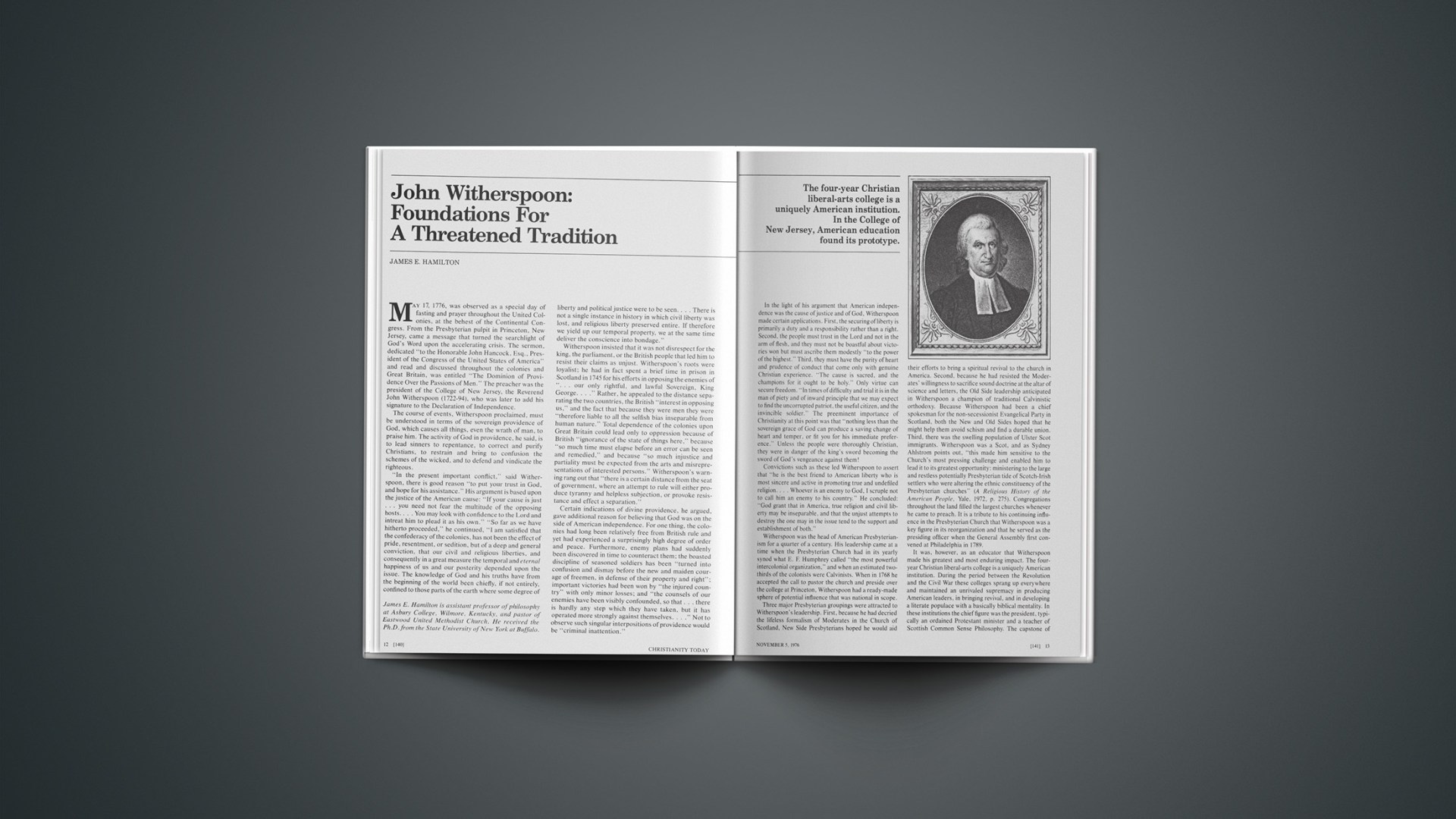

May 17, 1776, was observed as a special day of fasting and prayer throughout the United Colonies, at the behest of the Continental Congress. From the Presbyterian pulpit in Princeton, New Jersey, came a message that turned the searchlight of God’s Word upon the accelerating crisis. The sermon, dedicated “to the Honorable John Hancock, Esq., President of the Congress of the United States of America” and read and discussed throughout the colonies and Great Britain, was entitled “The Dominion of Providence Over the Passions of Men.” The preacher was the president of the College of New Jersey, the Reverend John Witherspoon (1722–94), who was later to add his signature to the Declaration of Independence.

The course of events, Witherspoon proclaimed, must be understood in terms of the sovereign providence of God, which causes all things, even the wrath of man, to praise him. The activity of God in providence, he said, is to lead sinners to repentance, to correct and purify Christians, to restrain and bring to confusion the schemes of the wicked, and to defend and vindicate the righteous.

