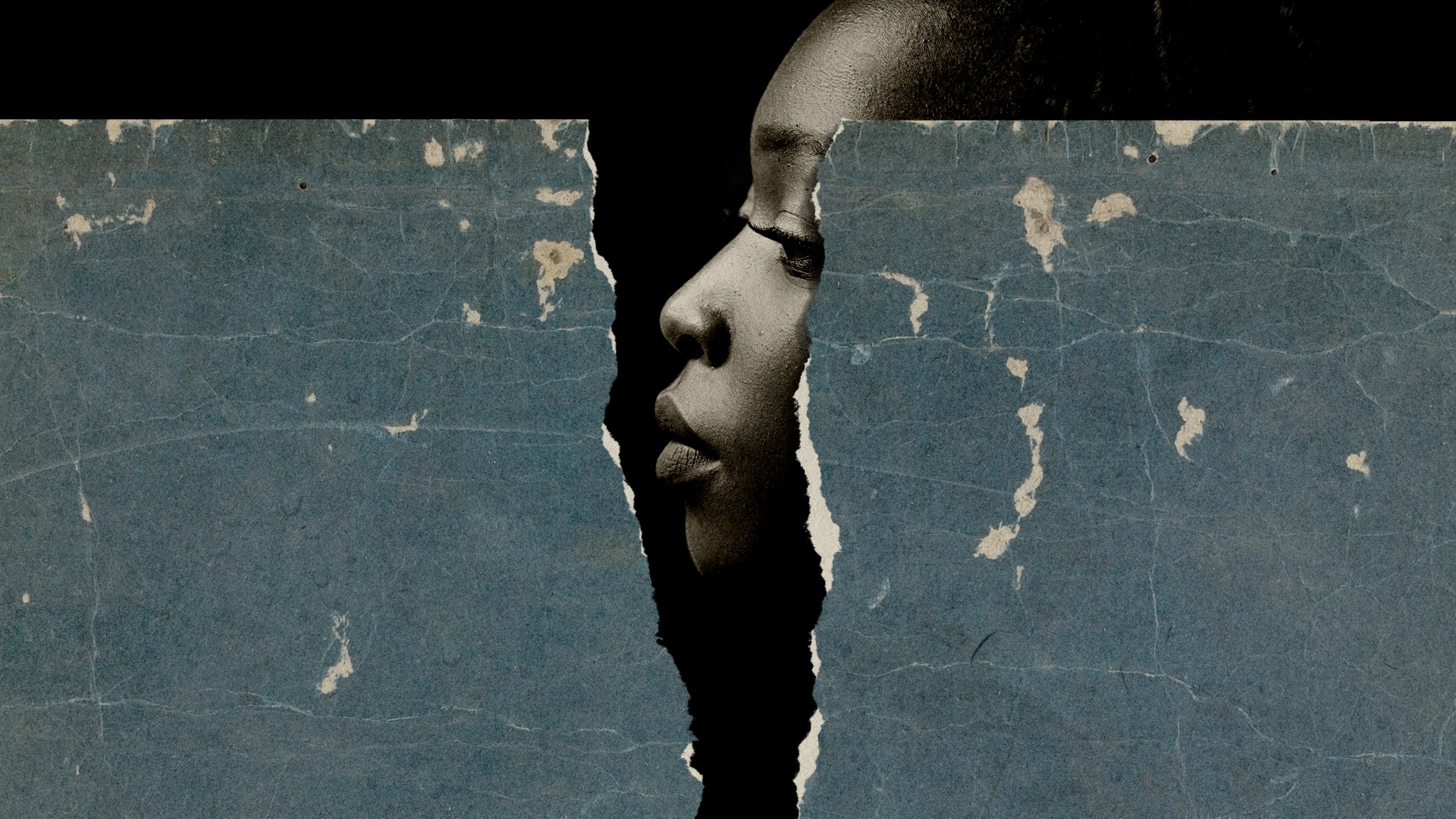

Brenda Kimuli typically worked 16 hours a day.

From her desk inside a walled compound in a mountainous region of Myanmar near the Thailand border, the single mom from Uganda tapped out messages on one of six smartphones. She wrote to lovesick online acquaintances around the world, trying to persuade them to invest in cryptocurrency.

When she succeeded, she directed her contacts to a website that would, unbeknownst to them, funnel their money into accounts belonging to the Chinese criminal organization that employed her.

But one day in March 2024, Kimuli, who had moved across a continent for what she thought was a job at a marketing firm, was not at her desk. She was instead trapped in what she and her coworkers called the “darkroom.”

