At 24, I was a recent Bible college graduate and married a whopping six days when I began my first ministry as a hospital chaplain. I had never seen a dead body before. I had no experience with grief. I was way out of my depth.

After I arrived, there was a brief meet and greet with the hospital staff, who handed me four beepers and began a tour of the facility. A few minutes later, one beeper flashed brightly and I soon found myself in a small room filled with unhinged, screaming people. They had just been told their mother died on the surgery table. I had no idea what to do. That is where I first met my anxiety.

The next several weeks were similar. There is nothing like sudden death, bone marrow tests, bald children, and emergency surgeries to generate anxiety. My surprise was how much it generated in me.

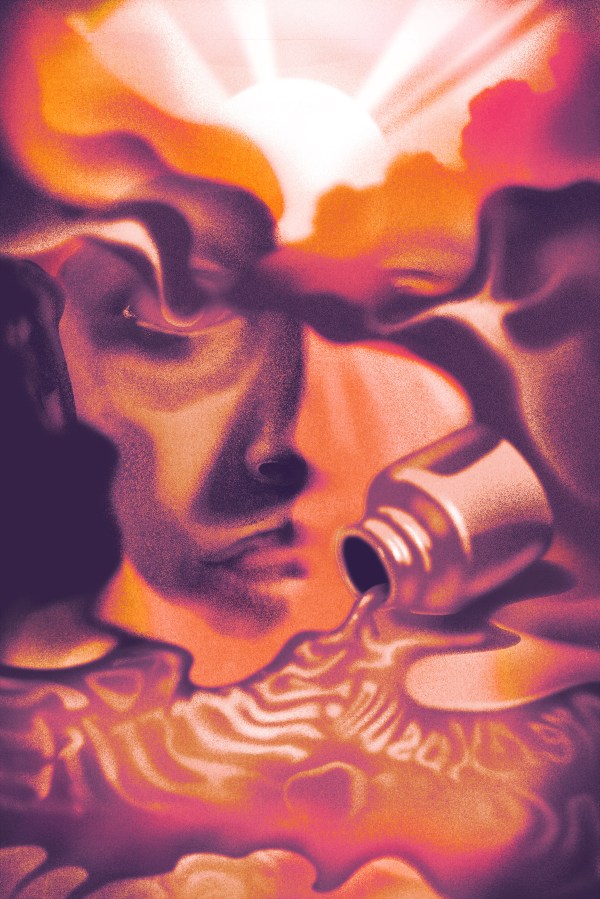

Chaplains walk into dozens of anxious rooms every day. We deeply connect to strangers in the worst and most intimate moments of their lives. We bear witness to the presence of Christ in the midst of it. How do we do it day after day without catching all the anxiety flying around? How do we not infect the room with our own? Those early weeks revealed so much unrest bubbling underneath my awareness. It infected my ability to be connected and present with God and people in their worst moments.

The year I served as a chaplain, I was introduced to systems theory, which specifically helps identify anxiety—first in ourselves and then in the people around us. I studied it further in graduate school and have been studying and teaching it ever since. I now travel the world and help leaders learn the tools to notice their own triggers, notice when they are reactive instead of connected, and notice the anxious patterns that develop in their teams.

I have come to see anxiety management as an essential path to being well. It is tricky work because most leaders are so focused on the mission at hand or on others that they struggle to locate the anxiety in themselves. They don’t naturally know when they are in its grip or when they are catching and spreading it.

After one particularly grueling shift during my chaplaincy days, the attending doctor came out of the patient’s room and said, “When someone’s heart stops beating, first take your own pulse.” You have probably heard a flight attendant say the same thing in a different way: “First put the oxygen mask on your own face before helping others.”

You cannot help another person when you are starving for oxygen in your own soul. You cannot be an effective servant for God when your own triggers and assumptions are speaking louder to you than the guidance of the Spirit.

Thus began the counterintuitive lesson of my life, a lesson I am still learning: First take my own pulse, put the oxygen mask on my own face, and connect to myself before I reach out to connect to others. It isn’t selfish; it is the fastest path to paying attention to what is really going on so I can give it to God and relax in his presence. Following this increases the chance that I will operate out of God’s steam and God’s prompting rather than my own untamed reactivity.

