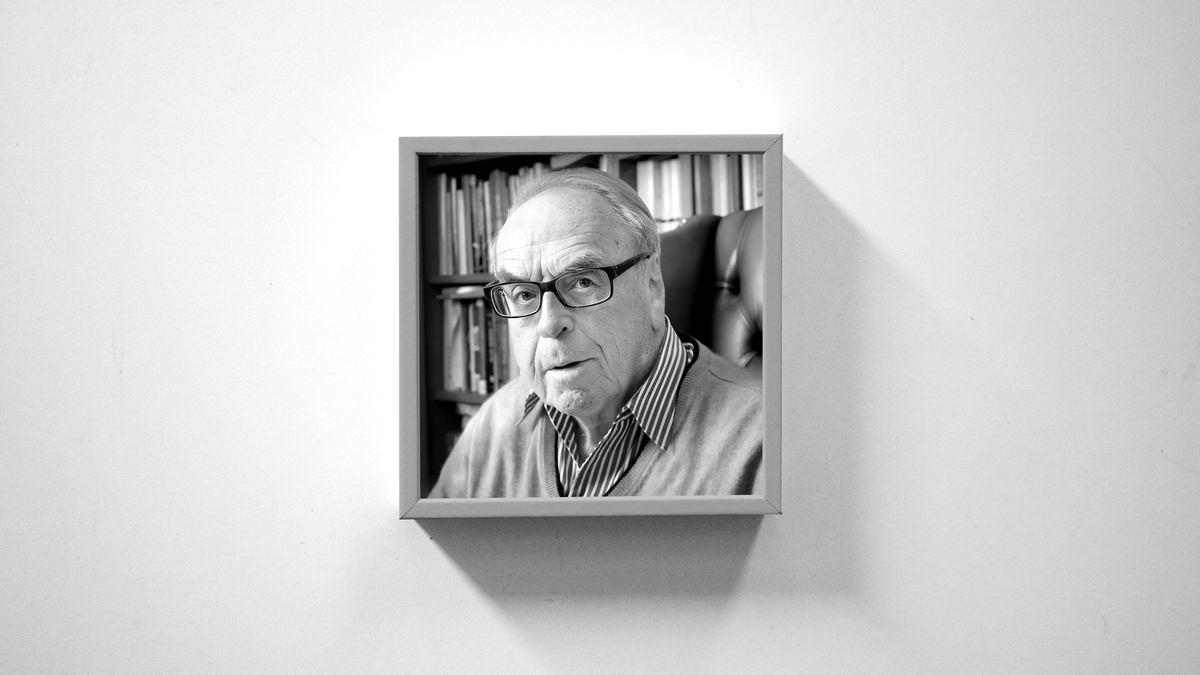

Jürgen Moltmann, a theologian who taught that Christian faith is founded in the hope of the resurrection of the crucified Christ and that the coming kingdom of God acts upon human history out of the eschatological future, died on June 3 in Tübingen, Germany. He was 98.

Moltmann is widely regarded as one of the most important theologians since World War II. According to theologian Miroslav Volf, his work was “existential and academic, pastoral and political, innovative and traditional, readable and demanding, contextual and universal,” as he showed how the central themes of Christian faith spoke to the “fundamental human experiences” of suffering.

The World Council of Churches reports that Moltmann is “the most widely read Christian theologian” of the last 80 years. Religion scholar Martin Marty said his writings “inspire an uncertain Church” and “free people from the dead hands of dead pasts.”

Moltmann was not an evangelical, but many evangelicals engaged deeply with his work. The popular Christian author Philip Yancey called Moltmann one of his heroes and said in 2005 that he had “plowed through” nearly a dozen of his books.

Editors at Christianity Today were critical of Moltmann’s theology when they first grappled with it in the 1960s but still found themselves commending his work.

“We are brought up short,” G. C. Berkouwer wrote, “and reminded to think and to preach about the future in a biblical perspective. If this happens, all the theological talks have borne good fruit.”

Today, evangelicals who are ultimately critical of Moltmann’s views—disagreeing strongly with one aspect or another—have still found much to value and frequently encourage others to read him.

“Moltmann was a constant reference point for me,” Fred Sanders, a systematic theologian at Biola University, wrote on the social platform X. “Last year I taught a little bit from his book The Crucified God, and was struck by how powerful his voice still is for students. … And even for me, on the far side of abiding disagreements, re-reading Moltmann means encountering line after line of arresting ways of putting things.”