As punishment for refusing to work, Kimuli sat with one wrist handcuffed above her head—cutting off her circulation—and the other cuffed to the ground. She tried shifting in her chair to get feeling back in her arm as the cuffs dug into her flesh.

For days she remained suspended, deprived of food and drink and forced to soil herself. Sometimes a soldier from a local military group shocked her with an electric baton. When she asked for water, he brought some of his own urine. When she refused to open her mouth, he touched the baton to her cheek and poured the urine down her throat.

It was her fourth time in the darkroom in six months.

“I prayed to God to die,” Kimuli said. “I hated myself so much. I was so tired.”

After three days in the darkroom, she was unable to walk and had lost all feeling in her right hand. Yet she agreed to return to her job in “pig butchering”: a form of cyberscamming named for the way perpetrators butter up targets with trust and love until it’s time for the slaughter—draining the victims’ bank accounts.

“If you rebel again,” Kimuli’s captors told her, “we’ll cut off your hands.”

Kimuli detailed her experiences to me six months later at an immigrant detention center in the Thai border city of Mae Sot. She rubbed her scarred wrists as she recounted how what had first seemed like an “unbelievable career opportunity” had quickly turned into a living hell.

In 2023, the United Nations estimated that at least 120,000 people might be trapped in cyberscamming compounds in Myanmar. An additional 100,000 may be forced to work in similar operations elsewhere in Southeast Asia as actors in fraudulent investment schemes, dating-app fronts, and cryptocurrency hustles.

The complex criminal organizations behind the scams create two different groups of victims: those swindled out of large sums of money after trusting fake online personas, and the real people behind those personas, who are often trafficked and forced against their will to deceive strangers.

Not long after pig butchering began coming into its own around 2020, coalitions of government officials, human rights groups, and Christian organizations—ranging from International Justice Mission (IJM) to Australia-based Global Advance Projects—began working to free enslaved scam workers.

“This is a global threat. It impacts every government on the earth,” said Amy Miller, Southeast Asia regional director of Acts of Mercy International, the relief and development arm of the Texas-based Antioch Movement of churches. “We all need to be in the game. We don’t have the luxury of sitting back and letting the enemy pillage and destroy.”

But combatting cyberfraud groups is not as simple as raising awareness. Asian authorities are often less than sympathetic toward escaped labor-trafficking victims, struggling to distinguish between those who were lured unwittingly and those who knowingly joined in criminal activities.

Cybercrime syndicates are also adept at eluding the law. Human rights advocates say the groups have powerful allies in local governments. And when authorities do crack down on illegal online businesses, as the Philippines did in the mid 2010s, the organizations move into countries with weaker or fractured governments.

None has been as promising a destination for criminal groups as conflict-stricken Myanmar.

Satellite image ©2023 Maxar Technologies.

Satellite image ©2023 Maxar Technologies.I traveled to the Thailand-Myanmar border to see how antitrafficking groups there are faring. In Cambodia, where I used to live, forced scamming is a well-known menace.

The large-scale trafficking of unsuspecting foreigners into cyberscamming started in Cambodia during the COVID-19 pandemic. The global shutdown emptied Chinese-owned casinos located in special economic zones meant to attract Chinese investment. Those vacant casinos and hotels, already hotbeds of illegal activity before the pandemic, presented opportunities for Chinese criminal groups to innovate.

The syndicates, some of which had dabbled in pig-butchering schemes, began aggressively posting fraudulent job listings online. They lured in applicants, often from other parts of Southeast Asia. Once job candidates arrived in Cambodia, operatives seized their passports and electronic devices, locked them in hotels, and forced them in front of screens to begin scamming.

Workers were told that if they made a certain amount of money, they could earn back their freedom. As Kimuli experienced, disobedience often resulted in beatings and torture.

The scams initially targeted Chinese citizens. But as the criminal groups acquired foreign workers fluent in more languages, the scammers broadened their efforts and began snaring victims around the world.

Andrew Wasuwongse, IJM’s director in Thailand, called forced scamming a “humanitarian crisis” that has rapidly spread across Southeast Asia. “This is the fastest-growing form of modern-day slavery in the world,” he said.

The amounts of money involved are also enormous. Based on testimony IJM has collected from victims and witnesses in Cambodia, Wasuwongse said, a scammer can bring in $300 to $400 per day. Experts estimate that scamming revenues in Cambodia alone exceed $12 billion annually—the same amount American shoppers spent during Cyber Monday in 2023. Interpol said in early 2024 that Southeast Asia’s scamming industry brings in about $3 trillion a year.

