In the Gospel narratives, a gaggle of soldiers came to arrest Jesus before his crucifixion. Trying to stop them, the apostle Peter brandished a sword to defend Jesus from danger but missed his target, striking one of the soldiers—ironically enough—on the ear. Jesus responded by using one of his final moments in person with his followers to teach them about the dangers of political and religious violence.

Jesus rebuked Peter with a much-quoted line: “Put your sword back in its place … for all who draw the sword will die by the sword” (Matt. 26:52). Violence, Jesus taught, only begets more violence, creating a spiral that can consume individuals, movements, and sometimes even republics.

But Jesus did more than issue a policy statement. He healed the soldier who had come to do him harm (Luke 22:51).

This same soldier and his fellow combatants would continue with the arrest, and Jesus would become a victim of state-sponsored torture and death. The healing, then, was not a commentary on the soldier’s politics. Jesus did not heal because he believed the actions against him were just. The healing was a recognition of his enemy’s humanity, for there are moments to set aside politics and to see our opponents as fellow bearers of the image of God.

In the aftermath of the attempted assassination of former president Donald Trump, we find ourselves in one of those moments. Regardless of our party affiliation, it is appropriate to lament the attack, to grieve the passing of the father in the crowd who died defending his family, and to pray for all those impacted by this unjustifiable act of violence.

But for Christians, prayers are the easy part. Being honest about the state of our nation is more difficult.

It is disingenuous for us to pretend that this was unimaginable. We have seen too much death in this country to act as if anything is beyond comprehension: We have endured gunmen shooting at school children and at worshippers in churches and synagogues; at people in night clubs, grocery stores, and college campuses; and at young Black boys out for a jog. We have lost the right to pretend that it is unthinkable that someone would aim at a politician. There is a dangerous rage that has been bubbling over in every corner of this country, and, in Pennsylvania, it overflowed on the campaign trail, with tragic results.

Political violence has long been in our rhetoric as well. Our discourse on social media is a wasteland. Talk of civil war is everywhere in the background as we view fellow citizens who disagree with us as downright evil. We’ve learned to see our political rivals as an undifferentiated mass of misfits who threaten all we hold dear—as dangers to the republic.

Do not misunderstand my point. There are high stakes in politics. There are dangerous political ideas. There are some among the populace who want to undermine democracy. Policies have real-world consequences, and now is not the time to pretend otherwise.

But not every divergent opinion rises to that level. Our friends and neighbors who disagree with us are more than a collection of all the worst ideas from the other side. Yet we’ve become strangers to one another, and in our separation, discord has flourished. It is easy to denounce violence when it finally erupts; it is harder to admit that it has been all around us for quite some time, growing in the gaps made by our alienation.

It is not easy to place the beginning of the fear that I now feel for our country. I do recall a first stirring of it while watching the inauguration of former president Barack Obama in 2009. My now-teenage son was an infant at the time, but I woke him and placed him in front of the television. I wanted to be able to say that we watched the installation of our nation’s first Black president together. I was hopeful, but also afraid that he might be assassinated.

When Obama got out of the car to walk down Pennsylvania Avenue, I kept thinking, Get back in that automobile. It is not safe. That feeling of fear returned to me when I first heard the news of the attempt on Trump’s life. Things are not safe in this country and have not been for a long time. Each election has felt more fraught, divisive, and even dangerous.

Is there a path out of this deadly spiral? Yes. We must renounce the violence that endangers the entire social fabric. Jesus was correct in Gethsemane when he described hatred and murder as a social contagion that spreads from person to person. It is foolish to think that a disease that infects the rest of our lives together will not make its way to our elections. A nation that cannot protect its school-age children cannot protect its presidential candidates. A nation that cannot control its virtual rage will not control its rage in the flesh.

Words are not always violence. Violence is violence, but a “good man brings good things out of the good stored up in his heart, and an evil man brings evil things out of the evil stored up in his heart. For the mouth speaks what the heart is full of” (Luke 6:45).

We must begin to act like a people capable of holding free and clear elections rooted in principle and respectful, good-faith argument. All candidates must conduct the rest of their campaigns with an eye to restoring public trust. Every election is important, but the last few months of this particular race can set the tone for decades to come.

Trump, president Joe Biden, and any other third-party candidates should hold another debate in the coming weeks to give the United States the chance to see them present their vision for America. They should outline their actual plans for the country and make a case for why they deserve our votes. No more debates about who’s better at golf. The future of the republic is at stake.

Every American who cares about the future of democracy should vote, whether for one of these two or for a third-party candidate. A record turnout would reaffirm our commitment to the principles we hold dear. Even at this late stage, it would be a pledge to find a better way.

Peter was not the only early believer who used violence. Paul, who wrote a quarter of the New Testament, was involved in the killing of the first Christian martyr, Stephen (Acts 7). Paul’s change of heart occurred while he was on the way to arrest and jail even more of his then-opponents. His encounter with Jesus caused him to reject violence as a means of getting his way, and he spent the rest of his life traveling the Roman Empire to change lives without the aid of human weapons. He never converted a single person through the power of the sword. Instead, he made arguments. We need to make America argue with civility again, using data and reason—and love.

