The box was a fire I could not touch.

It arrived at our house one summer evening, handed off to me by my in-laws. I stuck it in the garage, thinking that if I ignored it, it would disappear. With each passing day, it became buried under a thin layer of West Texas dust and the stuff of life—stray cups from the car, pool floats, my daughter’s viola. Months passed. Yet I could still see my father’s distinct handwriting peeking out, the thick black lines scrawled across the top in Sharpie: “GIVE TO CARRIE.”

Ten years had passed since I last spoke to my parents. But each time I walked by the box, I’d hold my breath—as though my father’s anger might bleed out of the letters of my name and back into my life.

There were things I longed to find in the box, like my treasured collection of Nancy Drew books, which I imagined arranging on my daughter’s shelves. But there was likely a darker inheritance lurking inside too, so I put off unpacking it.

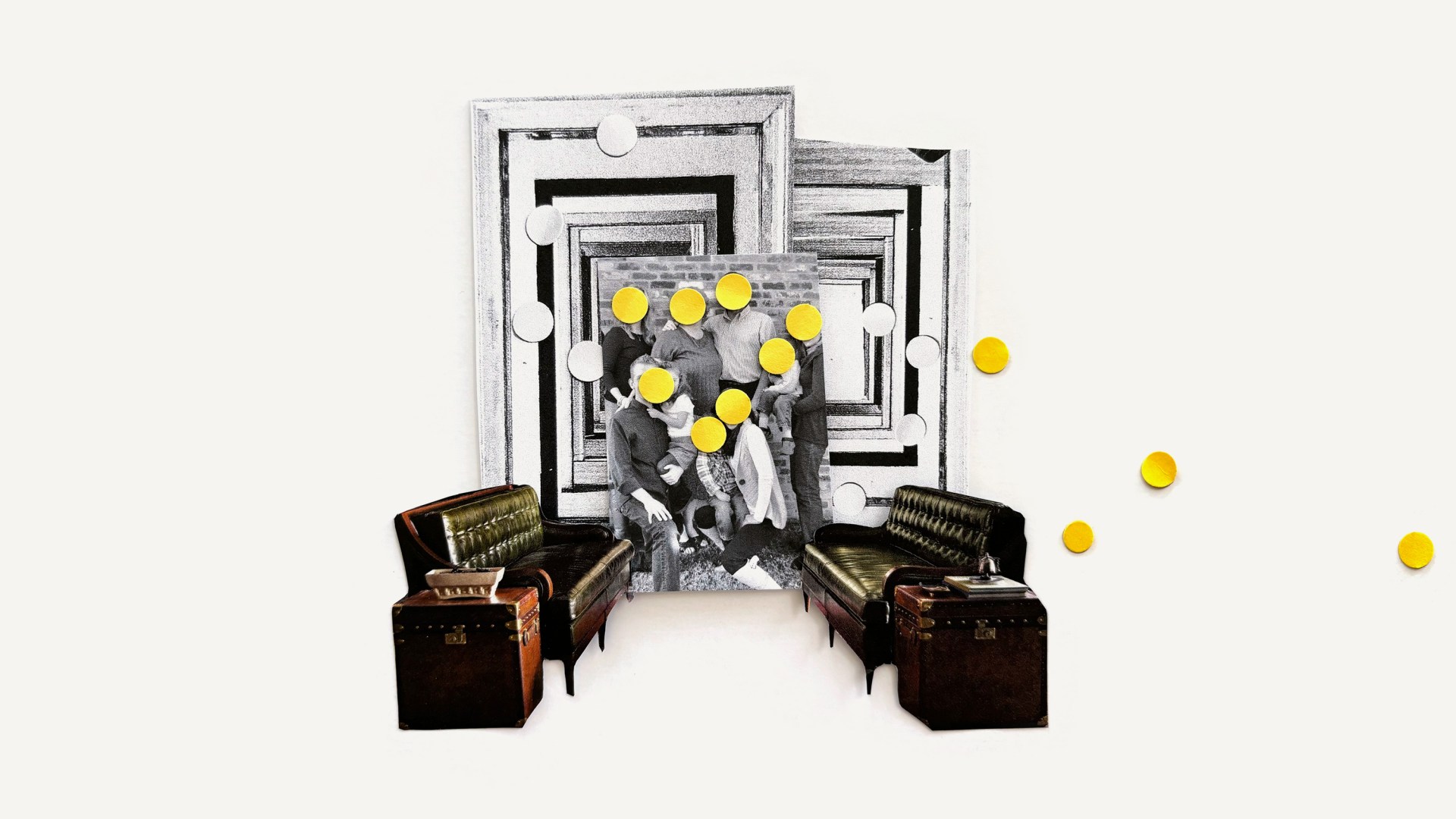

Across the US today, there are maybe 68 million boxes like mine hiding in garages—one for each of the 1 in 4 Americans who reports being estranged from a relative. The estrangement between my parents and me is the most difficult kind to reconcile: the kind rising out of trauma, abusive parenting, and mental illness in the family system.

The outside world may look at my situation and say that I had every right to walk away. Others, like my parents, think estrangement is never the answer. But I have spent more than a decade somewhere in between, asking myself how I can remain a faithful follower of Jesus while denying my parents access to my life. I am convinced that cutting off ties was my only escape hatch, but my desire to follow Jesus keeps me wrestling with persisting questions of obedience and grace.

How can I honor my father and mother if I refuse to see them? If I say I take Jesus’ teachings on forgiveness and reconciliation seriously, does being estranged mean I’m a hypocrite—bitter and unforgiving?

I am both estranged from my parents and alarmed by the casual way the topic is discussed in Western culture today.

“It’s better to become an orphan than remain a hostage” is a catch-phrase of licensed therapist Patrick Teahan, who has built a successful career around supporting those who decide to cut off their families. Going “no contact” with parents and relatives, what one New Yorker article calls “the process by which family members become strangers to one another,” is normalized in some circles.

Teahan’s advice on writing a no-contact letter epitomizes our current cultural stance toward estrangement: “Short, to the point. Don’t tell them why. ‘You’re toxic’ is all you need to say.”