Well leaders know what is going on under the surface. They know how to focus on the dynamics between people as much as on the mission at hand. They can walk into rooms of high anxiety or high ambiguity and, rather than catch and spread the anxiety, relax into God’s presence. They can listen to learn rather than to defend or fix. They are clear on what is theirs to carry, what is others’ to carry, and what is God’s. (Most leaders overfunction. We carry more than God has asked us to carry.)

Well leaders know and manage their triggers before a meeting to increase their capacity to connect during the meeting. They allow themselves to be human sized instead of always trying to be superhuman. They do not need to prove themselves or appear impressive, and they manage the desire to exaggerate or showboat. They can have a difficult conversation with a critic without becoming defensive or aggressive.

When you notice you are not well, what do you do next? Many of us just press on, some right into burnout or failure. When a pastor or leader is not well and offers Jesus to someone, they can cause colossal damage in the name of Jesus.

Think of the Christian leaders in the past eight years who offered Jesus while they themselves were not well. The list is long and painful and has generated severe fallout. Do you have a personal experience with a local Christian leader who was not well while attempting to proclaim Christ? What would have been different if that leader had first taken their own pulse?

But enough about others. God invites us to take responsibility for ourselves.

I host a podcast for Christianity Today called Being Human. A feature of the podcast is when I ask each guest a series of questions called “The Gauntlet of Anxiety Questions.” As you can imagine, the title basically sells itself. One of the more popular questions on the gauntlet is “How do you know when you are not well?”

Here is another: “Who knows you are not well before you know?”

But the most provocative question about well-being isn’t on my gauntlet. It is a question Jesus asked: “Do you want to get well?”

This question has convicted me since I first read it in Scripture.

Jesus was in Jerusalem for a festival when he stopped by the famous Sheep Gate pool. The rumor was that if you could get into the pool when the water stirred, you would be healed. I’ll let John take it from here:

Here a great number of disabled people used to lie—the blind, the lame, the paralyzed. One who was there had been an invalid for thirty-eight years. When Jesus saw him lying there and learned that he had been in this condition for a long time, he asked him, “Do you want to get well?”

“Sir,” the invalid replied, “I have no one to help me into the pool when the water is stirred. While I am trying to get in, someone else goes down ahead

of me.”Then Jesus said to him, “Get up! Pick up your mat and walk.” At once the man was cured; he picked up his mat and walked. (John 5:3–9)

Notice that the man didn’t just reply, Yes, please. He bounced off Jesus’ question with a sort of excuse. I think about that a lot. Do you want to be well? Rather than saying, “Yes,” I am prone to say, “Let me explain my situation.”

It turns out my anxious leadership responses are often coping mechanisms I have used since I was a child. They have been an ever-present but insufficient help in times of trouble for decades. Even though they are unreliable, I keep leaning on them. Detangling what my anxiety calls me to do versus what God calls me to do is difficult, slow work. Though I teach people in this field full-time now, well-being is not my default experience. It takes intentionality, courage, and practice.

Do you want to be well? I hope so. We are starving for Christian leaders who take responsibility for their own well-being. Leadership is getting increasingly complex, and people are more reactive and cagier than ever, it seems. We need leaders who know how to connect deeply—to others, of course, but most importantly to God and to self.

I was surprised to learn that sometimes I had to connect to myself before connecting to God. By paying attention first to what was happening in me, I had more to bring to God, more to hand over, more to trust God with. It helped me relax into God’s presence.

Two superpowers in anxiety management are noticing and curiosity. If you can learn to notice anxiety—in you and coming at you from others—you are less likely to catch and spread it. If you can move into a posture of curiosity with yourself and others—even difficult people—you will increase your chances of being well. Here are a few questions to ask yourself:

How do I know when I am anxious?

Who knows before I know, and what are the signs?

What is mine to carry, what is theirs, what is God’s?

What do I think I need that I do not really need?

What practice that takes five minutes or less helps me relax into God’s presence?

When lately have I felt fully and completely loved?

As a person of faith, your well-being is a gift you can give the people in your spheres. They will be grateful, and it will help them be well too. But more pointedly, you are worth the effort it takes to be well. Your well-being is important to God too. I hope you can pause and relax into his presence today.

Steve Cuss is the host of CT’s podcast also called Being Human.