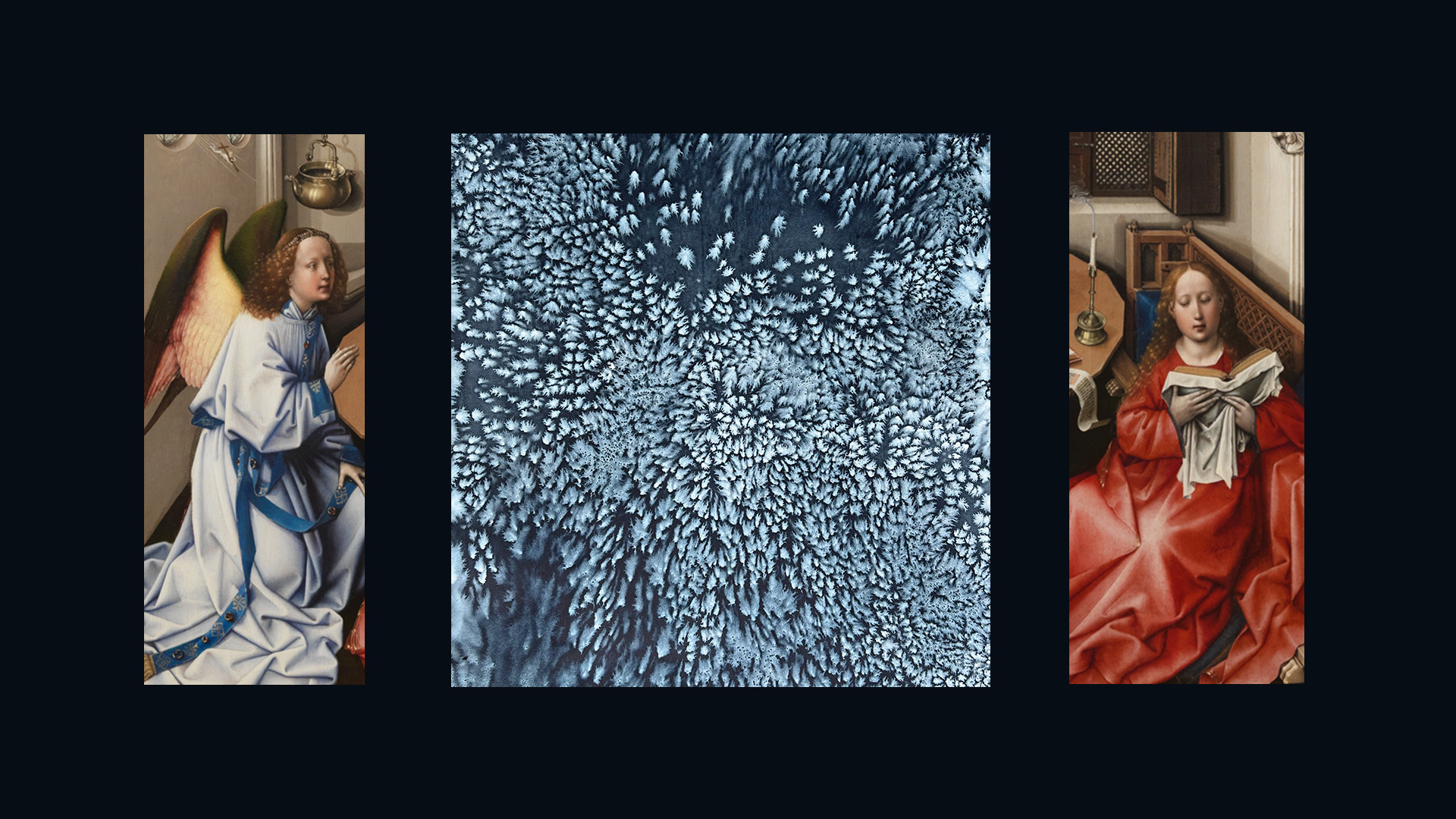

The people walking in darkness have seen a great light; on those living in the land of deep darkness a light has dawned.” This luminous verse in Isaiah 9 is traditionally read at Advent as we look forward to the coming light of Christ.

For those of us who live in the Northern Hemisphere, this passage is especially apt, as the whole celebration of Christmas in midwinter has an extra layer of meaning, a kind of parable from nature to underline and emphasize the prophecy of Isaiah.

Isaiah is speaking of the darkness of exile, the darkness of our fall, and—at the root of it all—the thick, clotted darkness of sin. This is the darkness that Christ comes to dispel, and John, perhaps remembering this verse in Isaiah, tells us that the light shines in darkness and the darkness has never overcome it (John 1:5).

To hear these readings in the dark time of the year, when the nights draw in and help us see the light more brightly, reminds us of the final triumph of the inextinguishable light of Christ—not just in our heads, but in our hearts; not just by reason, but by a kindled imagination.

When a child comes up in church to light an Advent candle, the gospel is known not only with the mind but with the body as well. And that is especially important as we celebrate the Incarnation, the astonishing truth that God became one of us, that he who is the Light of the World was once as young and vulnerable as the child who lights the candle.

As a poet, I have found myself drawn again and again to “the light within the light by which I see,” as I put it in one of my Advent sonnets. The light that shines in darkness is also an image, a living symbol, to which everyone responds.

Some time ago, I wrote a winter blessing. I wanted to frame my blessing in such a way that it could be shared, perhaps at a candlelit dinner table, with those who do not yet share our faith. I wanted to invite conversation about who the “winter child” really is. Those who do not yet share our faith can share our wonder at the beauty and comfort of light in the darkness, from the stars in the heavens to the candlelight at a service or over a shared meal.

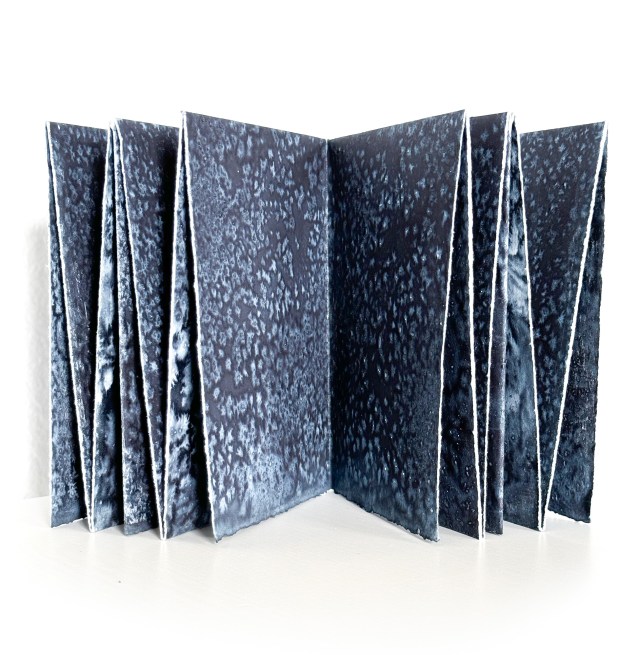

Winter Benediction

When winter comes and winds are cold and keen,

When nights are darkest, though the stars shine bright,

When life shrinks to its roots, or sleeps unseen,

Then may he bless and bring you to his light.

For he has come at last, and can be seen,

God’s love made vulnerable, tightly curled:

The Winter Child, The Saviour of The World.

Malcolm Guite is a former chaplain and life fellow at Girton College, Cambridge. He teaches and lectures widely on theology and literature.

“Winter Benediction” was originally commissioned for Cultivating magazine and published by Cultivating Oaks Press. Used with permission.