Jesus and the Gospel in Africa: History and Experience (Theology in Africa)

Orbis Books

124 pages

$21.94

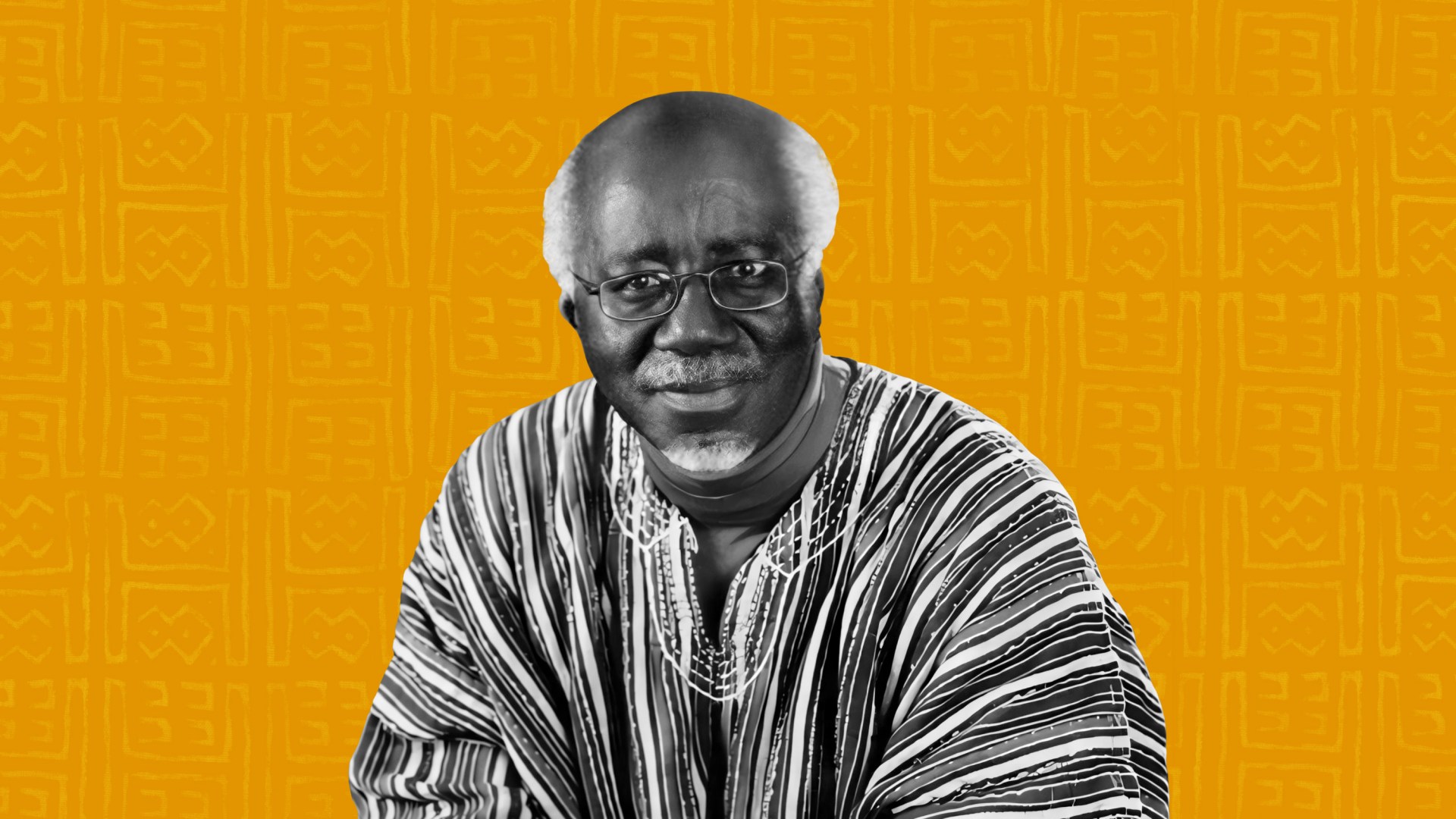

What Luther and Calvin are for evangelical Christians globally, Kwame Bediako is for many African evangelicals. From his dramatic conversion in 1970 to his death in 2008, Bediako was the primary architect of and inspiration for theological work that grappled with the realities of African culture.

On this 20th anniversary of the publication (by Orbis Books) of some of Bediako’s most influential essays in Jesus and the Gospel in Africa: History and Experience, his memory still reverberates across the continent, as indicated by the seven reflections collected below on his ongoing influence.

Born and raised in Ghana, Bediako was a professing atheist studying existentialist literature as a doctoral student in Bordeaux, France, when an awareness of Christ as the truth powerfully overwhelmed him while he was showering. He finished his degree in French literature but turned his powerful mind to the Bible and theology, later completing a second doctorate in Aberdeen, Scotland, under missiologist Andrew Walls, who called Bediako “the outstanding African theologian of his generation.”

