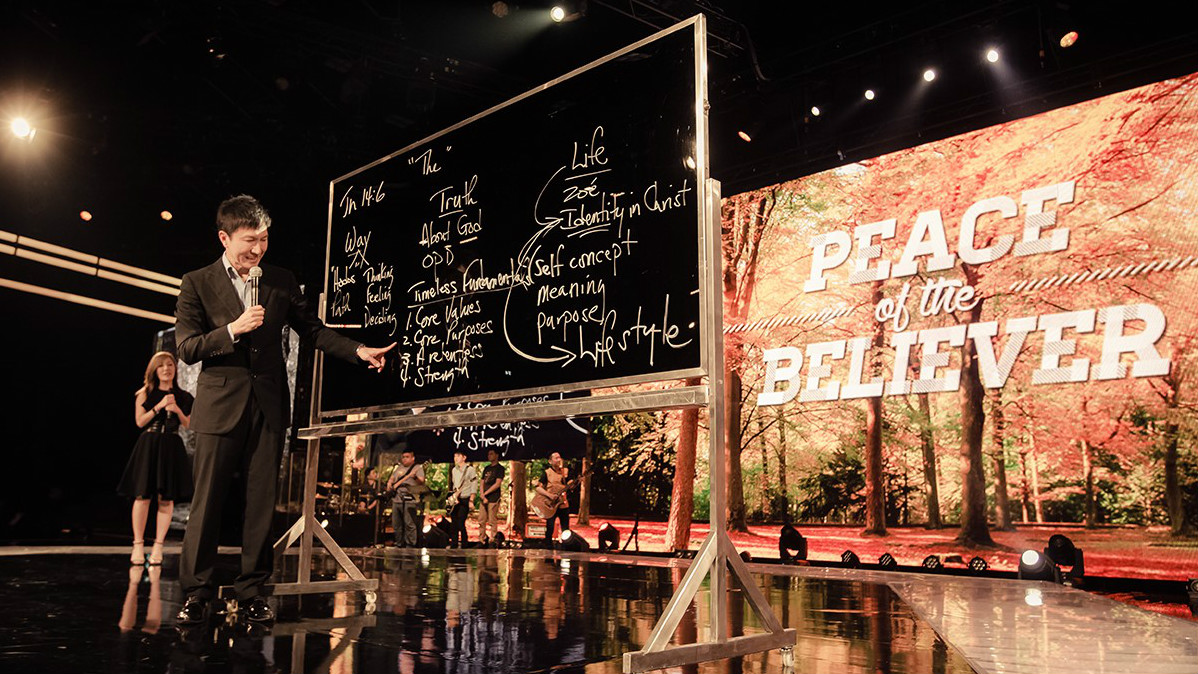

On Sunday, the senior pastor of Singapore's second-largest megachurch bowed three times to his congregation and apologized.

Last week, Kong Hee and five other leaders of his 17,000-member City Harvest Church (CHC) were foundguilty by Singapore's charity commissioner of siphoning $35.9 million in church funds to support the singing career of Kong's wife and church co-founder, Sun Ho, in the United States and Asia. The megachurch maintains that Ho's pop music was intended as a form of outreach to non-Christians.

“[I am] sorry for the pain you all have had to endure under my leadership and watch … but hopefully, that season in the life of our church is in the past,” said Kong, according to CHC.

"As was the case throughout these past three years of court trial, and the earlier two years of investigation, we have placed our faith in God and trust that whatever the outcome, He will use it for our good (Romans 8:28)," Ho told CHC members last week [full statement below].

The trial of the six church pastors, board executives, and accountants lasted 140 days. CHC is Singapore’s second-largest megachurch and preaches a lucrative version of the prosperity gospel. With 50 affiliate churches and 30 associate churches in the region, CHC nets almost 59,000 in total attendance, according to its 2014 annual report.

Ho’s secular music career was launched in 2002 as a “Crossover Project,” meant to reach non-Christians and expand the church. Ho, who was not charged, is still the megachurch's executive director.

