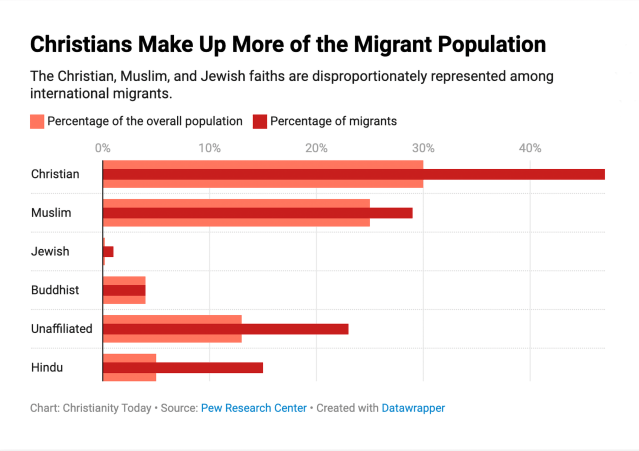

The world’s 280 million immigrants have greater shares of Christians, Muslims, and Jews than the general population, according to a new Pew Research Center study released Monday.

“You see migrants coming to places like the US, Canada, different places through Western Europe, and being more religious—and sometimes more Christian in particular—than the native-born people in those countries,” said Stephanie Kramer, the study’s lead researcher.

While Christians make up about 30 percent of the world’s population, the world’s migrants are 47 percent Christian, according to the latest data collected in 2020.

The study found that Muslims make up 29 percent of the migrant population but 25 percent of the world’s population.

Jews, only 0.2 percent of the world’s population but 1 percent of migrants, are by far the most likely religious group to have migrated, with 20 percent of Jews worldwide living outside their country of birth compared to just 6 percent of Christians and 4 percent of Muslims.

Four percent of migrants are Buddhist, matching the general population, and 5 percent are Hindu, compared to 15 percent of the world population.

Over the past 30 years, migration has outpaced global population growth by 83 percent, according to Pew.

Though people immigrate for many reasons, including economic opportunity, to reunite with family, and to flee violence or persecution, religion and migration are often closely connected, the report finds. US migrants are much more likely to have a religious identity than the American-born population in general.

The influx of religious migrants can have a significant impact on the religious composition of their destination countries. In the case of the US, “immigrants are kind of putting the brakes on secularization,” Kramer said.

While about 30 percent of individuals in the US overall identify as atheist, agnostic, or religiously unaffiliated, only 10 percent of migrants to the US identify with those categories.

Pew studied data from 270 censuses and surveys, estimating the religious composition of migrants from 95,696 combinations of 232 origin and destination countries and territories.

Their analysis focused on the “stock,” the total number of people residing as international migrants, rather than “flows,” numbers measured over a specific time. This methodology allowed them to study all adults and children who live outside their countries of birth, regardless of when they immigrated.

“We’re not only interested in the religious composition of people who arrived in a destination country in the last year or in the last five years,” explained Kramer. According to the report, measuring the total “stock” of migrants reflects slower changes, “patterns that have accumulated over time.”

The study found that migrants frequently move to countries where their religious identity is already represented and prevalent. For example, Israel is the top destination for Jews, with 51 percent of Jewish migrants (1.5 million) residing there, while Saudi Arabia is the top destination for Muslims, with 13 percent (10.8 million) residing in the area.

Christians and religiously unaffiliated migrants share the US, Germany, and Russia as their top three destinations.

The majority of the world’s Christian migrants originate from Mexico and settle in the US, Pew found. They are typically looking for jobs, improved safety, or to reunite with family members. Meanwhile, 10 percent of the world’s Muslim migrants (8.1 million) were born in Syria, fleeing regional conflict after a war broke out in 2011.

The report attributes high rates of Jewish migration partly to Israel’s Law of Return, which grants Jews the right to receive automatic citizenship and make aliyah, a move to Israel.

As of 2020, about 1.5 million Jews born outside of Israel now live within the country’s borders. Jewish migrants to Israel often come from former Soviet republics, such as Ukraine (170,000) and Russia (150,000). The United States has the second highest population of Jewish migrants (400,000), with a quarter moving from Israel.

Across the board, however, Kramer said that immigration levels across religious groups have remained fairly stable over time. Despite consistent numbers, she advocated for doing this study because of the popularity of a 2012 Pew report, Faith on the Move. The two studies used different methodologies, and Kramer described Faith on the Move as a “snapshot” of religion and immigration in 2010.

“A lot of people have asked for an update to it, and we get a lot of questions related to religion and migration,” she said. Despite demand for the data, “Faith on the Move was really the last report we put out that focused on this.”

Many of the findings in the new report are similar to the 2012 study, and Kramer found the results relatively unsurprising.

“Even in that older data, you can see that religious minorities were so much more likely to leave their country of origin and migrate to a country where their religious identity was more prevalent,” she said.