Bediako attended the First International Congress on World Evangelization in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1974, meeting other prominent Majority World evangelicals including René Padilla, Samuel Escobar, and Vinay Samuel. At that time, he conceived the idea of a research center on the relation between the gospel and African culture. With support from his denomination, the Presbyterian Church of Ghana, that vision was realized as the Akrofi-Christaller Institute of Theology, Mission and Culture (ACI) in 1987.

While self-consciously evangelical, Bediako sought connections between the gospel and African traditional religion. He argued that the gospel’s success in Africa “shows clearly that the form of religion once held to be farthest removed from the Christian faith [i.e., African animism] had a closer relationship with it than any other.”

Bediako contended that Jesus Christ speaks to us in terms of our “human heritage.” In one of his essays, he argued eloquently from the New Testament, especially the Book of Hebrews, that Christ was our “elder brother” fulfilling the mediatorial function that African traditional religion ascribed to ancestors.

While rejecting claims of radical continuity between African religion and Christianity, Bediako also differed from the emphasis on radical discontinuity associated with Nigerian Byang Kato, first general secretary of the Association of Evangelicals in Africa. That tension between Bediako’s and Kato’s views on the interaction between the Christian faith and African culture persists today and appears in two of the reflections presented below.

Ebenezer Yaw Blasu, research fellow, Akrofi-Christaller Institute, Akropong, Ghana

I first met Kwame Bediako in 1988, when I was a Presbyterian student pastor. He was busy sorting books in what is now ACI’s Zimmerman Library. In our brief conversation, he exhorted me to ensure “Africanness” in my ministry. I listened, but without enthusiasm. At the time, my main theological inspirations were Karl Barth and John Macquarrie, who did not say anything about indigeneity in doing theology.

In 1990, I was invited to speak at an evangelistic outreach in Ottawa, Canada, on the role of Christianity in transforming indigenous cultures. Suddenly, Bediako’s earlier exhortation resonated in my mind. As if by divine intervention, I ran into him in Accra on my way to the airport. He excitedly handed me a new book he had published, Jesus in African Culture: A Ghanaian Perspective. Reading this book while in flight highly informed my message and contributed significantly to its success. For the first time, I spoke as an African evangelist outside Africa, to the glory of God.

Bediako believed that the theological education curriculum in Africa should equip Christian leaders for their task by connecting them with the redeeming, transforming activity of the living God in the African setting. If Africa is now a heartland of Christian faith, he insisted at a 1996 workshop, then “a positive affirmation of African Christianity, and not merely an African reaction against the West,” should be the driving force in curriculum development.

Kwame’s work has liberated my mind by establishing the undeniable truth that Christianity is not a “Western religion,” nor are Westerners the final arbiters of Christian theology and faith. Genuine theology needs contextual inputs, including those from indigenous or grassroots experiences. Hence, African Christianity needs to and can produce African theologies that contribute to the theological thinking of world Christianity.

Seblewengel Daniel, director, East African Sending Office, SIM, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Kwame Bediako was my PhD supervisor. His lectures were both intellectually stimulating and spiritually nourishing. He was equally committed to the deep rootedness of the Christian faith in the Scriptures and its authentic indigenous expression.

Bediako strongly advocated for a continuous engagement between gospel and culture. He asserted that people should engage their pre-Christian heritage with confidence in the power of the Spirit to guide and illuminate them. Conversion, he said, is not abandoning one’s heritage altogether and taking on a foreign identity but turning to Christ with the totality of one’s being. The divine encounter, therefore, will enable one to be an authentic African Christian.

Kwame was a charismatic preacher and teacher. The depth of his knowledge about and commitment to the church in Africa was beyond description.

Professor Bediako was very warm toward his students and had a delightful sense of humor. He took great interest in our lives and the lives of our family members. He made time to visit students in their homes, and he and his wife, Mary, invited us to their home for meals.

I value his unwavering dedication to empowering female theologians. He intentionally pursued affirmative action in his institute by appointing women to higher leadership positions.

Aiah Foday-Khabenje, former general secretary, Association of Evangelicals in Africa; country director, Children of the Nations, Freetown, Sierra Leone

Kwame Bediako’s groundbreaking work Theology and Identity framed theology in terms of self-identity as a foundation and hermeneutical tool for theological reflection. Jesus and the Gospel in Africa is a collection of articles on how Christ could be the answer to the questions Africans ask about issues relevant to their context, in contrast to the questions raised by missionary Christianity from the West. It demonstrates how God can speak to Africans in African idioms and through hearing in African mother tongues what God has done.

