The world is full of beautiful geometry.

It’s something we start teaching our youngest children. This daisy is a circle. This dandelion is a sphere. And we repeat it all the way through high school: Honeybees build their hives in hexagons. Solutions to quadratic equations can be graphed as parabolas. Rates of change are found in the slope of lines tangent to a curve.

“God has established nothing without geometrical beauty,” astronomer Johannes Kepler wrote. Before him, planetary orbits were thought to be perfect circles. He discovered that they weren’t—but that they were in fact ellipses, still part of the same wonderful family known as Euclidean geometry, named for the Greek mathematician who wrote Elements around the year 300 B.C.

Kepler, Newton, Leibniz, Descartes, and others looked at the world and found time and time again that the Euclidean model accurately describes all kinds of shapes and events in nature.

Except when it doesn’t.

You don’t have to look hard to notice aspects of nature that clearly don’t fit the Euclidean framework. Rivers, mountains, coastlines, lightning, our circulatory system: Where’s the symmetry and structure? Where’s the order?

The answer, as mathematicians are discovering more and more often, involves fractals: geometric figures that occur in nature, even in seemingly chaotic systems.

But fractals aren’t easy to understand. Benoit Mandelbrot, who coined the term fractal in 1975, summed them up as “beautiful, damn hard, and increasingly useful.”

Repeat. Repeat. Repeat.

Relative to Euclid’s geometry, 1975 might as well have been last Tuesday. Mathematicians agree that we’ve only just begun to scratch the surface of understanding fractal geometry.

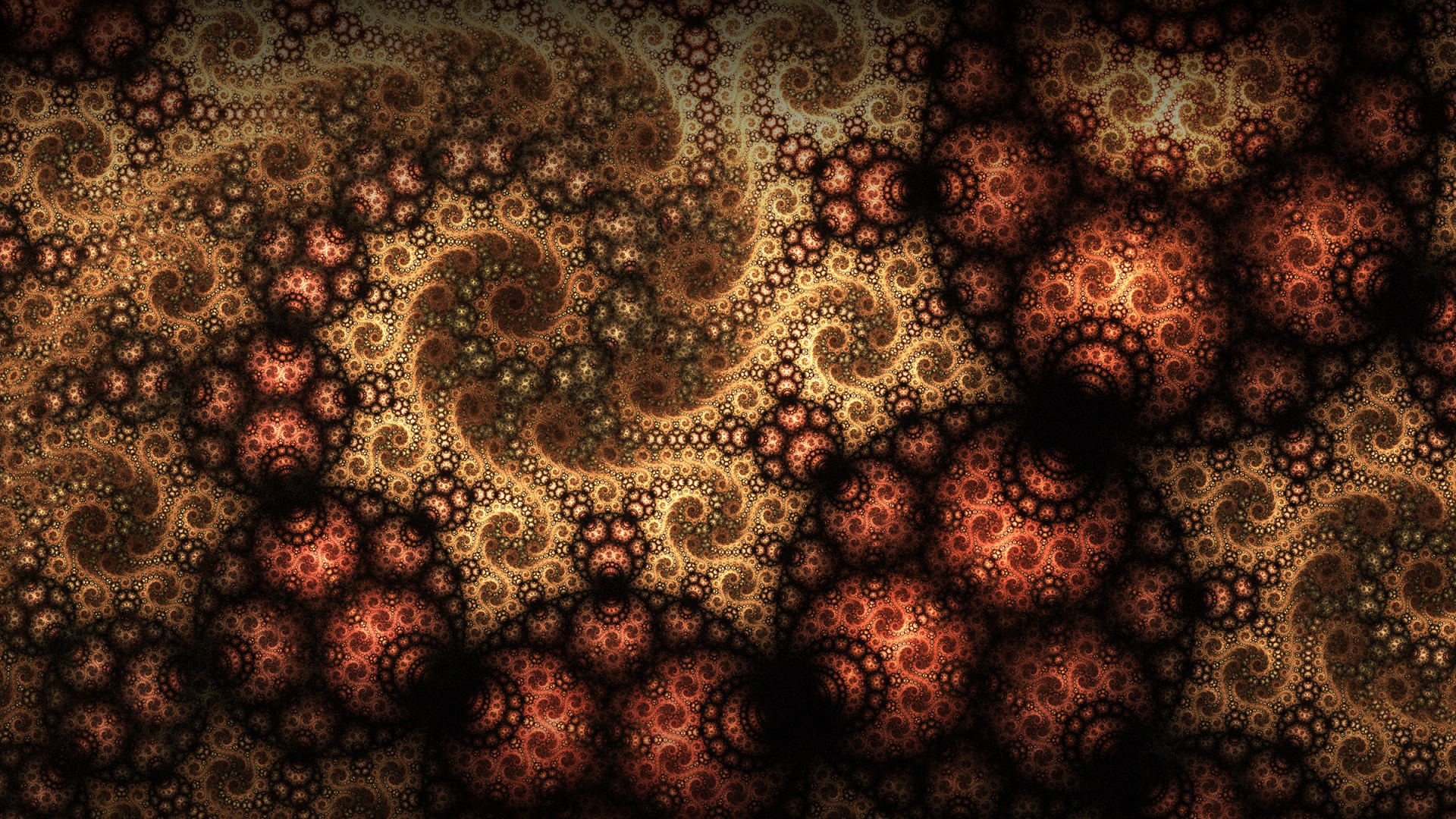

Chances are if you’ve seen a fractal outside of a mathematics classroom, it has been as a psychedelic, swirling image on someone’s computer desktop—something that looks like it could be the background pattern on a Grateful Dead T-shirt.

Some of the earliest fractals came in the late 1800s or early 1900s, well before we had a name for them. These images all followed a simple rule that, when repeated over and over, led (eventually) to an infinitely complex image.

