In this series

Chalolemporn Sawatsuk was a teenager in Kamphaeng Phet Province, in upper central Thailand, when he got his first tattoo.

The tattoo artist, a Buddhist monk, inked a pair of lizards onto the inside of his forearm, the same tattoo Chalolemporn’s father had. As he worked, the monk chanted blessings intended to imbue the tattoo with spiritual power that would increase Chalolemporn’s charisma and attractiveness. He also recited rules based on Buddhist moral teachings that the teen would have to follow to keep the power alive.

The tattoo seemed to take effect almost immediately, Chalolemporn said: Later that day, he convinced a woman to sleep with him.

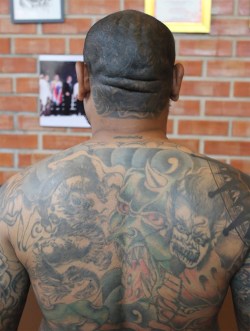

Chalolemporn later received two more spiritual tattoos. Over the years, however, the enchanted images proved ineffective in keeping his life on course. In fact, his involvement in the world of illegal drugs resulted in a sentence of life imprisonment, before his talent in martial arts won him an early release and an encounter with a Christian friend led to his life transformation.

Sak yant tattoos, which date back centuries in Southeast Asia, were initially a way to enlist the help of local animistic spirits, but they later became tied to the Hindu-Buddhist yantras, or mystical geometric patterns, used during meditation. Sak yant adherents believe the tattoos secure specific benefits, including physical or spiritual protection, popularity, or success.

The intricate designs and patterns of sak yant have become popular with Thais and foreigners looking for a cool tattoo, but Christians are concerned about their spiritual implications. Thai pastors encourage new converts with sak yant tattoos, like Chalolemporn, to recognize that God has greater power than any spirit.

“[Sak yant] is visible on their body, whereas Christians don’t worship an image representing God,” explained Thanit Lokeskrawee, director of Chiang Mai Theological Seminary. “We need to have faith … in the invisible God, which really goes against the grain of Thai people.”

Skin-deep animism

Sak is the Thai word for tattoo, while yant means yantra. Historians believe the practice is at least a thousand years old, often used to protect men in battle. Although the tattoos predate Buddhism, sak yant and other animistic beliefs were incorporated into popular expressions of the religion once it took hold in Indochina.

Sak yant tattoos include various drawings, symbols, or words often written in ancient Khmer script. Adherents believe that only tattoos done by an expert who can properly perform the required chants and rituals carry spiritual efficacy. Today, sak yant artists are usually Buddhist monks or other types of holy men.

The rules that monks tell clients to follow in order to ensure the tattoo’s continued effectiveness include some seemingly arbitrary stipulations along with moral guidance. Chalolemporn, for instance, was told not to walk under an unfinished bridge. Breaking the rules supposedly saps the talisman of its power.

After receiving a tattoo, a sak yant adherent periodically participates in ceremonies intended to re-enchant the ink on their body. Every March, about 10,000 people travel to Wat Bang Phra, a temple 30 miles from Bangkok, for a festival to honor a famous deceased monk and to receive a fresh charge of magic for their tattoos. Videos of the ceremony show devotees seeming to enter a trance-like state as they jump, scream, and charge toward the stage. Many believe they are possessed by the spirits associated with their tattoos.

Decoding Thai spiritualism

Sak yant has grown in international popularity as celebrities such as Angelina Jolie, Brooke Shields, and Ed Sheeran have obtained the tattoos. As a result of the increasing demand, more tattoo artists in Thailand are doing sak yant—sans monks or rituals.

In 2011, the Thai cultural ministry called for a ban on foreigners receiving religious tattoos out of concern that they were being placed on inappropriate parts of the body. In Thai culture, the head is considered holy, with lower areas of the body seen as progressively less so. Accordingly, a Thai may be offended by a sak yant tattoo on a tourist’s leg, since this is a less honorable location than the neck or upper back.

Many Westerners are drawn to the aesthetics of sak yant. However, they often struggle to understand the beliefs of Thais who use tattoos, amulets, and rituals to secure the assistance of spiritual forces.

Chris Flanders, a former missionary in Thailand and now professor of missions and intercultural service at Abilene Christian University, often compares the animistic spirit world to a technology his students are more familiar with: Wi-Fi.

Just as a cell phone is needed to connect to the invisible world of Wi-Fi signals, people whose worldview includes myriads of unseen spiritual beings that must be engaged or appeased must have the right device. For many Thais, Flanders said, the spiritual world is mysterious and scary yet also potentially useful—but only if people know how to tap into its power.