“In the present important conflict,” said Witherspoon, there is good reason “to put your trust in God, and hope for his assistance.” His argument is based upon the justice of the American cause: “If your cause is just … you need not fear the multitude of the opposing hosts.… You may look with confidence to the Lord and intreat him to plead it as his own.” “So far as we have hitherto proceeded,” he continued, “I am satisfied that the confederacy of the colonies, has not been the effect of pride, resentment, or sedition, but of a deep and general conviction, that our civil and religious liberties, and consequently in a great measure the temporal and eternal happiness of us and our posterity depended upon the issue. The knowledge of God and his truths have from the beginning of the world been chiefly, if not entirely, confined to those parts of the earth where some degree of liberty and political justice were to be seen.… There is not a single instance in history in which civil liberty was lost, and religious liberty preserved entire. If therefore we yield up our temporal property, we at the same time deliver the conscience into bondage.”

Witherspoon insisted that it was not disrespect for the king, the parliament, or the British people that led him to resist their claims as unjust. Witherspoon’s roots were loyalist; he had in fact spent a brief time in prison in Scotland in 1745 for his efforts in opposing the enemies of “… our only rightful, and lawful Sovereign, King George.…” Rather, he appealed to the distance separating the two countries, the British “interest in opposing us,” and the fact that because they were men they were “therefore liable to all the selfish bias inseparable from human nature.” Total dependence of the colonies upon Great Britain could lead only to oppression because of British “ignorance of the state of things here,” because “so much time must elapse before an error can be seen and remedied,” and because “so much injustice and partiality must be expected from the arts and misrepresentations of interested persons.” Witherspoon’s warning rang out that “there is a certain distance from the seat of government, where an attempt to rule will either produce tyranny and helpless subjection, or provoke resistance and effect a separation.”

Certain indications of divine providence, he argued, gave additional reason for believing that God was on the side of American independence. For one thing, the colonies had long been relatively free from British rule and yet had experienced a surprisingly high degree of order and peace. Furthermore, enemy plans had suddenly been discovered in time to counteract them; the boasted discipline of seasoned soldiers has been “turned into confusion and dismay before the new and maiden courage of freemen, in defense of their property and right”; important victories had been won by “the injured country” with only minor losses; and “the counsels of our enemies have been visibly confounded, so that … there is hardly any step which they have taken, but it has operated more strongly against themselves.…” Not to observe such singular interpositions of providence would be “criminal inattention.”

In the light of his argument that American independence was the cause of justice and of God, Witherspoon made certain applications. First, the securing of liberty is primarily a duty and a responsibility rather than a right. Second, the people must trust in the Lord and not in the arm of flesh, and they must not be boastful about victories won but must ascribe them modestly “to the power of the highest.” Third, they must have the purity of heart and prudence of conduct that come only with genuine Christian experience. “The cause is sacred, and the champions for it ought to be holy.” Only virtue can secure freedom. “In times of difficulty and trial it is in the man of piety and of inward principle that we may expect to find the uncorrupted patriot, the useful citizen, and the invincible soldier.” The preeminent importance of Christianity at this point was that “nothing less than the sovereign grace of God can produce a saving change of heart and temper, or fit you for his immediate preference.” Unless the people were thoroughly Christian, they were in danger of the king’s sword becoming the sword of God’s vengeance against them!

Convictions such as these led Witherspoon to assert that “he is the best friend to American liberty who is most sincere and active in promoting true and undefiled religion.… Whoever is an enemy to God, I scruple not to call him an enemy to his country.” He concluded: “God grant that in America, true religion and civil liberty may be inseparable, and that the unjust attempts to destroy the one may in the issue tend to the support and establishment of both.”

Witherspoon was the head of American Presbyterianism for a quarter of a century. His leadership came at a time when the Presbyterian Church had in its yearly synod what E. F. Humphrey called “the most powerful intercolonial organization,” and when an estimated two-thirds of the colonists were Calvinists. When in 1768 he accepted the call to pastor the church and preside over the college at Princeton, Witherspoon had a ready-made sphere of potential influence that was national in scope.

Three major Presbyterian groupings were attracted to Witherspoon’s leadership. First, because he had decried the lifeless formalism of Moderates in the Church of Scotland, New Side Presbyterians hoped he would aid their efforts to bring a spiritual revival to the church in America. Second, because he had resisted the Moderates’ willingness to sacrifice sound doctrine at the altar of science and letters, the Old Side leadership anticipated in Witherspoon a champion of traditional Calvinistic orthodoxy. Because Witherspoon had been a chief spokesman for the non-secessionist Evangelical Party in Scotland, both the New and Old Sides hoped that he might help them avoid schism and find a durable union. Third, there was the swelling population of Ulster Scot immigrants. Witherspoon was a Scot, and as Sydney Ahlstrom points out, “this made him sensitive to the Church’s most pressing challenge and enabled him to lead it to its greatest opportunity: ministering to the large and restless potentially Presbyterian tide of Scotch-Irish settlers who were altering the ethnic constituency of the Presbyterian churches” (A Religious History of the American People, Yale, 1972, p. 275). Congregations throughout the land filled the largest churches whenever he came to preach. It is a tribute to his continuing influence in the Presbyterian Church that Witherspoon was a key figure in its reorganization and that he served as the presiding officer when the General Assembly first convened at Philadelphia in 1789.