New Testament professor Wesley Hill said he disagreed with Moltmann “on what feels like every major Christian doctrine.” And yet “few theologians have moved and provoked and inspired me in the way he has. His work is all about the crucified and risen Jesus.”

Moltmann was born into a nonreligious family on April 8, 1926. His parents, he wrote in his autobiography, were adherents of a “simple life” movement that was committed to “plain living and high thinking.” They made their home in a settlement of like-minded people in a rural area outside Hamburg. Instead of going to church, the Moltmanns worked in their garden on Sunday mornings.

The family nonetheless sent their son to confirmation classes at the local state church when he was old enough. It was seen as a rite of passage. Moltmann recalled learning very little about Jesus, the Bible, or the Christian life. The pastor focused his lessons on trying to prove that Jesus wasn’t Jewish but actually Phoenician, and therefore Aryan, teaching the children the antisemitic theology promoted by the Nazis.

“It was complete nonsense,” Moltmann said.

At about the same time, in another rite of passage, Moltmann was sent to the Hitler Youth. While the uniforms and anthems made him feel very patriotic, he later recalled, he was bad at marching and hated the military drills. On one camping trip, he was crammed into a tent with ten boys. The experience left him with the strong sense that he enjoyed being alone.

Despite the rampant antisemitism of the time, Moltmann’s childhood hero was Albert Einstein, who was Jewish. Moltmann wanted to go to university and study math. That dream was interrupted by World War II.

At 16, Moltmann was drafted into the air force and assigned to defend Hamburg with an 88 mm anti-aircraft flak gun. He and a schoolmate named Gerhard Schopper were stationed on a platform set up on stilts in a lake. At night, they looked at the stars and learned the constellations.

Then the British attacked. They sent 1,000 planes in July 1943 to drop explosives and incendiaries on the city, starting a firestorm that melted metal, asphalt, and glass. Anything organic—wood, fabric, flesh—was consumed by a sea of fire. Temperatures rising above 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit sucked the air out of the streets so the city sounded, according to one survivor, “like an old church organ when someone is playing all the notes at once.”

The operation—which didn’t target military installations or munitions factories but “the morale of the enemy civil population”—was codenamed “Gomorrah,” after the biblical city destroyed by God in Genesis 19. Around 40,000 people were killed.

When the attack was over, Moltmann was floating in the lake, clinging to a shattered piece of wood from his exploded gun platform. His friend Schopper was dead.

He would later describe this as his first religious experience.

“As thousands of people died in the firestorm around me,” Moltmann said, “I cried out to God for the first time: Where are you?”

He didn’t get an answer that day. But two years later, he was captured on the frontlines and sent to a prisoner of war camp in Scotland. A chaplain gave him a New Testament with Psalms and he started reading Psalm 39 every night:

Hear my prayer, Lord,

listen to my cry for help;

do not be deaf to my weeping.

He read the Gospel of Mark and found himself deeply drawn to Jesus. The crucifixion undid him.

“I didn’t find Christ. He found me,” Moltmann later said. “There, in the Scottish prisoner of war camp, in the dark pit of my soul, Jesus sought me and found me. ‘He came to seek that which was lost’ (Luke 19:10), and so he came to me.”

When he returned to Germany at 22—the country in ruins—he went to school to study theology. The Nazis were pushed out of the universities during the American-led reconstruction, including the University of Göttingen theologian Emanuel Hirsch, who would hum the Nazi national anthem between classes and once claimed that Adolf Hitler was the greatest Christian statesman in the history of the world.

At Göttingen, Moltmann studied under people who aligned with the Confessing Church and taught the theology of Karl Barth. He wrote a dissertation about a 17th-century French Calvinist, focusing on the doctrine of the perseverance of the saints.

While at school, Moltmann fell in love with another theology student, Elisabeth Wendel. They earned their doctorates together and got married in a civil ceremony in Switzerland in 1952.

After graduating, Moltmann was sent to pastor a church in a remote village in North Rhine-Westphalia. He taught a confirmation class of “50 wild boys,” and in the winter made house calls on skis. People asked him to bring herring, margarine, and other food from the store when he came.

