If you look at a heat map of the last presidential election’s results, my West Texas home is fiery red. In my precinct here in Midland in 2020, former president Donald Trump beat President Joe Biden by a 72-point margin—and that made us one of the more politically diverse areas in our region.

Nearby precincts had margins as high as 92 points in Trump’s favor. In one rural precinct, 100 percent of the 36 voters chose Trump. I’d have to drive more than five hours to find a spot where Biden had a strong foothold, and on the trip, I could count on one hand the number of precincts that tipped even slightly his way.

I share all this because in these final days of the race, election anxiety is palpable and electric. Heart rates are elevated on the left and right alike, and plenty of Americans are afraid of the people in communities like mine. And no wonder—headlines shout all the ways Election Day could plunge us into full civic meltdown, especially if Trump loses, as he’s already setting the stage for a quest to reverse a result unfavorable to him.

“There’s people that are absolutely ready to take on a civil war,” a recent article warned. Given where I live, you’d expect me to know quite a few of them.

I don’t. And I think it’s important to say that out loud in these fearful and fractious days.

I’m not denying the potential for political violence, including among my impassioned neighbors. The truth is, our town had a handful of locals participate in the January 6 riots in 2021. Our most famous January 6 insurrectionist owned a flower shop at the time, a strange enough image to merit a feature in The Atlantic.

But she’s not revered as a local hero. She ran for mayor in 2019 and lost, garnering just 16 percent of the vote after being dismissed by most voting Midlanders as too “out there” and conspiracy-minded. In fact, she got so little local support after January 6 that she sold her flower shop and moved out of town. That ending might not make for a compelling article—but it does throw some cold water on the doomsaying dominating our collective storytelling right now.

I don’t know how the vote will go next week, but here’s one thing I can guarantee: Most Americans will feel unhappy, unrepresented, and unheard. I’m counting everyone who voted for the losing major-party candidate, everyone who voted third party, and everyone who was too discouraged by the choices put before us to vote at all.

Even millions who vote for the winner won’t be thrilled. Polling shows three in four Americans are part of the “exhausted majority,” those who hold dissimilar policy views but also think “our differences aren’t so great that we can’t work together.” Exhausted majority members aren’t raging partisans, and we make up a significant part of the population in every state. We’d all do well to remember that.

Last year, I met a left-leaning political organizer who was visiting Midland. At lunch, she confessed that she was surprised by how welcome and comfortable she felt in our town. I found it kind of amusing—even privately scoffed a little at how she’d so easily accepted stereotypes—until I went to California a few months later and found myself similarly taken aback by how normal everyone seemed. Hello pot, meet kettle, I thought, bemused and a little embarrassed by my own stereotyping.