In 1915, for example, Polish mathematician Waclaw Sierpinski described what is now known as Sierpinski’s Gasket. This fractal is made from equilateral triangles repeatedly nested within each other: 1) Start with an equilateral triangle; 2) Divide it into four triangles; 3) Take out the middle one; 4) Divide the three remaining triangles into four triangles; 5) Repeat.

You can imagine that if this pattern is iterated infinitely, then no matter how much you zoom in (or out), it will look the same. In other words, fractals are self-similar: they have the same complexity at every scale.

For a long time, drawings like Sierpinski’s Gasket were just mathematical oddities, curiosities with no significant application (even within the abstruse world of pure mathematics). They were even called “pathological curves.”

‘Look. Look. Look.’

Benoit Mandelbrot brought these mathematical oddities out of obscurity.

Mandelbrot had only a little mathematical training early on in life. (Running to escape the Nazis tends to interrupt one’s formal education.) He was naturally brilliant, though, and passed the university entrance exam in France after World War II with no preparation.

In natural phenomena like cauliflower, mountain ranges, and blood capillaries, Mandelbrot noticed that each individual section looked like the entire phenomenon—but none of it was remotely “Euclidean.” This epiphany inspired him to start looking at Sierpinski’s Gasket and other fractal images. (“When I seek, I look, look, look,” he later wrote in his memoirs.) He read long-forgotten mathematical papers that touched on the concept of infinite geometry; one in particular examined the mathematics of coastlines. And he started plotting solutions to a system of complex algebraic equations known as a “Julia Set.”

The Julia Set of equations are recursive: You plug in a number, evaluate the equation, take the final answer, and plug it back into the original expression over and over again. Mathematicians had already examined the Julia sets, but it took an enormous effort just to run through a few hundred iterations. The answers quickly got so huge that it was unreasonable to find many iterations of any one expression.

By this point in Mandelbrot’s career, he had left the academy and was working for IBM. He put computers to work evaluating the various Julia expressions. In a matter of minutes, his programming had eclipsed the number of iterations ever achieved by hand in the decades before. After just hours of work, the computer had generated millions of iterations of solutions to the Julia equations.

Mandelbrot discovered that when the collected (infinite) solutions to the Julia sets were graphed, they formed an image that was infinitely self-similar. This famous image came to be known as the Mandelbrot Set.

After the debut of the Mandelbrot Set, mathematicians started discovering fractal geometry all over the place. There are systems of complex equations whose solutions lend themselves to predicting river courses, describing the way ice crystals form on your windshield, and illustrating the way our arteries and veins are organized inside our bodies. Some of the early “pathological curves” are now used as wide-band antennas in cell phones, and it’s been proven that a fractal antenna is actually required (not just ideal) to accept as wide a range of frequencies as possible. Mandelbrot himself discovered that the noise in telephone wires could be modeled using Cantor’s Set, a fractal from 100 years earlier. Scientists have even discovered a fractal in the drumming fluctuations in the 1982 Michael McDonald song “I Keep Forgettin.’ ” “Increasingly useful,” indeed!

Deeper than Order

Our temptation as Christians might be to simply observe this information about fractals and take comfort in it: i.e., seemingly chaotic systems actually do have an order, and that, therefore, proves the existence of an intelligent Creator in whom we already have faith!

But you don’t have to be a Christian to be awed by the fractal geometries found in nature. Mandelbrot himself said that plotting Julia Set solutions never felt like invention to him:

I never had the feeling that my imagination was rich enough to invent all those extraordinary things on discovering them. They were there, even though nobody had seen them before. It's marvelous, a very simple formula explains all these very complicated things. So the goal of science is starting with a mess, and explaining it with a simple formula, a kind of dream of science.

The Christian and materialist alike can use the discoveries of fractal geometry to support their worldview. But what if it’s less about proving the existence of a Creator, and more about receiving a gift from him, a revelation about what he is like?

“Fractal geometry is not just a chapter of mathematics,” Mandelbrot said, “but one that helps Everyman to see the same world differently.”

What can we say of a God who creates using both Euclidean geometry—the “ideal” shapes—and fractal geometry?

Could the self-similarity of fractals be a reflection of the reality that “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today, and forever”? Or of Jesus’ claim, “I and the Father are One”? Can a fractal’s infinite geometry perhaps remind us not just of God’s infinite attributes, but also of the gospel mystery of that same, infinite God dwelling in Christians (literally, “little Christs”)? Might it be an image of “Christ in you, the hope of Glory”?

Does the infinite complexity of fractals reflect any similar characteristics of God? If we imagine a God who would have only created the “ideal” shapes of Euclidean geometry, we might view the chaotic features of our world—mountains, coastlines, clouds—as a result of the fall, a consequence of the sin that entered our world. We might be tempted to extend this chaotic ideology onto God himself, and draw some troubling conclusions. Did God lose control of his natural order? Is he letting the universe spiral into chaos and decay?

But when we consider a God who purposefully uses the infinite complexity of fractal geometry, we might instead focus on an intricate plan laid “before the creation of the world” (Eph. 1:4) to rescue a cosmos not yet in need of rescue. I don’t understand the infinitely complex layers of such a plan of salvation, but I can accept that the same complexity God demonstrates throughout creation can be found in his plan for my life. And when I study the amount of complexity in a fractal—zooming in closer and closer, yet never losing any resolution or altering its appearance in any way—I am reminded that the same painstaking detail went into God’s plan for my life. I break out in praise. And then I want to zoom in a bit more.

Joel Bezaire is a teacher and musician from Nashville, Tennessee. His previous article for The Behemoth, “How Infinitely Big Is God?” examined set theory.