Cultural observers worry that, in particular, estrangements caused by significant differences in core values, like political convictions, are experiencing an uptick. As our society grows more polarized, especially in brutal election seasons, advice like Teahan’s is becoming increasingly acceptable. But what are we left with when we cut the ties that bind?

After ten heartbreaking Thanksgivings, here’s what I have learned: Empty chairs always take up the most space. Empty chairs always shout the loudest.

One day on the social platform X, I read the story of James Merritt and his son Jonathan. By contemporary American cultural standards, there’s every reason for them to be estranged. Jonathan is a self-described “progressive gay man” living in New York City and writing about faith and culture. James is a pastor and the former president of the Southern Baptist Convention; he describes himself as “to the right of Ronald Reagan.” And yet, according to the post, the two “maintain a close relationship.” Intrigued, I messaged Jonathan, and we set up a time to talk with his father.

I learned that after Jonathan’s homosexuality was made public in 2012, forging a new relational path forward wasn’t easy for either of them. Jonathan, in particular, understood well the enticing pull to sever relationships with those with whom we disagree. Cutting off a primary relationship due to disagreements—even profound ones—might feel like it will reduce one’s emotional distress, Jonathan said, but it’s only sending conflict underground, where it “gets exported to other relationships, which start to suffer.”

Jonathan’s mentors helped him process his pain and discern that his father’s disagreements with him were not a rejection of him. Meanwhile, James refused to go after his son publicly over views opposed to his own, even when his silence made other people angry.

In spite of their differences, the two Merritts have been able to stay in relationship because they both subscribe to the same principle: It is almost impossible to love someone if you are consumed with trying to change them.

“The bottom line is this: When we stand before the Lord, each one of us is going to give an account for his own heart and his own life,” James said. “I can’t change Jonathan even if I wanted to, and vice versa is true too. … That’s God’s job.”

James and Jonathan are not cut off from each other the way I am from my parents, and talking to the father and son left me longing for my relationship to look more like theirs. But our conversation also helped me understand that the Merritts and I, estranged or not, have come to know how very little is within our control.