Bediako’s theological beliefs were inspired by his personal experience and how some church fathers practiced their faith in the context of the Greco-Roman culture. Bediako believed that it was possible for people to connect with Christ through their cultural beliefs, without the gospel having to reach Africa through Western missionaries.

One might assume that Bediako’s quest was simply about putting an African face on theology, providing Christian truth with contextually sensitive illustrations and applications. However, these aspirations for African theology were more complex and diverse than contextualization. They also involved an attempt to identify a correlation between Christianity and African culture, or between African traditional religions and the Christian worldview. This aspect of his project has raised doubts about the orthodoxy of his approach.

Diane Stinton, associate professor of world Christianity, Regent College, Vancouver, Canada

Under Bediako’s supervision of my PhD studies on contemporary African Christologies, I came to appreciate his enduring contributions to theological scholarship. He highlighted Africa’s role in Christian history, recovered the importance of primal religions to the flourishing of African Christianity, insisted on an integral identity for African Christian believers, integrated African Christianity into mainstream studies of Christian history and theology, and emphasized vernacular and informal expressions of theology.

After completing my PhD, I helped to launch a master’s degree program in African Christianity at Daystar University in Nairobi, inspired by its equivalent at ACI and graced by Bediako’s inaugural lecture in 2006.

A central conviction within Bediako’s scholarship and ministry was the tremendous significance of mother-tongue Scriptures in Africa. Against the denigration of African languages, cultures, and religions by many Western interpreters, Bediako followed his mentor Andrew Walls in seeing African Christianity as a living demonstration that the gospel is “infinitely translatable.”

Bediako exemplified what Kenneth Cragg called “integrity of conversion.” He exhibited an all-encompassing faith that gathers up “the broken fragments of our history”—a phrase from a Kenyan Anglican Communion prayer that he loved to quote—and places them before Jesus to be redeemed.

Kayle Pelletier, lecturer, South African Theological Seminary, Sandton, South Africa

As a seminary student sensing God’s call to theological education in Africa, I took a course on African traditional religion (ATR). There, I encountered Kwame Bediako for the first time. In the early 2000s, Bediako was one of the few African theologians whose work was readily accessible.

Now, after 20 years of doing theological education in Zimbabwe and South Africa, I find myself returning to Bediako to better understand why Africa remains such a syncretistic religious environment even though Christianity has been on the continent for more than a century.

Responding to derogatory Western estimations of ATR, Bediako rightly placed value on the primal religious conditions that enabled the gospel’s acceptance in Africa. Bediako sought to define an authentic African Christian identity through the African people’s pre-Christian religious experiences and beliefs. However, connecting similar, continuous elements of pre-Christian beliefs with Christian beliefs has only exchanged Western philosophical and cultural influence on Christianity for African influence, contributing to a syncretistic, tradition-accommodating gospel. Scripture, through which we must interpret any pre-religious culture imbued with general revelation, transforms belief and practice into its biblical image, creating an authentic Christian identity for all.

Nathan Chiroma, principal, Africa College of Theology, Kigali, Rwanda

As a young African theologian (originally from Nigeria), I attended two of Kwame Bediako’s seminars in Ghana. He encouraged me, as a young African theologian, to cultivate in-depth theological contemplation ingrained in my African background. Through his works and life, he gave me the confidence and inventiveness with which to approach theology.

One of Bediako’s significant contributions to African theology was the concept that African Christians can practice genuine Christianity within their own cultural expressions, dispelling the myth that Christianity is solely a Western or white man’s religion. He provided me with a model for doing theology in a way that is true to the gospel and the African context, challenged me to traverse the intricacies of religion and culture from a biblical perspective, and prompted me to reassess my preconceptions about African Christianity that had been taught from a Western perspective.

Bediako profoundly influenced many African theological institutions, originally established by foreign missionaries, that taught Western concepts out of step with our African context. His writings have been instrumental in transforming schools to better align with our local perspectives. In addition to redefining the bounds of African Christianity, his dedication to contextual theology has promoted a more inclusive and representative theological debate.

Casely Essamuah, secretary, Global Christian Forum, and Ghanaian native

Before his conversion, Kwame Bediako was an atheist who had arrived at his conclusions intellectually and with such conviction that he couldn’t keep them to himself. After his conversion, he believed that an intellectual life without reference to the living God and the living Christ was futile.

Bediako pursued scholarship in a community that had prayer and worship at its center. He saw scholarship as an opportunity for service and enlarged vision, not merely to please the academy but to equip local church leaders—hence, his insistence that ACI should be located in Akropong, the heart of Presbyterianism in Ghana, and not Accra, the political and educational capital of Ghana. Furthermore, the institute also requires that all master’s and doctoral theses must have abstracts in local languages. It is no wonder that the center he initiated continues to thrive and flourish in his absence.