It was, however, as an educator that Witherspoon made his greatest and most enduring impact. The four-year Christian liberal-arts college is a uniquely American institution. During the period between the Revolution and the Civil War these colleges sprang up everywhere and maintained an unrivaled supremacy in producing American leaders, in bringing revival, and in developing a literate populace with a basically biblical mentality. In these institutions the chief figure was the president, typically an ordained Protestant minister and a teacher of Scottish Common Sense Philosophy. The capstone of the curriculum was often a course in moral philosophy taught by the president. In the College of New Jersey and in its president, John Witherspoon, this future pattern of American education found its prototype.

When Witherspoon came to the College of New Jersey (later to become Princeton University) he set out to strengthen and enrich the broad liberal-arts base on which it had been founded. To do this, he purchased for the library more than three hundred books on theological, philosophical, educational, and political subjects; he expanded the curriculum by adding French and broadening the courses in Hebrew, theology, and philosophy; he introduced the lecture method of teaching; and he purchased the famous Rittenhouse orrery, a mechanical model of the solar system, which led to a professorship in mathematics and natural philosophy in 1771 and which inspired a fair amount of significant political philosophizing.

The essence of Witherspoon’s contribution to American higher education was in the area of ideals, in the vision of an educational system that would produce consecrated Christian students who had an integrated and thoroughly biblical world view and also a burning desire to find a place of useful service. Spiritual matters received top priority in his philosophy of education. “Religion,” he said, “is the grand concern to us all, as we are men;—whatever be our calling and profession, the salvation of our souls is the one thing needful” (Works [1803 edition], IV, 11). Literature without piety, he maintained, “is pernicious to others, and ruinous to the possessor.” However, piety without literature “is but little profitable.” Therefore, Witherspoon told his students, “The great and leading view which you ought to have in your studies, and which I desire to have still before my eyes in teaching … may be expressed in one sentence—to unite together piety and literature—to show their relation to, and their influence upon one another—and to guard against anything that may tend to separate them, and set them in opposition” (Works, IV, 10).

Witherspoon regarded Scripture as divine revelation but held that the Bible was not intended to teach us everything. Academic studies are most fruitful when investigation of biblical truth proceeds in conjunction with research into the various areas of God’s creation. He himself was initially uncertain whether to teach in the area of divinity or elsewhere. He ended up doing both.

It has been said that Witherspoon was more interested in producing secular leaders than in producing ministers. This contention is falsified by his own words as well as by the large number of his students who entered the ministry. “Nothing would give me a higher pleasure,” he asserted, “than being instrumental in furnishing the minds, and improving the talents of those who may hereafter be the ministers of the everlasting gospel” (IV, 10).

Perhaps Witherspoon’s greatest gift to American thought and education was his introduction and fervent propagation of the method, epistemology, metaphysics, and ethics of Thomas Reid’s Common Sense Realism. Following Reid, Witherspoon argued that the human mind can and does know truth and that the ordinary experience of universal humanity carries its own self-evident authentication. The proper method of special investigation in any area is the inductive approach advocated by Francis Bacon, which should be applied to the study of man as well as the material world. The senses are the appropriate instruments for the knowledge of physical realities, while inward self-consciousness is the primary source of knowledge of the psyche. Even in the area of metaphysics Witherspoon thought it safer to trace facts upward than to make deductions downward.

The tenets of Scottish or Common Sense Realism included an ontological dualism between the world and God, a psychological dualism between soul and body, the rationality and objectivity of moral judgments, and a real though limited freedom of the human will. Witherspoon regarded the freedom of the will as vindicated by conscious experience and as necessary for understanding the biblical doctrines of human responsibility and guilt. He was never able to reconcile his thinking at this point with the theology of John Knox, but he took this to be a failure in his own understanding and continued to contend for both.

The significance of Witherspoon’s introduction of the philosophy of the Scottish Enlightenment to the American scene cannot be overestimated. Common Sense Realism became for a century the most universal force shaping the American mind and was the chief instrument for integrating knowledge in Christian liberal-arts colleges during the years of their growing importance in American life. Its widespread acceptance was a major reason why revivalistic Christianity was so widely embraced, particularly by thinking people. Its teaching on the freedom of the will had a moderating influence on Calvinistic theology and greatly strengthened the case for liberty in the political realm.