“Can we please clean out the garage?” my husband finally asked last fall, after we’d stepped around the box for at least six months.

So, one afternoon when the house was empty, I unpacked it. Sitting on the dusty floor, I sifted artifacts from my childhood into piles around me: pictures of first crushes, favorite teachers, and cousins at Christmas; my high school graduation cap; stuffed animals; countless trinkets whose importance had been lost to the decades.

Ten years ago, on the day of my sister-in-law’s baptism, I watched my parents walk out of the church and to their car. I didn’t know it was goodbye; I only knew I couldn’t bear to see them the next day. I never dreamed that I’d stack day upon day until I’d built a life apart from them, with little more than the contents of a box to prove I’d once lived as their daughter.

Leading up to that Sunday, I’d done everything I could to find a different way. I navigated every encounter like a game of chess, plotting three moves ahead, attempting to keep us far from the terrifying terrain of my father’s unmanaged, self-treated mental illness, with its delusions and increasing unpredictability.

I chose alcohol-free restaurants, keenly aware of how booze unleashed my alcoholic father’s poisonous tongue. I listed out safe conversation topics in advance—the weather, funny things the kids did, a recipe I tried and liked—keeping a wide berth around the minefields of politics and theology. But every encounter, at best, left my father mollified, my mother pretending all was okay, and me anxious and knotted up.

It worked until it didn’t. That Sunday afternoon, my plotting failed. I was in checkmate, clutching the hand of my toddler as I realized that no matter how I contorted myself, it was never going to be enough. Decades of manipulation and verbal abuse had proven my father had room in his life for only one version of me, fashioned in his own image, faded and blurred until I existed only as a reflection of his own thoughts and beliefs.

As I listened to a fresh round of his accusations, blame, and defensiveness, the truth settled over me with clarity: He would never stop trying to control my every thought, and I, if I remained, would never stop trying to manage our every interaction.

In the aftermath of my decision, I learned there are few people who understand that you can love someone and still walk away—and even fewer people in the church. Even my most supportive friends and family weren’t quite sure how to support me through this sort of loss. Their confusion echoed my own: Was my sadness evidence that I’d made a grave mistake?

When my parents sold and cleaned out my childhood home, they sent me the box. In the garage that afternoon, a wave of grief hit me as I neared the bottom. The Nancy Drew books weren’t there. I pictured myself, ten years old, all knees and elbows, lying on the floor of my bedroom as I disappeared into a world where mystery, fear, and uncertainty were safely resolved by the last chapter.

I reached for the final item in the box: a blue Bible with a tattered cover. See, it wasn’t all terrible, I reminded myself. I could still picture the day Brother Eddie at First Baptist Church in White Deer, Texas, placed it in my hands on the occasion of my baptism.

Was I seven or eight years old? I opened the cover to search for a date and was caught off guard by a new message, scrawled in my father’s heavy hand: “If God does call you into the kingdom in this life, you will start living the fifth commandment and repent and call your mother!”

Shame—estrangement’s close friend—rose up like bile in my throat. You are a terribly cruel daughter. And just like that, the inheritance of my life blackened, turned to ashes by my father’s words.

In the early years of my estrangement, I’d sometimes wake up at night panicked, dreaming I had lost my parents in a crowded street, an endless forest, or a stormy sea. Even now, I feel the visceral heaviness of their absence, like a phantom pain. At Christmas, I imagine my parents sitting in their home, bereft of grandchildren, our memories as an extended family permanently stunted.

But I cannot go back to the way things were. It is as simple and as infinitely complex as that. And it has taken me a long time to accept that God’s grace covers this too, for he is no stranger to messy families.

The Bible itself is full of estrangement stories. Esau, enraged by his father’s favoritism and his brother’s trickery, vows to kill Jacob (Gen. 27). Absalom, David’s favorite son, is driven into banishment (2 Sam. 13). The prodigal son, in Jesus’ well-known parable, takes his father’s wealth and disappears (Luke 15).

