For the last 100 years, conversation around the Virgin Birth has centered on whether it actually happened. Could Mary really have had a child without a previous sexual union? Maybe, the thinking went, ancient people were simply more gullible in the face of stories like these.

While the historicity of the Virgin Birth is an important question, there are others worth asking. In his new book Conceived by the Holy Spirit: The Virgin Birth in Scripture and Theology, Rhyne Putman analyzes some of the most pivotal: Did the Virgin Birth need to happen? What if it hadn’t? And why does it matter today?

Not a lot of books exist on this topic from an evangelical perspective. But Putman, a professor at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, has provided a helpful overview.

In part 1, Putnam carefully examines the birth narratives of Jesus in the Gospels. Throughout this section, he responds to various objections critics have raised. Some have claimed, for instance, that the notion of the Virgin Birth came from pagan mythology. Some have posited that Mary’s place in the narrative of Jesus’ birth describes a metaphorical rather than a biological reality. Other challenges to the biblical accounts ask whether God violated Mary’s sovereignty, or whether the Virgin Birth contradicts the church’s belief that Jesus existed as God’s eternally begotten Son before his incarnation.

In part 2, Putnam discusses the theological meaning and implications of the Virgin Birth. Here, he puts this doctrine into conversation with others, considering how it bears on subjects like Creation, the Trinity, the person and work of Christ, his status as the Second Adam, and his second coming. Putnam closes with two appendices: one that proposes a “harmony” of the biblical nativity stories and another that evaluates traditional Catholic beliefs about Mary.

My favorite parts of the book concern the significance of the Virgin Birth. Putman argues that it was fitting for Jesus to come to earth in this way even if it wasn’t absolutely necessary.

There are three reasons for this. First, the Virgin Birth is fitting because it reveals that Jesus is truly human as well as truly divine. Usually, when we think of the Virgin Birth, we emphasize the improbability of a virgin giving birth while downplaying the birth itself. However, treasures reside in both terms. The Virgin Birth is certainly amazing because Jesus was born of a virgin, but it’s equally amazing that God himself was born.

Early Christian heresies denied that Jesus was born. The Docetists, for instance, taught that Jesus was only a spirit being. The church responded by affirming that Jesus was truly and fully human and was born like any other human (except for the virgin part). Jesus took his flesh from Mary, and thus he could truly thirst, be tempted, and suffer. The second person of the Trinity descended from David and was born according to his flesh.

Second, the Virgin Birth is fitting because it signals Jesus’ uniqueness. It indicates that Jesus, though fully human, is unlike every other human being. He is naturally the Son of God but adopted a human father for himself in Joseph. The Virgin Birth displays Jesus, in the words of the Nicene Creed, as “God from God, Light from Light.”

Jesus’ existence did not begin when human sperm fertilized a human egg. In fact, Jesus did not ever begin to exist, since he has existed from before the creation of the world (John 1:1–3; Col. 1:15–17). The Virgin Birth bears witness to the fact that Jesus’ life didn’t begin at conception like ours.

Third, the Virgin Birth is fitting because it signals that we are saved by grace alone. Jesus’ coming was not the result of human ingenuity or the forethought of Israel. Like Mary and Joseph, we are simply recipients of God’s favor and grace. It was God’s action that caused Jesus to be born, not the grand plan of humanity. This reminds us that our salvation is based on God’s initiative. We didn’t orchestrate our salvation; it was wrought by God.

If the Virgin Birth is fitting in all these ways, then what we celebrate at Christmas is not simply an interesting factoid we can marvel at until the novelty wears off. Nor is it something that should cause embarrassment. Rather, the Virgin Birth contains the story of salvation. This miraculous event signals who Jesus is and how he will save us. It touches, then, on core Christian convictions.

I can’t think of many comprehensive books on the Virgin Birth, and Putnam’s volume is a wonderful resource to help people think more carefully about this essential event. (Amy Peeler’s book Women and the Gender of God touches on some of the same subjects, but her focus is narrower.)