Investigating and prosecuting cybertrafficking cases is not always straightforward. Forced-scamming workers do not all fit the popular profile of trafficking victims. Some are well educated, are well traveled, and speak multiple languages. Some have degrees in IT or engineering.

“Some people coming out of the compounds are not victims,” Wasuwongse said. “While many are completely trafficked and clueless about what they are getting into, some are in the middle. Those in the middle knew they would be committing fraud and scams, but they did not realize they would then be forced.”

In early 2021, Wasuwongse’s colleagues in Cambodia started tracking media reports about foreign workers forced to conduct scams in large, heavily guarded compounds there. They began receiving calls from these victims in April 2021, recording testimonies and compiling supporting evidence. They provided information to local law enforcement offices to help them pursue the most compelling cases and free victims. When victims made it out, IJM helped them file reports with their nations’ embassies.

So far, Wasuwongse said IJM has helped more than 100 individuals escape scam compounds in Cambodia, and nearly 400 across Southeast Asia.

Cambodian authorities began cracking down in August 2022. Since then, they say they have rescued more than 2,000 foreigners, shut down 5 companies, and arrested 95 people. Yet the illicit industry continues there, and powerful actors at the top operate with impunity. To date, the Cambodian government has not arrested, prosecuted, or convicted a single business owner accused of connections to forced scamming, despite wide-scale reporting on the crime, Wasuwongse said.

To evade accountability, many cyber-fraud organizations have moved their operations to Myanmar. Ongoing civil war there has left much of the borderland near Thailand, Laos, and China outside government control.

In mid-2022, IJM and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) noticed reports of people escaping these Myanmar compounds and arriving in the Thai border city of Mae Sot or in Bangkok. In immigration detention centers, some people accused of overstaying their visas were claiming to be victims of forced scamming.

Around that same time, Judah Tana, the founder of Global Advance Projects, a Christian group fighting child exploitation, was in Mae Sot, watching construction crews erect massive, mysterious compounds across the Moei River in Myanmar’s Kayin State.

One evening, Tana had a friend over who pointed out a surprising message on a Mae Sot Facebook group she monitored. A Kenyan woman was asking about visas and saying she had been trafficked into Thailand.

“Initially, we thought it was a scam,” Tana said. He messaged her with questions about her situation and how she had gotten to Thailand. Then his wife came across a tweet from the Kenyan government warning about cyberscam compounds.

Tana reached out to the Kenyan embassy in Bangkok. He kept communicating with the Kenyan woman and learned she was one of seven Kenyans in the same situation who were begging for help. As he reached out to different people in Thai law enforcement, the government, and foreign embassies, it seemed as if no one had a clue what was happening in the compounds.

Through his previous human rights work with refugees, immigrant children, and former child soldiers, Tana had developed connections with Myanmar’s ethnic-minority resistance groups, which hold sway in much of the country’s border regions. He contacted some of their leaders and asked for help freeing the Kenyans. They agreed to speak with the Chinese bosses of the local scam compounds.

In October 2022, the seven Kenyans were released. From then on, others trapped in the compounds began calling Tana from smuggled phones.

Tana and other like-minded groups formed a small coalition to focus their efforts on bringing workers out of the compounds. Miller, the Acts of Mercy director, soon relocated from Cambodia to Thailand to be closer to the border compounds.

One of them was where Kimuli was trapped.

Before coming to Thailand, Kimuli worked at a fast-food restaurant in Dubai, sending money to her parents in Uganda to pay for her son’s schooling.

In an interview with CT, she recounted how she had been trafficked and enslaved 3,000 miles from there.

In 2023, a friend at work told her about a promising marketing job in Bangkok with better hours and pay. Kimuli loved Thai television and thought living in Bangkok would be fun. Her coworker connected her with a recruiter named Joanna; soon Kimuli and her friend joined several others to meet the recruiter in Dubai.

The job-seekers asked questions about the position description, benefits, and hiring process. Joanna confidently answered each one. The company, Young An, required basic typing speeds and computer skills and promised on-the-job training. Joanna showed videos of staff sharing positive testimonies about their work environment. Impressed, Kimuli applied and was accepted after a round of interviews.

Kimuli and other hires were told to enter Thailand on tourist visas that would soon be converted to work visas, a process that is legal in Thailand. In September 2023, Kimuli and four others landed in Bangkok. A company driver met them at the airport to take them to their hotel.