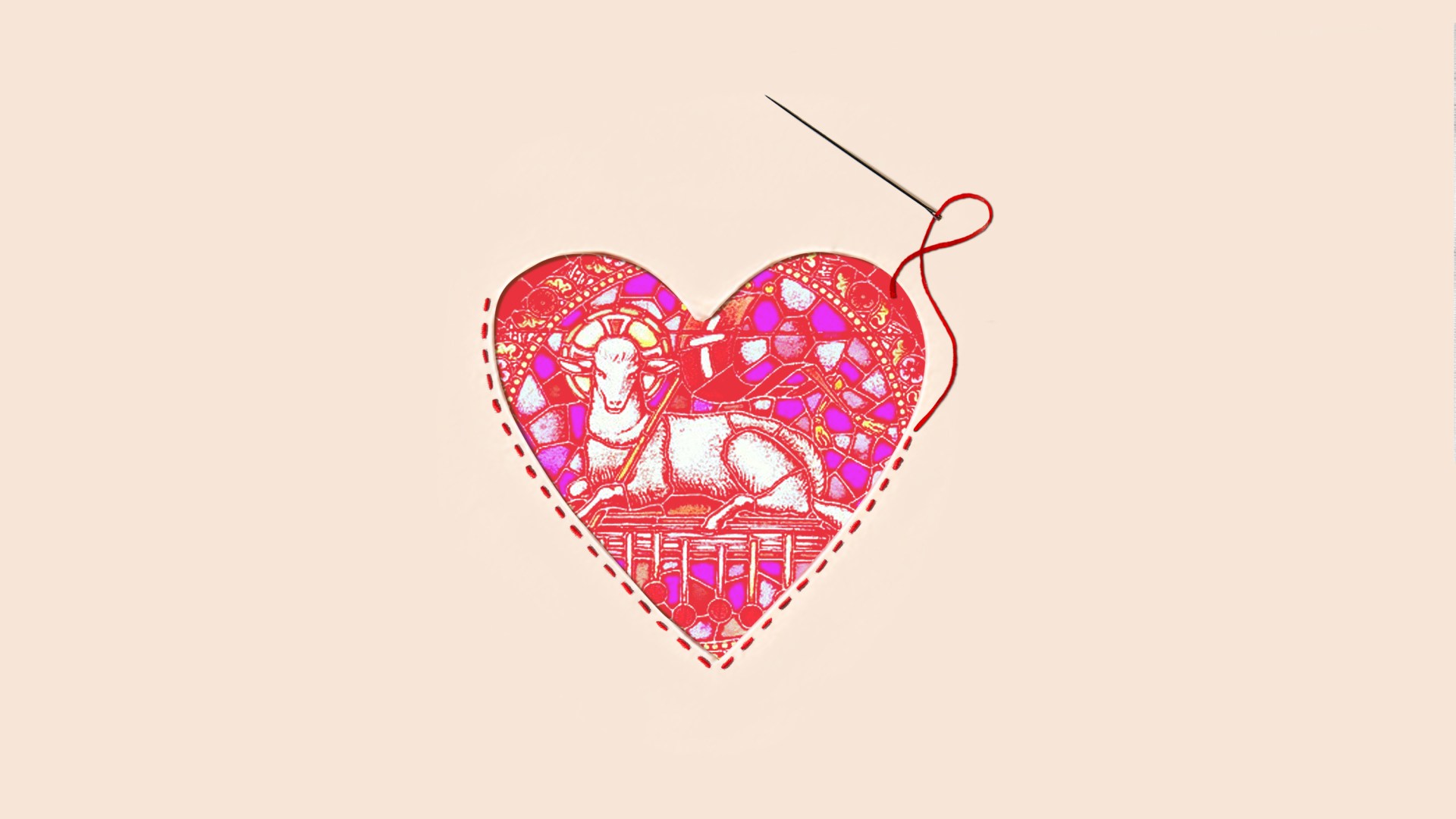

In one of Paul’s most famous passages, 1 Corinthians 13, he described love as a thing that is patient, kind, not self-seeking or boastful, not easily angered. He spoke of a love that keeps no record of wrongs. He called it the greatest of all virtues, and he had in mind the love that we might show each other as Christians (Gal. 6:10, John 13:35).

Nonetheless, love for others remains a central element of Christian teachings (Luke 10:25–37). Given the ever-rising atmosphere of hate, we would do well to recover this love as an operating principle within the church and to allow that love to spill out into the world. It might be our most important witness in this moment.

Esau McCaulley (@esaumccaulley) is the author of How Far to the Promised Land: One Black Family’s Story of Hope and Survival in the American South and the children’s book Andy Johnson and the March for Justice. He is an associate professor of New Testament and public theology at Wheaton College.