Still, there are two aspects of Conceived by the Holy Spirit that I would alter. Putnam spends more time on the scriptural interpretation of the Virgin Birth (249 pages) than on the theology it communicates (92 pages). I think he should have flipped this ratio, or perhaps integrated these subjects more naturally. There are plenty of good biblical commentaries that walk readers through the narratives of Christ’s incarnation; not as many present a comprehensive theology of the Virgin Birth.

Additionally, by separating biblical interpretation from theology, Putman risks furthering the flawed impression that these are separate subjects. I’m convinced that biblical scholars and theologians alike should exemplify how the work of interpreting Scripture includes theological judgment as a matter of course.

Additionally, I think Putnam could have devoted more than an appendix to Marian dogmas within Catholicism. His discussion is quite brief, leaving little room to unpack the most controversial Catholic claims regarding her immaculate conception (the belief that she was born apart from Original Sin), her perpetual virginity, her bodily assumption to heaven immediately after death, her intercession before God, and her presence in various icons.

For example, Putman might have interacted with a recent contribution to Marian theology by Brant Pitre, Jesus and the Jewish Roots of Mary: Unveiling the Mother of the Messiah, which attempts to ground the Catholic position in typological arguments from Scripture. Such engagement might fall outside the scope of the book as Putman envisioned it. But I think readers would benefit from added attention to Marian points of division between Catholics and Protestants.

Ultimately, Putnam aims to encourage our faith, especially during Advent season, by having us carefully consider the Virgin Birth. Contrary to popular misconceptions, having faith doesn’t mean believing that which is opposed to evidence. Faith seeks out evidence.