Things quickly took a dark turn. The driver gestured for them to give him their passports. They grew nervous as the drive stretched into two hours. When they tried to ask questions, the driver said, “No English.” No one had a local phone, so they couldn’t call anyone.

When the driver stopped for gas and snacks, they found themselves locked in the vehicle. During the night, they passed several roadblocks guarded by armed soldiers.

“I cried out to God and prayed,” Kimuli said. “I thought I was going to die.”

The driver stopped in what seemed like the middle of nowhere, and a van arrived. They were forced into the new vehicle, which sped off into the dark. Then, at a river, an armed group of men loaded their luggage into a boat and told them to get in.

Eventually they arrived at the gates of a guarded compound. Soldiers took their phones and searched their luggage.

“I couldn’t think straight at this point,” Kimuli said. “I was so overwhelmed with fear and exhaustion. All of us women were locked in a room to sleep. I knew this was a dangerous place.”

After about three hours of sleep, a Chinese boss woke them. A Burmese man translated as the boss explained what their daily routine would be at the compound.

All of the bosses were Chinese, Kimuli said, but the soldiers who guarded the compound were from Myanmar—consistent with a UN report which found that “border guard forces under the authority of the Myanmar military or its proxies” provide protection for scam operations. Such arrangements help fund armed groups, Tana said.

Kimuli’s translator took her to another room, where she soon realized she and the other kidnapped foreigners would be scamming people. A boss gave her six phones, a long list of phone numbers, and a script to follow as she messaged people. When the scam victims asked to video-chat or see photos of Kimuli, the bosses would bring in models, who she learned were also held against their will.

To build trust with their marks, Kimuli and others often tried to forge romantic connections. They created Tinder profiles. Some told CT that if their dating-app profiles were reported as suspicious and shut down, bosses had them create X accounts and befriend supporters of President-elect Donald Trump. Using a script, they would discuss politics, then introduce victims to cryptocurrency investments or asking them to donate to fake right-wing causes.

Kimuli and her coworkers told CT they were forced to work 16 to 20 hours a day. They described conditions similar to what other trafficking victims have shared with media and human rights groups.

“There would be severe punishments if we took too long to answer the person we were scamming,” Kimuli recalled. “I couldn’t leave my keyboard.”

If she was slow or fell asleep, her captor would cane her or hold an electric cattle prod to her leg. The first time she was punished for responding too slowly, a guard beat the back of her legs so severely it was painful to sit for two weeks.

The worst punishment, however, was the darkroom.

When Kimuli lost a client she had been building a relationship with, her captors took her to the darkroom, handcuffed her, and hung her by her arms from an overhead pipe. Soldiers kicked, caned, and electrocuted her if she cried or fell asleep. They sprayed her face with water until she thought she would suffocate. She heard the screams from others also being tortured. Sometimes the Chinese bosses came in to help the soldiers.

One day in December, Kimuli and 20 other Ugandans refused to work and demanded their captors send them home. About 100 armed soldiers were called in to haul the protestors to the darkroom, where Kimuli said they were tortured and denied food or water for three days.

After that, Kimuli and a few others were moved to another compound. This location was similar, although now Kimuli was scamming Turkish and Pakistani citizens on Facebook and TikTok. Once she had reeled in a victim, a Chinese worker would take over to close the financial component of the scam.

About five months into this work, a boss told Kimuli to pack her bags: She was going home. But instead of going to the airport, she was brought back to the first compound. She was told, “I bought you. … I spent too much money on you. You need to work a long time to pay for this.”

Kimuli felt her resolve fade.

“I just laid down and gave up,” she said. That’s when she was taken to the darkroom for the fourth time.

Other rescued workers told CT they were made to do hundreds of squats in the hot sun for not meeting their quotas. They said their bosses withheld food if they underperformed. They were tortured for complaining about conditions or for making mistakes with their English.

One survivor took off his shirt to show his chest and back, covered in scars and bruises from canings and electrocution; some wounds were still healing. Like Kimuli, his arms and wrists also bore marks from handcuffs.

While Kimuli was living in her nightmare, government officials were working to free her. A few of the Ugandans had hidden phones; Kimuli used one to call home and was also put in touch with Tana and Miller. Around December, another Ugandan contacted Betty Oyella Bigombe, Uganda’s ambassador to several countries in Southeast Asia.

Appalled at what she heard, Bigombe began taking calls from the trapped Ugandans day and night, encouraging them to remain strong as she tried to do something. Bigombe had experience in dealmaking: In the 1990s and early 2000s, she was the chief negotiator during peace talks with Joseph Kony, the leader of the militant Lord’s Resistance Army rebel group.