The extent of Witherspoon’s influence as president and professor at Princeton was furthered by the intercolonial character of the college and by the subsequent careers of his students. Among the American colleges of Witherspoon’s day, only Princeton was intercolonial. Part of the reason for this was its non-denominational status. Though established and largely directed by Presbyterians, it was free of official church control and open to students of all denominations without discrimination. The primary reason, however, was the widespread geographical distribution of Ulster Scot settlers, hence of Presbyterian churches and people, throughout the colonies. As William W. Sweet points out, “Harvard, Yale and the College of William and Mary were largely local institutions, drawing their students from the colonies in which they were located, which was likewise true to a large extent of King’s College in New York and the College of Philadelphia.… When James Madison entered the College of New Jersey, of the eighty-four students in attendance only nineteen were from New Jersey, and every colony was represented in the student body. Of the twelve students who were in the graduating class of 1771 only one was from New Jersey” (Religion on the American Frontier, Harper, 1936, II, 7). In 1776 roughly one-fourth of the alumni of the College of New Jersey were from New England, one half from the middle colonies, and one fourth from the South.

Great men in history, Witherspoon told his students, have generally appeared in clusters. He urged them, therefore, to maintain their friendships after graduation. Witherspoon purposed to produce leadership for strategic areas of national life. His students pervaded the pulpit ministry, education, and government. No fewer than 114 became clergymen. At least ten colleges and academies were founded by former students. Foremost educational institutions in Pennsylvania, Virginia, North and South Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Georgia had men who had studied with Witherspoon or one of his students in places of leadership. Thirteen of his pupils became college presidents.

Among the Princetonians in the national government with Witherspoon’s signature on their diplomas were President James Madison (“Father of the Constitution”), Vice-president Aaron Burr, ten cabinet officers, six members of the Continental Congress, twenty-one senators, thirty-nine representatives, three Supreme Court judges, one attorney general. There were also twelve state governors. Although these figures involve some overlapping, still they only begin to indicate the amount of public service rendered in the young republic by students of John Witherspoon. As a Christian gentleman, a pastor, an educator, and a statesman, he lived what he taught.

Witherspoon’s role as a statesman was hardly less significant than his roles as a churchman and an educator. Within two years of his arrival in America, he had met the Madisons, the Lees, the Washingtons, and other prominent families and had established himself as a national figure. A member of the Continental Congress, he also sat on more than a hundred committees between the Revolution and the Constitutional Convention. For several months in 1783 the Continental Congress actually took up residence in Princeton’s Nassau Hall. John Adams called him an “animated son of liberty.” Horace Walpole is said to have informed Parliament after the Declaration of Independence that the Americans had “run off with a Presbyterian parson.” Sweet writes that “no patriotic leader in the colonies had been more influential or useful to the cause of independence than John Witherspoon” (Religion on the American Frontier, II, 5). Jonathan Odell, the powerful Tory satirist, was less complimentary:

… Unhappy New Jersey mourns her thrall,

Ordained by the vilest of the vile to fall;

To fall by Witherspoon!—O name, the curse

Of sound religion, and disgrace of verse.

Member of Congress, we must hail him next:

‘Come out of Babylon,’ was now his text.

… I’ve known him seek the dungeon dark as night,

Imprisoned Tories to convert, or fright;

Whilst to myself I’ve hummed, in dismal tune,

I’d rather be a dog than Witherspoon

[Moses C. Tyler, ed., The Literary History of the American Revolution, 1897, II, 122].

We must take note also of Witherspoon’s activities as a pamphleteer and as a man of prayer. His prodigious literary efforts began amid the storms of church controversy in Scotland and came to maturity in the American political crisis. Though he wrote on religious and educational topics also, the majority of his essays in this country were on matters of political concern. His most masterly piece was probably his “Essay on Money as a Medium of Commerce, with Remarks on the Advantages and Disadvantages of Paper admitted into General Circulation.” As a member of the congressional committee on finance, Witherspoon had jeopardized his popularity by opposing the use of paper currency in the years immediately after the war. His essay was later published at the insistence of some of the very congressmen who had originally resisted his views. His conception of a sound financial policy for the United States therefore precedes that of Alexander Hamilton.

Witherspoon gave daily priority to personal and family devotions. On the last day of each year he and his family customarily observed a day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer; he also set aside other days for personal fasting and prayer, as it seemed appropriate.

The American Revolution, according to Moses Coit Tyler, “was preeminently a revolution caused by ideas and pivoted on ideas.” It may be that when all the facts are in, Witherspoon’s greatest significance will be found in the fact that at the time of our nation’s founding he was the chief spokesman for the great tradition of biblical faith that has been the soul of Western civilization as well as of American culture, a tradition that bequeathed to the world such concepts as limited government and the separation of political and religious spheres of authority.