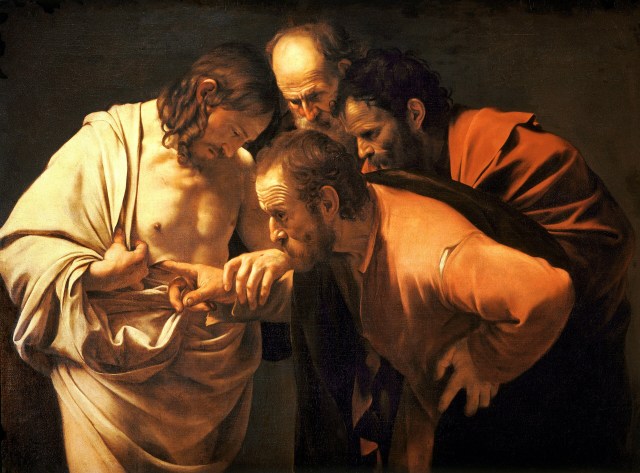

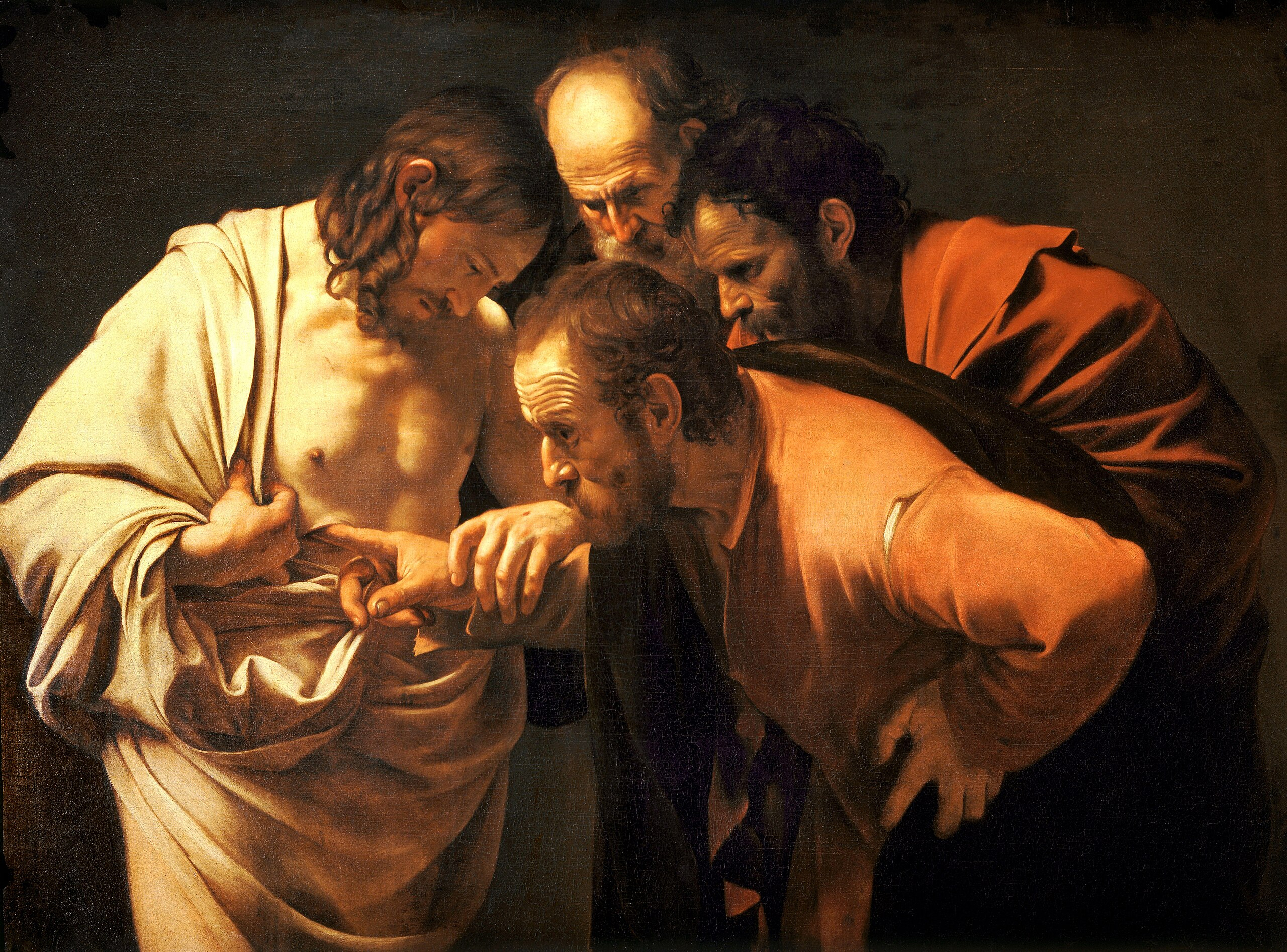

If you carefully examine the scriptural texts on events like the Virgin Birth or even the Resurrection, you’ll notice that ancient people also had a hard time admitting such things could happen. Mary asks questions of the angel who announced she would give birth to Jesus. Joseph assumes Mary’s infidelity until an angel sets him straight. Thomas doubts the truth of Jesus’ resurrection until he sees and touches his wounds. Ancient people affirmed natural laws, but they could be convinced of realities beyond nature.

Faith, then, allows us to open ourselves up to what might initially seem unbelievable. As theologian Geerhardus Vos once wrote in his classic study Biblical Theology, “Religious belief exists not in last analysis on what we can prove, but on the fact of God having declared it to be so.”

Abraham believed in his old age that he would become the father of many nations. His hope in God enabled him to believe this “against all hope” (Rom. 4:18). We must believe, like Abraham, that God can do what seems beyond belief. When we celebrate Christmas, we celebrate God’s supernatural power not only to enter our world as a child but also to bring new life to those under death’s curse.

Patrick Schreiner is associate professor of New Testament and biblical theology at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. He is the author of The Transfiguration of Christ: An Exegetical and Theological Reading.