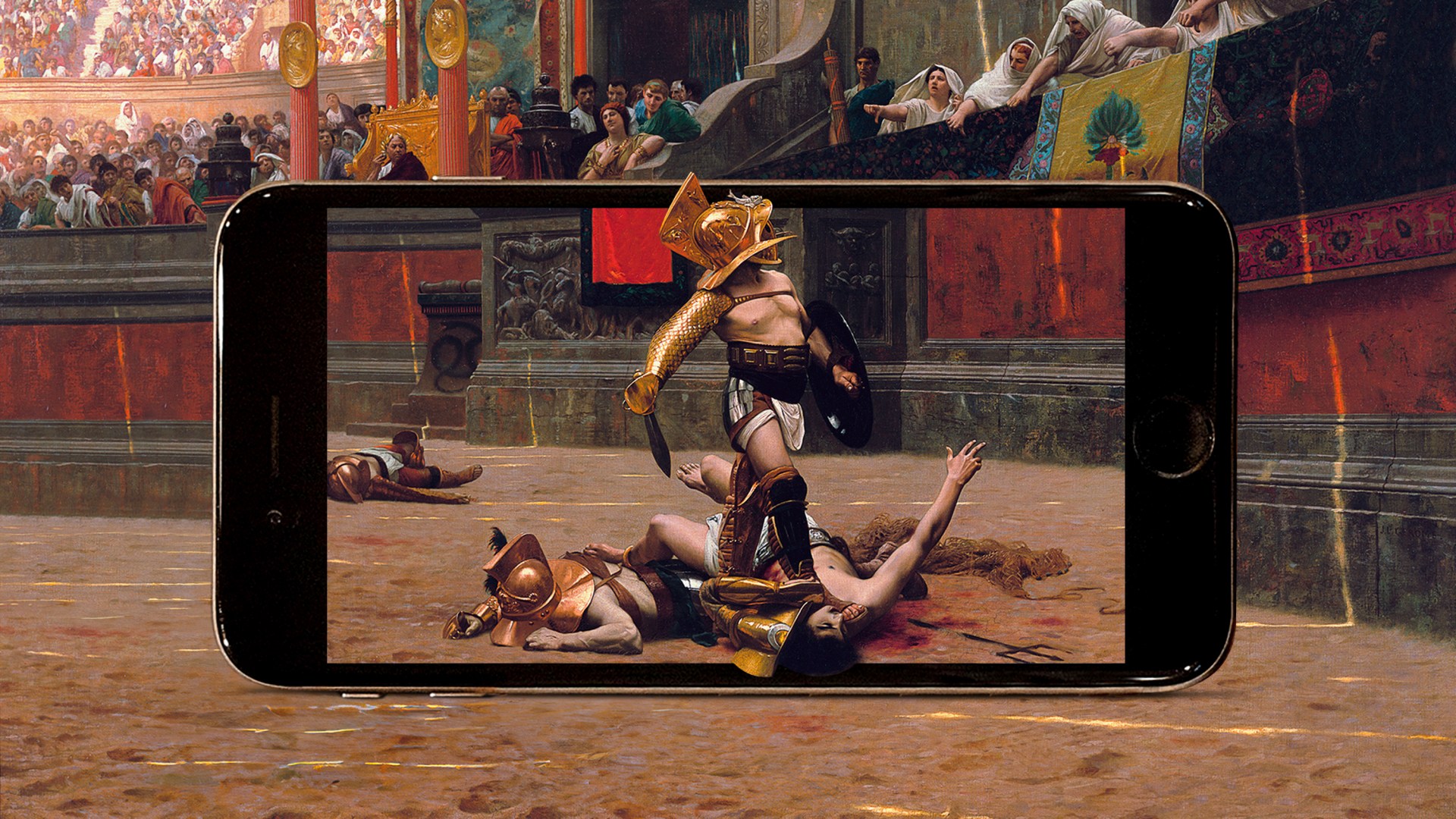

In the months since, I’ve thought a lot about why that organizer and I both thought as we did—and how that same pattern repeats every day at every level of our national discourse. We’d each taken the bait offered to us by the loudest voices on our side, which portray fringy outliers across the aisle as representative of their side.

That kind of storytelling makes for good click-through rates on social media and offers a nice ego boost, like the boastful Pharisee praying, “God, I thank you that I am not like other people—robbers, evildoers, adulterers—or even like this tax collector” (Luke 18:11). It also deceives us about the stakes in our politics, needlessly heightens tensions, rips us apart, and blinds us to our own sins.

A couple of years ago, an editor at a prominent left-leaning magazine (given the “most liberal” ranking by AllSides) reached out to me to ask if I’d be interested in writing for them. This editor sincerely wanted to seek out more diverse perspectives for his publication. He asked me to send him some article ideas.

We emailed for months on topics ranging from clean energy developments to migrants to evangelical behavior in the voting booth. Though the exchanges were always cordial, we never could come to an agreement about an angle for an article. The stories I offered didn’t confirm his prior assumptions; they wouldn’t scratch the itch for his outlet’s subscribers. Fundamentally, I think he wanted a writer who said in a different accent all the things he and his readers already thought to be true.

This is not a problem unique to the left. Last week in The Atlantic, Elaina Plott Calabro told the story of how Sylacauga, Alabama, a small town near where she grew up, captured the national media’s attention for a short time this fall due to the hordes of Haitian migrants who had come to town.

Except, when she went to find those migrants, she couldn’t. Nor could anyone else. The “hordes” turned out to be a handful of people living quiet lives and working legally at an auto plant. “But that didn’t stop people from insisting that an invasion was already under way—the lull of narrative more compelling than a desire to reckon with things as they were,” writes Calabro. Right-leaning media had all but fabricated a crisis.

Reckoning with things as they are is demonstrably less exciting than indulging in our unfair stereotypes. It’s certainly not the stuff of the campaign trail. But for Christians living in this day, it’s exactly the path we must undertake as we get through this election, regardless of who wins.

Indeed, reckoning with the way things are is a profoundly spiritual undertaking. It requires discernment. It asks us to do the hard work of recognizing where love has been driven out by fear (1 John 4:18). It requires radical honesty—confession of our fears and all the ways we’ve knotted up our trust in God’s faithfulness with the outcome of an election.

A counselor once taught me a thought experiment for when I went spinning down the path of terrible what-ifs. He’d ask me, “What if the worst does happen? What then?”

So what if the worst happens next week? What if _____ wins the election?

Well, many people won’t trust the outcome, and there might be riots or violence. It could be worse than last time. But even if that happens, it’s incredibly unlikely America would descend into the sort of chaos we see in in other parts of the world.

Still, let’s go further and say that does happen. What then?