In other parts of the Gospels, Jesus speaks about human relationships plagued not just by rank sin and selfish ambition but by disordered loves and misplaced priorities. He tells his followers to let the dead bury their dead (Luke 9:60) and redraws the boundary lines of family around those who do his will (Matt. 12:48–50). These are difficult teachings that reiterate the importance of letting nothing come between us and Christ—not even our families or communities.

These biblical examples show that estrangement is not only a cutting off but also a letting go. One person gives up control over the actions and life choices of the other. Jacob flees; David turns away and weeps; the father hands over the inheritance and waits. And over and over again, the letting go in Scripture comes with a promise: Even when family ties are severed, God does not cut off his care.

The two ways our society tends to deal with ruptured relationships pale when we take God’s care out of the picture.

If the box in my garage is a metaphor for the process of estrangement, some people take the whole of it to the dumpster. This is the wisdom of the contemporary age: Everything is disposable and replaceable—especially people whose views rub us the wrong way—and life’s purpose is to “live your truth” with a mantra of “you do you.”

Others go to the opposite extreme. We take the whole box into the heart of our home and unpack it there. “Forgive and forget,” we tell ourselves, even while cutting our fingers on fractured vases. In many churches, people are told that the proper response to strife is either to ignore it or to reconcile at all costs. But sometimes it’s more complicated than that.

The Bible’s take on estrangement offers a third way for those of us living with severed relationships, one that neither gives in to the pull toward easy estrangement in an age of contempt nor allows the false, uneasy peace of pretending nothing is wrong.

Instead, the gospel equips us to navigate the complicated landscape of broken human relationships. It teaches us to seek biblical reconciliation with the long view in mind. Like the prodigal’s father, we learn to watch the horizon for signs of restoration and return. Like Moses, far from his Egyptian family and shunned by the Israelites, we wait in the wilderness as the unapproachable fire becomes holy ground.

In my garage that day, sitting with my defaced childhood Bible in my lap, the sharp edges of my father’s handwriting were suddenly softened by the tenderness of my heavenly Father’s voice: You are my beloved child, and you are already part of my kingdom.

It was up to God to intervene in their lives, not me. His only request for me was to let go of them and cling to his hand.

This side of Eden, human family systems can be dangerous and dishonoring. Estrangement can be a necessary step because to remain embedded in such families is a degradation of the imago Dei present in each of us. God does not delight in our suffering or our abuse.

Even less corrosive situations, like stark differences in political views, can expand into insurmountable relational rifts. Sometimes difficult choices must be made. But choose estrangement carefully, knowing its costs, only after every other avenue has been tried. Ten years on this path has taught me the road is rocky and difficult—you will not emerge without a limp.

“If it is possible, as far as it depends on you, live at peace with everyone,” the apostle Paul wrote in Romans 12:18. “As far as it depends on you” calls us to radical humility, forgiveness, and forbearance, but it also calls us to honesty.

There are relational circumstances—choices made by other fallen humans—that remain outside our influence, no matter how much we long otherwise. There are limits to how far our imperfect love can go, walls beyond which we cannot see. In such moments, Romans 12:18 makes way for us to say, “This is as far as I can go,” looking to the one who can take things from there.

Not every fraught relationship can be like James and Jonathan Merritt’s; some will end like mine. Yet even here in the wilderness of estrangement, there are valuable gifts.

In the absence of my parents, I have found Christian community that has been my surrogate family these last ten years. I have found wisdom and counsel in spiritual shepherds who have helped me discern my way forward. I have leaned on the love of my husband, friends, and extended family, who remind me of my worth even when I cannot see it myself. God has been constantly present in every big and small moment of my grief, restoring my identity in him, tenderly healing my wounds.

The enemy wants me to see my childhood Bible as a symbol of bitterness, grief, and fracturing—to wear it, and all that it represents, like a shackle around my neck. But I, like Joseph, can instead say, What was intended to harm me is being used for good (Gen. 50:20). What was meant to wound me now instead trains my eyes toward the horizon, and I long for my parents to experience the same grace.

That Bible is now on a shelf in my house—not the inheritance I imagined, but a good and beautiful one nonetheless.

Carrie McKean is a West Texas–based writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, and Texas Monthly magazine.