Eventually, Bigombe was connected with Miller and Tana. Then she contacted the Border Guard Forces (BGF), a Myanmar militant group that controls the region where the compounds are located. Through the BGF, she negotiated with the crime bosses, who initially asked for a ransom of $10,000 per person, which Bigombe said she refused to pay.

On Easter weekend in 2024, the bosses woke Kimuli and 22 other Ugandans early. She said they forced some of the workers to record videos saying they’d had a good experience with the company; everyone was made to sign confessions that they had taken the job willingly and were treated well.

Then they were driven to a bridge at the Moei River, Thailand on the other side.

Kimuli realized she was truly being released when she spotted Tana and Miller on the Thai shore.

The Ugandans set foot in Thailand three months after their first phone call to Bigombe, who rushed to greet them in Mae Sot.

“There is no way this story would have happened without Jesus,” Miller said. “The ambassador was on her knees praying for them for months. We were constantly praying.”

In February 2024, while reporting for this story, I got a call from a friend named Heidi Boyd who lives in the northwestern United States.

As we caught up, I asked Heidi how her dating life was going. She is in her 40s and had been finding it difficult to meet single men her age. She had tried the dating app Bumble but was disappointed with the few dates she went on.

Heidi told me she was about to quit Bumble in 2023 when a man named Sim connected with her there. He was drawn to her profile, he had said, because she described herself as someone who was drawn to people who helped others.

Sim and Heidi began talking daily. Heidi had been to China several times, and Sim was a Hong Kong national who said he lived in Los Angeles, a city she had previously lived in. His profile and information checked out. He told her he was in Hong Kong taking care of his sick father, so it might be a while until they could meet in person.

Eventually, they felt it was time to become exclusive, and they moved their conversations off Bumble and onto WhatsApp. They chatted on video only a few times, as their time zones were difficult to navigate.

About three months into their deepening relationship, they began planning to travel the world together and serve others.

Around this time, Sim shared that he’d had some success in cryptocurrency investing. Heidi, who considers herself savvy about investing, grew interested. She thought the money she earned through trading could go to support global ministries.

“I am aware of my privilege and how I have a responsibility to help people with my resources,” Heidi said. She showed me screenshots of their chats. “I wanted to give away money to people who needed it.”

Sim recommended a crypto investment app. Heidi investigated the crypto platform and its website; they seemed legitimate. She downloaded it to her phone and began putting in funds. Some days she earned money, and other days she lost it. She could withdraw funds whenever she wanted to.

There were occasional hiccups when she tried to transfer money from her bank into her investment account. But Sim told her that that was normal, because big banks did not want to lose their customers.

Over the next few months, her investment grew. When it hit $150,000, the crypto platform suddenly flagged her account as suspicious, notifying her that it needed further proof of her identity. The platform imposed a new restriction: She couldn’t withdraw her funds unless she put down a 20 percent deposit.

Heidi borrowed money from her mother to make the deposit. She told me she was a day away from paying it when her sister sent her an article about something called pig butchering.

Heidi read the article and realized that she was living it.

“I think I’m being scammed,” she told me on the phone. She was slowly coming to recognize that Sim had been part of the scam.

Heidi told me she wanted to write him and tell him how horrible a person he was.

I suggested that Sim might be a victim himself—that in fact he might have been multiple people, some of whom could have been enslaved by criminal groups.

“I am 50 percent heartbroken over losing a relationship that felt real,” Heidi told me later. “I thought I had a future with someone. I shared so much of my life with them over five months. The other part of me is hurt because I lost my retirement.”

Both betrayals wounded her and caused incredible shame. She agreed to share her story, she said, because she hoped bringing that shame into the light would deprive it of its power—and also because of the possibility that her shame is shared by someone on the other side of the world.

“I feel mobilized to pray,” Heidi said. “God has given me such an assurance of his love and that he loves all of the trafficked people. God loves the Chinese crime lords. I’ve been praying for their hearts to be changed.”

Stories like Kimuli’s—where an entire group of workers is freed with the help of government officials—are inspiring. They are also rare.

More often, victims are released because they paid a ransom, or because they met their quota, or because they’re poor performers.

“Normally, they know they are coming out,” said Miller of Acts of Mercy. “They communicate, and we go pick them up. They’ve been through trauma; they need time to breathe and be given some choices or to walk around and experience freedom.”

When trapped workers do contact the outside world for help, it can take months of communication to coordinate a release—at great risk to the worker.