We might lose our freedoms. My kids might not enjoy the same hope for a future that I’ve always had. Another country might become more powerful. Our country might fundamentally change its culture or governance.

I don’t think that’s where we’re headed. But Scripture tells us nations rise and fall (Job 12:23) and yet God’s Word remains (Isa. 40:8). So even if the worst does happen, what then?

Well, God’s people have lived with much less in many times and places, including right now, all around the world. It would be difficult, no doubt, and that is not the future I want for America.

But for Christians, no matter how far we follow our worst fears in this thought experiment, we will find we are always met by the tender presence of God, who promises to be our ever-present help in times of need (Ps. 46:1). As David wrote:

If I go up to the heavens, you are there;

if I make my bed in the depths, you are there.

If I rise on the wings of the dawn,

if I settle on the far side of the sea,

even there your hand will guide me,

your right hand will hold me fast.

If I say, “Surely the darkness will hide me

and the light become night around me,”

even the darkness will not be dark to you;

the night will shine like the day,

for darkness is as light to you. (Ps. 139:8–12)

This moment calls for proper perspective, not disinterested disengagement. Vote with your conscience, by all means. Pray as specifically as you feel called to pray for the outcome of the election. But as those who are allegiant first to the King of Kings, we also must ask God to reveal to us any places we’ve turned our political opponent into our spiritual enemy, trading a wild, uncontainable, not-fully-knowable God for a little wooden talisman that fits neatly in our pocket and looks remarkably like ourselves.

We must ask God to meet us in the place of our deepest fears and remind us that there is nowhere we can go to outrun his presence and no earthly ruler who can undermine his authority. Even if we live under unjust powers and principalities, God’s story carries on.

In an ancient and brief letter composed during a time of great persecution of Christians sometime between the apostles (AD 30) and the age of Constantine (AD 337), the unknown writer to Diognetus described the peculiarity of Christians. “With regard to dress, food and manner of life in general, they follow the customs of whatever city they happen to be living in, whether it is Greek or foreign,” the author said. They’re ordinary. But he continued:

They pass their days upon earth, but they are citizens of heaven. Obedient to the laws, they yet live on a level that transcends the law. Christians love all men, but all men persecute them. Condemned because they are not understood, they are put to death, but raised to life again. They live in poverty, but enrich many; they are totally destitute, but possess an abundance of everything. They suffer dishonor, but that is their glory. They are defamed, but vindicated. A blessing is their answer to abuse, deference their response to insult.

As followers of Jesus living in the United States of America, practicing both discernment and radical honesty ought to move us to a place of collective repentance. We are too far from this early description of the church. Instead of echoing the Pharisee, we should sound like the tax collector, who “beat his breast and said, ‘God, have mercy on me, a sinner’” (Luke 18:13).

No matter our politics, as followers of Jesus living in an age of contempt and despair, God may be giving us an opportunity to become peculiar again. I do not think the worst will happen, but if it does, his command for us remains the same (2 John 1:5).

A few weeks ago, I was exchanging texts with a reporter friend of mine who lives in New York City. In many ways, we come from different worlds. We often disagree politically, but our conversations are based in mutual curiosity and are always thought-provoking and civil. On that particular day, I was feeling fearful about the risk of coming unrest. “Rarely does the world come crashing down,” he texted back. “Things tend to just deteriorate until we don’t recognize or feel represented by them anymore.”

My first thought was that for many Americans, we might already be there. Plenty of people I know and love feel left behind and forgotten. And there is sadness in that, but also a strange comfort.

Regardless of what happens in this election, babies will still learn to walk. We’ll still take meals to our friends who are suffering. We’ll still assemble crews to clear rubble-strewn roads in the aftermath of devastating floods. We’ll still stand on the edge of the Grand Canyon dumbstruck with awe. It may feel like God is bringing us to our knees—and maybe that’s exactly what we need to be more faithful disciples—but somehow life carries on.

I don’t know what will happen on and after Election Day. What I do know of my red-state neighbors and blue-state friends suggests to me that the worst is far less likely than frightening headlines have led us to believe. But I also know we can be faithful followers of Jesus under any president or earthly power.

The morning after my text conversation, I woke up thinking about my reporter friend’s words in another light. What if we’ve been thinking about the wrong worst-case scenario? What if, for Christians, the worst is not political violence but the church becoming unrecognizable as ambassadors of Christ? What if we choose to pursue worldly power at the cost of our own souls? What if our witness is what slowly deteriorates until we no longer represent the one whose name we claim?

In that sense, maybe it’s true: The stakes couldn’t be higher.

Carrie McKean is a West Texas–based writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, and Texas Monthly magazine. Find her at carriemckean.com.