outrage entrepreneurs, and a flood of misinformation. And we clamor for the show. Seneca’s “multitude” is an omnipresent legion, and its gate of entry is in our pockets.

The ancient vice akrasia is a lazy inclination toward base desires that we know are bad for the soul. Among other woes, Jesus blasted the pharisees for their akrasia and hypocrisy (Matt. 23:25). Akrasia is prominent today in the digital spaces: We know better than to scroll and click, to trust the algorithms, to believe everything.

But we are too lazy to turn off the flood of information. We love it too much. The online world with its cultural and political drama is the new amphitheater, and our akrasia is leading to consequences beyond entertainment.

One of these consequences is that our world is shifting toward extremes as politics, celebrities, and ideological groups—from Islamic jihadists to leftist anarchist movements to militaristic white nationalist groups—shape us online toward hostility and violence.

The online mob has the ability to sort us and shape us. Digital platforms profit from algorithms that serve up stimuli making us fearful or anxious. Screens warp our conception of reality: everything is performed, cropped, and filtered. Media outlets and political parties shape reality according to alluring but reductive dualisms, false gospels that proffer empty redemption.

A repeated liturgy molds us and curates our heart one email, post, or news headline at a time, and we can’t look away. We are growing cold toward other human beings and being pulled toward radicalization.

Even politicians now are using synthetic media and deepfake audio, images, and videos: all stunningly real compilations of things that never happened. Once primarily the purview of the porn industry, now some bad actors use artificial intelligence tools to target public opinion and elections and stir general chaos. Domestic disinformation accounts propagate an increasing amount of junk and conspiracies, deliberately flooding digital spaces with material designed to overwhelm and create confusion.

Lest we blame everything on bad actors, these systems work so effectively because of our psychology, vices, sociology, and desires. Technology serves us what we want. Human systems are extensions of our collective heart, which cannot be trusted and is inclined toward evil. Algorithms and their masters amplify the dissatisfaction and clamoring of our souls. Indulging, we ignore cognitive bias and the inherent dangers of a polluted space, letting the amphitheater shape us.

Seneca was not alone in avoiding the spectacle. In the early years of the church, Tertullian wrote from Carthage in AD 200 on the ethics of Christians attending the “games.” Tertullian’s treatise De Spectaculis (“On the Spectacles”) implores Christians not to attend because the spectacles were steeped in idolatry and elicited powerful “mass emotions” toward violence and bloodlust.

Tertullian dissuaded Christians because the games had an insidious, indoctrinating effect that would push them into the ways of Rome. After all, he implored, if something is not permissible to say or to do, why would we listen to or watch it? The coliseum was where demons lurked, Christians were executed (like Perpetua and Felicity in Carthage), and temptations were celebrated. There—under the guise of entertainment—power, might, and violence were elevated. The amphitheater was a place of anti-God worship.

Our amphitheater feeds and amplifies cultural lusts, hostility, and vice. It cultivates desires and directs worship. At the amphitheater in the ancient world, you might have seen friends or enjoyed play-acting, but you also might have witnessed Christians being torn apart by lions or the guileless run through by highly trained gladiators. The results are similar in our day; the colosseum has simply modernized into a heretical online mob with AI-enabled gladiators.

Ancient philosophers encouraged enkrateia, or self-discipline, to fight the vice of akrasia. Paul wrote of this same self-control as a fruit of the Spirit, a power to proactively curates desires and affections instead of passivity. Augustine implored us to turn our restless hearts toward the Creator. Tertullian encouraged Christians to think about the greater “spectacle” of the Second Coming, the New Jerusalem and the Last Judgement.

For Christians, who are called to emulate Christ’s virtues, to spend their mental energy on “whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable—if anything is excellent or praiseworthy” and “think about such things” (Phil. 4:8), the old amphitheater and our current spectacle is not just counterproductive; it malforms.

The earliest Christians avoided the amphitheater. They abhorred violence, worship of the emperor, spurious mobs, and debauchery. Instead, they cultivated an alternative community that gently protested power politics and pagan Rome and patiently bore witness to the coming kingdom. Ancient philosophers, early theologians, and the witness of early Christians suggest we do the same.

Scott Gustafson is a researcher with the Extreme Beliefs group at Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam and the Ambassador Warren Clark Fellow at Churches for Middle East Peace.