“Sak yant is a type of spiritual technology,” Flanders said. “It offers an opportunity to access the spiritual power that is all around us, but we’re just not aware because it’s invisible like Wi-Fi.”

Sak yant and the church

For Thai Christians, seeking spiritual protection or help through sak yant or other practices is clearly outside the bounds of their faith. Thai pastors say it’s not necessary for new believers to remove sak yant tattoos they got before conversion, especially since tattoo removal can be a difficult, expensive, and painful process. But even if the ink remains, pastors want to help eliminate the tattoos’ spiritual mark.

“I don’t have any problem with [Christian converts still having sak yant tattoos,] as long as they understand that the power is not in sak yant,” said Natee Tanchanpongs, lead pastor at Grace City Bangkok and a former academic dean at Bangkok Bible Seminary. “The power to protect them comes from the God of the universe who created them and is able to do more than we ask or imagine.”

Thanit, the seminary director, grew up in a Buddhist family and remembers noticing male relatives’ Sak Yant tattoos during childhood. He became a Christian after meeting a Thai evangelist while studying at a university. He has seen how Thai Christians struggle to fully let go of old ways of coping with fear or feelings of helplessness.

“When life is smooth and happy, [old beliefs] will hide,” Thanit said. “But once you get struck by a crisis, this kind of belief will float up and haunt you.”

In a pastoral role, Thanit says it is important to “discredit the influence” of sak yant tattoos and help Christians view them as simply ink patterns. But even for mature Christians who came to faith years ago, this can be a continuing challenge. Thanit isn’t always sure of the best way to help.

“I need God’s wisdom,” he said. “People in the past survived harm, fights, and wars with this kind of belief, so it’s not easy [to give it up].”

A different person

For Chalolemporn, the power and love of God provided something his three sak yant tattoos never could. As a teen, he showed promise in boxing, but he started hanging out with the wrong crowd and fell into drug addiction. When he ran out of money, he began selling drugs.

One day, Chalolemporn met another drug dealer in a rice field to settle a dispute, only to find the man armed with a sawed-off shotgun. Fearing for his life, Chalolemporn attacked, gained control of the weapon, and fired. Although he had intended only to scare the adversary away, the shot killed him.

Initially, a court sentenced Chalolemporn to death for his crime. However, the king of Thailand commuted his punishment to life imprisonment. At 19, he appeared destined to spend the rest of his days in Thailand’s harsh prison system.

While incarcerated, Chalolemporn restarted his martial arts career, competing in boxing and muay thai tournaments inside the prisons. He racked up victories and eventually became a national prison system champion. This success led to his sentence being reduced, a reward granted in Thailand to well-behaved prisoners who win martial arts competitions. At age 33, he was released.

The newly freed fighter wanted to continue his boxing career, but promoters were hesitant to work with a former death row inmate. During this time, Chalolemporn talked with a Thai Christian who suggested that he pray to God about his situation. Though the Christian faith was strange and unfamiliar to him, he and his wife, Sarunya, decided to ask God to give him a chance to compete.

Within a week, Chalolemporn was invited to enter a boxing match in China. However, when he arrived, he was told that he would not be able to fight. Discouraged and doubtful, he prayed that the fight would take place.

“If you are real, let me compete,” he remembers praying. “And then when I get back to Thailand, I’ll go to church.”

After a tense wait, he was informed that the match was back on. Since that first fight, he has continued competing in and winning international boxing and muay thai championships.

After returning home, Chalolemporn followed through on his promise. Another former prisoner who had become a Christian helped him find a church. From his first day at Tawipon Church in Ayutthaya, a city 50 miles north of Bangkok, he felt something he had been missing his whole life: unconditional love. The people were not judgmental of his past sins, nor were they worried about his tattoos.

“The Christians I met at church took no notice whatsoever of my sak yant tattoos,” Chalolemporn recalled. “All the people came up to me and said, It’s okay, welcome! Everyone loves you. God loves you. You have been redeemed.”

Chalolemporn says that God changed him dramatically as he learned about his new faith. Old vices gave way to an intense desire to honor his Creator.

His tattoos are still very visible, and they have even given him his nickname in the boxing ring: Kontualai, or “tattooed one.” But his belief in their power is gone. Instead, he prays to God for help and protection.

“Becoming a Christian was a really big change for me,” Chalolemporn said. “It was like becoming a different person.”