But the funding of the Crossover Project wasn’t straightforward, and in 2012, the six leaders were arrested and charged with misusing church building funds to promote Ho’s career. The Commissioner of Charities accused Kong of diverting funds under the guise of contributions to a sister church in Kuala Lumpur, and one witness testified that building funds were used to buy investment bonds in church-owned companies that promoted Ho’s music career. (The BBC offers an assessment.)

The megachurch also purchased $500,000 in unsold albums to boost her ratings before her American debut.

Lawyers for the defendants argued that the funding of Ho’s career was legitimate, since it was a ministry the church had agreed to support.

“In every aspect, we’ve never felt that we’ve done anything unauthorized,” said deputy pastor Tan Ye Peng, who was found guilty of criminal breach of trust, "round-tripping" of church funds, and falsifying of accounts. The CHC congregation doesn’t feel like it has been deceived, he told the court in March, according to AsiaOne.

“Til today, church members come to me and say, ‘Pastor, hang in there,’” he said. “No one says, ‘Pastor, we've been deceived.’"

Ho has five albums in Taiwan, and appeared in a few hip hop albums in the United States beginning in 2003. The Crossover Project was “always about the church” and not about herself, Ho told the court in May, according to The Straits Times.

The judge disagreed.

“Evidence points to a finding that they knew they were acting dishonestly, and I am unable to conclude otherwise,” presiding judge See Kee Onn told a packed courtroom.

“Naturally, we are disappointed by the outcome,” Ho wrote on the church’s website. “Since 2012, we have had a new management and a new Church Board running the operations of the church. Therefore, let’s stay the course with CHC 2.0. God is making us stronger, purer, and more mature as a congregation.”

Kong and his fellow church leaders will be sentenced next month.

A. R. Bernard, founder of the Christian Cultural Center, New York City’s largest evangelical church, said that part of the problem is cultural. Church-sponsored outreach projects—like films or crossover artists performing both religious and secular music—are “strange” in Singapore, he told the Washington Times in February.

Bernard preached on Saturday and Sunday from Proverbs 17:17.

"I can tell you bluntly that the public was waiting to see if this church would collapse," said Bernard. "Guess what? I'm here. You're here. Every tree the Heavenly Father plants, no one can pluck out. You've been faithful, you've been consistent, you're going to reap the harvest."

CT noted when CHC leaders were first arrested and the progression of the trial.

Here is CHC's full statement:

Trial Verdict: A Statement from the Church Leaders

Dear Church Family,

The judge has rendered his decision and, naturally, we are disappointed by the outcome. Nonetheless, I know that Pastor Kong and the rest are studying the judgment intently and will take legal advice from their respective lawyers in the days to come.

As was the case throughout these past three years of court trial, and the earlier two years of investigation, we have placed our faith in God and trust that whatever the outcome, He will use it for our good (Romans 8:28). This protracted season has been extremely difficult, not just for the six, but also for all their families and friends, as well as for our congregation.

In spite of these challenges, City Harvest Church has an unshakeable calling from God. Recently, Pastor Kong has exhorted us to focus on our core values, and serve the purpose of God with greater effectiveness and sustainability. Since 2012, we have had a new management and a new Church Board running the operations of the church. Therefore, let’s stay the course with CHC 2.0. God is making us stronger, purer and more mature as a congregation.

Thank you for your unwavering faithfulness in loving God and loving one another. More than ever before, let’s have a unity that is unbreakable. We are not alone as many of our friends and churches around the world are also interceding fervently for us. God knows the way that we take; when He has tested us, we shall come forth as gold (Job 23:10).

Pastor Kong and I are humbled by the tremendous outpouring of love and support shown to us during this time. We thank you for your prayers. Please continue to pray for Pastor Kong, Pastor Tan, John Lam, Sharon, Serina and Eng Han.

In Christ’s love, for His glory,

Sun Ho

Co-Founder/Executive Director

On behalf of CHC Management Board