“The first question I was asked everywhere was whether I believed in the Devil,” Moltmann later recalled. He taught people they could drive the Devil away by reciting the Nicene Creed. He wasn’t convinced they listened.

Moltmann’s second church was a challenge too. He was sent to a small village in the north of the country, near Bremen. There were rats in the basement of the parsonage, mice in the kitchen, and bats and owls in the attic. About 100 people attended church—but not all at once, and not regularly. On Sunday mornings, the young minister would wait at the window, wondering if anyone was going to be there.

He earned some respect from the farmers for his skill playing the card game Skat, though, and he learned to preach sermons that connected to people. If the older farmers rolled their eyes while he was talking, Moltmann learned, his theology had gotten too detached from their real-life concerns.

“Unless academic theology continually turns back to this theology of the people, it becomes abstract and irrelevant,” he later wrote. “l was not totally suited to be a pastor, but l was happy to have experienced the entire height and depth of human life: children and aged, men and women, healthy and sick, birth and death, etc. l would have been happy to have remained a theologian/pastor.”

In 1957, Moltmann left pastoral ministry to teach theology. He lectured on a range of topics but grew especially interested in the history of Christian hope for the kingdom of God.

At the same time, he started to engage with the work of a Marxist philosopher named Ernst Bloch. Moltmann wrote several critical reviews of Bloch’s books but found his ideas stimulating. Bloch argued life was moving dialectically toward a final utopia. In his three-volume magnum opus, Das Prinzip Hoffnung (The Principle of Hope), he made the case for revolutionary hope, claiming that Marxism was guided by a mystical impulse of anticipation for an ultimate fulfillment.

Though he was an atheist, Bloch frequently quoted Scripture. He said he was attempting to articulate the “eschatological conscience that came into the world through the Bible.”

Moltmann noted that while many theologians had written about faith and love, there was little in the Protestant tradition about hope. Theology had “let go of its own theme,” he said, and he decided to take up the task.

He started teaching on the topic first at the University of Bonn and then at the University of Tübingen, where he would spend the remainder of his career.

Moltmann published Theologie der Hoffnung (Theology of Hope) in 1964. It was met with intense interest. The book went through six printings in two years and was translated into multiple foreign languages. It appeared in English for the first time in 1967 and earned enough attention from theologians to attract the notice of The New York Times.

In a front page story in March 1968, the newspaper reported that debates over the trendy “death of God” theology had been replaced by a discussion of the 41-year-old Moltmann’s idea that God “acts upon history out of the future.” Moltmann was quoted as saying that “from first to last, and not merely in the epilogue, Christianity is eschatology.”

The newspaper marveled that this “theology of hope” was founded on belief in the resurrection, “which many other theologians now regard as a myth.”

Some critics at the time, however, worried this emphasis on eschatology overshadowed the work of Christ on the cross. They said Moltmann’s focus on final things ignored or even downplayed the importance of the crucifixion.

Moltmann came to think there was something to that criticism during a symposium on Theology of Hope at Duke University in April 1968. During one of the sessions, the theologian Harvey Cox ran into the room and shouted, “Martin Luther King has been shot.”

The gathering quickly disbanded as theologians scrambled to get home amid reports of riots across the country. But the students at Duke—who hadn’t seemed to care at all about the theology of hope—gathered for a spontaneous vigil in the school’s quad. They mourned King’s death for six days. On the last day, the white students were joined by Black students from other schools, and together they sang the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome.”

Moltmann, moved by the transformative power of suffering, started to work on his second book, Der gekreuzigte Gott (The Crucified God). It was published in 1972 and came out in English two years later.

“Christian identity can be understood only as an act of identification with the crucified Christ,” Moltmann wrote. “The ‘religion of the cross’ … does not elevate and edify in the usual sense, but scandalizes; and most of all it scandalizes one’s ‘co-religionists’ in one’s own circle. But by this scandal, it brings liberation into a world which is not free.”

Moltmann united the two ideas—Christ’s suffering and Christians’ hope—and that became the core of his theology. He taught that people should “believe in the resurrection of the crucified Christ and live in the light of his reality and future.”

Or more simply: “God weeps with us so that we may someday laugh with him.”

Moltmann retired in 1994 but continued to work with graduate students for many years after. When his wife died in 2016, he wrote a final book on death and resurrection.

Moltmann is survived by four daughters.