Occasionally, in dramatic instances, a victim will contact Tana and Miller and say they’re being moved or sold to another compound. Victims have alerted Tana and Miller to their location and then jumped from moving vehicles to escape.

Such approaches are dangerous: Victims flee without bags and passports and can suffer injuries.

“I’m not stupid or naive of the risks,” Tana said. “But I love Jesus so much, and I think, He would do it.”

Yet escaping compounds is only the beginning of what can be arduous journeys home.

Trafficked scam workers who were brought first to Thailand are often trapped in Myanmar as their visas expire. If they manage to get back to Thailand, they do so under a cloud of suspicion—having overstayed their visa, misplaced their passport, and engaged in criminal activities.

In such situations, freed workers can turn themselves in to Thai immigration and pay a 4,000 baht ($110 USD) fine. After a few days in jail, they’ll be sent to a detention center until they can find money to purchase a ticket home.

“The immigration detention center is a difficult place to be,” Miller said. “They get almost no food, and conditions can be worse than the compounds.”

Another option is to go through the National Referral Mechanism, an international program for recognizing victims of human trafficking and providing them housing and other assistance. Thai officials interview victims to vet their claims and gather evidence that could one day be used to prosecute labor traffickers.

All 23 Ugandans opted to try for government recognition as trafficking victims, with Bigombe at their side. On April 11, 2024, after two days of interviews, all 23 were granted it.

They were fortunate. Miller said only about 10 percent of applicants to the program receive recognition. “We try to help them know what the process will be like and what questions will be asked. But the government has its own burden of proof and what makes a victim a victim. It’s not always clear.”

Satellite image ©2023 Maxar Technologies.

Satellite image ©2023 Maxar Technologies.Miller and Tana’s organization, as well as other Christian human rights groups, are pushing for greater global awareness of the uphill battle trafficking victims face even after they secure their freedom.

“There are still too many closed-door meetings about things, and only heads of state or major players get invited … so there is no information out to the layman,” Tana said. “The body of Christ globally needs to get the word out on this.”

Scam center workers return home traumatized, unable to talk about their experiences. Many are Muslim or Christian and feel deep shame for what they have done.

“What I did was haram,” one young Muslim man from South Asia told me soon after fleeing a compound, referring to practices forbidden by Islamic law. “My family can never know.”

At one point, he said, his captors offered him a prostitute for his good work, which he refused.

Miller and Tana say that Muslims who were forced to scam have told them that if people knew what they did, they would be forced to commit suicide out of shame.

While combatting trafficking is a favorite cause of evangelicals in the United States and other wealthy nations, antitrafficking ministries say that churches in Africa and Asia also have important roles to play.

For starters, they can raise awareness among the populations that are most susceptible to labor trafficking. One Ugandan victim told me he would like to see the church provide more education and skills training to keep people employed in their communities, making them less likely to chase misleading opportunities abroad.

Antitrafficking groups also want to see more churches become safe places for former scam workers to talk about their guilt and trauma. One of Miller and Tana’s goals is to create a global database of churches that provide counseling, aftercare, and employment services for repatriated forced scammers.

“They need church and NGO [nongovernmental organization] leaders to listen and understand where they are coming from,” Miller said. “Healing happens in presence and being with people in their suffering. Jesus is present with us in our suffering.”

Even after the Ugandans were officially recognized as trafficking victims, Kimuli remained in a government shelter in Mae Sot for another two months.

There was paperwork to process. There were the slow-moving logistics of securing UN funds for food, legal fees, shelter, and plane tickets. And there was a growing number of escaped workers like Kimuli across Southeast Asia, all taxing the small humanitarian programs trying to help them.

On May 23, the Ugandans finally boarded a plane to go home. Kimuli was dreaming of a simple meal of cassava and tea at her family’s kitchen table.

During that long wait, Kimuli thought a lot about God’s provision.

She had first answered the ad for the job in Asia because she had a son to provide for and she wanted to do more for him than she could with her fast-food job in Dubai.

But God was already looking after him.

While Kimuli was trapped for seven months in forced labor, she learned later that her son’s school had given him a scholarship to cover his tuition and food. “I disappeared, and God still took care of my son,” she said.

Money, it turned out, had conned everyone in that Myanmar compound: her bosses, her online victims—even herself.

“I was enticed by money,” Kimuli said. “God has shown me that money is not everything. I now know God can give me everything I need. I am going home with nothing but trusting God.”

Erin Foley lives in Thailand and works in communications for refugee and orphan-care ministries.